Over a year into the Covid-19 pandemic, Eleanor Wragg looks at the potential for trade to recover in the Middle East and North Africa, and explores some of the main challenges faced by the region.

After experiencing a decline in GDP of 3.4% in 2020, the Middle East and North Africa (Mena) region will grow by 4% this year, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which recently revised its October projection of 3.2% upwards as countries begin the path to recovery from the Covid-19 crisis.

While this outlook is still lower than the IMF predictions for global growth of 6% for 2021, it is decidedly more rosy than that of July last year, when the twin shocks of the pandemic and low oil prices prompted the IMF to slash the region’s economic forecast to its lowest level in 50 years.

However, these positive projections mask enormous variance across the region, and with several downside risks affecting Mena’s overall trade outlook, 2021, arguably more than any other year, looks set to mark a series of disparities across this extremely heterogenous region.

Export outlook

According to research by Oxford Economics, China and the US are leading the global trade recovery over this year and next, with export growth of 18.1% and 7.9% in 2021, respectively.

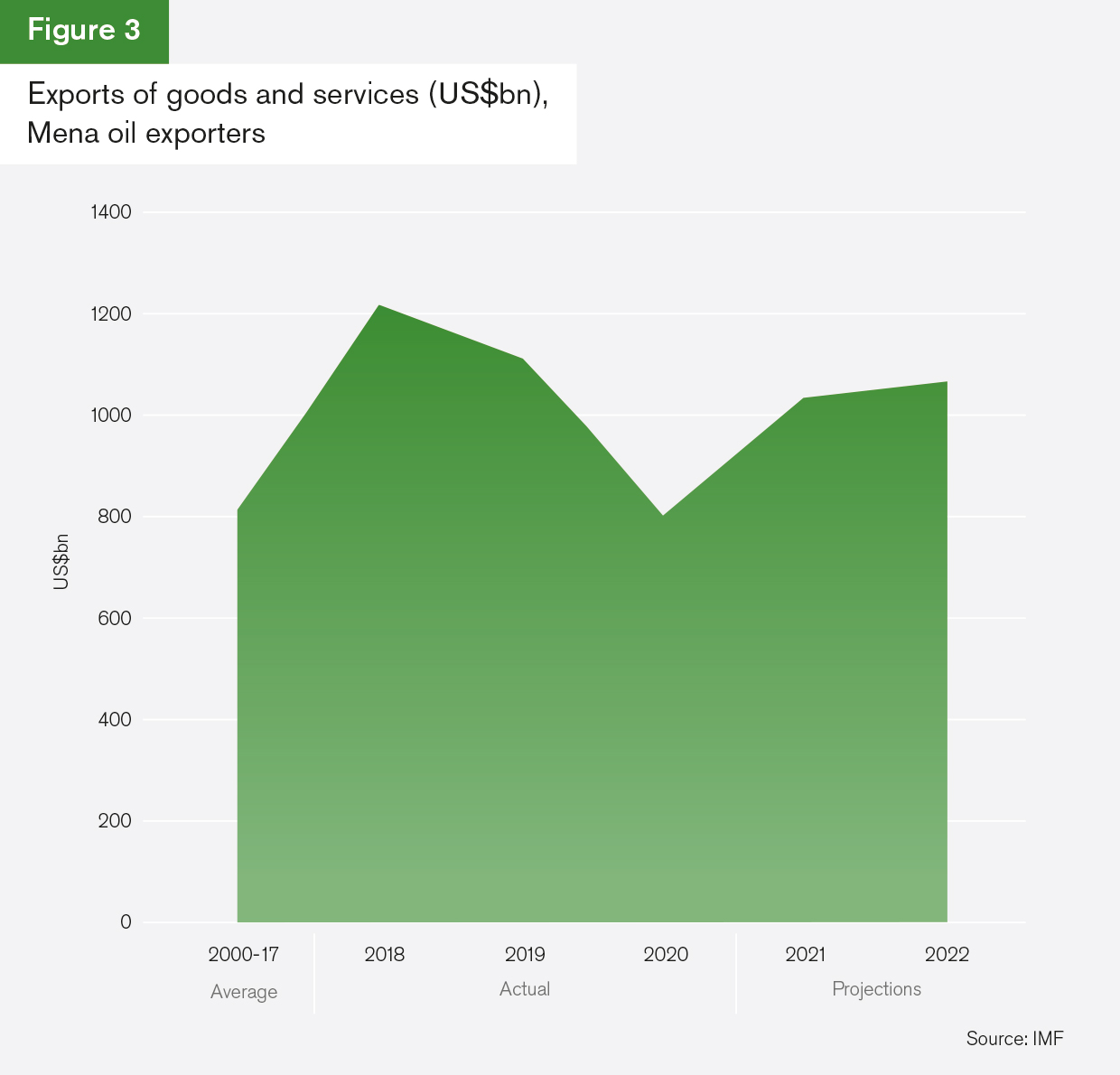

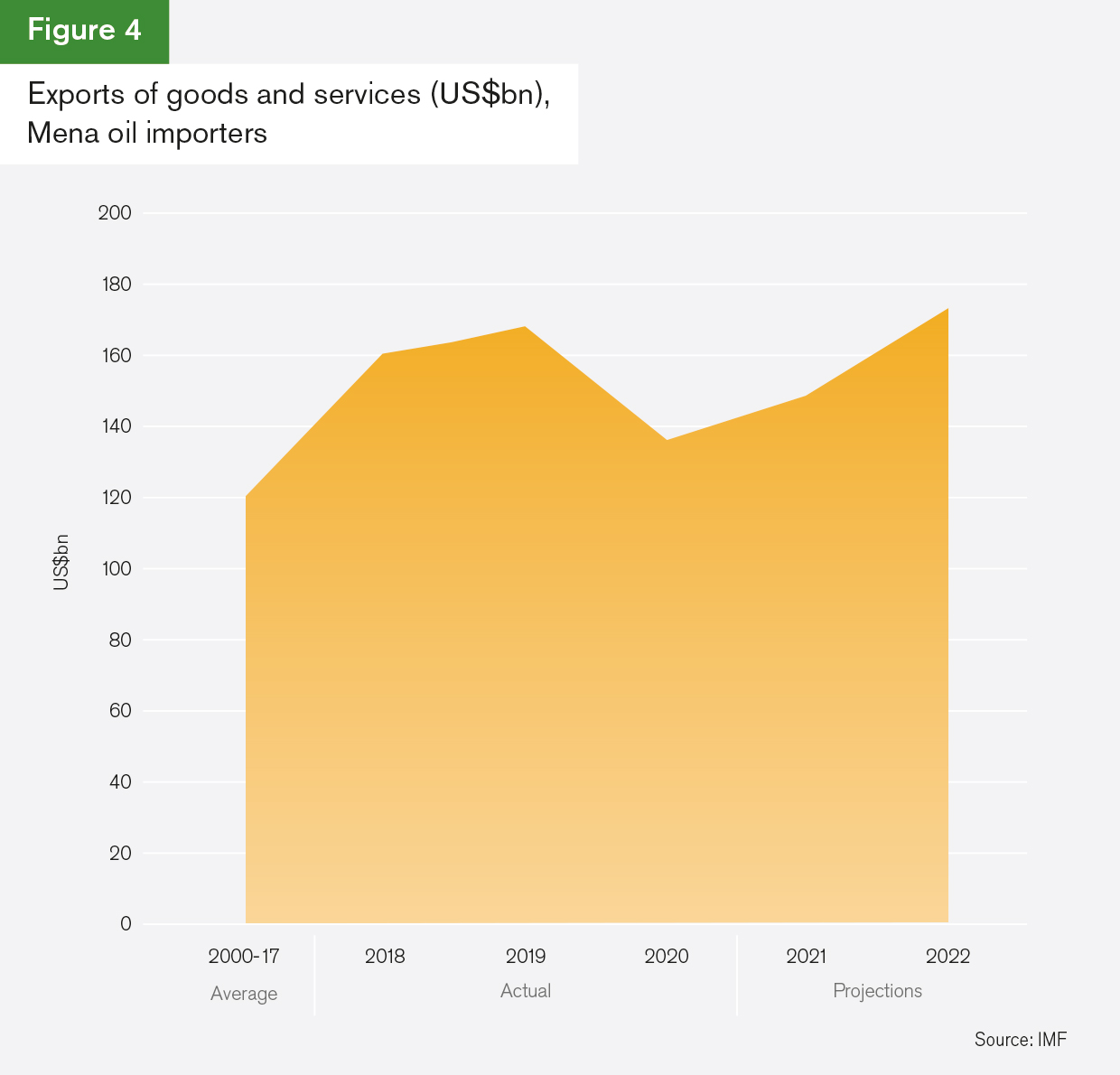

Mena’s goods trade – which has been in decline since 2019 – will stage a slightly more muted recovery, growing by 3% in 2021 and a further 5.1% in 2022, which will bring it some way back towards pre-pandemic levels.

A closer look at the figures reveals a two-speed Mena. While the GCC countries – the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Oman, Kuwait and Bahrain – will see export growth of 2% this year, North Africa, which is dependent upon Europe for tourism, remittances and exports, suffered a more abrupt slowdown, with recovery not expected to unfold until 2022.

Whether this trade outlook comes to pass, however, depends on numerous factors, says Nasser Saidi, former minister of the economy of Lebanon and CEO of economic consultancy and advisory firm Nasser Saidi & Associates.

“There are several major areas that are problematic,” he tells GTR. “The first is oil. The region is still highly dependent on oil and it is not just the oil producers. What happens to the oil price and global demand for oil is critical. The second is the pandemic, and the way in which the dynamics of Covid infections and vaccination rollouts are now linked to the economy and trade. The third is country risk in Mena’s export markets. Another risk is in the recovery of services trade, and this matters not only for the countries of the Mediterranean but increasingly for the GCC, because they have been looking at tourism, trade services, logistics and transport as a way of diversifying their economies. Given all of these risks, it is highly probable that the region may not see the recovery in trade that it is hoping for.”

