Political risk is once again dominating boardroom agendas as trade tensions, wars and populism reshape the global landscape. From the return of Donald Trump to the White House to renewed instability across the Middle East and Africa, the forces driving uncertainty in 2025 have tested companies’ resilience and insurers’ capacity like never before. Maria Gonçalves reports.

The political shocks that have disrupted global supply chains over the past five years “won’t abate in 2025”, insurance broker WTW warned early this year – a prediction that now looks understated.

Since then, Donald Trump’s comeback has reignited trade disputes, the Middle East conflict has escalated despite a US-brokered peace deal, and tensions continued to simmer from Ukraine to the Red Sea, as well as between India and Pakistan and China and Taiwan.

Reflecting this volatility, Coface’s 2025 social and political risk index reached a historic high of 41.1%, surpassing its pandemic-era peak and cementing political risk as a “key structural parameter of the global economy”.

Companies are increasingly concerned. WTW’s annual political risk survey in May found that political instability ranked among the top five risks on the enterprise risk management register for 74% of multinational companies. For 11% of respondents, it was the number one concern.

“Geopolitics is no longer an area of just academic or passing interest,” says Nick Marro, lead analyst for global trade at the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU).

“We’re very much in unprecedented times – 10 years ago, you could do business largely without worrying about international security hot spots, or volatility posed by electoral cycles or government shifts. That’s no longer the case.”

Insurers, for their part, are acutely aware of the growing threat. Axa and Ipsos’ Future Risks Report 2025, published in October, found that risk experts now rank global geopolitical instability as the second most significant danger.

Alongside entrenched trade and supply chain disruption, the report also highlights regional conflicts, cross-border cyber-attacks and the spread of misinformation.

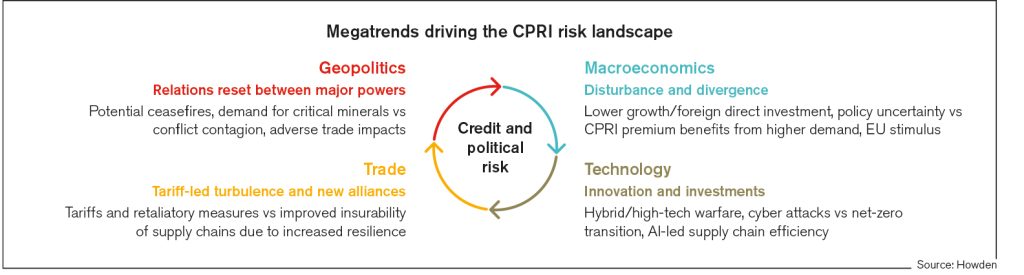

Geopolitical instability is also becoming more intertwined with other major risks, it said, including climate change, energy security and access to natural resources.

Claims, demand and capacity

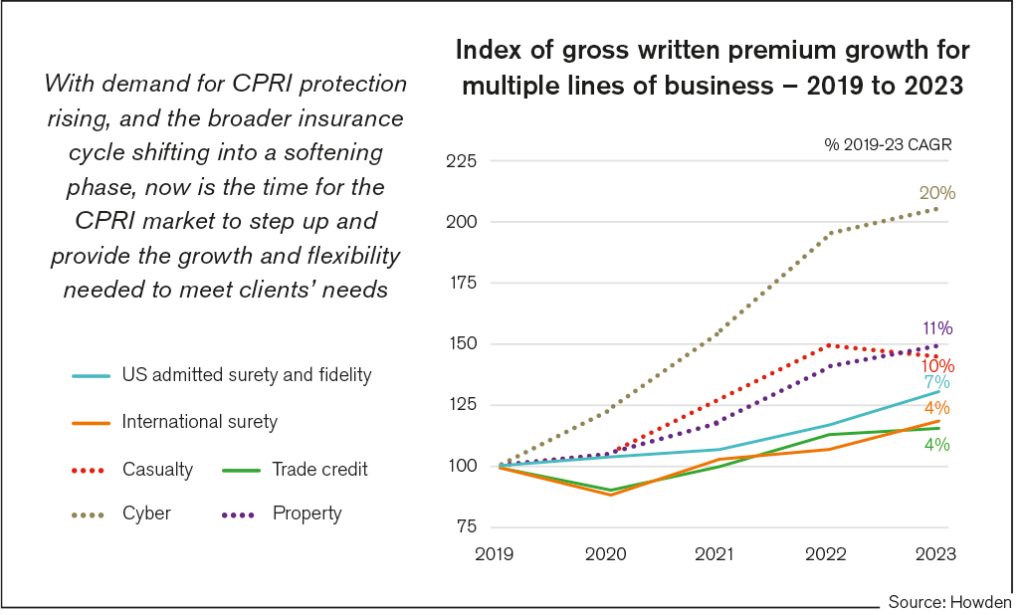

As risks multiply and exposures deepen, demand for insurance protection is inevitably rising, with the growing appetite for political risk cover now reflected in the data.

