While money is poured into projects along the land and maritime networks that connect Asia with Africa and Europe, and which make up China’s ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), questions are being raised about its progress and whether it is saddling fiscally weak countries with debt. Maddy White reports.

Since its launch in 2013 by Chinese President Xi Jinping, analysts have found it hard to measure the Belt and Road Initiative’s success, as its numerical targets, KPIs and formal membership protocols have not been clearly defined.

“Isn’t that a good thing if you are a Chinese strategist writing documents for the politburo? You want something which can’t fail,” Benjamin Charlton, senior East Asia analyst at Oxford Analytica, tells GTR.

With something as grand as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) – written into the constitution of the Chinese communist party in 2017 – keeping KPIs vague is best, says Charlton. The initiative can be compared with other high-level Chinese projects, such as the country’s AI strategy and its Made in China 2025 plan, which are both light on numerical objectives. “They’re really aspirational and one of the reasons for this is that nobody wants to be blamed if the targets aren’t met,” he says.

China continues to invest significant amounts of money into overseas infrastructure projects, including ports, railways and roads, all considered to be part of the BRI.

More than 125 countries and 29 international organisations have signed upward of 170 co-operation agreements under the initiative. The goods trade volume between China and countries involved in the initiative surpassed US$6tn from 2013 to 2018, with an average annual growth rate of 4%, while Chinese companies’ direct investment in countries involved in the BRI exceeded US$90tn in the same period, with an average annual growth rate of 5.2%, according to state-owned news provider China Daily.

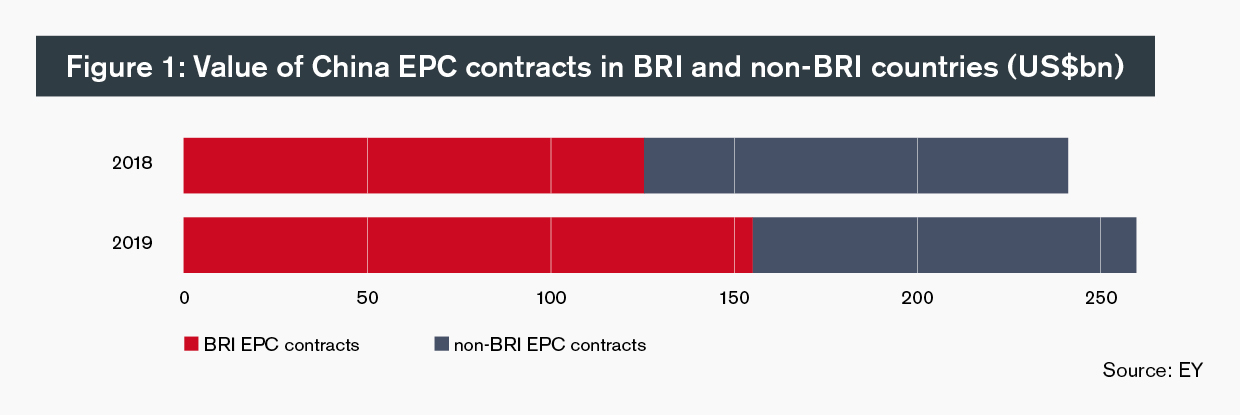

More recently, China’s overall outward direct investment amounted to US$117.1bn in 2019, down 9.8% on the previous year, according to China’s Ministry of Commerce and State Administration of Foreign Exchange. It does not reveal how much of this was allocated to BRI countries. Last year, the total value of newly signed China overseas engineering, procurement and construction (EPC) contracts increased by 7.6% to US$260.3bn, of which nearly 60% (US$154.9bn) were contracts signed in BRI countries.

Aboard BRI

Banks are seizing the opportunities brought about by the BRI. DBS Bank, for one, signed an agreement last year with Sinosure, China’s export credit agency, to provide credit insurance for its financing of BRI projects.

Lim Wee Seng, group head of project finance at DBS, tells GTR that the bank has “made steady progress since the agreement was signed last year. To date, we have successfully closed two projects with insurance provided by Sinosure, with another five project mandates in the pipeline.”

Both finalised deals are in Southeast Asia, comprising one transportation project and another industrial venture, costing approximately US$1bn apiece. DBS is providing more than US$200m of debt financing to the projects under Sinosure cover. Its five other development projects are mandated in the energy and power sector. He adds: “We have seen more project financing opportunities for BRI in Southeast Asia and South Asia, particularly in markets such as Indonesia, Vietnam and Bangladesh.”

