The newest iteration of supply chain finance is here. First pioneered in Germany, it is now catching the attention of corporates and their banks across Europe and beyond. But, as Jacob Atkins reports, it hinges on maintaining favourable accounting treatment.

The latest supply chain finance product on the market comes with a warning from some of its providers: don’t use it too much.

Post-maturity financing – also known as ‘payment with terms’ or by various brand names – emerged in the German-speaking market around three years ago.

Like standard supply chain finance products such as reverse factoring, it allows companies to improve their working capital by delaying payments to suppliers. But with post-maturity financing, there are a couple of twists.

First, unlike in regular buyer-led supply chain finance programmes, suppliers are not paid early and therefore are not effectively funding the buyer’s working capital by accepting a discount. They receive payment on the original invoice due date – and for the full amount.

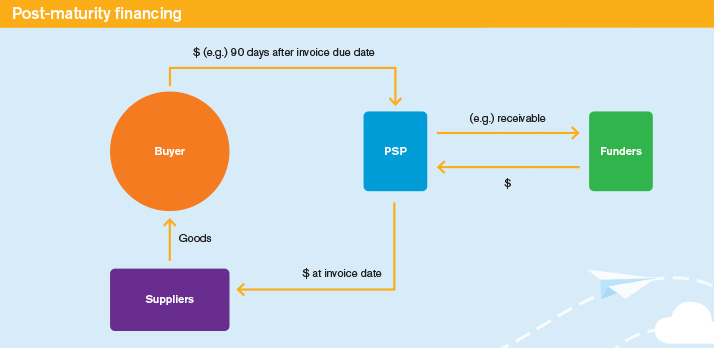

Second, the supplier is paid by a licensed payment service provider (PSP), which could be the programme provider, or a third party. After paying the supplier, the PSP issues a new receivable to the buyer, which must be repaid at an agreed date.

The structure is seen as innovative because the use of the payment service provider – as opposed to a bank – to pay suppliers means auditors are generally comfortable with the payment obligation to the PSP being classified as a trade payable or other liability, instead of debt.

A balance sheet with less reported debt can help companies secure cheaper borrowing and attract more investment.

“Positively speaking, it’s a flexible instrument,” says Alexei Zabudkin, chief financial officer of working capital marketplace CRX Markets, which offers the product. “You ramp it up quickly, and you ramp it down quickly, if need be.”

Post-maturity financing is also much faster to set up than a typical supply chain finance programme because suppliers do not need to be informed it is a quick win for treasurers and chief financial officers who need to hit working capital KPIs.

It took just a few weeks last year for Lufthansa to set up a post-maturity financing facility, according to cflox, the German fintech that provides the programme. At the end of last year, the airline had €258mn of liabilities under the programme, its annual report says, compared with €583mn for a traditional supply chain finance programme managed by CRX Markets.

“It took [Lufthansa] around six years to create those volumes on supply chain finance – it took them six to eight weeks to do the same with us,” says Ralf Kesten, cflox’s head of multinationals and partner management. The product has established a firm foothold in the working capital landscape of Germany and other German-speaking markets over the last three years or so.

cflox, which calls its solution cfloxpay, is widely credited with pioneering the product. It launched in 2020 after receiving a payment institution licence from the German financial regulator. Kesten tells GTR the company executed the equivalent of €15bn in supplier payments over the last 12 months.

It currently operates in 14 EU countries and will have around 150 active programmes by the end of the year. Demand is also gathering further afield in the region, with interest from companies in countries such as the UK, France and Italy.

“The average cost of improving the working capital for our buyer clients is lower than if they were working with a deferred payment solution provider only.”

Markus Schiffers, Orbian

Beyond Europe, supply chain finance platforms such as Orbian are rolling out programmes in Singapore and the US. Programmes vary in size from around US$20mn to the hundreds of millions.

At the core of the model is the use of the PSP, which creates a degree of separation between the corporate and the bank, allowing the programme’s value to be recorded as payables or other liabilities, which improves the company’s debt-to-equity ratio and similar balance sheet metrics.

But banks remain central players. Behind the scenes, they are active as funders, attracted to the structure by the speed at which it can be put in place and deliver returns. Funding models differ: some funders may purchase a receivable from the PSP; in others, the PSP refinances its exposure to the client.

Banks are also key drivers of market expansion, introducing the structure to their corporate clients. Participating institutions include Deutsche Bank, Commerzbank, Rabobank, UniCredit and Raiffeisen Bank International, according to the websites of platforms providing post-maturity financing. Funds and family offices can also invest in programmes.

A note of caution

Given the speed at which companies can implement the tool, it should be set for widespread adoption.

But some providers that spoke to GTR shared a similar caveat: although they are comfortable with the product, they prefer to offer it either in conjunction with, or as a stepping stone to, a regular reverse factoring arrangement – rather than as a standalone big-ticket programme.

Both CRX Markets and Orbian like corporates to combine post-maturity finance with other sources of working capital and, ideally, transition over time into a fully-fledged supply chain finance programme with the involvement of their suppliers.

