Invoice financing has grown dramatically in the last two decades, developing into a thriving ecosystem of banks, fintechs and institutional investors. But after a string of high-profile company collapses and market exits, can investors be sure their funds are safe?

This article first appeared in GTR‘s Q4 2025 magazine.

The supply chain finance (SCF) market grew rapidly in the wake of the 2008 global financial crisis. As a product, it promised investors a steady rate of return in a low or zero-interest rate environment, and numerous technology-driven platform businesses stepped into the market alongside established bank lenders.

A 2017 Oliver Wyman report said growth was so strong between 2010 and 2014 that market revenue from SCF had already surpassed that of traditional trade finance, standing at around US$24bn per year, and was expected to accelerate further as solutions became more sophisticated.

When applied well, the product makes sense for all participants, the report noted, bridging the gap between suppliers seeking payment as quickly as possible and buyers wishing to extend their payment terms.

Today, global volumes are still growing, up 8% in 2024 compared to the previous year, according to BCR. The total volume of programmes last year stood at nearly US$2.5tn, it says, albeit with a slight slowdown in growth in Europe and the Americas as the market matures.

But the off-balance sheet nature of SCF programmes has attracted scrutiny from authorities and ratings agencies, concerned that it could be used as a tool for obscuring debt, and the sector is no stranger to scandal.

The infamous collapse of Greensill Capital in 2021 shone a spotlight on the riskier forms of SCF, leaving investors facing heavy losses. More recently, the bankruptcy of First Brands Group left investors exposed to billions of dollars of the company’s debt. In the interim, a handful of non-bank providers have exited the market.

Companies managing these programmes have numerous tools for mitigating risks, from due diligence to technology to insurance. But what can external investors or funders do to ensure they are protected?

First Brands, factoring and a US$12bn black box

The risks around invoice financing have again been thrust into the spotlight following the downfall of First Brands Group, an Ohio-based supplier of auto parts.

First Brands and a complex network of group companies attracted vast sums of financing from a diverse pool of investors, making use of both receivables and payables finance programmes as well as a range of inventory and asset-backed lending facilities.

As its debt grew, the company launched a major refinancing effort in July, but this process was paused the following month when potential lenders insisted on further due diligence.

By late September, First Brands had filed for bankruptcy protection in a Texas court. Court documents revealed debts of almost US$12bn, a significant part of which was accrued through off-balance sheet instruments.

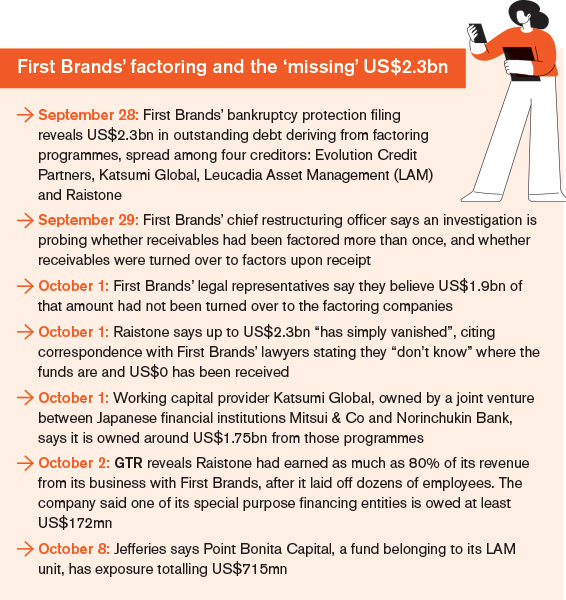

Filings revealed First Brands companies had built up a staggering US$2.3bn in factoring liabilities, where receivables are purchased by third parties that later collect the sums due.

A group of creditors also have over US$800mn in exposure to SCF programmes, where lenders would purchase debt generated from First Brands sales and purchases. Asset-based loans, such as inventory financing facilities make up much of the remaining funds owed.

Again, concerns have arisen over the integrity of those programmes.

In the case of the factoring liabilities, court filings revealed that an independent committee is investigating whether certain receivables had been factored more than once, and whether receivables had actually been turned over to third parties when received.

The investigation is also probing whether inventory pledged to one lender, Evolution Credit Partners, had been commingled with collateral securing a separate facility. As of press time, the investigation is ongoing, no wrongdoing is alleged, and the company did not comment when contacted by GTR.

Many of the investors in the First Brands SCF facilities are special purpose vehicles or subsidiaries used by banks and asset managers to deploy capital. Often, facilities were originated by third parties such as Raistone, a US-headquartered working capital platform, before being distributed to the investors.

