In the aftermath of Donald Trump’s victory in the US presidential election, Asia Pacific states are turning their focus to the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), longed viewed as a rival deal to the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP).

International trade was one of the cornerstones of Trump’s successful campaign, in which he vowed to scrap ratification plans for the TPP, a 12-nation Pacific Rim trade deal.

He also pledged to either withdraw from or renegotiate US membership of both the North Atlantic Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and the World Trade Organisation (WTO).

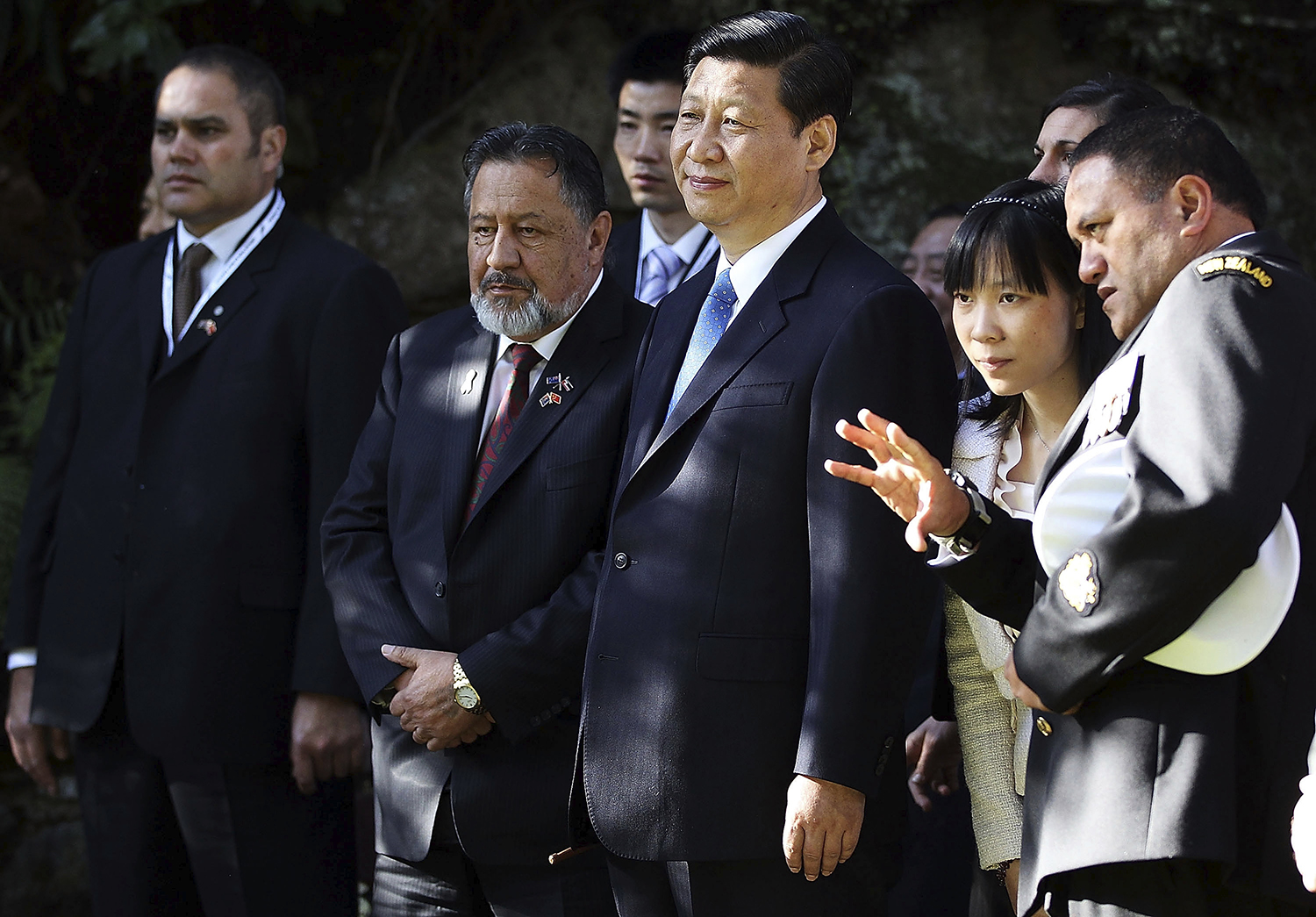

China, which is a member of RCEP but not of the TPP, is expected to push the agreement at this week’s Asia Pacific Economic Co-operation (APEC) conference in Lima, Peru and will be emboldened by the reaction of officials from countries such as Australia, Japan and Malaysia, all of whom have now thrown their lot in with RCEP.