Oil dynamics and the need for export diversification

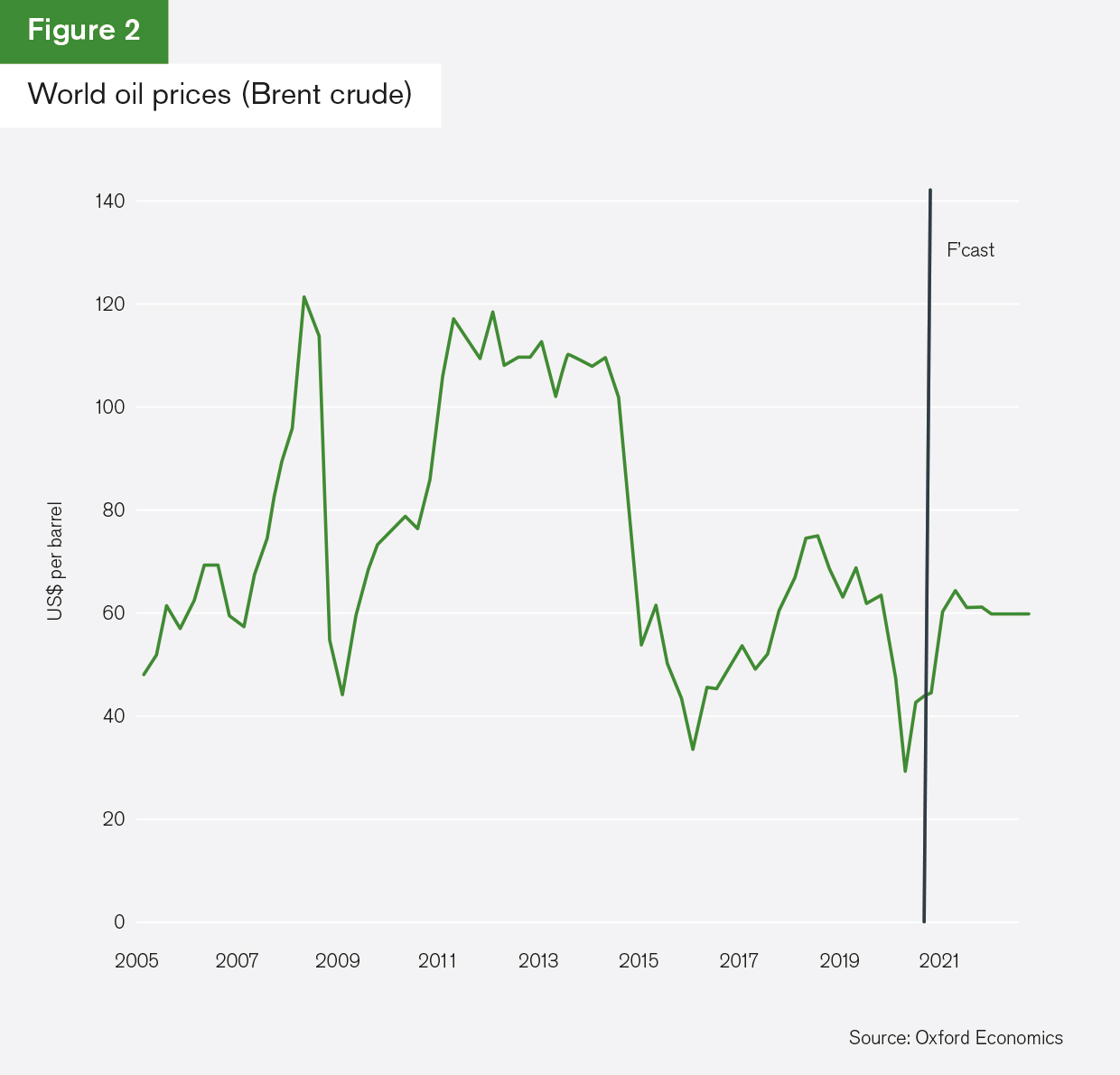

The first half of 2020 saw a sudden and unprecedented decline in oil demand due to the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic, followed by an oil price war between Russia and Saudi Arabia when the two sides failed to reach consensus on production levels. Together, these events forced West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude to go negative for the first time on record.

While the oil price has since recovered somewhat, rapid changes in behaviour in the wake of the pandemic and a stronger drive by governments towards a low-carbon future will mean that oil will continue to face unprecedented demand destruction, and it seems unlikely that prices will top US$60 per barrel in the coming years.

This is forcing hard decisions on oil-producing countries, where collapsing oil revenues caused fiscal deficits averaging 10.5% of GDP in 2020, according to the IMF’s latest regional economic outlook.

“Longer-term measures are needed for fiscal sustainability and to reduce governments’ vulnerability to fluctuations in oil prices,” says Scott Livermore, chief economist for the Middle East at Oxford Economics, adding that pressure is growing on Gulf states in particular to push ahead with developing non-oil export sectors. “We are likely to see increased public spending to support diversification efforts, especially in Saudi Arabia and the UAE,” he adds.

The GCC’s ambitious development programmes – Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030, the UAE’s Vision 2021, Kuwait’s Vision 2035, Oman’s Vision 2040, Qatar’s National Vision 2030, and Bahrain’s Economic Vision 2039 – have all been set up to address this, but progress is slow in developing goods and services, other than hydrocarbons and their derivatives, that can be traded with the rest of the world. According to research carried out by Brookings, the latest data available shows that hydrocarbons and related products represent over 90% of total exports in Kuwait and Qatar, over 80% of total exports in Saudi Arabia and Oman, and over 50% of total exports in the UAE and Bahrain.

As a result, overall export growth for oil exporting countries in Mena will be weaker than that of its non-oil producing economies over the next two years.

That said, the fundamentals in the GCC remain strong, and a number of special factors such as Expo 2020, preparation for the World Cup in 2022, the Abraham Accords, the end of the blockade with Qatar and spending by the Public Investment Fund in Saudi Arabia will also contribute to growth across the GCC, says Livermore. “Based on high frequency indicators such as purchasing manager indices for the non-oil sector, Google Mobility trends and hotel occupancy rates, economies across the GCC held up better than feared in Q1 2021 following the rise in new Covid-19 cases and increased lockdown stringency globally, and it seems likely the non-oil sector in most of the GCC continued to grow, albeit at a slower pace than in the second half of 2020.”