US-based working capital provider Katsumi Global, which is owned by a joint venture between Japanese financial institutions Mitsui & Co and Norinchukin Bank, told the court it is owed as much as US$1.75bn from unpaid receivables – part of the outstanding US$2.3bn in factoring liabilities.

Katsumi served as the buyer representative and servicer for receivables purchases, acting “on behalf of a number of other investors”, its lawyers said during a hearing in early October. Bank ABC and ING Belgium each said in separate filings they purchased rights to certain receivables from Katsumi.

Separately, Point Bonita Capital, a fund belonging to Jefferies trade finance arm Leucadia Asset Management, has disclosed it has US$715mn in exposure arising from First Brands receivables.

O’Connor, a private credit firm owned by UBS, is owed upwards of US$116mn for supply chain finance investments originated by Raistone, bankruptcy filings show. The Swiss bank’s overall exposure to First Brands, across various entities, is more than US$500mn.

Raistone also said it has exposure of its own, including a portion of the outstanding US$2.3bn in factoring liabilities. The company said in court filings it is “owed no less than US$172mn” from those facilities. Raistone, which GTR revealed earned as much as 80% of its revenue from First Brands, has since laid off more than half of its employees.

Raistone also said it has exposure of its own, including a portion of the outstanding US$2.3bn in factoring liabilities. The company said in court filings it is “owed no less than US$172mn” from those facilities. Raistone, which GTR revealed earned as much as 80% of its revenue from First Brands, has since laid off more than half of its employees.

As of press time, it is unclear what proportion of the debt is recoverable. But an emergency motion filed by Raistone, which argues the court should appoint an examiner to investigate the whereabouts of funds from factoring programmes, says up to US$2.3bn “has simply vanished”.

Court filings include an email exchange between lawyers representing Raistone and First Brands in the wake of the bankruptcy filing.

Raistone’s lawyers ask two questions: whether the company “actually received US$1.9bn (no matter what happened to it)”, and how much has been transferred to segregated accounts opened to protect factoring creditors’ funds.

“#1 – we don’t know,” First Brands’ counsel replied. “#2 – $0”.

Greensill, Credit Suisse and the Finma files

The First Brands saga came just over four years after the infamous collapse of London-headquartered Greensill Capital. After the company filed for insolvency in March 2021, authorities in Switzerland launched a thorough probe into the company’s relationship with its largest financial backer: Credit Suisse.

Credit Suisse opened its first Greensill fund in 2017. In short, buyers would approve an invoice and Greensill would purchase the resulting debt from the supplier. That receivable would be transferred to a special purpose vehicle that issued notes, which were in turn bought by the Credit Suisse fund.

The bank went on to launch three more Greensill funds, and by 2020 had invested around US$10bn in securitised receivables originated by the company.

But by then, concerns were growing over the nature of some transactions, concentration risks within the portfolios of receivables and pressure from German regulators.

Insurers became unwilling to renew policies, and when cover worth billions of dollars from Australia’s Bond & Credit Company expired in March 2021, the writing was on the wall. Credit Suisse froze its funds and Greensill soon filed for insolvency.

Credit Suisse would later suffer its own downfall, with further scandals resulting in a loss of investor confidence and mass withdrawals of funds. The bank was subject to an emergency takeover by historic rival UBS.

Documents released to GTR by London’s High Court in July this year reveal fresh details of how the two companies’ fates became intertwined and – crucially – how investors were expected to assess the underlying risks associated with Greensill’s business model.

The documents comprise a near 500-page report completed in July 2022 by external law firm Wenger Plattner, as well as a subsequent ruling from the Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority (Finma) on potential breaches of conduct by Credit Suisse.

“The issue of future receivables was only rudimentarily clarified by the bank with external lawyers. When the SCF funds were launched, there was no discussion of the issue of future receivables.”

Wenger Plattner

The report from the law firm explains that when the Credit Suisse funds invested in Greensill-originated receivables, the “basic idea” was to offer investors returns despite the low prevailing interest rates at the time.

However, it detailed several “problem areas” with the SCF funds.

One “particularly noteworthy” problem area was future receivables, where financing would be provided against the expectation of future business between a buyer and supplier. The first programme explicitly including such arrangements was launched in September 2018.

The Wenger Plattner report analysed the extent to which Credit Suisse staff had oversight of the future receivables being originated and securitised by Greensill.

Wenger Plattner said contractual documentation included no uniform specifications “as to the degree of certainty with which there must be an expectation of realising the future receivable” for it to be sold to the Credit Suisse funds.

Legal and economic risks were not mentioned in fund documents, it said, and the issue of future receivables “was only rudimentarily clarified by the bank with external lawyers”.

The report added there was no discussion of future receivables internally after the SCF funds had been launched, although the bank’s portfolio managers “acquired a certain level of risk awareness regarding future receivables” over time.

