Covid-19 has had a profound effect on South Africa’s metals and minerals trade. Strict lockdown measures resulted in a staggering drop in output from one of the world’s mining powerhouses, while logistical issues made exporting goods difficult and expensive. With authorities still struggling to bring the pandemic under control, calls are growing for the mining industry to modernise. John Basquill reports.

In terms of confirmed cases and deaths, the coronavirus outbreak has hit South Africa harder than any other country on the continent. Despite President Cyril Ramaphosa imposing strict lockdown measures towards the end of March, the virus has continued to spread at an alarming rate; as of press time the number of confirmed cases stands at more than 275,000 while the official death toll is over 4,000.

With all sectors of the country’s economy stuttering, it is unsurprising that mining has made headlines. South Africa is the world’s largest producer of platinum and chrome, and one of the biggest producers of gold, diamonds and palladium.

Overall the sector represents around 8% of the country’s GDP, and according to World Bank data metals and minerals exports totalled US$23.5bn in 2018.

Since lockdown, output has plummeted. Government statistics show that in April 2020, the first full month of lockdown, total mining production fell by more than 47% year-on-year. The figure for gold was 60%.

At the same time, there have been concerns that Covid-19 has spread particularly rapidly within the mining community. Data provided by the Minerals Council of South Africa shows that of the 27,000 employees tested by mid-July, over 18% had the virus. 34 of the 39 workers who died were mining gold or platinum.

The country is not expected to exit lockdown quickly, and as of July 13 has re-imposed a curfew on all citizens requiring them to stay home between 9am and 4am, other than for work travel or medical attention.

Coupled with lingering problems around logistics – not least at the country’s congested ports – there are now serious questions around how South Africa can revive its ailing extractive industries and put its economy back on track.

Logistics problems

One issue facing South African exporters has been difficulties at the country’s ports. Initially, when a strict 21-day lockdown was announced, restrictions applied to all but essential movement of both goods and people, prompting national port operator Transnet to inform clients that all terminals for mineral and mining commodities would be immediately closed.

Within a day, the situation had changed. Concerns had been raised over the potential impact on trade, and Transnet swiftly issued another statement saying terminals and staff would operate “as per demand from mining customers”.

Because some gold, chrome, manganese and iron ore production was allowed to continue – a practical consideration, given the difficulty of switching smelters on and off – that demand never reached zero. Neighbouring Namibia, Botswana and Zimbabwe have also restarted mining operations albeit with stringent safety precautions.

By the start of April, that flexibility had been enshrined into law. Changes to the Disaster Management Act meant lockdown rules would not apply to “transportation of cargo from ports of entry to their intended destination, on condition that necessary precautions have been taken to sanitise and disinfect such cargo”.

“All borders of the republic are closed during the period of lockdown, except for ports of entry designated by the responsible cabinet member for the transportation of fuel, cargo and goods during the period of lockdown,” the amended bill says.

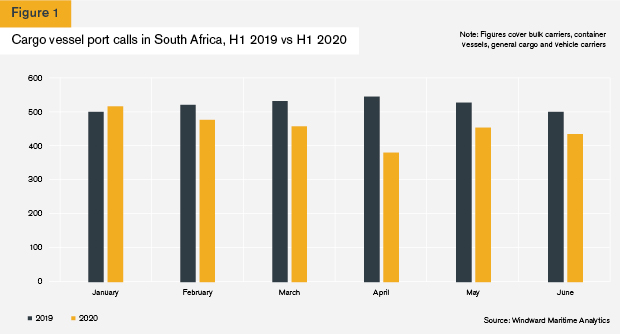

Data provided by Windward Maritime Analytics shows that port calls in South Africa by cargo vessels dropped 14% in March and 30% in April 2020 compared to the equivalent months in 2019.

Lockdown restrictions affecting other parts of the economy also had a knock-on effect on ports. With almost all South African businesses closed by law, goods they had imported could not legally be delivered and were instead piled into warehouses. At the same time, containers that had to be stored at ports incurred hefty surcharges.

David Logan, chief executive of the South African Association of Freight Forwarders, told reporters at the time that businesses were bracing for “increasing pressure in terms of exorbitant detention costs”, adding: “Even at this stage, the amounts involved are very high and we are aware of invoices running into many millions of rand already.”