Covid vaccines: the key to recovery, and a gateway to strengthening trade relations

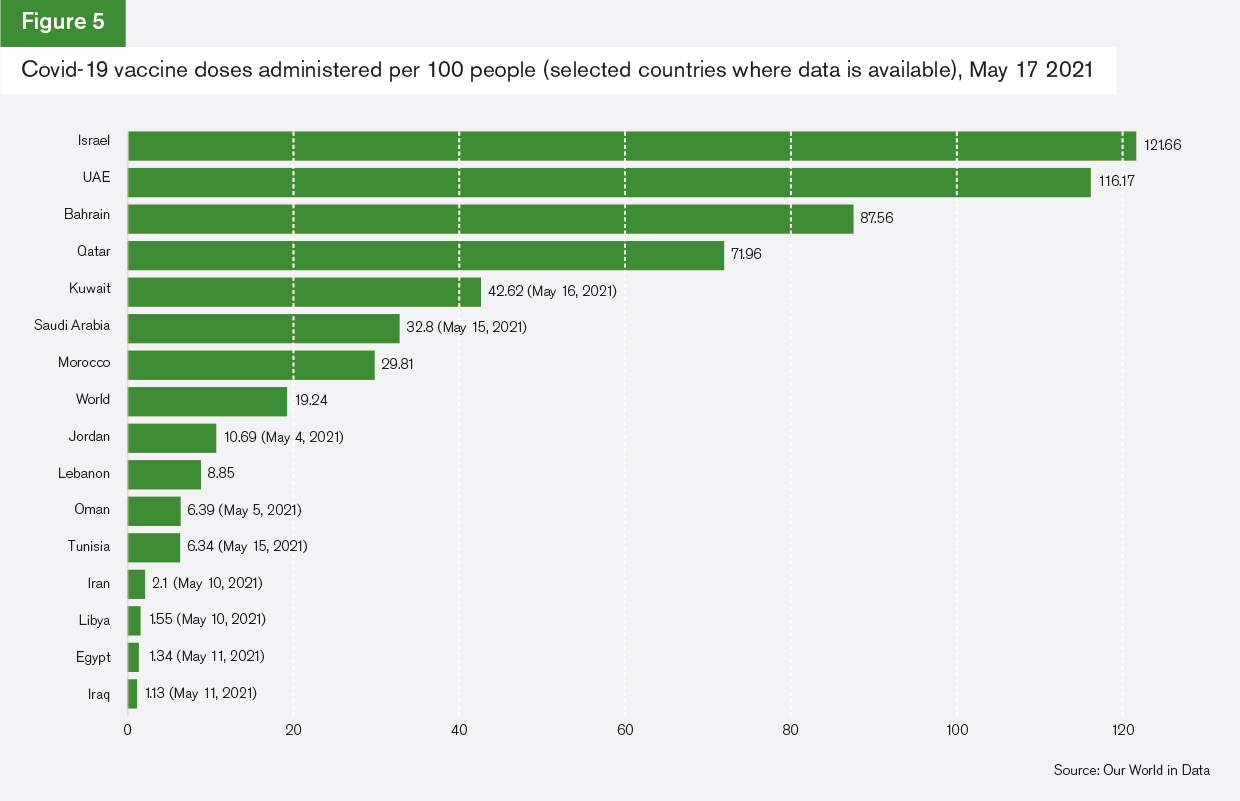

As in the rest of the world, the rate of recovery in Mena in 2021 hinges on the pace of Covid-19 vaccinations – but not all countries in the region are making much headway. While Israel, the UAE, Bahrain and Qatar have surged ahead, as this publication goes to press, most nations in Mena have administered fewer doses per capita than the global average.

“The GCC provides an interesting case study of how the vaccine programme impacts upon the response of countries to rising new cases of Covid-19,” says Oxford Economics’ Livermore. “Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman and Qatar have all seen significantly higher new daily cases of Covid-19 over the past month [April/May 2021]. This has resulted in tightening of lockdown restrictions in Oman and Qatar and maintaining of tight restrictions in Kuwait to quell the spread of the virus and ease pressure on health services.