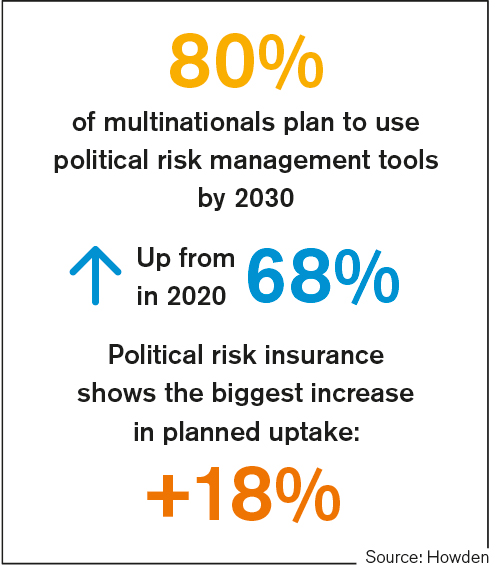

A September 2025 report by Howden found that 80% of multinational companies plan to use political risk management tools over the next five years, up from 68% in 2020.

Political risk insurance showed the largest increase in planned uptake, at 18%, as companies seek greater protection for overseas investments and projects.

“The need for political risk cover is being driven by the increasingly uncertain geopolitical outlook and escalating tensions between the leading powers,” says Elizabeth Stephens, managing director at Geopolitical Risk Advisory.

“Given the deteriorating risk environment, the potential for an event to spark a cascade of claims across the market, which has a systemic impact, cannot be discounted.”

Some of the most common political risk claims in 2025 have included “public arrest, some supply chain and trade disruption risks, and forced abandonment – which is a non-physical damage business interruption type of risk because there’s a threat to life as a result of political violence”, says Andrew van den Born, global head of credit and political risk insurance (CPRI) at WTW. The latter will see “increased claims going forward”, he believes.

To accommodate this increased demand, capacity in the structured credit and political risk market has expanded, with “more insurers capable of writing long-term risks than ever before”, according to Gallagher Speciality’s Q1 2025 report.

Broker Gallagher estimates that market capacity for political risks and contract frustration now stands at around US$3.5bn per risk, as insurers become more willing to take on longer tenors and more challenging jurisdictions.

Even so, political risk insurance capacity still faces chronic constraints compared to other lines, such as property or cyber, notes Sarah Taylor, head of political risks and structured credit at Aon.

“The Russia-Ukraine conflict, Middle East instability and increased frequency of large claims have made insurers more cautious, leading to tighter terms and broader reserving in political risk markets,” she says.

Ongoing geopolitical frictions and the shift in economic and foreign policy since Trump’s return to the White House are “certain” to continue influencing trade and investment opportunities, Gallagher’s report warns.

Political risk insurers are therefore “closely monitoring exposures and may reduce maximum line sizes or adjust terms in response to global events, making capacity more selective and potentially less available”, Taylor says.

Looking ahead

As insurers grow more selective, the broader outlook remains clouded by unpredictability. Going into 2026, global trade still “faces significant challenges, with protectionist measures and geopolitical tensions creating a complex economic landscape”, notes the EIU’s Marro.

The full effects of the US’ protectionist approach to trade are yet to materialise, according to the World Trade Organization, while hopes of reduced friction on a global level have been tempered by the EU’s decision to raise tariffs on steel imports and Trump’s shifting stance towards countries like Canada, Russia and China.

Meanwhile, the Middle East faces profound economic repercussions from the Israel-Hamas conflict, and uncertainty persists over whether tensions between China and Taiwan could escalate – a development that would significantly affect the global chip trade.

“In the past, you had isolated instances that were region specific – like the Latin American debt crisis and the Russian financial crisis – whereas now, [risk] is coming from every direction, and you simply can’t predict where it’s going to come from,” says van den Born. “That’s the whole thing about political risks – they’re inherently difficult to predict, and that is a concern.”