Cape Town was worst affected. A June 30 notice issued by Transnet said marine operations were only operating at 60% of their human resources capacity, and that employees had been transferred from Durban to alleviate pressure at the terminals.

Durban, Sub-Saharan Africa’s busiest port, was also impacted. When lockdown measures were first imposed, reports emerged of trucks transporting copper from Zambia and Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) to the port being forced to divert elsewhere, including Dar es Salaam in Tanzania.

Geoffrey de Mowbray, founder and chief executive of logistics and financing firm Dints International, which works with clients across the mining industry, says the disruption to road transportation “has definitely been hard work”. The reduction in passenger flights was also challenging, he adds.

“I think capacity is recovering slightly, although it still remains a little expensive,” he tells GTR.

Uncertainty over financing

The pandemic has also impacted South African firms’ appetite for trade finance solutions.

Use of supply chain finance – which has experienced a surge in demand across the world as Covid-19 squeezes firms’ working capital – appears to be growing, says de Mowbray.

“We see that many buyers are looking to extend payment terms,” he says. “Suppliers are understandably nervous and so are being quite strict on not accepting extensions, and not increasing their risk. That is driving businesses to find more trade finance solutions that can support those payment terms.”

De Mowbray adds there have been signs of a contraction in credit insurance appetite, and though deals are still getting done, some may need “a bit more structure to them”.

“Not all the demand is coming in a way that is necessarily bankable, and that can be the case when it’s people who haven’t necessarily used those solutions to a large degree before,” he says.

Larger-scale transactions are still being arranged. Edward Baring, managing partner at Herbert Smith Freehills in South Africa, tells GTR the firm has recently been instructed on a chrome ore prepayment financing arrangement.

It is also working on “a similar large-sized transaction in relation to a DRC-based producer”, he says, though points out that it is currently difficult to assess whether demand more widely is greater than usual.

Baring adds that the transition to doing business digitally has helped ensure financing can still be obtained – even for arrangements across multiple jurisdictions that are all in lockdown.

“I was pleasantly surprised by how smoothly things went, with public authorities across Africa willing to accept electronically signed documents rather than ‘wet ink’ original signature pages for stamping purposes and/or currency control authorisations,” he says.

“Our deals are currently being done digitally in the sense that deal signings are being arranged as remote signings, with counterparties sending their signature pages by email instead of attending physical completion meetings and signing docs in person.”

Time to modernise?

A potentially transformative development off the back of the pandemic is that moves towards digitising or automating parts of the mining industry could be accelerated, according to some industry onlookers.

“Businesses are looking at how they can improve efficiency across the businesses. Behaviour is changing – doing meetings by Zoom is much more acceptable – but beyond that there’s been a lot more talk about autonomous machinery in mining,” says Dints’ de Mowbray.

“There’s obviously such high risk underground, with a lot of people working in close proximity. We’re also seeing more focus on the drone delivery side of things; it’s not quite there yet in terms of payload, but it’s getting there. I think this is going to drive some innovation.”

Similarly, Wessel Badenhorst, a managing partner at Hogan Lovells in Johannesburg, says the pandemic “may prove to be the ultimate disruptor or accelerator of change to the industry”.

“We will need new technologies to unlock the country’s remaining mineral wealth and this may include artificial intelligence and deep level remote mining employing skilled operators, rather than sending workers underground,” he says in an article published on the firm’s website in July.

However, there are complications around increasing automation within the mining industry. As Badenhorst acknowledges, with South African unemployment at around 30%, this “is an emotional issue, as the argument is often made that technology will replace employment”.

For that reason, Herbert Smith Freehills argues that the pandemic is actually more likely to slow moves towards automation.

“The crisis is likely to significantly delay mining companies’ roll out of larger scale autonomous operations, as for the foreseeable future it may be considered politically or socially unpalatable to reduce workforce numbers materially,” the law firm says in a legal briefing authored by several senior lawyers.

“That said, crises fuel innovation and create the conditions for expanded levels of creativity and problem solving. For those parts of the industry already focussed on innovation there will emerge new ways of thinking about old problems.”