There is a new battleground in Iranian sanctions evasion. In 2025, for the first time, US enforcement actions targeted companies accused of blending Iranian and Iraqi oil to disguise its origin, and warned some of this cargo is being held in floating storage. A first-of-its-kind investigation by GTR, Blackstone Compliance Services and Pole Star Global reveals the extent of these practices and the risks they pose to the oil trading market. John Basquill reports.

Back in December 2024, Babylon Navigation DMCC had just paid US$33mn for a 2005-built suezmax, bringing its fleet of tankers to 10 vessels.

The company was described that month in a shipping industry report as “one of many fast-growing vintage tanker players” in the UAE.

But by the following September, Babylon’s fate had changed: it had caught the attention of the US government. The Treasury’s main sanctions body, the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC), issued a notice alleging that the company was part of a sanctions evasion network overseen by Iraqi-Kittitian businessman Waleed al-Samarra’i.

Al-Samarra’i, OFAC said, had used the network to generate a “conservative estimate” of US$300mn for the Iranian regime, primarily by selling oil marketed as solely Iraqi in origin but blended with Iranian crude.

Babylon was responsible for handling logistics and shipping, while another al-Samarra’i company, Galaxy Oil, acted as the “main trader of [his] energy products on the global market”, the authority said.

OFAC’s announcement described several techniques allegedly used by al-Samarra’i to disguise ties to the Iranian petroleum sector, including carrying out ship-to-ship transfers at night and spoofing location signals sent via vessels’ automated identification systems – all familiar features of Iran-related sanctions actions.

More unusual, however, was OFAC’s focus on the blending of Iranian and Iraqi oil. In some cases, this process was likely carried out at Iraqi terminals, and in others, at sea, the authority said.

Blending had featured once before, in a July 2025 sanctions action targeting Iraqi-British national Salim Ahmed Said, who OFAC said controlled UAE-based firm VS Tankers, as well as VS Oil Terminal, located in Khor al-Zubair in Iraq.

OFAC accused vessels affiliated with VS Tankers of assisting Iranian exporters in blending Iranian and Iraqi oil, obscuring its origin and moving it via ship-to-ship transfers. It also said VS Oil Terminal managed six storage tanks used for receiving and blending the oil.

Floating storage and offloading (FSO) vessels are widely used in oil trading, serving as a useful mechanism for holding oil temporarily while a buyer is found, facilitating back-to-back sales or simply waiting for a slump in demand to be reversed.

However, the cases of Babylon and VS – and a first-of-its-kind investigation into those companies’ interactions with FSO vessels – reveal a troubling history of potential sanctions evasion that was previously overlooked.

Investigation: Iranian oil and floating storage

Following the sanctions actions against Babylon and VS, GTR partnered with Deep Blue Intelligence (DBI), a joint programme between Blackstone Compliance Services and Pole Star Global, to investigate the potential commingling of Iranian-origin and legitimate crude stored on FSO vessels.

Focusing on a six-month period leading up to early October 2025, DBI identified all tankers above 10,000 tonnes with significant dwell times within the Persian Gulf.

It then reviewed each one to ascertain which were acting as floating storage, which were feeder vessels from nearby terminals, and which were in regular transit.

At least eight tankers were found acting as FSO vessels, all based at a single point mooring site outside of Basra’s anchorage.

This is a common practice for oil exports from the Iraqi port of Khor al-Zubair, where larger tankers cannot access the terminals, requiring the use of smaller feeder vessels for loading.

GTR can reveal that of those eight tankers, all but one conducted ship-to-ship transfers with at least one vessel linked to VS, Babylon or another US-sanctioned entity.

Over the 180-day period examined, tankers associated with VS made at least 48 ship-to-ship transfers to the FSO vessels, the investigation found.

