January 2019 was a landmark month for the European Union’s fight against financial crime. Every member state was required to write the 5th Anti-Money Laundering Directive, or 5AMLD, into national law by January 10, bringing in tighter controls around cross-border transactions, customer due diligence and outsourcing. John Basquill examines what impact the new rules will have on the trade finance sector.

Every licensed bank across the EU is subject to the bloc’s rules on financial crime. Designed to stop criminals moving the proceeds of crime through the financial system and to prevent terrorist groups from obtaining financing, the regime effectively positions regulated companies – including banks and other financial institutions – as gatekeepers.

Banks are expected to analyse their customer relationships and behaviour, and to report any potentially suspicious activity to the relevant authorities. Fines for non-compliance can run into the billions of dollars.

The scale of illicit financial activity is staggering. Though near-impossible to measure, the UN estimates the amount of money that is laundered through the financial system each year to total anywhere between US$800bn and US$3tn.

Within the trade sector data is even harder to track down, but open account trade – where transactions are handled but not financed by a bank – has been identified by US-based watchdogs as a “primary vulnerability” for illicit funds. Around 80% of international trade processed through financial institutions is believed to be open account trade.

For institutions offering trade finance, one of the most significant changes brought about by the 5th Anti-Money Laundering Directive (5AMLD) is tougher rules on transactions linked to high-risk countries that have been blacklisted by the EU. However, several other parts of the new directive are also likely to have an impact – in some cases, a positive one. GTR speaks to lawyers specialising in trade finance about what banks need to do to stay on the right side of the law, and where there are still unanswered questions.

Transactions involving high-risk countries

Under 5AMLD, financial institutions are not prohibited from handling a transaction linked to a country deemed high-risk. However, they must carry out extensive additional checks on the end customer and the transaction itself.

Johannes Wirtz, a senior associate at Bird & Bird’s banking and finance practice in Frankfurt, explains: “Trade finance lenders will have to obtain additional information on the customer and on the beneficial owner, on the intended nature of the business relationship, on the source of funds and source of wealth of the customer and of the beneficial owner, as well as on the reasons for the intended or performed transactions.

“In addition, they will need the approval of senior management for establishing or continuing the business relationship and to conduct enhanced monitoring of the business relationship by increasing the number and timing of controls applied, and selecting patterns of transactions that need further examination.”

The demand for greater scrutiny over high-risk international transactions is not new for banks in the EU. Enhanced due diligence was also a requirement in the fourth directive, and legally binding guidelines setting out how it should be carried out have been in place since March 2018.

The language around high-risk countries has changed slightly in 5AMLD, however. Simon Cook, a trade and export finance partner at law firm Sullivan in London, points out that early versions required enhanced due diligence depending where the entity involved is “established”.

“In practice, that essentially meant a company located and/or operating there or an individual residing and/or operating there or being a citizen of a high-risk country,” he tells GTR. “That has now been changed to a business relationship that is ‘involved with’ a high-risk country – but it’s not clear exactly what is meant by ‘involved’ as the legislation is silent on this.”

The lawyer gives the example of an entity operating in a country not considered high-risk, but that happens to do business with a supplier in a high-risk country. He says: “To what extent does that matter, particularly for instance if that supplier does not have anything to do with that transaction? The lack of a definition could potentially cause some issues.

“Another example could be if an individual is a dual national with, say, both UK and Iranian citizenship. Would a transaction involving them require enhanced due diligence? Banks would hope not given the relevant individual has UK nationality, but it’s not clear yet how that is going to work.”

EU blacklist dispute rumbles on

Another issue for financial firms has arisen from a dispute between the European Commission and the European Council over which countries are considered high risk in terms of money laundering.

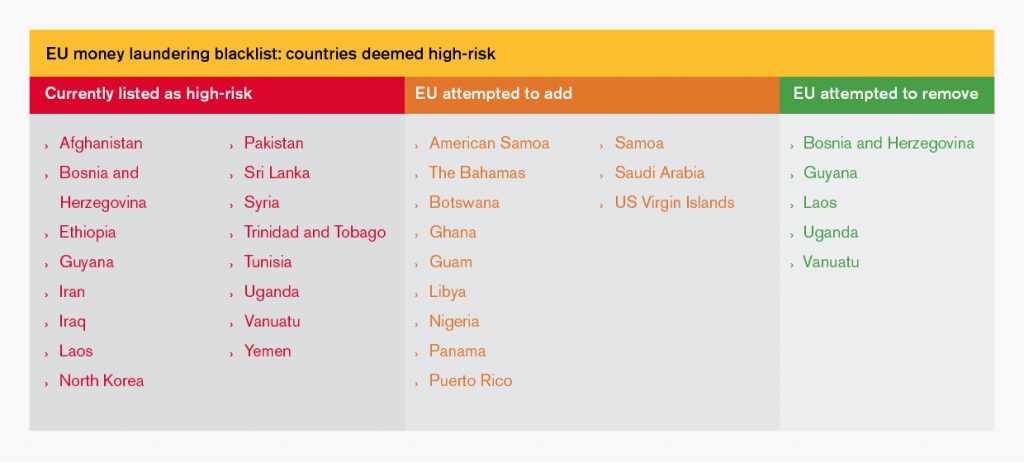

The first European Commission blacklist was produced in July 2016 and amended regularly over the following two years. The current list – still legally binding across the EU – includes Afghanistan, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Ethiopia, Guyana, Iran, Iraq, Laos, North Korea, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Syria, Trinidad and Tobago, Tunisia, Uganda, Vanuatu and Yemen.

