Although Africa is set to post above-average economic growth this year, sluggish demand from major export markets and the continued impact of the Russian invasion of Ukraine are weighing on its trade prospects. Eleanor Wragg explores some of the key factors shaping the continent’s outlook.

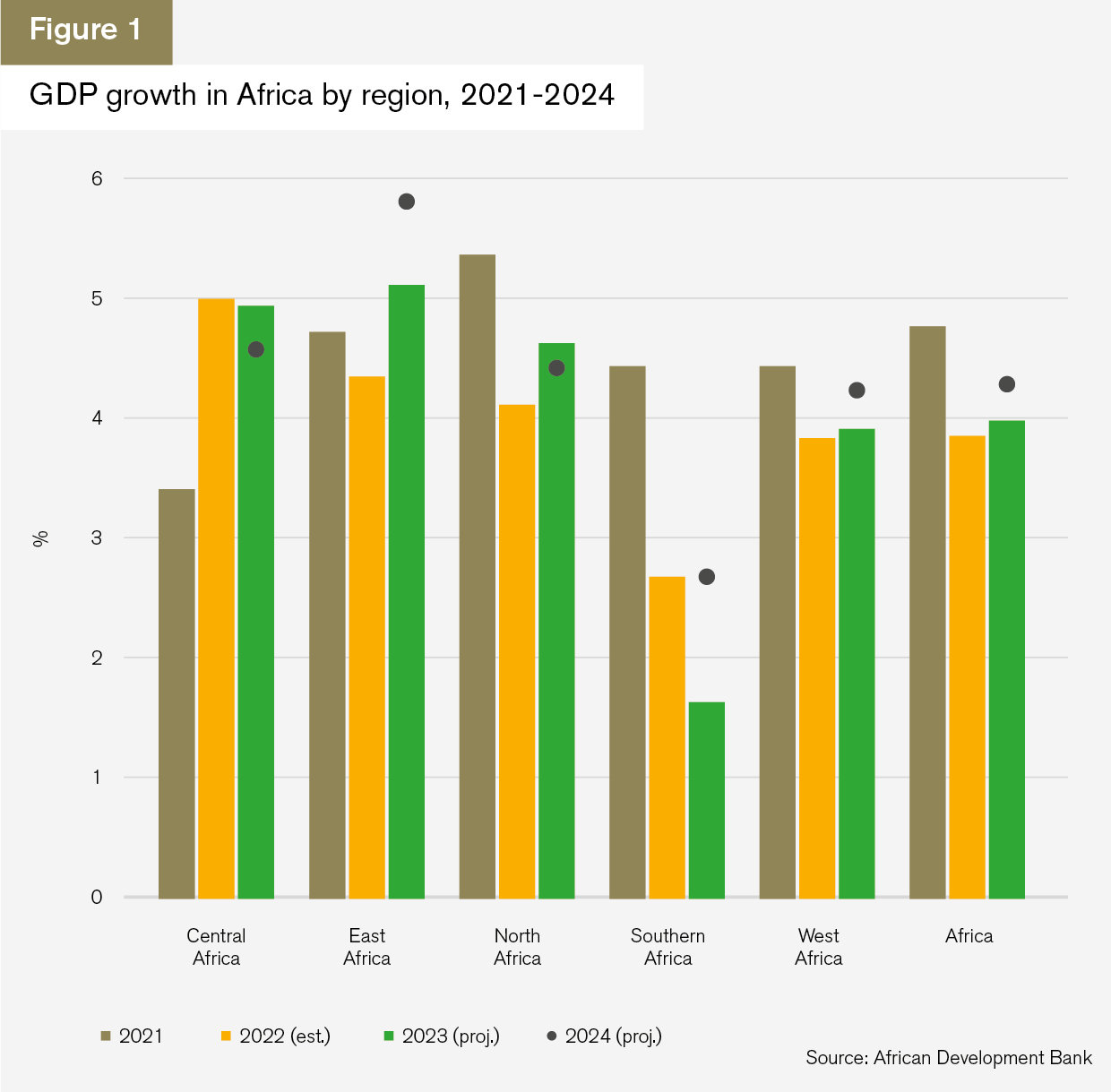

Following a tough 2022, Africa is now set to regain its position as the world’s second fastest-growing continent, trailing only developing Asia, according to the latest figures from the African Development Bank (AfDB). Although global economic growth is expected to reach just 3% in 2023, the continent is tipped to notch up a 4% increase, with a further consolidation to 4.3% in 2024.

