The boycott of Qatar by four Arab countries has put the whole region on edge. So far, the small gas-rich nation has proved resilient, writes Sanne Wass.

It was just another average Monday back in early June when Qataris first received the news that would soon cause panic across the whole nation: four of its Arab neighbours – Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain and Egypt – had cut the small gas-rich country off.

It meant closing all transport links with Qatar, including the country’s sole land border with Saudi Arabia, and all airspace to Qatari aircraft. The quartet gave Qatari citizens 14 days to leave their territory, and urged their own citizens in Qatar to come home.

Social media was soon flooded with videos of anxious Qataris emptying their local supermarket shelves for fear that stocks of food and water would run out. At the time, no one could imagine that Qatar, a country of 2.3 million people highly dependent on the import of food, would be able to sustain such an isolation.

But now, seven months later, as GTR goes to press, Qataris have woken up to a different reality. What started as just another Monday in June turned out to be the beginning of a new normal.

Of course the empty supermarket shelves quickly refilled. Qatar made rapid moves to stave off possible shortages, securing food and water provisions from countries such as Turkey and Iran. One anecdote involved a Qatari businessman planning to import 4,000 Holstein dairy cows via 60 flights to secure future milk supplies.

But the diplomatic crisis didn’t go away. The Saudi-led bloc continue to uphold their accusation that Qatar is supporting terrorism – the allegation that caused the row in the first place, and which Qatar continues to deny. Mediation efforts by various parties have as a result been deadlocked.

Meanwhile, Qataris have been forced to adapt to a new environment.

The immediate shock

The consequences of Qatar’s diplomatic isolation were quickly felt.

The boycott almost immediately prompted downgrades from ratings agencies, with Fitch, Moody’s and Standard and Poor’s all changing their outlook for the country from stable to negative.

A number of UK banks, including Barclays, RBS and Lloyds Banking Group, said in June they had stopped selling and buying Qatari riyal for retailers. Qatar’s stock market dropped 10% after the announcement. And, according to the country’s ministry of development planning and statistics, there was a 32% decline in passenger traffic into and out of Doha Hamad airport between May and the end of June.

By mid-September, Moody’s reported that negative foreign investor sentiment had increased Qatar’s financing costs and led to sizable capital outflows – in the vicinity of US$30bn.

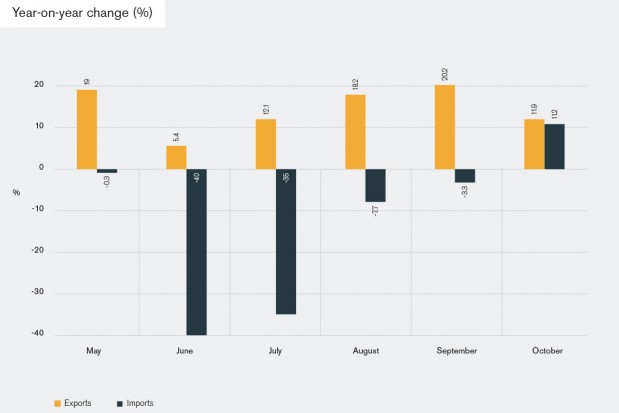

Qatari trade also felt an instant slump. Imports in June were down no less than 38% from May, and 40% compared to June a year earlier. At the time, the sharp drop was said to be an indication of how big a threat the boycott imposed to Qatar’s economy.

However, months later, the impact of the embargo on the small Gulf country is fading. Qatar, the richest country in the world measured by GDP per capita (according to the IMF, the 2016 GDP of a Qatari citizen was on average US$129,726), has so far been able to withstand the storm.

“The import drop in June was humungous, but after that it has been increasing rapidly. Qatar already recorded a year-on-year increase in its imports during October,” says Francisco Tang Bustillos, a Middle East analyst at IHS Markit.

October’s data showed an import growth of 11% from October the year before, and Bustillos expects this to continue into a “sizeable jump in import growth” in 2018 as compared to last year.

Exports from Qatar, the world’s largest liquefied natural gas exporter, continued to grow throughout the middle of the year, hardly affected by the crisis at all. In fact, the outbreak seemed only a good occasion for the state-run Qatar Petroleum to announce it would increase gas production by 30% from its current production rate to 77 million tonnes per year.

