The outbreak of Covid-19 has stirred the climate change debate, demonstrating how off-track we have ventured and highlighting the dangers of collective inaction. Keri Leicher, principal consultant at specialist intelligence company EXX Africa, takes a look at the role that renewable energy can play in combatting climate change in Africa.

Africa’s contribution to global greenhouse emissions is comparatively small, amounting to just 4% of the world’s total in 2017. The continent’s biggest emitters are South Africa, Nigeria, Ethiopia, Sudan, Tanzania, Angola, Cameroon, Kenya, Chad and the Central African Republic (CAR). The highest contributing sectors are energy, agriculture, industrial processes and waste.

While the continent is not the largest emitting region, it will be the most impacted by climate change over the long term: temperature rises in Africa are expected to be as much as 1.5 times more than the global average by 2100. Further indicative of this, according to the University of Notre Dame, the 20 most vulnerable states to climate change over the long term are all located in Africa. These include Somalia, Chad, Eritrea, the CAR, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Sudan, Niger, Guinea-Bissau, Burundi, Liberia, Madagascar, Zimbabwe, Mali, Republic of Congo and Ethiopia.

Nevertheless, with the odds against it, the continent is taking an increasingly leading role in combatting climate change. All 54 states have signed the 2015 Paris Agreement and submitted ambitious Intended National Determined Contributions (INDCs), for example, and almost all states have submitted their National Determined Contributions (NDCs), which ratifies these pledges, with the exceptions of Angola, Senegal and South Sudan. Moreover, at least 30 African states have already indicated an intention to enhance their NDCs in 2020 as part of the global effort to do more this year.

The development of renewable energy is often central to these commitments. Many of the biggest economies in Africa have come to realise this and are actively opening up investment opportunities in this space within their countries. Some of the most notable leaders in this regard are Kenya, Nigeria and South Africa, although a number of smaller economies are also following suit.

Kenya

Kenya is a continental and global leader in renewable energy exploitation, as these sources already contribute significantly (85%) to the overall energy mix in the country, largely as a result of geothermal and hydro power. This East African nation is already on track to meet or exceed its Paris Agreement pledge.

To this end, Kenya has a stated goal of achieving 100% of renewable energy power generation by 2030, to be complemented by a diverse technology mix. Although hydropower contributes significantly to energy production currently, given the risk of drought, the government is looking to enhance solar, wind, thermal and geothermal generation in its long-term plans. Geothermal generation specifically is expected to be prioritised over the next decade.

One of the ways in which Kenya is looking to achieve these goals is by entering into major public-private partnerships. This was demonstrated in August 2019 when the Kenyan Investment Authority and Meru County Government entered into a memorandum of understanding with global renewable energy developers to build Africa’s first large scale hybrid wind, solar PV, and battery storage project – the Meru County Energy Park. The park, for which construction began in January 2020, will provide up to 80MW of renewable energy and consist of up to 20 wind turbines and more than 40,000 solar panels. Power generated from the park is expected to supply 200,000 homes.