Global trade war

Why it matters: Escalating tensions between major economies are disrupting supply chains and prompting tariff measures.

Implications for CPRI: Higher likelihood of contract defaults, trade delays and export credit claims.

With Trump’s second term came a wave of new economic and trade policies that shook up global supply chains and forced businesses to rapidly rethink their trade relationships, logistics routes and investment strategies.

According to WTW’s political risk survey published in May, nearly 60% of organisations expect trade conflicts under the Trump administration to have a negative impact on their finances.

While the shift towards US policy as a driver of political risk is not entirely new – as far back as 2021, the US appeared on WTW’s list of countries where companies experienced political risk losses – the dynamic this time is different and is “resulting largely from President Trump’s aggressive trade actions”, the broker notes.

“The US has become a lot more unpredictable with Trump’s return,” the EIU’s Marro agrees, with Washington-Beijing trade relations remaining particularly fraught.

The trade war between the world’s two largest economies has not only disrupted global supply chains and increased operating costs, but has also “triggered embargos on the export of products, chips and rare earths that are essential to manufacturing and defence”, Stephens notes.

Such restrictions can have serious implications. Past Chinese embargoes on rare earths, for example, have caused delays and shortages across the value chain, even leading to temporary production halts in the automotive sector, according to a McKinsey report in October.

And while China-US conversations are not entirely sour – Trump lowered tariffs on Chinese goods and declared an end to the “rare earths roadblock” after meeting with President Xi Jinping at the end of October – the risk of another sudden escalation in the trade war still “looms large over the horizon”, Marro warns.

“Given the deteriorating risk environment, the potential for an event to spark a cascade of claims across the market, which has a systemic impact, cannot be discounted.”

Elizabeth Stephens, Geopolitical Risk Advisory

Regional conflicts

Why it matters: Ongoing wars in Ukraine and the Middle East threaten investment security and global trade routes.

Implications for CPRI: Elevated sovereign and political risk; insurers may limit exposure or increase premiums in high-risk zones.

The geopolitical instability in trade is “being compounded by the increase in military action by global and regional powers”, says Stephens at Geopolitical Risk Advisory.

In Europe, “the war in Ukraine continues to undermine stability on the continent and has increased the costs of industrial production”, she says, as Russia’s invasion disrupts global energy and agricultural markets.

The US’ involvement with Trump at the helm is further fuelling uncertainty, with his shifting stance on the conflict reflecting volatile relations with both President Volodymyr Zelensky and President Vladimir Putin.

Protection of overseas investment in Ukraine has largely been supported by export credit agencies and development finance institutions, including Denmark’s Export and Investment Fund, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development and the US International Development Finance Corporation (DFC). In June 2024, the DFC announced a programme providing more than US$350mn in political and war risk insurance for Ukraine. Under the current US administration, however, the future of US institutional support remains uncertain.

Similarly, in the Middle East, the “breakdown of international norms and rules of engagement is injecting ways of uncertainty into all trading and investment strategies”, Stephens says.

She highlights the Israeli bomb attack that targeted Hamas leadership reportedly housed in a Qatari government residential complex in September, which “further unsettled the region, as an attack on a major US ally had not been factored into most risk calculations”.

Ukraine and the Middle East are not the only flashpoints. WTW’s van den Born warns that one of the biggest concerns for the political risk insurance market is the threat of potential military conflict between China and Taiwan.

If escalated, this could result in another chokepoint for global shipping.

The Taiwan Strait is a conduit for more than a fifth of global seaborne trade, with Taiwan also producing over 90% of the world’s advanced semiconductors – critical components in everything from smartphones to military equipment and data centres.

“No one is looking to take on new exposure in China at the moment – the majority of insurers are actually seeking to reduce their exposure to China,” van den Born says.

Another layer of political risk complexity stems from the “further internationalisation of civil conflict”, argues James Wilson, departmental head of special risks at Tokio Marine Kiln, “whereby third-party countries become involved in domestic conflicts to further their own aims”.

This, he says, raises the risk of a wider spillover as they “drag in an increasing number of participants, both covertly and openly”.

Financial market volatility and sovereign debt risks

Why it matters: Rising global debt and warnings from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) about “disorderly” market corrections could trigger sovereign defaults or economic crises.