“This continued resilience will be reinforced by expected improvements in global economic conditions, fuelled by China’s reopening and a downward adjustment of interest rates as the effects of monetary policy tightening on inflation start to bear fruit,” says AfDB president Akinwumi Adesina in the multilateral institution’s Africa Economic Outlook Report 2023, published in May.

“Growth in oil-exporting countries is expected to benefit from oil prices, which, despite the recent decline, remain elevated. Non-resource-intensive economies will gain from their more diverse economic structures, highlighting the importance of diversification in withstanding shocks.”

As a diverse and heterogeneous continent made up of 54 sovereign states encompassing the full range of income groups, economic growth continues to vary widely across countries and sub-regions.

As figure 1 shows, growth in Central Africa – which mainly comprises net exporters of crude oil, minerals and other commodities such as timber – is expected to moderate to 4.9% in 2023, from 5% last year. A strong showing from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, which is expected to post GDP growth of 6.3% thanks to the scaling up of investment and exports in the mining sector, will be tempered by a decline in GDP of 1.8% in Equatorial Guinea amid falling oil production.

East Africa, which was the only sub-region to escape a recession during the Covid-19 pandemic, continues to demonstrate resilience, with 2023 GDP growth forecast at 5.1%, up from 4.4% last year. Among the drivers of this growth are developments in the oil sector in Uganda and increased mineral exports in Rwanda.

Driven by oil production growth in Libya, North Africa is expected to achieve growth of 4.5% this year, while West Africa is projected to expand by 3.9%.

With a 2023 growth outlook of just 1.6%, Southern Africa is the continent’s worst performer, due in large part to South Africa’s current economic woes. The country, which posted GDP growth of 2% last year, is tipped to experience a sharp deceleration to just 0.1% in 2023, due in large part to structural weakness and an intensification of power outages.