Bustillos points to the fact that Qatar is actually not very dependent on trade with the region. Exports to the four boycotting countries only accounted for 10% of Qatar’s exports in Q1 2017, whereas its main export destinations, Japan, South Korea, India, China and Singapore, made up more than 65% of its total exports.

The country’s top import partners before the crisis were the US, China, the UAE, Germany and Japan. Although the UAE was among them, the four boycotting nations together only accounted for a total of 16.4% of Qatar’s total imports in Q1 2017, according to IHS Markit.

Naturally those figures have been affected by the boycott: by Q3, exports to the Saudi-led bloc had dropped to 3.7%, imports to 3.6%. The UAE is no longer among Qatar’s top import partners.

But Qatar has managed to make up for the trade elsewhere. It was quickly able to establish alternative sources of food imports, while also enhancing domestic food processing. The same goes for materials for construction projects as Qatar prepares to host the FIFA world cup in 2022: organisers insist they have found alternate suppliers and that their plans remain unaffected.

“The good thing about Qatar is that it’s really flexible – it is not completely isolated and it has other trade partners,” Bustillos says.

India, for one, crept up to replace the UAE as one of Qatar’s top five import partners in Q3. The US, too, has taken on a more significant role: according to IHS Markit, October’s surge in imports came mainly from the US, at a massive 265% growth rate from the month before.

Other countries have equally stepped up for Qatar. According to statistics released by Turkey’s Aegean Exporters’ Association, Turkish exports to the small Gulf country increased by 90% in the first four months of the blockade. The embargo is also, ironically, rewarding the GCC’s biggest rival, Iran. According to Iranian Customs Administration’s official data, Iranian exports to Qatar grew by about 60% in the months after the boycott.

On the financial side, too, Qatar has been able to weather the worst consequences of the embargo – albeit at a steep price.

According to a report released by the IMF in October, the impact on Qatari banks’ balance sheets has thus far been mitigated by liquidity injections by the Qatari central bank and increased public sector deposits. The report also emphasises that Qatari banks are “proactively focusing on securing additional long-term funding for their operations”.

Moody’s estimated in September that Qatar pumped no less than US$38.5bn (equivalent to 23% of GDP) of its US$340bn reserve back into its economy and financial system in the two first months of the dispute. The central bank has from the start insisted it is committed to maintaining the stability of the Qatari riyal’s peg to the US dollar.

“In terms of financial stability Qatar is strong, stable and functional,” Raghavan Seetharaman, CEO of Doha Bank, tells GTR. “There is food price inflation, otherwise the rest is under control. The international community is recognising that Qatar is a resilient economy.”

The logistical nightmare

Regardless of Qatar’s resilience, those doing business there continue to face one strain in particular: logistics.

Saudi Arabia is the only access to the country by land, and, more importantly, the UAE’s ports play a crucial role in shipping routes to and from Qatar.

The port of Fujairah, for example, is the primary bunkering port for the Middle East, and ships trading with Qatar have now been forced to alter their operations in order to obtain fuel elsewhere.

Meanwhile, Jebel Ali port, just south of Dubai, handles more than a third of cargoes in the Gulf and, before the boycott, 85% of ship-borne cargo for Qatar, according to figures obtained by The Economist.

The diplomatic spat appears to have been an opportunity for neighbouring ports to grab some of the market share: the majority of Qatar’s supply chains are now being re-routed through ports in Oman, which has remained neutral in the crisis.

Qatar Navigation, a shipping conglomerate, for one, said in August it was moving its regional trans-shipment hub from Dubai to the Omani port of Sohar. Maersk Line also responded quickly to the conflict by dedicating a 10-day rotation container vessel service from the Hamad port in Doha to Salalah in Oman.

Qatar, too, has taken steps to help shipping companies circumvent the blockade. In September, it opened its new deep-sea Hamad port, allowing large container ships to go directly to Qatar rather than docking in the UAE to be transferred to smaller vessels.

Despite the various efforts, transporting goods to and from Qatar is undoubtedly proving practically more difficult: it is taking longer and has become more expensive.

For businesses on the ground, especially in the involved countries, this disruption is very real. Although there is no blanket ban in Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain and Egypt on doing business with Qatar, restrictions on the movement of goods, funds and people are making the performance of contractual obligations extremely difficult, if not impossible.