Implications for CPRI: Companies face a higher risk of counterparty default and political interference in capital flows.

Financial volatility has emerged as a key source of political risk, as rising global debt, market corrections and sovereign defaults heighten uncertainty for companies operating across borders.

The IMF warned in mid-October that overvalued asset prices and widening government deficits could trigger a “disorderly” global market correction.

In its Global Financial Stability Report, the IMF said these risks are exacerbated by “close ties between banks and less-regulated financial firms” as well as trade tensions and high US tariffs, which are now creating the first signs of pressure on employment, activity and inflation.

Coface’s October forecasts point to global growth of only 2.6% in 2025 and 2.4% in 2026, with sluggish eurozone expansion and a slowing China contributing to persistent uncertainty.

Broker and risk adviser Aon has also identified economic slowdown as the third-largest risk globally.

“Beneath the calm surface, the ground is shifting in several parts of the financial system, giving rise to vulnerabilities,” the IMF noted in its report.

The global lender warned that central banks must stay vigilant to inflationary pressures stemming from new trade tariffs and proceed carefully with any monetary easing to avoid fuelling asset price surges. It also urged governments to implement swift fiscal reforms to rein in deficits and strengthen bond market stability.

In Africa and parts of Asia, WTW’s van den Born warns “there continues to be a high level of unsustainable debt”, with defaults in countries like Sri Lanka, Zambia and Ghana in recent years having “resulted in claims in the market”.

Increasingly stressed sovereign balance sheets “leave little fiscal headroom for many economies to weather unforeseen events, from natural catastrophe to economic downturns”, explains Tokio Marine Kiln’s Wilson.

He lists the “accelerated decoupling of the global economic order and increasingly multi-polar landscape, with competing power centres and rising isolationism” as a top political risk.

The EIU’s Marro agrees that over-reliance on single markets, partly driven by a growth in the “isolationism” trend, intensifies exposure for global businesses.

This could lead to a rise in firms seeking protection against sovereign default, counterparty risk and market instability.

Cyber threats

Why it matters: State-sponsored cyberattacks, digital infrastructure disruption and ransomware attacks are now central to geopolitical tension.

Implications for CPRI: Cyberattacks are a source of political risk claims, especially for cross-border investments and critical infrastructure projects.

Cyber risk has firmly entered the political risk arena, as digital attacks increasingly blur the line between criminal activity and acts of geopolitical aggression.

Insurers are well aware of the threat. According to Aon’s 2025 Global Risk Management Survey, cyberattacks or data breaches rank as the number one business risk worldwide, driven by AI-enabled phishing, ransomware and deepfake attacks.

Additionally, Axa’s Future Risks Report found 95% of experts now believe the world faces “multiple crises”, with one of the top concerns being technological threats such as cyberattacks.

“In cyberspace, the line between criminal and state-sponsored activity is becoming increasingly blurred,” warns Stephens, and with it “the risk of a miscalculation that escalates into large-scale conflict”.

Axa’s Future Risks Report found 95% of experts now believe the world faces “multiple crises”, with one of the top concerns being technological threats such as cyberattacks.

However, WTW’s van den Born points out that attribution – the process of tracking and identifying the perpetrator of a cyberattack – remains the biggest challenge.

“To ascertain whether [an attack is] state-sponsored or not is quite difficult to do,” he cautions. “You might have actors working on behalf of the state, but to say it’s been state-sanctioned is very difficult to prove.”

Grey-zone attacks are also increasing, Stephens says, citing incidents such as undersea cable cuts and coordinated ransomware campaigns against energy and logistics infrastructure – actions that “pose a risk to the economic and national security of a significant number of countries”.

Howden’s report also confirmed there has been “a notable increase in hybrid warfare activity, with hostile states targeting critical infrastructure… whilst also exploiting social media for propaganda purposes”.

This evolving threat landscape means cyber and hybrid warfare are now material drivers of potential cross-border political risk claims, particularly in infrastructure and trade supply chains.

Additionally, the rise of AI could impact opportunities for youth employment in many emerging economies, notes Wilson, with both migration and domestic unrest a “growing threat”.

“Increasing youth unemployment in an age of technological change and disinformation has started many movements over the last 20 years,” he warns.

Such intertwined threats reflect an urgent need for risk capacity that bridges technology and sovereignty exposures, as insurers and investors alike navigate an environment where cyber risk sits at the intersection of digital, political and financial vulnerabilities.