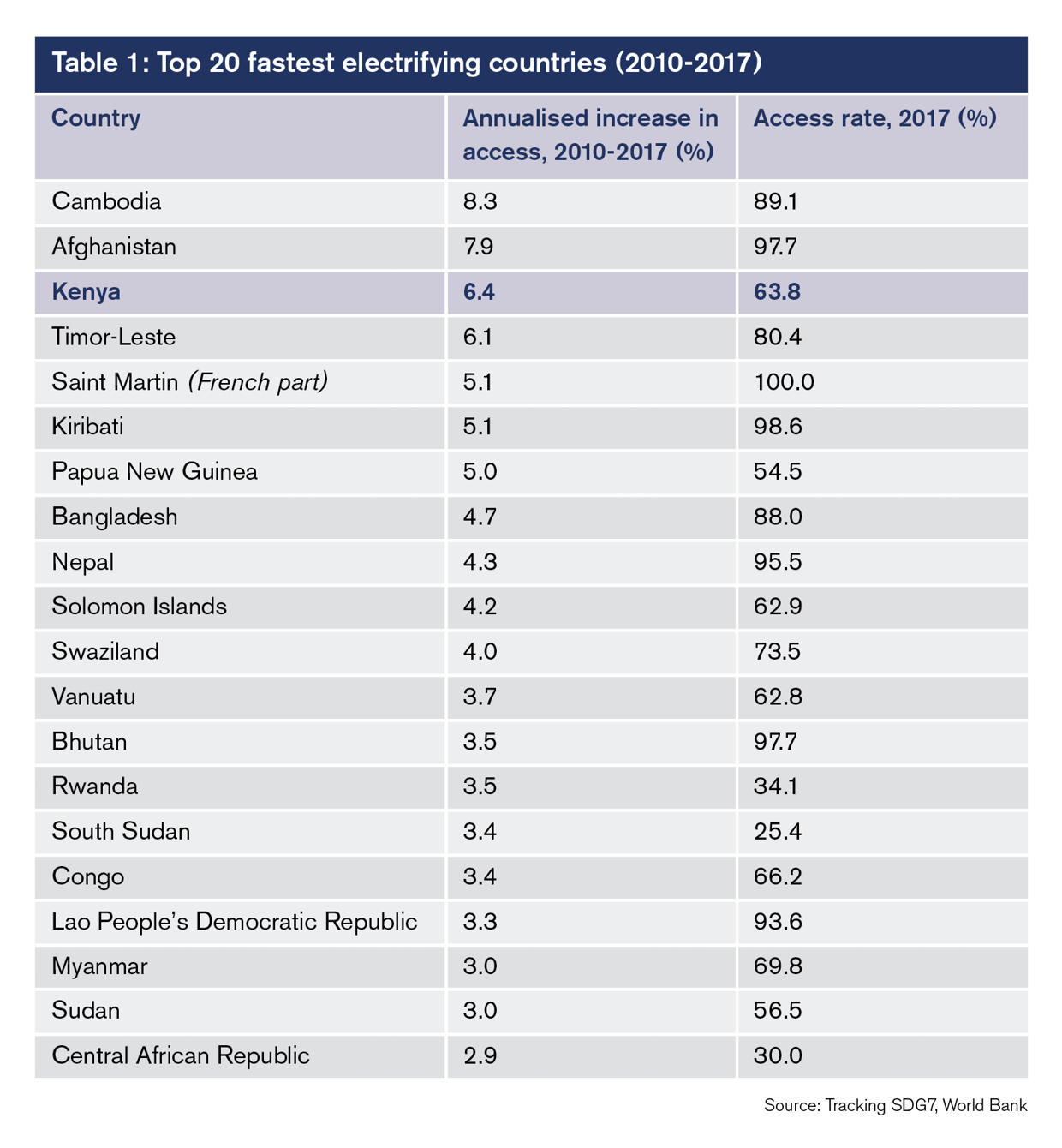

Harnessing renewable energy in Kenya will not only enable the country to meet its long-term climate goals but will ultimately help realise its ambition of becoming a middle-income country by the end of the decade. Part of this requires realising universal electricity access for its people and Kenya has made significant strides in this regard. Between 2010 and 2017, for example, Kenya was the fastest electrifying country in Sub-Saharan Africa (see table 1), according to the Tracking SDG7 Energy Progress Report by the World Bank. This was largely driven by last-mile electrification projects during this period that targeted informal settlements and rural communities.

By the end of 2019, the country’s energy ministry noted that 75% of Kenya’s population had access to electricity and that the country is looking to achieve universal electricity access by 2022 – meaning it could be one of the first Sub-Saharan African countries to realise 100% electrification. Kenya has indicated that it needs US$15bn in investment into various projects – geothermal, generation, off-grid, energy efficiency, transmission and distribution – to realise this goal and is actively looking for investors.

Nigeria

While Nigeria is endowed with vast natural resources that could be harnessed for renewable power, this potential remains largely untapped. Of its installed capacity, between 80-85% of electricity generation comes from thermal power. In an attempt to turn this around and address massive electricity shortfalls, the government has developed several plans to ensure growth in renewables over the next decade.1

The Nigerian Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency Policy (NREEEP), approved in April 2015, commits Nigeria to achieving a greater share of its national electricity supply from renewable energy sources by 2030. To achieve this, the country’s Renewable Energy Master Plan (REMP) intends to increase the supply of renewable electricity to 23% in 2025, and 36% by 2030. Through this, renewable electricity would then account for 10% of Nigeria’s total energy consumption by 2025 before being expanded to around 20-30% by 2030.2

While hydropower is the main source of renewable energy in Nigeria today, given the risk of drought, the country is looking to diversify its energy resource mix with a strong focus on solar. Indeed, the country boasts over 2,600 hours of sunlight per year – higher than the global leader in solar power, Germany. To this end, over 2017 and 2018, Nigeria invested more than US$20bn in solar power projects to boost the capacity of its national grid and reduce reliance on it by building mini-grids in rural areas without access to electricity. In a more recent move, in 2020, the government launched a US$75mn grant to encourage off-grid solar projects, while a US$350mn World Bank loan is currently being used to build 10,000 solar-powered mini-grids in rural areas.