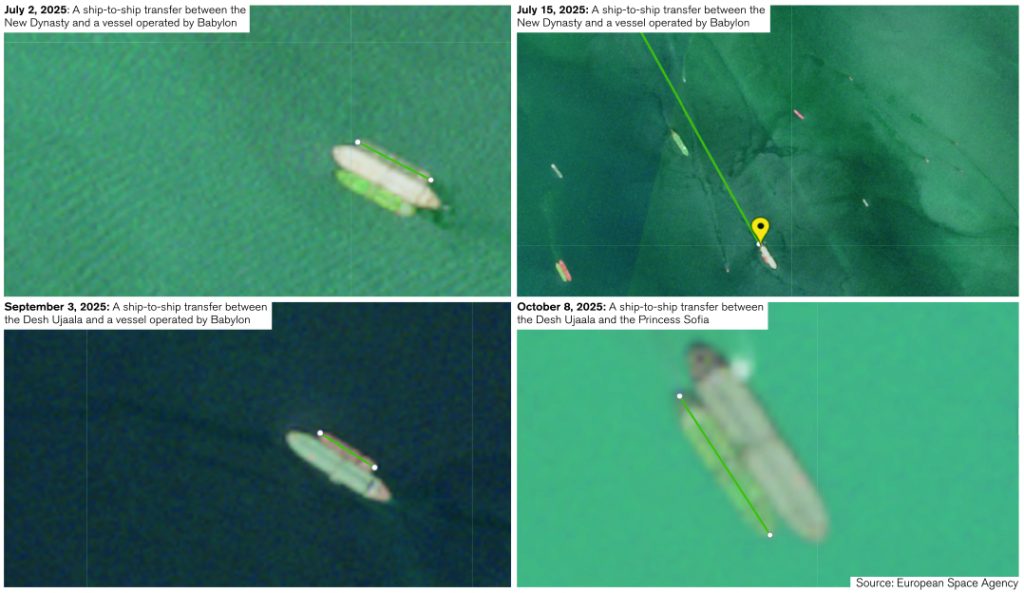

Six more transfers to FSO vessels from Babylon’s fleet were visually confirmed by DBI using satellite imagery.

“This paints a grim picture,” says Blackstone director David Tannenbaum, who led the investigation alongside Pole Star senior solutions engineer Richard Aguilar. “Every FSO vessel we identified, save one, conducted multiple ship-to-ship transfers with at least one of the vessels listed as high-risk.

“Up until VS’s and Babylon’s designations, the FSO vessels were receiving cargo originating from the VS Oil Terminal on a daily basis. This means that at any given time, all but one or two FSO vessels likely had Iranian-origin goods aboard.”

One such FSO vessel was the New Dynasty, a Greek-owned and managed crude oil tanker built in 2003.

“This paints a grim picture. Every FSO vessel we identified, save one, conducted multiple ship-to-ship transfers with at

David Tannenbaum, Blackstone Compliance Services

least one of the vessels listed as high-risk.”

The New Dynasty received cargo from high-risk vessels at least 41 times, including from a VS-owned feeder vessel, multiple Babylon vessels and the Princess Sofia, which was previously managed by US-sanctioned Sea Art Ship Management and has long been considered high-risk by DBI.

The Princess Sofia also made numerous port calls to the VS Oil Terminal in 2025.

Tannenbaum says there is “no indication” that the New Dynasty knew it was receiving cargo from problematic vessels; it was only once OFAC alleged VS had been blending Iranian and Iraqi oil that this risk was in the public domain.

New Shipping Ltd, which manages the New Dynasty, tells GTR the company complies with all applicable sanctions laws, is not aware of any instances where it supported shipments involving blended Iraqi-Iranian oil, and has not engaged in business with VS or Babylon since their designation.

It is likely almost all of the FSO vessels’ exposure was unwitting, Tannenbaum says.

For instance, the Desh Ujaala, a tanker owned by India’s state-owned oil company, received three transfers from Babylon-operated ships, as well as one from the Princess Sofia.

One vessel, however, stands out for its apparent ties to VS: the Australia. Operated by VS Shipping DMCC, which was not sanctioned by the US but shares the VS name, it took down its website the same day VS Tankers and VS Terminals were targeted.

The Australia was found to have carried out several ship-to-ship transfers with high-risk vessels, again including the Princess Sofia, as well as two managed by Babylon.

The game-changer

The Babylon and VS cases have far-reaching implications for the oil trading market, says Tannenbaum, a former compliance specialist at OFAC.

“Now we have confirmation [from OFAC] that Iranian and Iraqi oil is being blended onshore in Iraq,” he says.