In February 2018, however, the European Council criticised the list for too closely following a register maintained by the Financial Action Task Force, a worldwide standards-setter for anti-money laundering. The group of EU finance ministers that comprise the European Council argued the methodology used should be more transparent and better tailored to the specific threats facing Europe.

The commission responded by tabling a significantly amended list in February last year.

That would have seen eight countries added – The Bahamas, Botswana, Ghana, Libya, Nigeria, Panama, Samoa and Saudi Arabia – as well as US territories American Samoa, Guam, Puerto Rico and the US Virgin Islands.

Five nations would have been removed: Bosnia and Herzegovina, Guyana, Laos, Uganda and Vanuatu.

But the updated list was rejected by the European Council in March 2019 after ministers again claimed it “was not established in a transparent and resilient process that actively incentivises affected countries to take decisive action”.

European Parliament representatives had also previously questioned the wisdom of including important EU trade allies on the list, given the possibility banks could become more risk-averse to clients operating in those jurisdictions.

Cristian Dan Preda, then a Romanian MEP, said in February 2018 the inclusion of Tunisia was “incomprehensible”, adding: “If we tell these people that we want to help them and that they are our partners, [then] blacklist them ourselves, they will not understand anything.”

Sullivan’s Cook says that if countries that remain listed despite efforts to remove them are likely destinations for the trade finance market “then it’s a potential issue”.

“Certain institutions would be put off looking at transactions there merely by the fact that they’re on a list, even if they shouldn’t be, while others may be put off because the extra due diligence they have to carry out means extra costs,” he says.

The European Commission is now due to produce a new proposed blacklist using an updated methodology, but there is so far little indication of when that work is likely to be completed.

Using external providers for due diligence

Although toughening due diligence requirements can often impact the trade finance sector disproportionately – not least because transactions often involve large numbers of parties – some parts of the new directive could prove more helpful.

“For example, you’ve got some provisions relating to the ability within parameters to use external providers for part of the on-boarding due diligence process,” Cook says. “Before, everybody was very hesitant about relying on external providers in order to on-board customers, but there is now some scope for the use of those processes. It will now be about how it is put into practice.”

The previous directive only specified that due diligence information should be collected from a reliable and independent source. But new wording in 5AMLD explicitly lets banks use information obtained from “electronic identification means, relevant trust services… or any other secure, remote or electronic identification process regulated, recognised, approved or accepted by the relevant national authorities”.

Further ahead, that could open the door to third-party repositories of information vital to trade finance banks.

“Ultimately, where the industry would like to get to in order to make on-boarding clients and carrying out due diligence for transactions as easy as possible would be to have databases set up that have up-to-date verified information that banks can just tap into, rather than having to obtain information from the parties every time a new financier tries to on-board a customer and/or enter into a transaction,” Cook says.

“This would make the whole process a bit more streamlined, but obviously this has to be balanced with the current regulatory approach.”

Global financial messaging giant Swift has long advocated for sharing due diligence information, launching an online KYC Registry in 2014. Though initially only open to financial institutions that are members of Swift’s network, the registry has since been made available to corporates too.

Elsewhere, Mansa, a due diligence platform focused on Africa, has been developed by the African Export-Import Bank, and a group of six Nordic banks established a new joint venture last year to support a common utility that simplifies customer onboarding.

Bank account registration rules

Another way the new directive seeks to increase transparency around the movement of funds is to establish electronic registers that allow authorities to identify whoever holds or controls a bank account.

EU member states are expected to set up central registers or data retrieval systems by September 10 this year, while the European Commission is tasked with assessing how those national-level databases can be interlinked. According to Cook, that means the burden of providing that information may fall on financial institutions.

“Bank accounts are used a lot in trade finance transactions as they are generally receivables-backed deals, whether it’s a structured trade finance deal or receivables deal,” he says.

“The upshot is that banks – and this applies on a wider basis as well – will have to ensure that all relevant details of bank account beneficial ownership is passed through to this register.

“It’s not clear at the moment exactly whose responsibility that will be, or how that information is going to be provided, but it is likely to be the account bank because they’re the ones who know their customer.”

Relief over registration of trusts

Because the new rules take the form of a directive, rather than a regulation, they do not automatically apply once the EU deadline arrives. Instead, countries are required to write the directive into their national rulebook.

Occasionally, that can create the opportunity for slight deviations from the EU-level text. In the case of the UK, that has been positive for the trade finance sector. HM Treasury decided shortly before the January deadline to remove a potentially problematic provision around the registration of trusts.

“In theory, any pre-existing trust would have to be registered, which would be a phenomenal number,” explains Sullivan’s Cook. “It would have been inconceivable come January 10 for everybody to be able to register every single trust in the prescribed time.”

Seemingly recognising the issue, the Treasury removed all mention of expanding the trust registration scheme in its final statutory instrument issued in December.

Cook says HM Treasury is expected to revisit the issue, but it is not yet known whether a carve-out could be created for trusts used only for financing techniques, whether a revised scheme would be produced, or whether that requirement will be scrapped entirely.