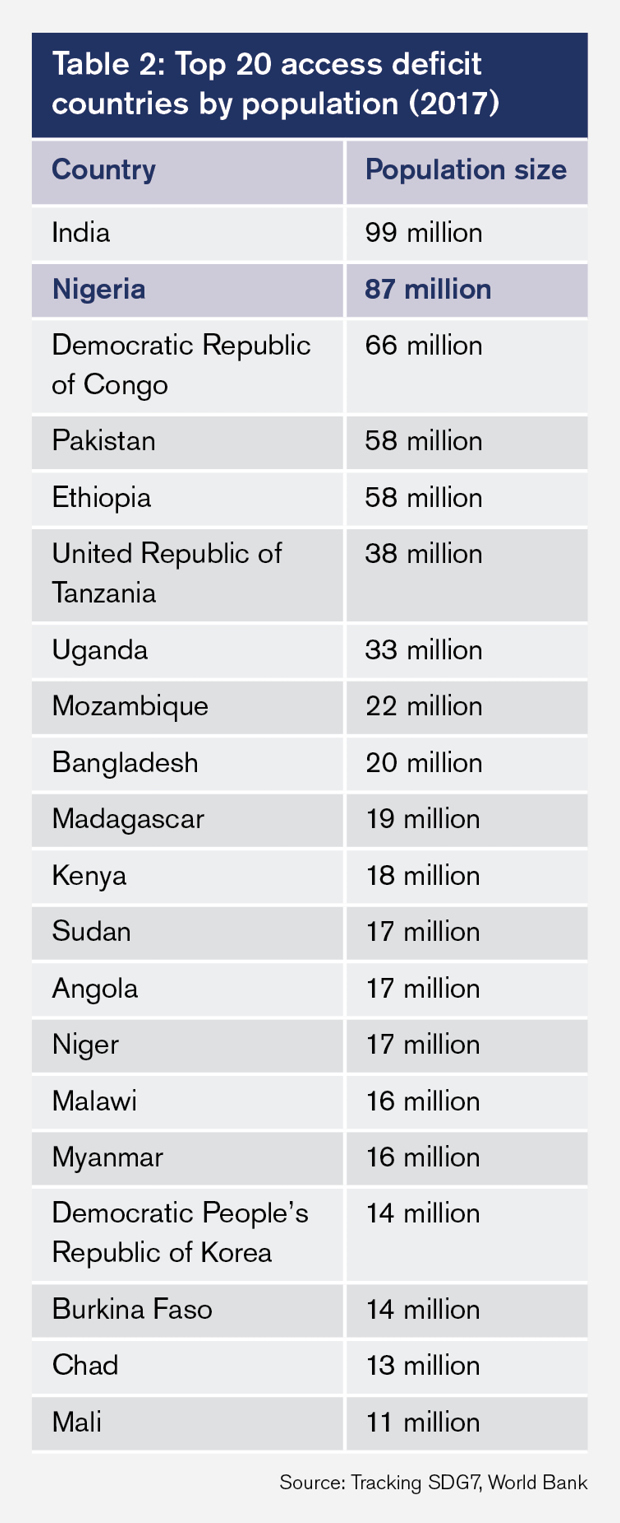

Similar to Kenya, beyond helping it reach its climate goals, boosting solar power in Nigeria will help the country bridge its large deficit gap. According to the Tracking SDG7 Energy Progress Report, Nigeria had the largest access deficit in terms of population globally behind India in 2017 and the highest across all of Africa (see Table 2).