Trade performance

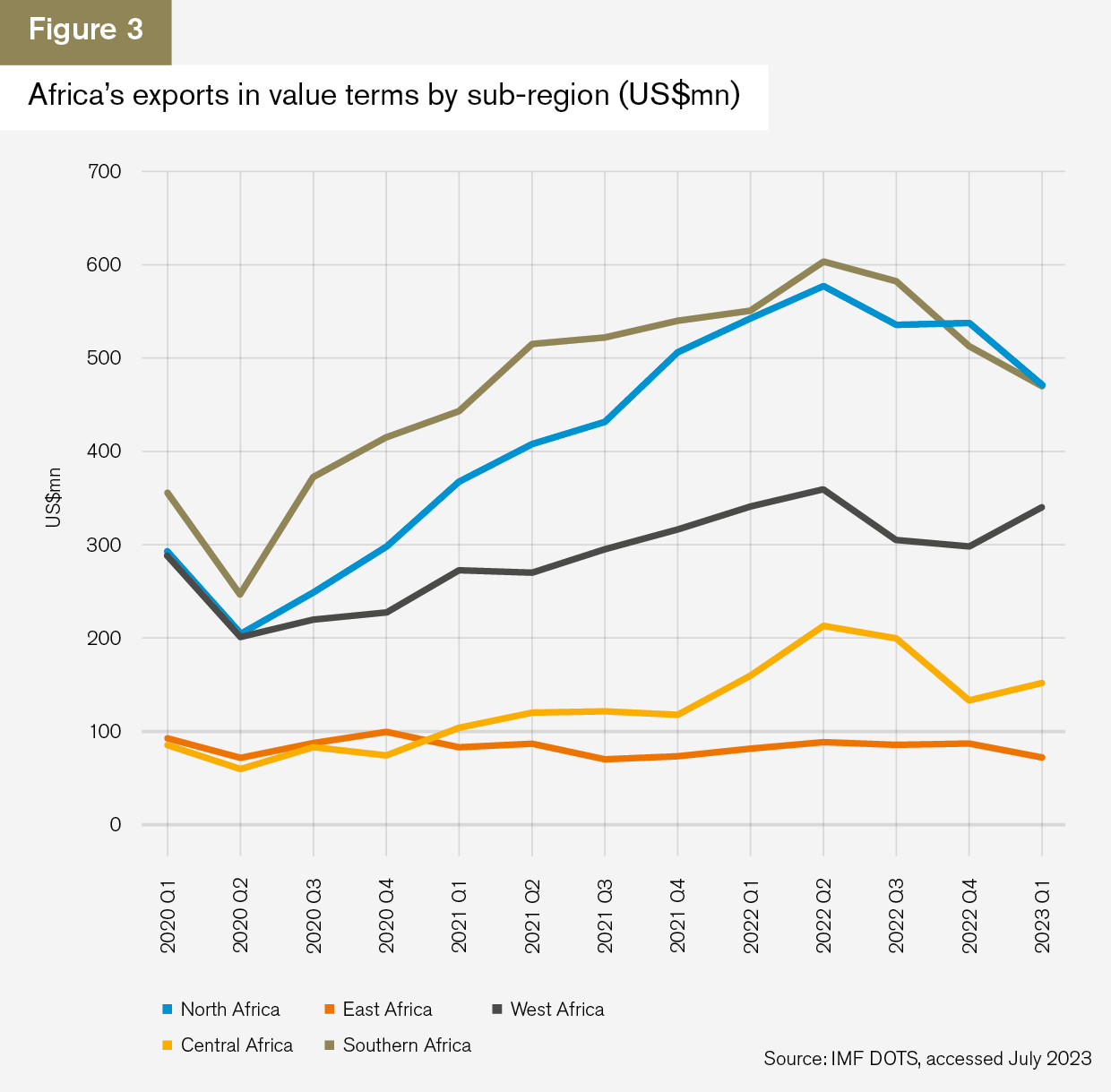

In value terms, after reaching a peak of US$184.4bn in the second quarter of 2022, Africa’s post-pandemic export rebound is beginning to level off, as the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) Direction of Trade Statistics (DOTS) show (figure 2). Nonetheless, export values remain above pre-Covid levels.

But, as in the case of GDP growth, trade performance differs markedly across Africa’s sub-regions. As figure 3 shows, North Africa has now overtaken Southern Africa as the continent’s top exporting sub-region by value.

Exports from East Africa – defined by the AfDB as Burundi, Comoros, Djibouti, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Kenya, Rwanda, Seychelles, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Tanzania and Uganda – have remained steady since 2019. However, at the individual country level, there are some standouts, most notably Tanzania, which has seen exports more than double from US$1.07bn in the first quarter of 2019 to US$2.17bn in the first quarter of 2023.

Export outlook

In volume terms, Africa, which last year posted a sluggish 0.7% growth in exports, is set to become the only global region to see a contraction this year, with World Trade Organization (WTO) economists forecasting a year-on-year decline of 1.4% for the continent – as compared to global growth of 1.7%.

The main factor behind this decrease is ongoing global macroeconomic volatility, which is also changing the shape of Africa’s trade flows. Asia accounts for almost half of the continent’s merchandise exports, but as figure 4 shows, China’s economic slowdown amid prolonged lockdowns has significantly reduced its demand for African commodities, with the country now accounting for around 11% of the continent’s exports, down from a peak of 16%. Meanwhile, India’s share dropped from 9% in 2019 to 5% by the end of last year, as Indian traders increasingly buy discounted Russian oil to replace African crude. The European Union’s (EU) share of the continent’s exports has increased as a result, and may climb further as the EU continues to move away from dependence on Russian fossil fuels.