Another bank that is making its mark on the BRI is HSBC, which says it arranged US$525bn of cross-border financing “involving China” between the start of 2017 and September 2019. “HSBC sees the BRI as a historic opportunity to improve economic connectivity globally. It is a counterbalance to economic unilateralism, showing the mutual benefits that stem from working together,” the bank says.

Elsewhere, governments are also strengthening their ties with China. Turkey’s sovereign wealth fund inked a US$5bn agreement with Sinosure to promote bilateral trade and investment as part of the BRI in March, while Etihad Credit Insurance (ECI), the UAE’s export credit agency, partnered with three Chinese financial institutions – Sinosure, the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC) and Bank of China – in a bid to boost non-oil trade and investment between the UAE and China last year.

Debt trap

However, fears of debt distress have dampened excitement over the BRI. The Hambantota International port in Sri Lanka saw the country’s government fail to repay Chinese loans to build the port, forcing it to agree in 2017 to lease the port for 99 years to China Merchants Port Holdings in return for US$1.1bn.

In July, Pakistan turned to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for a US$6bn loan with an immediate US$1bn disbursal to help it deal with its high debt-to-GDP ratio, which has escalated since the announcement of the BRI. In December, the Asian Development Bank (ADB) also came to Pakistan’s aid, approving US$1bn in immediate budget support to the country to shore up its public finances as well as a US$300mn loan for energy reforms.

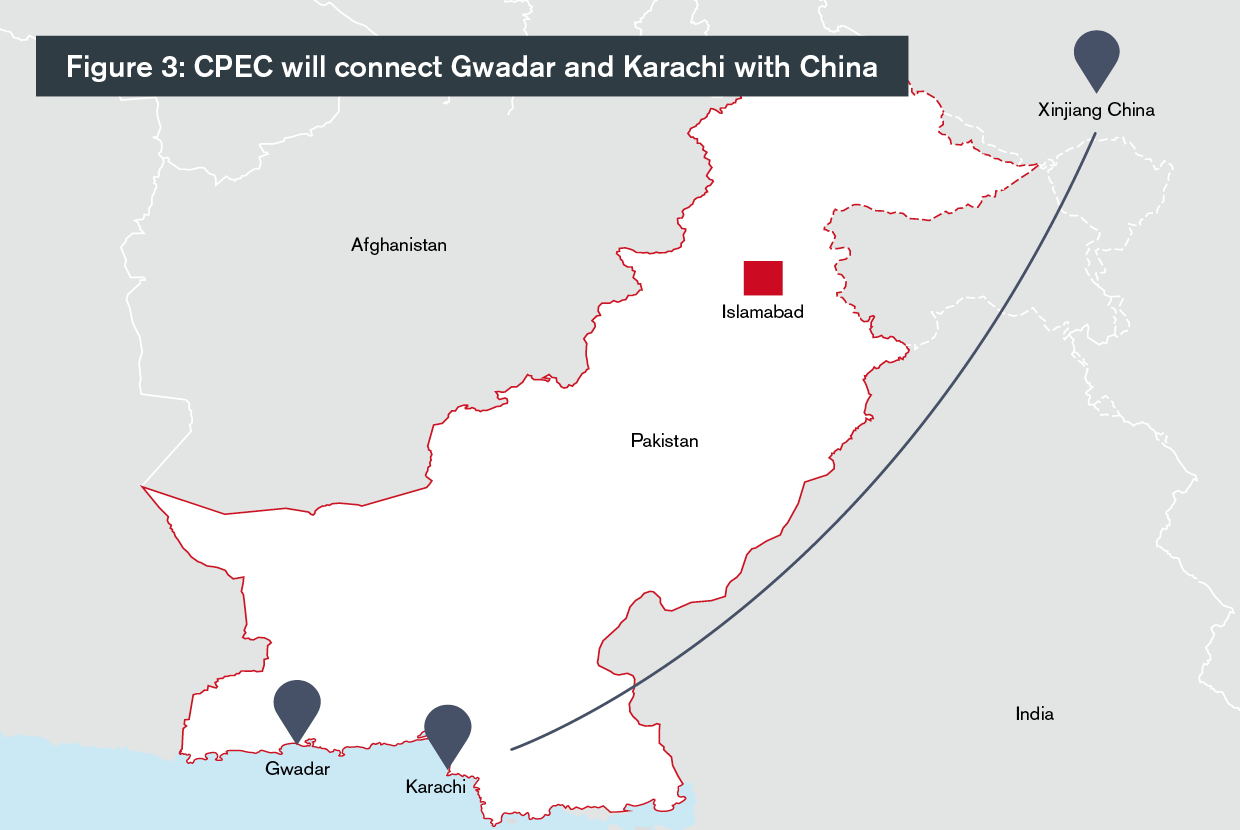

Pakistan plays a key part in the BRI. The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) is a collection of infrastructure projects that are under construction throughout the country, the value of which is estimated to be worth more than US$60bn. Transportation networks built under CPEC will connect seaports in Gwadar and Karachi with northern Pakistan, as well as China’s Xinjiang province. Beijing dismissed claims of BRI-triggered debt issues in Pakistan in November. “Debt incurred from CPEC stands at US$4.9bn, less than one-tenth of Pakistan’s total debt. I’m afraid the US is not bad at math, but rather misguided by evil calculations,” a post by a spokesperson for China’s Foreign Ministry reads on Twitter.