However, they “had no knowledge of the proportion of future receivables in the funds until the SCF funds were closed”, it said.

Qualified investors and due diligence

Finma’s ruling was damning for the bank. It concluded that while the funds were operational, Credit Suisse’s portfolio management had only “limited understanding” of future receivables, and that although doubts were raised internally, these “were not taken seriously”.

In one example cited, a Credit Suisse employee expressed concerns over US$300mn provided in financing to a company whose revenue was only US$200mn. The employee said they doubted insurance cover would be valid if the expected receivables turned out to be fraudulent.

Finma also found that Credit Suisse did not know what proportion of securitised notes related to future receivables. It says that for the SCF fund, this figure turned out to be around 30%.

“For several programmes, the bank was unable to state whether ‘future receivables’ were permitted or not, either because this was not clear from the definition of ‘receivables’ in the programme documentation or because the programme documentation was not available,” the regulator said.

“Credit Suisse Asset Management must have been aware that the investors could not and did not carry out any due diligence. The investors rightly trusted that CSAM would fulfil its duties as the asset manager of the funds it had formed.”

Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority

The regulator also addressed whether investors should – or could – have known about the underlying risks.

Finma cites information provided by Credit Suisse, in which the bank argues the fund prospectuses made clear it would not carry out any due diligence or monitoring regarding the underlying obligations. This task, the bank said, was performed by Greensill.

The bank also pointed out that the funds were intended only for qualified, professional investors. This requirement, it argued, meant those investors “should have carried out their own due diligence”.

But according to Finma, Credit Suisse “repeatedly failed to fulfil its duty of loyalty, due diligence and information… particularly in relation to investors”.

Even if it had been clear to investors that Credit Suisse would not carry out due diligence or monitoring, in particular in relation to the obligors selected by Greensill, the bank “should not simply have relied on Greensill under its fiduciary… duties”.

“The bank should have initiated its own checks to limit its own risks,” Finma said. “Its argument that the investors in the SCF funds were qualified or professional investors and that they had to carry out their own due diligence was paradoxical.

“CSAM [Credit Suisse Asset Management] must have been aware that the investors could not and did not carry out any due diligence. The investors rightly trusted that CSAM would fulfil its duties as the asset manager of the funds it had formed.”

Market exits and further losses

The First Brands and Greensill cases are extraordinary in terms of scale, but the past year has seen other failures in the wider SCF market and subsequent difficulties in recovering investor funds.

In December 2024, UK-headquartered invoice financing provider Stenn had been placed into administration following an application by HSBC Innovation Bank.

Stenn’s administrators said the company employed over 200 people globally, and had deployed more than US$10bn in capital across over 70 countries since 2016. At one point it was valued at US$900mn.

But HSBC alleged in court filings that after investigating potentially suspicious transactions, it found Stenn had received funds from companies with slightly different names to the investment-grade firms named on invoices.

As of press time, administrators are continuing to probe Stenn’s affairs and assess potential returns to creditors, while the UK’s accounting regulator has launched an investigation into the company’s auditors.

Companies House filings revealed a potential shortfall in realisable assets totalling nearly US$200mn.

In March 2025, non-bank receivables finance Artis Finance also entered administration. Artis was founded in London in 2020 and provided origination and loan servicing, while its subsidiary Artis Loanco 1 – which also filed for administration – provided the financing.

A report filed by Artis’ administrators in April said that prior to its insolvency, the company launched an internal investigation into “alleged misrepresentation in information and reports historically prepared by [Artis Loanco 1]” and provided to noteholders.

Artis believed the alleged misrepresentation meant the true performance of its loan portfolio, including certain financial covenants, “may have been historically incorrectly reported as being met”, the report says.

The administrators’ report says little recovery is expected. US Bank has a fixed charge over Artis Loanco’s shares, but administrators say they do not believe it will recover any funds through this security.

The report adds Artis’ records show prepayments with a book value of around £133,000, but says these appear to be “largely accounting entries and no realisations are expected”. Intercompany debts with a book value of around £2.7mn also likely have no realisable value, it says.

Staying close to the trade

There are numerous differences between the failures of First Brands, Greensill, Stenn and Artis, but each involves at least one non-bank funder or platform using invoice financing as a means of generating returns for external investors.

For Baldev Bhinder, managing director of Singapore law firm Blackstone & Gold and an expert in trade finance litigation, the risks inherent in this model stem from the disconnect between the funder and the origination of the receivables.

“I suspect the focus appears to be more on the perception of a due receivable, rather than the trade from which it arises,” he tells GTR.

“The portfolio is done on a volume basis, sometimes turbo-charged by tech or wrapped with credit insurance, but there appears to be insufficient focus on the trade aspect of it. How the invoice funder selects and tests the veracity of the invoice against the trade is critical.”