Opportunities for gas exporters

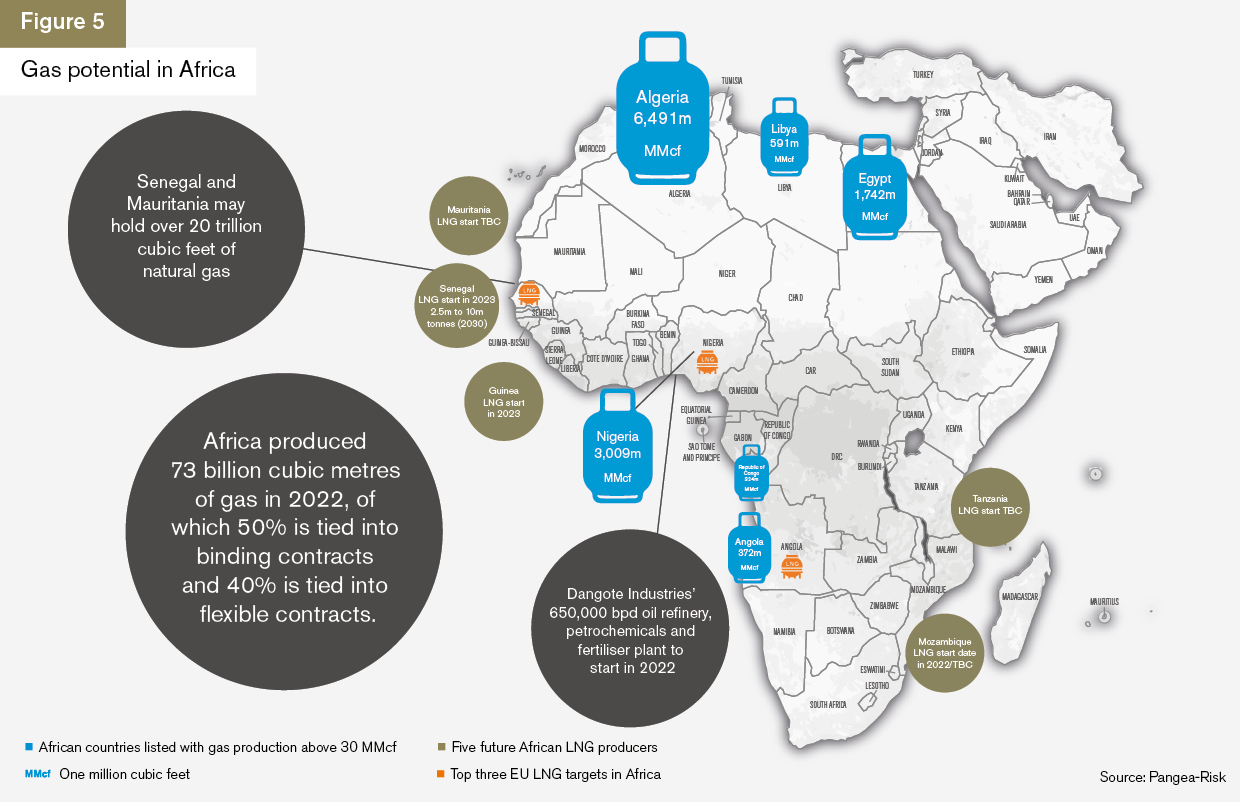

As Europe refocuses its energy strategy, its governments are increasingly looking to gas-rich African nations to scale up production and exports in the years to come.

“Key for 2023/24 is the launch of gas sectors in important economies like Senegal, while Mozambique and Tanzania are about to see record investments into gas resumption or kick off,” says Robert Besseling, CEO of specialist intelligence consultancy Pangea-Risk.

According to the Global Energy Monitor’s latest Global Oil and Gas Extraction Tracker, recent entrants to Africa’s gas market – Mozambique, Senegal, Tanzania, Mauritania, South Africa and Ethiopia – are expected to drive gas development volumes in the near term, accounting for more than half of Africa’s gas production by 2038.

As international oil companies rebalance their strategies after withdrawing from Russia, Africa is seeing the revival of stalled projects, among them a long-delayed LNG export terminal on Tanzania’s Indian Ocean coast. In June last year, Shell and Equinor – both of which have announced exits from Russia – signed a framework agreement with the Tanzanian government to speed up the start of the US$30bn project, with negotiations concluding in March this year.

A 2022 decision by the European Commission to endorse fossil gas as a “transition” fuel under its sustainable finance taxonomy is also opening the way for further investments, which were until recently disincentivised by European banks.

However, with an estimated US$329bn of investment required for the development of gas extraction and transport infrastructure, it is unclear how quickly Africa will be able to increase its exports.

“In the near-term, not many large volumes are expected to come online,” the African Energy Chamber says in its State of African Energy 2023 Outlook. “Overall, Africa natural gas output is expected to experience a marginal decline from 2022 through 2025. Ramp up is expected through the second half of this decade as Mozambique ramps up its LNG output and new gas startups across the continent come online and take the output on an increasing trend.”