“If this is the new norm, it’s becoming untenable,” Borys Dackiw, head of Baker McKenzie’s Abu Dhabi practice, tells GTR. “For the first two or three months over the summer, businesses absorbed the cost or renegotiated some terms. They’ve allowed for some delays and acknowledged there’s a significant change in events. But now they are really facing a situation where this is longer term. Businesses are now having to think about how to adjust to it.”

This, he explains, involves looking at contract terms and the possibilities of renegotiating them, as well as reassessing counterparty risk and additional costs of transportation, insurance etc.

While Dackiw hasn’t yet seen breach of contract claims in relation to the crisis, that may just be a question of time.

“I expect that claims will start flowing pretty soon, particularly in relation to the large infrastructure projects where there is really a big squeeze on delivery dates and timelines – there will effectively be technical breaches of contract terms,” he says.

There is no doubt that if the crisis remains unresolved it could have much wider consequences for the region as a whole. The IMF has warned that although the spat so far has had “limited impact” on growth in the region, it “could weaken medium-term growth prospects” and “cause a broader erosion of confidence, reducing investment and growth and increasing funding costs” – not only in Qatar but possibly also the rest of the GCC. A protracted rift could also slow progress toward greater GCC integration, the IMF says.

It remains unclear what, if anything, will resolve the crisis, and mediation efforts have so far lacked progress.

Due to its political nature, experts that GTR spoke to for this article are cautious about putting a time frame on the crisis. “It will take a long time to resolve,” Dackiw says. IHS Markit’s Bustillos expects the dispute will last at least throughout 2018. One aspect they can agree on is that this is nothing but a small bump in the road: one that will not swerve Qatar off track.

Legal view: No ban on doing business with Qatar

Months after Qatar’s diplomatic isolation, the technicalities of the boycott are still not completely clear.

Unlike more formal sanctions regimes maintained by, for example, the EU and US, there has been no formal legislation passed by Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain and Egypt. The restrictions have instead been implemented through instructions given to executive government agencies.

This includes the countries’ harbours and airports: Qatari flagged or owned vessels and aircraft have been prevented from entering the territory of the four states, and vessels travelling to and from Qatar have been restricted from calling at their ports. The road between Saudi Arabia and Qatar has also been closed.

The exception to this is Egypt, which has not restricted Qatari vessels from its territorial waters or the Suez Canal.

Other restrictions imposed by the four states include those on the movement of persons and access to some Qatari websites.

What is worth noting is that trade with Qatar is not unlawful per se: the principal restrictions imposed by the quartet have so far been focused on modes of transportation rather than underlying trade or transaction, and it is in theory still possible to lawfully move goods to Qatar via a third country.

“Business carries on between Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Egypt, Bahrain and Qatar,” says Borys Dackiw, head of Baker McKenzie’s Abu Dhabi practice. “There is no ban on doing business. But business is much more difficult, it’s more onerous, it’s more costly, and logistically it’s a problem because of the disruption to supply chains.”

Added to this comes the risk of extended processing times of banking operations, a growing cost of insurance and the fact that face-to-face meetings have become difficult to arrange.

One area in which the countries have passed specific legislation is by updating their respective terrorist watch lists to include another 59 individuals and 12 organisations as Qatar-linked supporters of terrorism. In the absence of official instructions, however, it remains unclear what specific actions will be taken against those on the list or their connections.

“Further restrictions have been imposed on dealings with six Qatari financial institutions, requiring enhanced due diligence on transactions associated with them,” states Patrick Murphy, a Dubai-based partner at Clyde & Co, in a Lexology update in November. “However, there is no blanket ban on transactions with those financial institutions and it appears, for the moment, that UAE and Qatari financial institutions are in all other respects dealing with each other normally, including in remitting Qatari riyals.”

According to a client alert by Baker McKenzie, the increased know your customer requirements for dealing with these six banks comes with a risk that funds flows could be scrutinised more closely, and hence bring about the possibility of delays in the payments process.

There are also signs that the disruption is getting worse, explains Baker McKenzie’s Dackiw. Over the past few months, Qatar too has begun restricting the customs clearance of goods that are manufactured in Saudi, the UAE, Egypt and Bahrain.

“Qatar took the position that it will not allow the import directly or indirectly of any Saudi, UAE, Bahraini or Egyptian origin good, and we now know from what’s happening on the ground that Qatar has begun enforcing that position,” he says.