Further to this, Chinese President Xi Jinping is also expected to advance Beijing’s agenda for the Free Trade Area of the Asia Pacific (FTAAP), a trade agreement which involves the 21 nations of the APEC, including the US.

The FTAAP has been billed in the past as an end-game for Asian trade: an amalgam of the RCEP and TPP deals. But China’s first priority will be sealing RCEP as soon as possible.

RCEP represents about 30% of global GDP and almost half the world’s population. It includes India and China plus Asean, Australia, New Zealand, Japan and South Korea but excludes the US.

With TPP off the table, it is the only megaregional trade agreement currently open to Asia Pacific countries, some of which were hoping to double up, as it were, by ratifying both.

RCEP takes command

Japan last week ratified the TPP in anticipation of a Hillary Clinton victory. Prime minister Shinzo Abe had hoped that by doing so, Japan could persuade the Democratic candidate to revise the populist anti-TPP stance she took on the campaign trail once she took office.

However, after Trump’s shock victory, the Obama administration has given up on the prospect of ratifying the TPP in the “lame duck” period before January. Japan is now turning its attention to RCEP – an agreement that his government had been relatively cool on before now.

“There’s no doubt that there would be a pivot to the RCEP if the TPP doesn’t go forward,” Abe told the Japanese parliament last week.

He is to visit the US en route to Lima in order to discuss Donald Trump’s stance towards Japan, which was often belligerent on the campaign trail. Trump has accused Japan, along with China, of manipulating its currency and thus damaging US trade prospects.

In Malaysia, minster for trade II Datuk Seri Ong Ka Chuan said that the country will now be turning its efforts to completing RCEP this year after Trump’s election.

“Now with the situation of the TPP, the focus will be on RCEP. We hope RCEP’s conclusion will offset a lot of the negative impact of the TPP. We will try to conclude the deal by December, but there has been some delay,” he said.

Meanwhile, Australia’s trade minister Steve Ciobo told the Financial Times this week that the country will also throw its weight behind the RCEP – even after prime minister Malcolm Turnbull pledged to continue the country’s alliance with the US after Trump’s election.

Ciobo said: “Any move that reduces barriers to trade and helps us facilitate trade, facilitate exports and drive economic growth and employment is a step in the right direction.”

Watered-down agreement

Those involved with RCEP had hoped to finalise an agreement by the end of 2016, but experts are sceptical as to whether this can be achieved.

Some of the issues stem from the lack of existing trade agreements between some member states, as well as the regional rivalries between some of the key members. In short, they are working from a lower base, and some nations feel they have more to lose.

CEO of the Asian Trade Centre Deborah Elms explained to GTR before the election results: “At the end you’re going to be opening up the dialogue partners to each other: India, China, Japan and Korea. That’s causing all sorts of anxiety. To expect them to be finished at the end of the year might be naïve.”

The general view is that, as with TPP, RCEP has been watered down with concessions in order to reach an advanced negotiating stage. It is viewed as a less sophisticated agreement than the TPP, mainly dealing with tariff removal rather than non-tariff barriers. However, these are still substantial.

“With RCEP, there are still tariffs to come down. Not in Singapore or Australia, but with, say, China. There were big tariff reductions to gain entry to the WTO in 2001, but there’s still more that can be done and there’s a question of what China would ultimately put on the table with RCEP. There’s also real challenges there in terms of India’s tariff regime,” Craig Emerson, former Australian trade minister tells GTR.

He adds: “I guess there was a higher level of ambition associated with the TPP when there were four countries involved. This changed when there were 12 involved, but who knows what the ambition for RCEP might be without TPP. If there’s no TPP, maybe there’s more ambition.”

If Chinese President Xi Jinping is serious about getting RCEP over the line before the end of the year, it may require further yield still. However, the symbolism would be clear: the US has abandoned Asia, the pivot to Asia is dead, and China’s influence over the region’s trading future is secured.

“If you think of how Obama framed the TPP: as the last chance for the US to pivot towards Asia and to have influence over trade in those countries, balancing the Chinese influence in that region. With Trump not ratifying the TPP, [Filipino President Rodrigo] Duterte changing his approach to China, it all shows that without the TPP, there is no pivot to Asia,” Andrés Delgado Casteleiro, an expert in international dispute settlement at the Max Planck Institute in Luxembourg, tells GTR.

The APEC Summit started on November 14 and runs until November 20. Many of the 21 respective leaders will be in attendance, including Russia’s Vladimir Putin, Barack Obama of the US and the inflammatory Rodrigo Duterte of the Philippines, who has vowed to fly to Peru via New Zealand so that he does not have to set foot on US soil.