AfCFTA yet to make its mark on trade

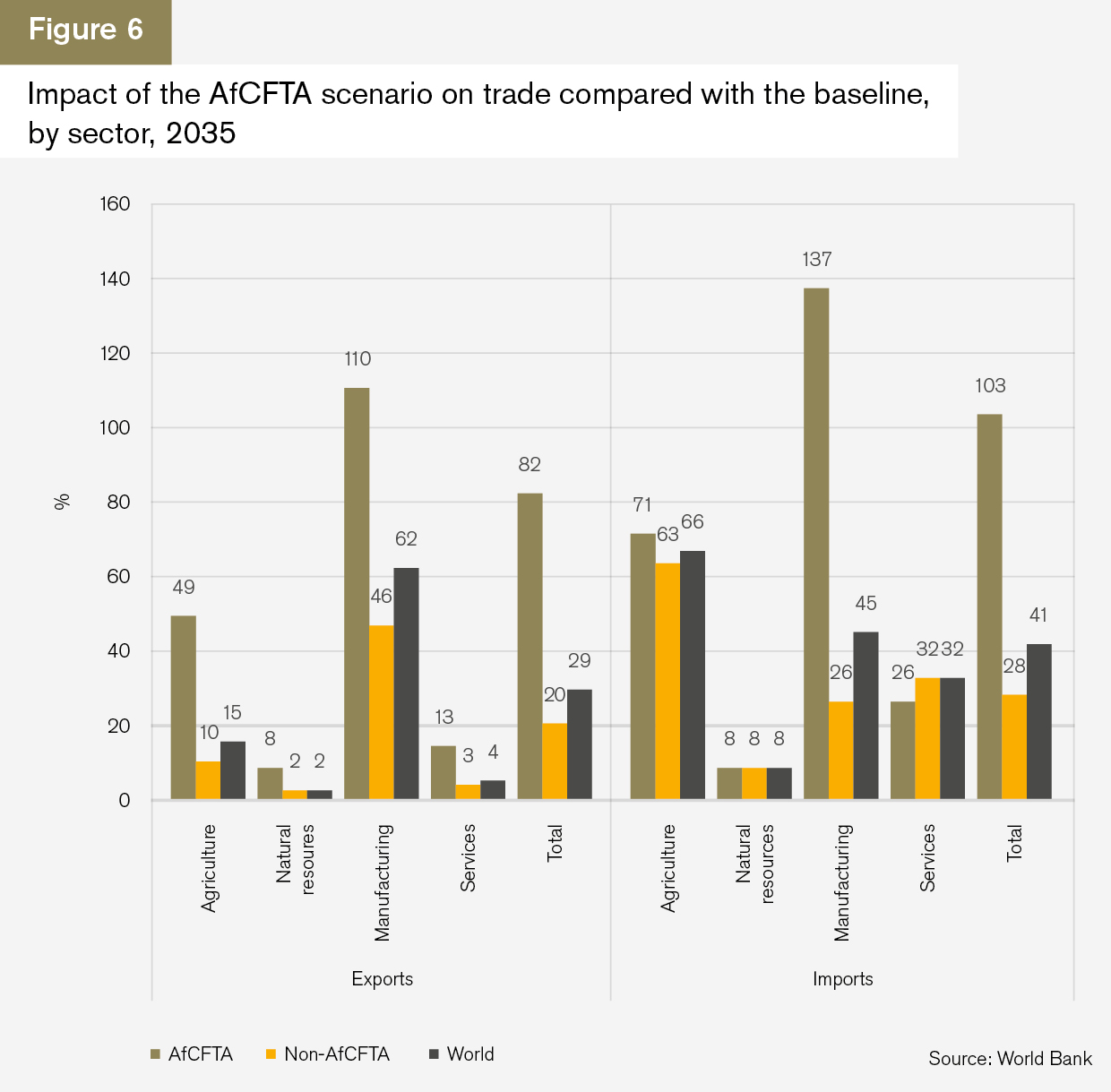

The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) came into force on January 1, 2021. According to World Bank estimates (see figure 6), the deal will lead to an increase in intra-African exports of 109% by 2035 – with most of the growth coming from manufactured goods – as well as drive up Africa’s exports to the rest of the world by 32%.

Progress on operationalising the AfCFTA is underway, with eight countries – Cameroon, Egypt, Ghana, Kenya, Mauritius, Rwanda, Tanzania and Tunisia – piloting the duty-free trade of 96 products, including rubber, sugar and processed meats under the AfCFTA Secretariat’s Guided Trade Initiative.

Meanwhile, the African Export-Import Bank has launched a single electronic window that brings together key parts of Africa’s digital ecosystem for trade.

The Africa trade gateway (ATG) is one portal that gives access to five digital platforms – customer due diligence platform Mansa; the Pan-African Payment and Settlement System, a scheme that enables payment for intra-African trade in national currencies; the Tradar Club, a network for international businesses aimed at fostering growth in Africa; e-commerce platform the Africa trade exchange; and ATG Connect, which provides freight and logistics connectivity solutions.