“That changes the game, because it’s no longer just whether vessels are coming from Iran, doing ship-to-ship transfers, location spoofing and so on. Now the oil can legitimately be coming from Iraq – or that’s what the certificate of origin says – but it might be blended with Iranian oil that is subject to sanctions.”

That also places financiers, traders and insurers under scrutiny, because OFAC’s aggressive approach to sanctions – typified by the US government’s so-called maximum pressure campaign against Iran – means even inadvertent links to Iranian-origin oil can result in damaging enforcement action.

No matter how good maritime intelligence is, Tannenbaum says, if blending is happening onshore in a supposedly allied country, companies “now have to question everything that’s coming out of there”.

“It’s one of those ‘oh shit’ moments, where you wonder how much more of this activity is going on.”

“What I have heard from those operating in the sector is that certificates of origin are for sale for as low as US$15,000.”

Lauren Talerman, Akin

On the documentation side, some of the techniques used to avoid detection are similarly sophisticated.

“What I have heard from those operating in the sector is that certificates of origin are for sale for as low as US$15,000,” says Dubai-based lawyer Lauren Talerman, a partner at Akin specialising in export controls, sanctions and anti-corruption.

“It’s very difficult to authenticate these kinds of shipping documents, and ultimately you’re relying on the assurances being provided by your counterparty and your own due diligence.”

Talerman adds that illicit activity is not limited to areas around Iran.

“Iran knows the Middle East is being monitored, and so many vessels have been designated. Iran needs to diversify the ways that it gets its oil to market, and one way of doing that is making sure it has different places to store oil in the interim without that being concentrated in one geography,” she tells GTR.

“When we see certificates of origin from places in Southeast Asia, for example, that can be a red flag to us, particularly if it’s a country that is not really known for producing or refining oil.”

A US-based lawyer, speaking on condition of anonymity due to client sensitivities, says they have seen evidence of a “cottage industry” in Malaysia, where oil inspection services will issue seemingly legitimate paperwork that hides Iranian involvement in blended oil cargoes.

Who’s buying (and who’s paying)?

China is the largest buyer of Iranian oil, which is typically delivered to smaller ‘teapot’ refineries. Its influence over this market is reflected by the amount of Iranian oil stored at sea at any given time.

Emma Li, a China oil market analyst at Vortexa, says that during 2025, a slowdown in Chinese oil imports and ample onshore inventory in Shandong have left greater volumes of Iranian crude sitting aboard FSO vessels.

Data provided to GTR by Vortexa, an energy marketing intelligence company, shows that Iranian crude oil-on-water – including cargoes in floating storage, in transit and undergoing ship-to-ship transfers – has been building throughout much of the year.

As of October 12, volumes had reached an all-time high of 149 million barrels, Li says. Vortexa data suggests this is a year-on-year increase of more than 44%.

For banks, traders, shipping companies and insurers in many other markets, unwitting exposure to Iranian oil being stored at sea carries a material risk.

The uncompromising nature of OFAC’s Iran-related sanctions programme means there is little leeway for a company that inadvertently accepts cargo where oil has been commingled.

“Under the Russian sanctions regime, there is a carveout for the tank heel, which is what remains from a previous cargo that was in the storage,” Akin’s Talerman says.

“Under the Iranian sanctions regime, one drop of Iranian oil can impact the full tank. If you are buying oil that has been on a vessel previously involved in Iranian oil, you will want to be sure that tank has been scrubbed and there is no blending whatsoever.”

Even in situations where earlier cargoes were authorised by authorities, Talerman says entities would need to assess that authorisation to determine the status of residual molecules.

Because any blending of Iranian oil within a cargo aboard an FSO vessel “taints the entire shipment”, there could be far-reaching consequences for numerous parties involved in a trade, Blackstone’s Tannenbaum says.

“If you’re a large oil company and you’ve trusted an FSO to take good care of your cargo while you find a buyer, then all of a sudden they’ve commingled it with Iranian oil, you can’t separate that back out,” he says.

“That oil company is going to turn around and sue the crap out of the FSO, and anyone in that chain – whether it’s the vessel operator, the port operator arranging the ship-to-ship transfer, any brokers or commodity traders – is going to be on the chopping block for arbitration and lawsuits.

“It could be hundreds of millions of dollars at stake.”