“On the other hand, Bahrain, which has one of the world’s most rapid vaccine rollouts, has actually eased lockdown conditions despite a steep rise in new daily Covid-19 cases. This mirrors the UAE where new daily cases were brought back down despite continued relatively easy lockdown restrictions. This could also feed into a difference in the speed with which economies in the GCC recover over the summer months.”

Amid the unprecedented vaccine rollout, China has sought to enhance its influence in the region with a number of high-profile deals. The Sinopharm vaccine, produced by the Beijing Institute of Biological Products (CNBG) forms the cornerstone of campaigns in the UAE and Morocco, and has also made inroads in Egypt, Bahrain, Iraq and Algeria.

“The most interesting thing about the vaccine diplomacy in regard to China and the Middle East is that although the UAE could afford to buy the more expensive Pfizer vaccine, they chose to buy the Chinese one. Not only that, but they have also signed a production agreement which will see the Chinese vaccine distributed from Abu Dhabi to the rest of the region,” Roie Yellinek, non-resident scholar at the Middle East Institute, tells GTR.

These vaccine ties will likely result in the strengthening of long-term trading relationships, says Saidi. “Covid is going to be with us for a couple of years at least if not longer. What this means is that through the licensing deals, China is establishing long-term relationships and therefore integrating these countries into its supply chain. This is not a one-off. The Chinese, thinking long-term, want to reward participants in the Belt and Road Initiative. It is the health Silk Road.”