Risks such as double financing, over-invoicing and carousel trades – where companies collude to generate invoices and obtain financing without a genuine underlying trade – can be “amplified where investors don’t have a sense of how close the originator is to the actual transaction”, the lawyer says.

“If you were to go to a bank and ask for an uncommitted trade loan, that bank would do its due diligence,” he says. “They would look at the supply chain; who you are buying from, who you are selling to, how long you have been in this business for and whether the commercials make sense.

“With invoice financing, there can be a blinkered approach towards the almighty invoice. People might forget that without an actual physical trade, liquidity doesn’t flow through the chain to ensure payment of invoices.”

Bhinder suggests random sampling of invoices, carried out by investors on a frequent basis, could help identify some instances of fraud – for instance, where a real company is named on an invoice but denies any knowledge of the transaction – provided there is no collusion between parties.

“With invoice financing, there can be a blinkered approach towards the almighty invoice. People might forget that without an actual physical trade, liquidity doesn’t flow through the chain to ensure payment of invoices.”

Baldev Bhinder, Blackstone & Gold

Other invoice financing providers address this issue through the business model itself.

Matt Wreford, outgoing chief executive of supply chain finance at FIS Supply Chain Finance, formerly Demica, says the vast majority of wrongdoing in invoice financing “drops into one box, which is where the business model is intermediation”.

“The most granular information doesn’t pass through all the way to the end investor, and there’s a very high motivation for yield,” he tells GTR.

For Wreford, investors should consider whether the funder is in direct contact with the borrowers. In FIS’ case, its platform facilitates transactions between international banks and their existing clients, while automating the flow of data.

“Unlike Greensill or Stenn, this means the funder is able to conduct due diligence directly with the end customer. That’s fundamentally important, because that way they’re not relying on information passing through the platform for due diligence. They are able to conduct their own checks,” he says.

“That’s very different to a scenario where a private credit investor is financing a company it doesn’t have a relationship with. Nearly all of the invoice fraud that has taken place in the market is in that category.”

Balancing risk, technology and cost

Technology is playing a growing role in managing the risk that the transactions underlying invoice finance arrangements are fraudulent in nature.

Wreford says FIS is able to connect to borrowers’ ERP systems, meaning information on every invoice and receivable is made available to the funder, as well as their cash collection accounts.

This effectively stops companies from reissuing fake invoices once they reach maturity, because the ERP system would show a spike in dilution. Tracking cash collection accounts would show significant deviations between funds being received and the value stated in invoices, Wreford says.

“If a borrower was intent on committing invoice fraud, they wouldn’t sign up for a platform that is taking a real-time feed out of the ERP, so as a funder you avoid adverse selection,” he adds.

“A fund might have assets under management of, say, a billion dollars circulating across one or more platforms – but if just one platform were to lose US$30mn, it could go out of business and spiral into bigger losses.”

Neil Shonhard, MonetaGo

Neil Shonhard, chief executive of fraud prevention tech firm MonetaGo, says invoice finance investors are also showing increasing interest in trade registries, which collect and analyse data from invoices and trade documentation to detect attempts at fraud. Registries built by MonetaGo are already in use in several markets, including Singapore and India.

“It’s quite common for funds to come to us and say invoice financing platforms should have these solutions embedded in them,” he tells GTR.

“A fund might have assets under management of, say, a billion dollars circulating across one or more platforms – but if just one platform were to lose US$30mn, it could go out of business and spiral into bigger losses.

“A fund also wants to see extra security measures on the receivables subject to financing, because they’re answerable to their investors.”

Different kinds of registries can be useful in various ways, Shonhard says.

Trade registries can be used to detect duplicate financing attempts, where the same documents are presented to multiple lenders, and can enable confirmation that a receivable has been assigned.

Collateral registries create a security interest but without addressing the individual transaction documents financed.

“Additionally, many countries have implemented e-invoicing for VAT purposes, and these registries can be used to authenticate the underlying invoices submitted to lenders for financing, as fraudsters are unlikely to pay VAT on a fabricated invoice,” Shonhard says.

Blackstone & Gold’s Bhinder agrees that integrating technology into a programme can be effective, but warns it adds to the cost of what is already a relatively low-margin product.

“These ideas are great, but ultimately, who’s going to bear that cost?” he says.

In MonetaGo’s case, registries are ultimately targeted at the national or international level, meaning costs would likely be absorbed by governments and/or bank users.

“Of course everyone is driven by cost,” Shonhard says. “But the way we see it, the question is what would a bank or an investor pay to de-risk their book in any one country, corridor or market segment? Or for a government, what is the economic value created by de-risking an ecosystem?”