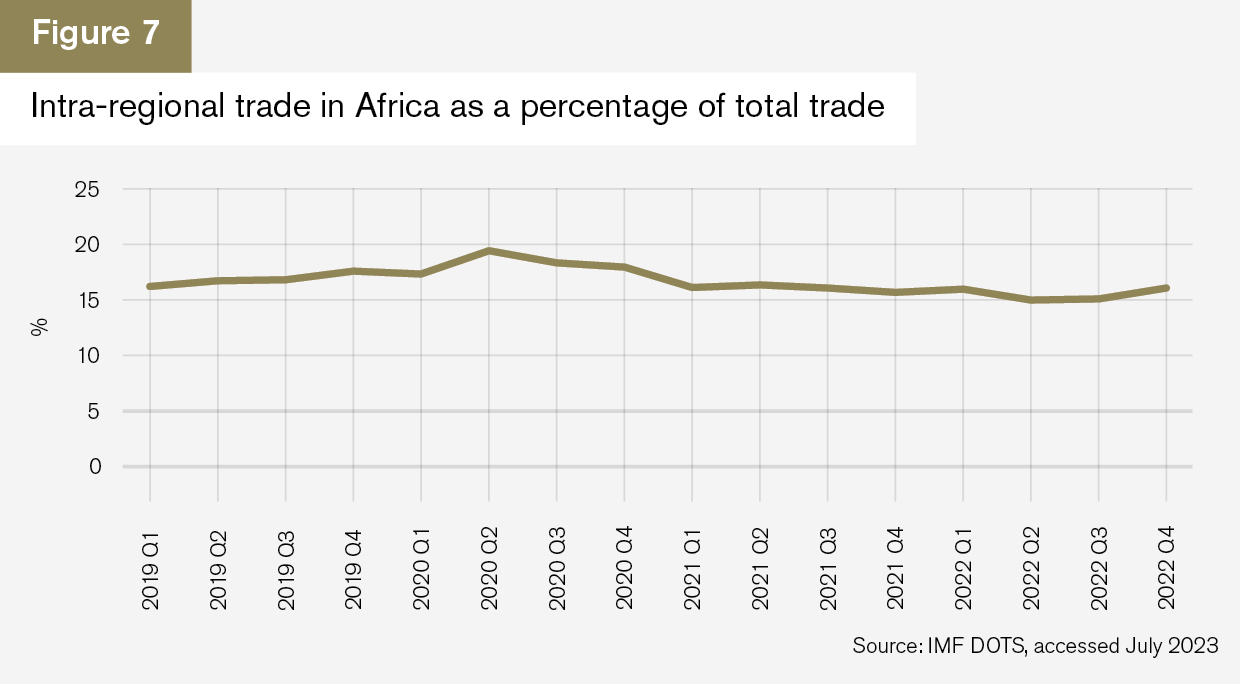

However, little trade has yet taken place under the regime due to implementation challenges, and Africa’s intra-regional trade continues to account for the same proportion of its total trade – around 16% – as it did at the beginning of 2021 (see figure 7).

Uncertain times for soft commodity imports

2022 saw soaring prices for agricultural commodities amid restricted supply from Russia and Ukraine. Almost half of Africa depends on these markets for more than a third of its wheat imports. A blockade of Ukraine’s Black Sea ports, which trapped 20 million tonnes of grain, exacerbated food insecurity in African countries already struggling with climate change and Covid-19.

A solution was found in the shape of the Black Sea Grain Initiative, brokered by the United Nations (UN) and signed by the governments of Ukraine, Russia and Turkey in July 2022, which enabled shipments of corn, wheat, sunflower products and other soft commodities to leave Ukraine.