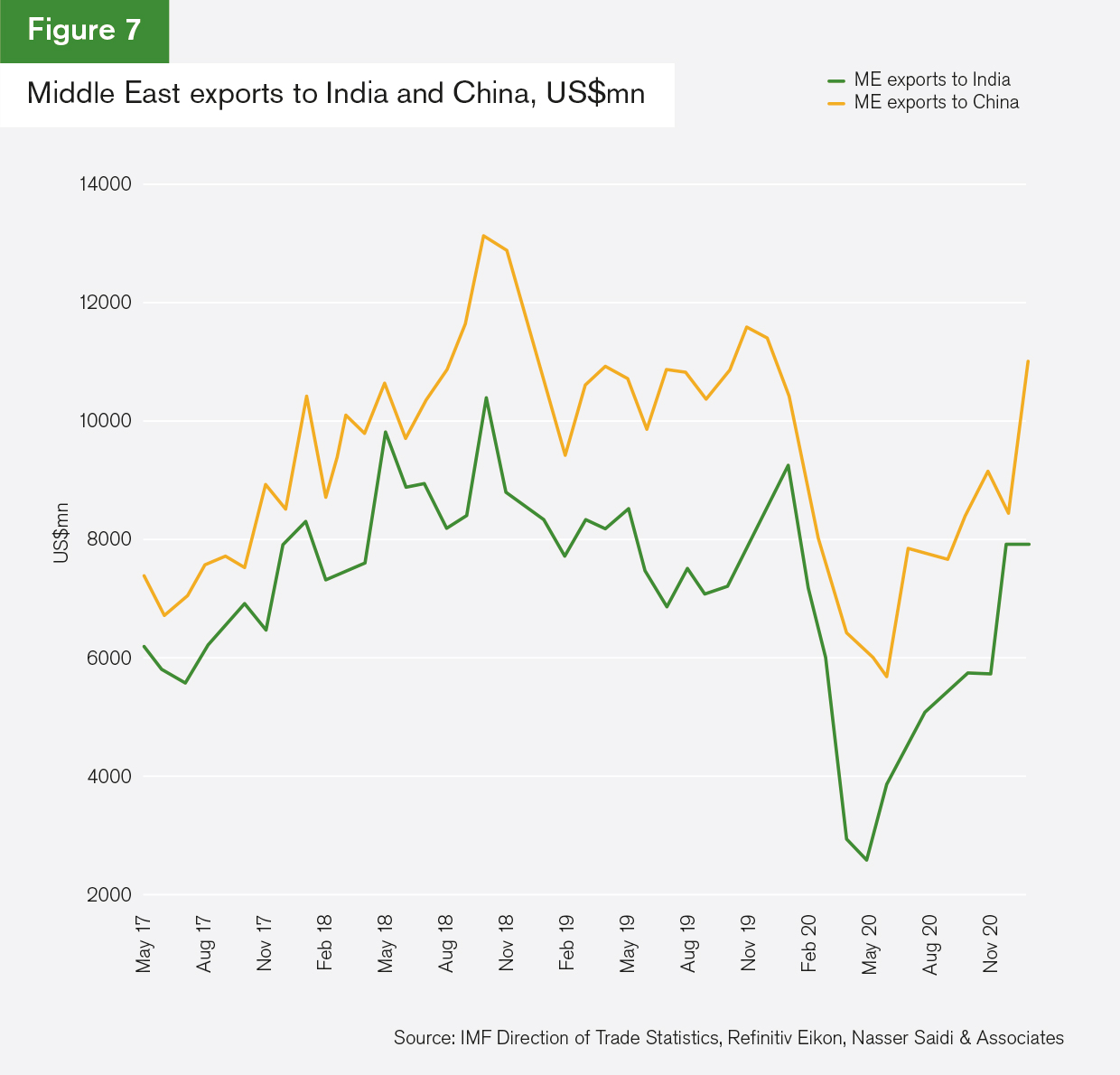

The ever-closer ties with China contrast with weakening trade figures with Mena’s other Asian trading partner – India – as the South Asian nation struggles to contain the Covid-19 outbreak.

“India is undergoing a serious crisis as a result of the pandemic, and this situation is not likely to end any time soon,” says Saidi. “It is a major trade partner for Mena, and the third biggest importer of oil in the world. It is also a major tourist market for the GCC, and a source of labour.”

A new US-Mena relationship under Biden

Four months after taking office, indications are that, for US President Joe Biden, making any sweeping changes to the US’ trade and foreign policy as it concerns the Mena region is likely to be low on the list of priorities.

“The new administration has built its foreign trade policy around its domestic ‘Build Back Better’ agenda, putting the American economic recovery above all other objectives,” Ruben Nizard, US economist at Coface tells GTR. “Hence, the trade policy laid out so far does not signal any major shift with its predecessor in the Mena region.”

That said, President Biden’s energy and climate policy – he has announced a goal of achieving a 100% clean energy economy and net-zero emissions no later than 2050 – may affect trade with Mena, and potentially on the upside. “The US shale boom bolstered oil and gas production in the last decade, to the extent that the country recorded a trade surplus with Mena in 2019 and 2020. However, President’s Biden willingness to move away from fossil fuels – as demonstrated by an executive order banning oil drilling on federal land signed earlier in 2021 – could mean a reversal of that trend, which could, in the short term, mean higher oil imports from Mena,” says Nizard.