There are indications that some governments are becoming more savvy. China and Malaysia resumed construction on a BRI rail project in northern Malaysia in July, following a year-long suspension and after a deal was agreed to cut its cost.

The Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad cancelled the project after coming into power in 2018, as he followed through on a pledge to renegotiate or cancel “unfair” Chinese projects approved by his predecessor, Najib Razak. Last year, the two countries agreed to continue with the East Coast Rail Link at a cost of M$44bn (US$10.7bn), reduced from M$65.5bn (US$15bn).

Not all governments have been able to come to a favourable agreement with China, and some BRI projects lie incomplete, axed or at risk of falling apart. A US$275mn free-trade zone on the Kyrgyz-Chinese border that would see hundreds of hectares of land leased to Chinese firm One Lead One (HK) Trading for nearly 50 years to build and run a logistics and distribution area, as well as retail outlets, saw hundreds of people take to the streets in Kyrgyzstan’s Naryn region in February, demanding that the project be axed as they did not see it as beneficial to the local economy. Meanwhile, Myanmar dramatically scaled down its Chinese-backed Kyauk Pyu deep-water port project from US$7.3bn to US$1.3bn due to debt worries, and Sierra Leone scrapped a US$400mn airport plan outside of the country’s capital Freetown in October 2018 for similar reasons.

But China isn’t the only one saddling emerging economies with unsustainable debt, according to comments made by World Bank president David Malpass at a US debt forum in March. He said that the ADB is “pushing billions of dollars” into a fragile Pakistan, and that the African Development Bank (AfDB) was doing the same in Nigeria and South Africa. “We have a situation where other international financial institutions and to some extent development finance institutions as a whole, certainly the official export credit agencies, have a tendency to lend too quickly and to add to the debt problem of the countries,” he said.

Some say that loan terms are the key component in examining what debt a country can take on. Scott Morris, director at the US Development Policy Initiative and senior fellow at the Center for Global Development (CGD), a think tank, wrote in a CGD blog post that “as a leading creditor to Pakistan, China’s terms suggest that Pakistan’s bilateral loans as a whole are less concessional than those of the MDBs. And when it comes to private credit, a smaller but significant share of external debt, Pakistan faces very steep borrowing costs, relative to official sources: current 10-year bond yields average 11%.”

Covid-19 may cause delays

In the meantime, Covid-19, the novel coronavirus that originated in China’s Hubei province at the end of 2019, has spread around the globe, disrupting supply chains and trade. China’s Ministry of Commerce says that the BRI “may experience short-term delays from the Covid-19 pandemic, but its long-term momentum will be sustained”. The cause of any setbacks in BRI projects are likely to be a result of travel restrictions and border control, it adds.

“We expect infrastructure projects to be delayed due to weaker financial sentiment and supply chain disruptions, but strong demand and a pipeline of projects continue to point to a post-crisis rebound,” says Jangping Thia, manager of the economics unit at the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB).

Work on Sri Lanka’s port city Colombo project has been slowed by travel restrictions as Chinese workers have not been able to access the site, while those working on the Jakarta-Bandung rail line, a US$6bn high-speed rail route expected to be completed next year and largely funded by loans from China Development Bank, have been unable to return to Indonesia since the Lunar New Year holiday.

A report by law firm Baker McKenzie published in March says that the nature, pace and scope of BRI activity will be affected, both in the near and longer-term future. It adds: “Despite challenges to manufacturing and supply chain activity, the pace of digital BRI activity [from ICT companies to e-commerce platforms] has ramped up as have investor interest in Chinese tech companies and in the general healthcare industry.”

The pandemic might create a demand for more healthcare facilities along the BRI, says China’s Ministry of Commerce. “Once China has recovered from the situation, it might be able to offer a different sort of diplomacy by offering its medical expertise and supplies to countries that need it,” says Nicholas Ho, deputy managing director of Ho & Partners Architects Engineers & Development Consultants, whose firm has projects in BRI countries. He adds that: “In the long run, a few months’ delay is not going to stop an initiative like the Belt and Road.”