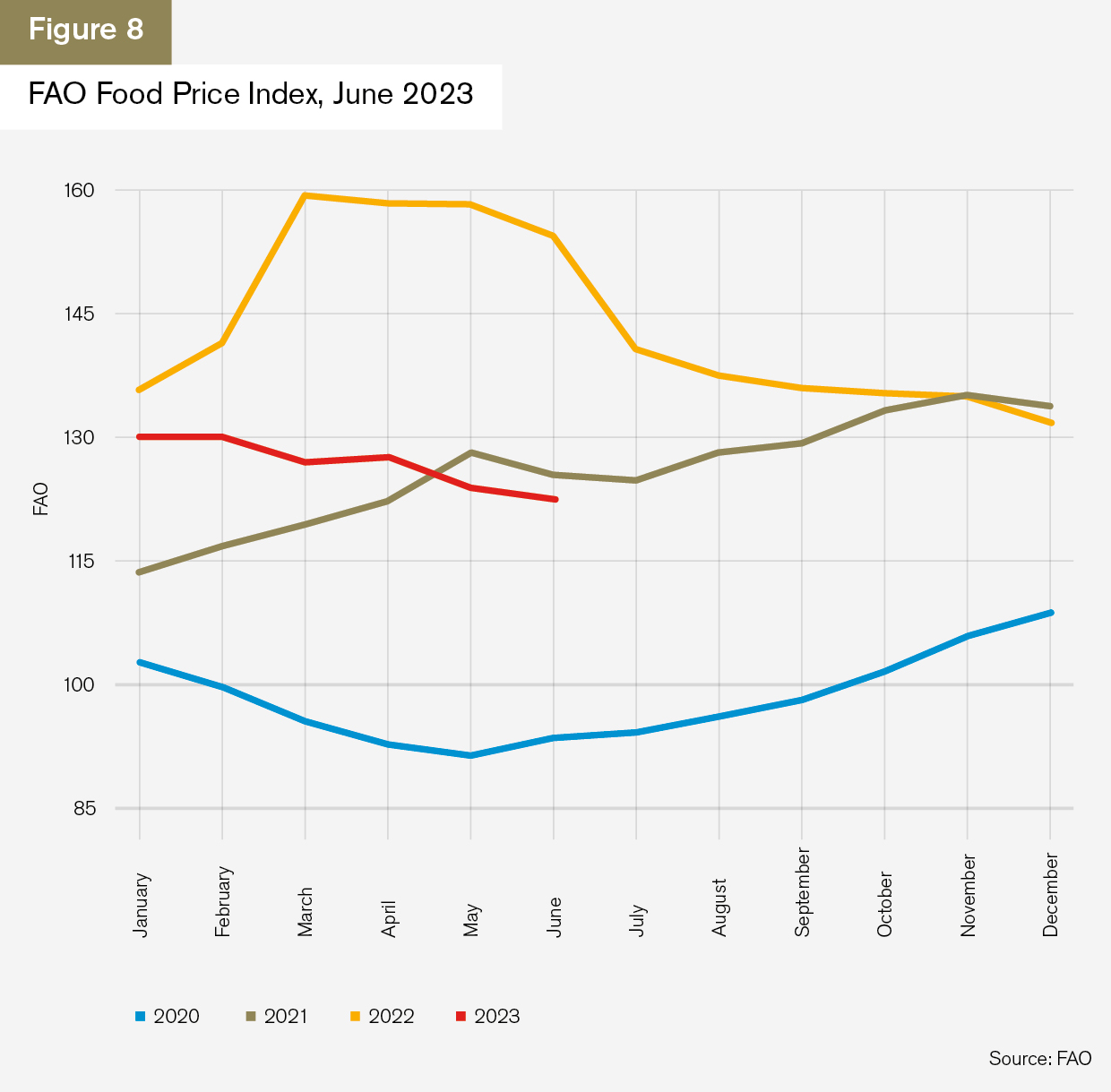

The deal helped stabilise global food prices: in the latest read-out, the Food and Agriculture Organization’s (FAO) Food Price Index (see figure 8) was at 122.3 points in June 2023, continuing its downward trend since reaching an all-time high in March 2022.

In addition, according to WTO research, many vulnerable economies were able to find substitute products and suppliers to obtain essential foodstuffs.

Ethiopia, for example, relied on Russia and Ukraine for 14% and 31% of its wheat imports in 2019, respectively. In the initial 10 months of the conflict, its imports in volume terms from Russia fell by around 75% while imports from Ukraine dropped to almost zero. However, the volume of its total wheat imports remained stable, as the country was able to increase shipments from the US by 21%. In addition, Argentina, which exported no wheat at all to Ethiopia in 2021, supplied roughly 20% of the country’s wheat in 2022.

Similarly, Egypt, the world’s largest importer of wheat, increased its sourcing from suppliers including the EU – imports from which rose by 128% in 2022 – and the US.

“Overall, the data show that trade in products and by countries highly dependent on supply from Russia and Ukraine was remarkably resilient,” says the WTO in its One year of war in Ukraine report. “An important part of this seems to be importers sourcing products from other suppliers. Countries either switched suppliers for the same product or replaced products with substitutes, which also required establishing trading relationships with new partners.”

As a result, in most African countries, food price inflation has declined markedly (see figure 9), reducing the potential for social and political unrest.

The Black Sea Grain Initiative was short-lived. In July this year, Russia announced its withdrawal from the pact, citing sanctions-related issues that were affecting its fertiliser and food exports.

In a statement condemning the decision, the EU said: “By terminating the agreements, Russia is single-handedly blocking one of the crucial main export routes from Ukraine of grains for human consumption and is solely responsible for disruptions of grain deliveries worldwide and fuelling food price inflation globally.”