Renewable energy is also set to bolster job creation in the country. According to a ‘job census’ report by Power for All, a non-governmental organisation, growth in the renewable energy sector is already having a positive spinoff as the sector’s workforce is now comparable with traditional power grids and utilities. The sector currently employs around 4,000 informal jobs compared to 10,000 employed across the country’s traditional energy sectors. Moreover, jobs in renewable energy are expected to grow by 100% in the next four years.

South Africa

According to South Africa’s Ministry of Energy, around 91.2% of electricity generation comes from thermal power stations whilst around 8.8% comes from renewables. This technology mix renders South Africa one of the top carbon emitters globally (see Table 3).

The release of the country’s long-awaited Integrated Resource Plan (IRP), approved and made public on October 18, 2019, has the potential to change this.3 The plan maps out the scale and pace of new electricity generation capacity to be commissioned until 2030 and has a strong focus on renewables.

The IRP provides for 14,400MW of new generation to come from wind, 6,000MW from solar PV, 3,000MW from gas, 2,500MW from hydro, 2,088MW from storage and 1,500MW from coal. Solar and wind alone is expected to make up 25% of electricity generation by 2030. The IRP also makes provision for the inclusion of nuclear power. The country’s Koeberg Power Station is expected to reach the end of its design life in 2024, and as part of the IRP, South Africa has made a decision to extend this. Given the long lead times, preparation will start now for new nuclear builds that will come online after 2030. Thereafter, modular nuclear power station stations will be built to replace the decommissioning of coal-fired plants.

As demonstrated, there is a strong focus on renewables in the plan with 48% of new energy capacity to come from wind, 20% from solar, 10% from gas, and 8% from hydro. Moreover, the private sector is expected to largely fill this gap, as there will be no more complex and expensive base load infrastructure projects that the country previously pursued. Indeed, upon the launch of the plan, energy minister Gwede Mantashe confirmed this when he noted that government urgently needed another 4,000MW installed as quickly as possible. As such, it is expected that more independent power producer bidding rounds will be launched.

Other countries

Beyond the top three economies, Ghana and Ethiopia have been identified as having significant renewable energy potential as well.

In February 2019, Ghana’s Energy Commission lodged its own REMP, setting out the blueprint for power production until 2030. Under the plan, Ghana aims to increase installed renewable capacity – which, under the classification, excludes hydropower projects greater than 100MW – from 2015 levels of 42.5MW to 1,364MW by 2030. To achieve this, the government plans to enact tax reductions; exemptions on import duties and value-added tax through to 2025 on materials, components, machinery and equipment that cannot be sourced domestically; and import duty exemptions on plant parts for electricity generation from renewables.

Turning to Ethiopia, despite its large energy potential, the country struggles to serve a population of over 100 million people and meet growing electricity demand, which is forecasted to grow by approximately 30% per year. Ethiopia’s Growth and Transformation Plans I and II seek to rectify this, outlining multi-year plans to transform the country into a middle-income country by 2025 and to starkly increase electricity generation, particularly through hydropower – which accounts for 70% of current power generation – but also through solar power and wind. Numerous tenders have already been released to help reach this target.

Sub-Saharan Africa’s smaller economies also present significant opportunities for investors. The five countries with the highest renewable energy investment as a percentage of GDP globally, for example, are all emerging or developing economies. From Sub-Saharan Africa, Rwanda and Guinea-Bissau make this list.4 Other smaller economies have also set renewable energy targets, demonstrating a commitment to the development of this sector. They include Cape Verde, Djibouti and Swaziland.

Risk advisory

From the continent’s largest economies to its smallest, it is clear that there is a focus on the development of renewable energy in Sub-Saharan Africa. Growth of this sector promises to not only plug the gap with regard to electricity generation, but to help the continent achieve its climate goals.

While the opportunities and indeed the challenges differ from market to market, investors should nevertheless recall some of the more generalised risks that they may face when investing in this sector in Sub-Saharan Africa.

