South American countries rich in critical minerals may offer lower levels of political risk and resource nationalism than other emerging markets with large reserves, fresh research has suggested.

Risk consultancy Verisk Maplecroft found that nations in the region have “comparatively lower resource nationalism risk”, meaning South America could be “key” to the West’s restructuring of its critical minerals supply chains.

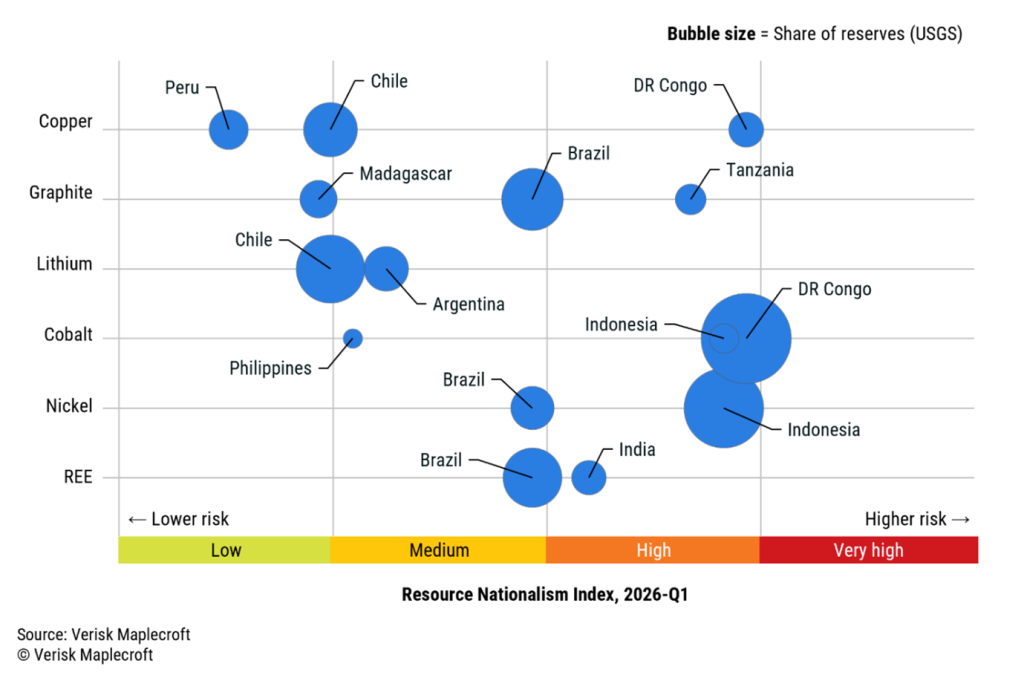

The firm’s findings draw on Maplecroft’s political risk data and resource nationalism index, which measures government control of economic activity within the extractives sector.

It evaluated 10 emerging markets with major reserves of cobalt, copper, graphite, lithium, nickel and rare earth elements: Argentina, Brazil, Chile, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), India, Indonesia, Madagascar, Peru, the Philippines and Tanzania.

While the DRC, Indonesia and Tanzania are all within the global top 20 highest-risk environments for resource nationalism, Peru, Chile and Argentina are much lower risk.

As many western nations take steps to reroute their supply chains away from China by building up domestic capacity and creating strategic alliances with other countries, determining which markets provide “the greatest policy certainty and political stability” for supply chains is vital, Maplecroft said.

The Trump administration, for instance, recently announced Project Vault, a supply chain security initiative – backed by the Export-Import Bank of the United States – between the US government and several private companies to store raw materials in facilities across the nation.

The UK has also vowed to reduce its dependency on China via UK Export Finance’s Critical Goods Export Development Guarantee, and the UK business secretary noted this month that a critical minerals alliance between major world economies “makes sense”.

Jimena Blanco, Verisk Maplecroft’s chief analyst, said the “distribution of risk” sets South America apart, and could explain “the intensifying US and EU focus” on the region.

South America has abundant reserves of many of the resources deemed critical by many countries. The Lithium Triangle, which spans Argentina, Bolivia and Chile, contains around half the world’s lithium resources, while Chile and Peru produce over a third of global copper.

“South American producers consistently combine large endowments of tech-critical minerals with comparatively moderate levels of resource nationalism and political risk,” Blanco said.

Simon Wolfe, co-founder and managing partner at geopolitical advisory firm Marlow Global, told GTR that on balance, “South America is a historically better venue for critical minerals investment”.

Jurisdictions in the region have “reliable legal systems, the rule of law, established mining frameworks, and long track records of hosting international operators”, he said.

“Critical is the ability to enforce contracts and repatriate capital. Asset seizures common in other regions are rare in South America.”

This is vital for long-term mining operations without an immediate return on investment. Riskier countries include the DRC, Wolfe said, where “armed conflict disrupting cobalt and copper operations, unpaid arbitration awards and governance challenges … make any long-term planning a gamble”.

He also cited Indonesia, whose “export bans and processing mandates have blindsided investors more than once and continue to pose problems”.

For the US, Latin America presents a clear nearshoring opportunity, Olena Borodyna, senior geopolitical risks advisor in the global risk and resilience team at think tank ODI Global, told GTR.

“Latin America was represented by countries including Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil and Peru at the recent US 2026 Critical Minerals Ministerial,” she said, referencing the US’ hosting of ministers from more than 50 countries to discuss how to reduce reliance on China.

“The region’s engagement is reflected in both diplomatic and financial terms,” she said, noting the recent US$565mn financing agreement with Brazilian rare earths miner Serra Verde through the US International Development Finance Corporation.

This is “a sign that the second Trump administration takes competing with China in the region very seriously”.

Less risky, but not safe?

Despite these signals from the US, Borodyna said “political and economic factors mean that Latin America’s potential in natural resources and other sectors does not always translate straightforwardly into investment”.

“It remains to be seen how US intervention in Venezuela and its broader regional policy translates into relationships with various governments on the continent and what this may mean for political risks for US investment,” she said.

For the EU, it is important that investments follow trade agreements like the Mercosur deal, she added.

Wolfe also pointed out that “less risky than the alternatives is not the same as safe”.

“Resource nationalism is picking up across the whole region. Chile now requires state majority stakes in new lithium partnerships. Bolivia has effectively nationalised its lithium sector,” he said.

“Argentina has taken the most investor-friendly path with RIGI [Incentive Regime for Large Investments], which offers 30 years of fiscal and regulatory stability, but the country still carries baggage from decades of policy reversals.”

Community opposition to mining is also growing in Chile and Peru, Wolfe added.

For banks and investors, the opportunity is “significant”, but companies must get to know the operating environment in each jurisdiction rather than relying on a risk rating, he said.

“Success will depend on integrating geopolitical foresight, resource nationalism and political risk assessment to delineate the clearest pathway to building resilient, western-aligned critical mineral supply chains,” added Maplecroft’s Blanco.