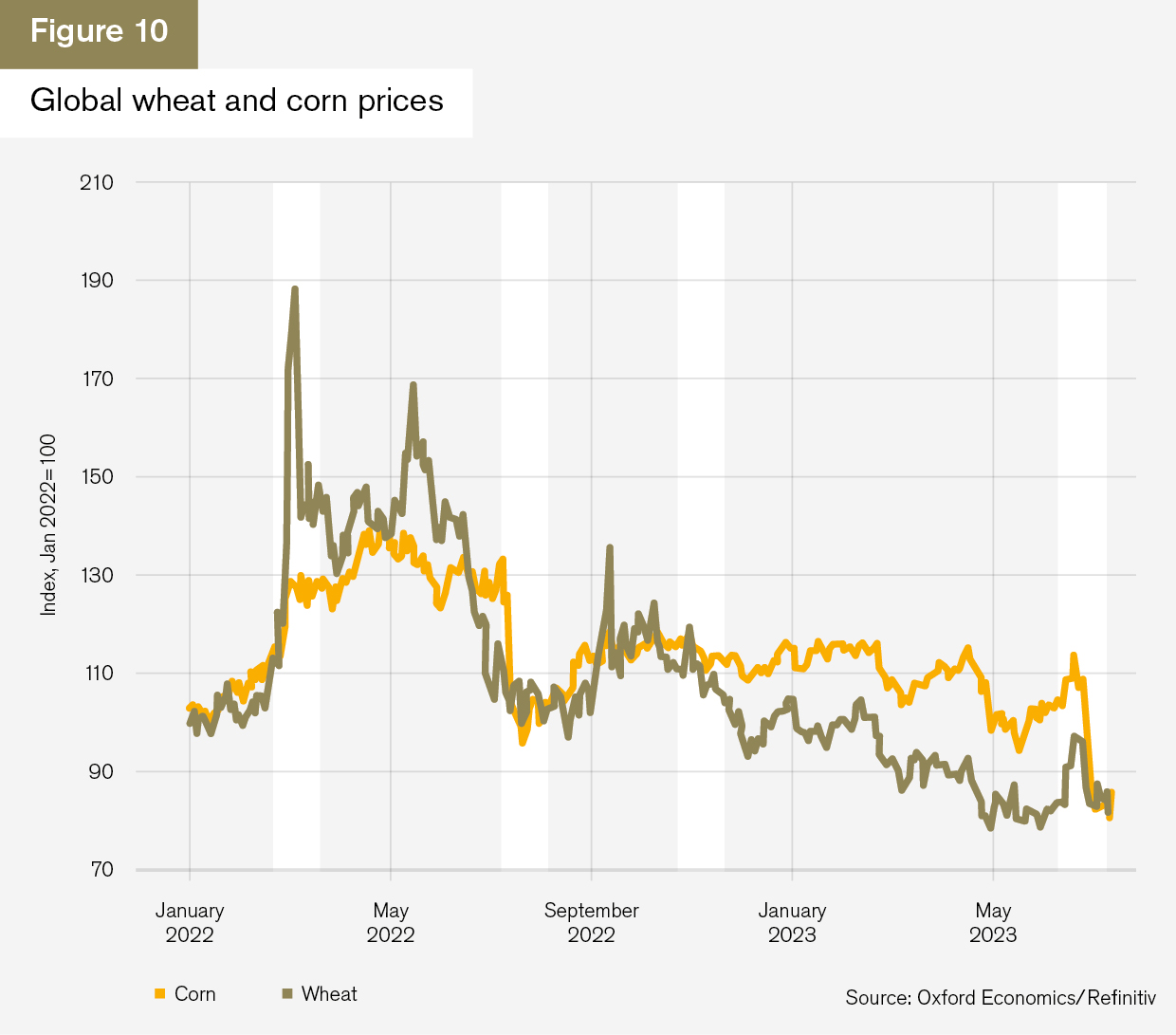

While the move is likely to cause inflationary pressures, better global supply and lower current grain prices are making markets less sensitive to any supply disruptions from Ukraine (see figure 10).

“Despite the better global market environment, we don’t believe the deal will remain suspended for a long time,” says Evghenia Sleptsova, senior emerging markets economist at Oxford Economics, in a research note. “China, Turkey and Egypt have been the top recipients of Ukraine’s grain exports (ranking the first, third and sixth largest importers of Ukraine’s grain, respectively), and would be keen to see the deal renewed. Besides, Russia still needs Turkey as a critical trade partner, including for imports that it can no longer get from the West.”

During the Russia-Africa summit held in St Petersburg on July 27-28, African leaders pressured Russia to return to the deal. In response, President Vladimir Putin pledged to replace Ukrainian grain exports to Africa, and promised to send as much as 50,000 tonnes of grain to Burkina Faso, the Central African Republic, Eritrea, Mali, Somalia and Zimbabwe “free of charge”.

However, as of press time, there are some indications that Russia is considering restarting the initiative, according to comments made by Linda Thomas-Greenfield, the US representative to the UN, on August 1.