“We consider this an add-on,” says Zabudkin. “We don’t consider this as a product that should be the only instrument in your working capital toolbox.”

That’s partly because a programme that buyers have established with the consent of suppliers is more stable, but also because of the way companies account for the product. “If you try to replace your bank debt with this” ratings agencies “will certainly smell something”, he adds.

A funder, speaking on the condition of anonymity, says their institution is cautious “not to rely too heavily on” the programmes despite the ease at which they can generate volumes, because of the risk that auditors could change their currently amenable view of the accounting classification.

Cflox, however, argues that the product works on a standalone basis and is a “huge market by itself”. “We see it as a separate product” that can be, but doesn’t have to be, combined with a traditional supply chain finance arrangement, Kesten says.

“There are different ways – supply chain finance, digital bills of exchange, innovative supply chain finance programmes – which help corporates [meet] their KPIs in very uncertain times.”

Investment-grade companies also need to bear in mind the opinion of ratings agencies. Tension has long characterised the relationship between supplier finance providers and the bodies that set credit ratings, who argue that non-disclosure of such financing essentially amounts to hidden off-balance sheet debt.

Most programme users have total repayment terms that fall within the 90-day period ratings agencies usually view as the upper limit before a trade payable may need to be classified as debt.

S&P Global Ratings, one of the big three agencies, deems any trade payable extended beyond that limit as having the characteristics of debt, and “usually view[s] payments that are settled beyond that timeframe as a form of financing”, it said in March this year.

Sam Holland, a London-based managing director at S&P Global Ratings, tells GTR that post-maturity financing does not strike him as having unique features that would warrant different treatment from any other forms of supplier finance.

“It might be a slightly new iteration, but it feels to me very similar to what we’ve been looking at for years,” says Holland, an accounting officer for Emea and Apac corporate ratings.

“I’m not saying that it’s definitely financing as far as reporting goes, but if we ran into it and we had the separate disclosure of that facility, we would likely consider it to have financing elements.”

David Gonzales, Moody’s Ratings

David Gonzales, senior accounting analyst at Moody’s Ratings, also views the differences between post-maturity financing and its established peers as small, but says “there’s a lot of judgment that goes into” determining whether payment with terms programmes should be allocated to trade payables or financing activity.

“I’m not saying that it’s definitely financing as far as reporting goes, but if we ran into it and we had the separate disclosure of that facility, we would likely consider it to have financing elements,” Gonzales tells GTR.

On the inclusion of a PSP between a funding bank and a programme user for accounting purposes, Gonzales says: “Effectively, it seems the argument is that they have a payable because somebody provided a service, and that service is financing. I understand that argument, but if your service is financing – that seems like a financing transaction.”

Moody’s and other agencies helped drive recent changes in accounting standards, which now require disclosure of supply chain finance in financial statements.

Post-maturity financing is widely viewed as meeting the threshold for disclosure under those rules.

To date, auditors have accepted the classification of post-maturity financing liabilities as payables rather than debt.

“It is always going to be at the discretion of the auditor of the particular customer at any one time,” says Matthew Hatton, head of product innovation at supply chain finance platform Traxpay. “But as each auditor agrees with us [that the programmes are not debt], then we’ve got more of a track record.”

Traxpay has added a further innovation to the post-maturity landscape by incorporating digital bills of exchange as the underlying payment instrument, the use of which has been eased by the Electronic Trade Documents Act in England and Wales. Bills are raised by buyers and purchased by investors, who then fund payments to suppliers.

Amounts owed under digital bills of exchange are also counted as trade payables, Hatton says. Initially the concept was a “hard sell” to corporates and banks but the product is “really picking up momentum”, particularly as more jurisdictions bestow legal recognition on digital bills of exchange.

SCF+

For now, post-maturity financing has earned its place in the supplier finance product suite – widely considered the fastest-growing area of trade finance.

Schiffers of Orbian says the platform has set up its offering so that companies can easily use payment with terms and regular supply chain finance simultaneously, which he says 50 to 75% of customers currently do.

This is attractive to funding banks because their investment can be deployed in either traditional supplier finance or post-maturity finance, while maintaining the same process and risk profile.

The hybrid model benefits corporates whose supply chain includes companies that don’t want to participate in supply chain finance – and have the negotiating power to refuse. Schiffers also says it is cheaper: “The average cost of improving the working capital for our buyer clients is lower than if they were working with a deferred payment solution provider only.”

Companies also have the option of deploying post-maturity financing on top of an existing supply chain finance structure. In the existing programme, a buyer would have to pay the financial institution that has already paid its supplier early, for example, after 90 days. But with a post-maturity add-on, the PSP steps in and repays the financial institution, and then creates a new invoice for that service, effectively extending the payment terms a second time.

Schiffers says that for transparency reasons, Orbian would typically only facilitate that structure if the original programme was being run by another platform.

The option is an example of the experimentation that the flexibility of post-maturity financing invites. But it remains to be seen if the product will become a permanent fixture in the working capital landscape.

This article was amended on November 10, 2025. The original version reported that Orbian provided a supply chain finance programme for Lufthansa. This has been corrected to show that CRX Markets provided the programme.