These may include:

- A weak or underdeveloped regulatory environment

- Shifting energy policies under new regimes

- The creditworthiness of state-owned utility companies

- Corruption and/or political pressure

- Security threats in remote locations

- Lack of financing for projects

- Contestation over land

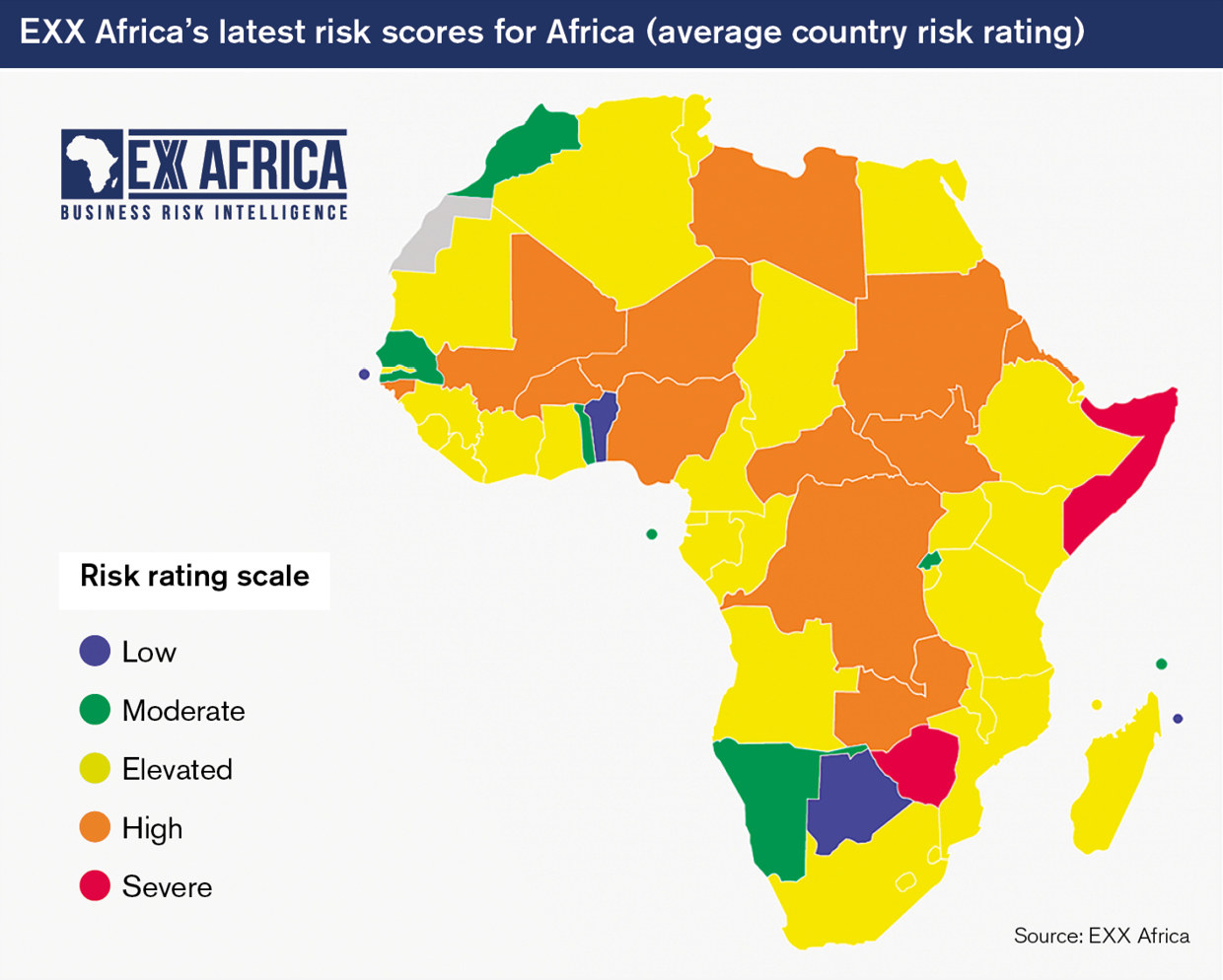

EXX Africa has developed a unique risk scoring system for 54 African countries that allows users to compare and contrast 10 individual risk perils for each country representing the macro political, economic, and security environment over a forecasted one-year outlook (see map).

Footnotes

- According to the US Power Africa Programme, despite having over 12MW of capacity, most days Nigeria only generates around 4MW of power.

- While Nigeria’s REMP provides for 20% by 2030, individual government ministries have promised 30% by 2030.

- The last such plan was the IRP 2010 promulgated in March 2011.

- The Marshall Islands, the Solomon Islands, and Serbia are also listed.

Please note this is a condensed version of a larger report on climate change, the UN Sustainable Development Goals and renewable energy from EXX Africa. www.exxafrica.com