Another main shift in policy which could affect trade is the US’ stance towards Iran. In a reversal of course after former President Donald Trump in 2018 withdrew the US from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action signed three years previously under the Obama administration, Tehran and Washington started informal talks at the beginning of April 2021, signalling the first step towards a deal.

“An easing of the sanctions would be good news for Iranian trade, and more specifically for its crude oil exports with the world – currently curbed by the extraterritoriality of US jurisdictions,” says Nizard. “The latter, which were as high as 2.8 million barrels per day before the re-instatement of sanctions in 2018, were reported at around 500,000 barrels per day in Q1 2021. However, reactions of regional rivals to a potential nuclear deal with Iran are to be monitored: it might spark some geopolitical tensions in the Gulf.”

If a deal were to be reached, Oxford Economics estimates that this could boost Iran’s GDP growth in 2021 to 6%, surpassing pre-sanction levels by 2023.

In the meantime, Iran continues to strengthen its regional and international alliances that would help the country to counter rising US pressure and overcome its economic challenges. In late March, the country signed a 25-year co-operation agreement with China, aimed at strengthening their economic and political alliance.

“This accord is very strategic as it brings Iran into China’s Belt and Road Initiative,” says Selem Iyigun, Middle East economist at Coface. “Through the agreement, China is expected to become a permanent crude oil and natural gas client of Iran while it will also invest in its key railroads and ports to use it within the Belt and Road Initiative. Under these circumstances, the US can consider the return to the nuclear deal with Iran as a way to contain rising Chinese influence in the region.”