Following the UK’s decision to withdraw from the EU, companies have finally been given a glimpse of the potential terms by which they will be able to trade with their clients overseas. Duncan Lodge, Senior Director, Trade & Supply Chain Finance Product at Lloyds Bank, looks at some of the implications for company value chains.

After much anticipation and uncertainty, British companies were finally given a glimpse of the UK government’s vision for Brexit through the positioning paper, published in late 2017. Whilst openly aspirational, the views speak of the importance of securing an interim close association with the existing European Union Customs Union, followed by the implementation of two novel approaches:

- A highly streamlined customs arrangement that makes substantial use of technology to reduce friction at borders;

- A new customs partnership with the EU that, in effect, continues to give the UK access to the Customs Union (along with the current tariffs applied to non-EU countries), with the ability to negotiate bilateral free trade agreements

Though developments offer encouragement for many British businesses, the ability for the UK government to secure such a deal is by no means certain; will the EU be willing to let Britain, ostensibly, have their cake and eat it? And whilst a potential boon for companies that trade in goods, this still leaves companies that trade in services, which make up the bulk of the UK economy, without much-needed clarity. The government’s ‘Future Partnership Paper’ makes some reference to services, acknowledging the substantial role they play in the UK economy, but ultimately acknowledges that an “independent trade policy” would be required to “fully capitalise on those opportunities”.

As noted in previous articles on the matter, the Customs Union enables tariff-free trade with all EU member states, whether for imports or exports. What the proposed model doesn’t guarantee, however, is ongoing harmonisation of customs rules and standards across the UK and Europe (for example, technical specifications and rules of origin). Whilst the government is intending to use digitisation to drive a reduction in friction at borders, there is no guarantee that this will completely mitigate the spectre of additional non-tariff barriers to trade, which will continue to be a concern for companies sitting either side of the UK border.

What is now at least relatively clear is that the outcome of the negotiations will likely be one of two scenarios (ignoring any interim transition period):

- The UK successfully maintains some form of Customs Union membership with the EU, enabling tariff-free trade on goods and relatively low friction at borders, or

- The UK and EU revert to trading on WTO Trade Rules.

Based on the most recent negotiations and government positioning as this publication goes to press, it would seem that the UK staying in the Single Market is now highly unlikely without some form of cross-party intervention in the Houses of Parliament. For the purposes of this article, therefore, I shall focus on the two scenarios outlined above.

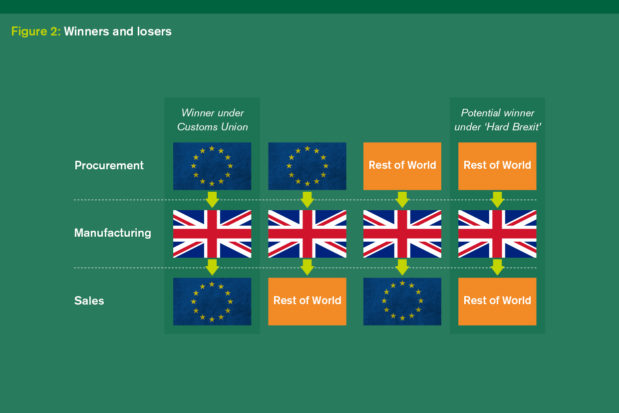

In either of these scenarios, crucially, there will be winners and losers, and winning or losing will be based on the value chains that a company maintains today, and their ability to adapt, de-risk and build new value chains in the future.

Winners and losers

In the wake of increasing globalisation, many companies, including small to medium-sized enterprises, have built extended value chains; sourcing inputs from multiple countries to then sell to multiple countries. Embracing globalisation has enabled companies to optimise their business and create much greater value, finding the very best suppliers the world has to offer, the cheapest or most efficient operating environments, the very best markets for their goods or services and a globally mobile workforce. For many UK firms today, value chains have been built to take full advantage of the existing tariff-free and frictionless borders between EU countries, not to mention the large highly-skilled labour market. Let’s take a look at a real example of a Lloyds client (see figure 1).

It is important, however, to consider that not all companies are reliant on the EU for their value chains. Raw materials are less frequently sourced from EU countries, often coming instead from emerging markets. If, for example, a company’s client base comprises buyers in the US or Asia (where no EU Free Trade Agreement exists, and the UK operates under WTO Most Favoured Nation, MFN, tariffs today), they will have little or no reliance on access to the EU Single Market, or any future Customs Union relationship, and may have a reduced currency exposure. Such a company will be experienced with trading under WTO MFN tariffs, facing them both as they source inputs, and as they sell to their clients. For such companies to win substantially under Brexit, two things must happen: 1) the UK must make a decision to either unilaterally or selectively lower its own WTO MFN tariffs (helping reduce costs on the inward value chain), and 2) negotiate bilateral free trade agreements with markets within which the company operates (see figure 2).

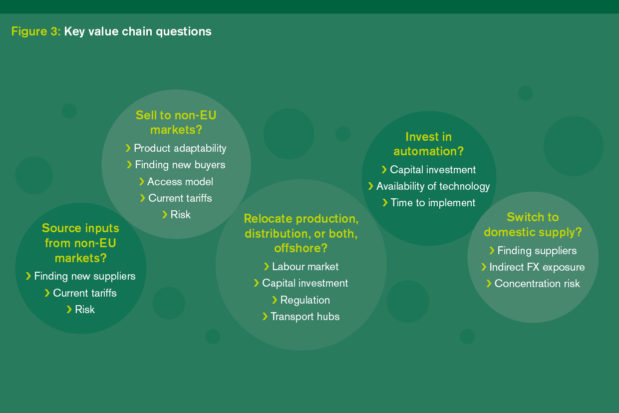

In reality, as a company gets larger, their value chains can become increasingly complex – often touching numerous countries around the globe. This presents UK-based companies with a true conundrum – can their value chains be amended or adapted in such a way that they can de-risk or take advantage of the potential outcome of the negotiations? (see figure 3)

Bridges versus barriers

As referenced before, the ability to move goods and services across borders smoothly and efficiently is highly important to both UK and EU companies. Importantly, it is often the non-tariff barriers, such as technical specifications and rules of origin, that bite the hardest, increasing cost and tying up valuable working capital. Such barriers can be hard to identify through anything other than bitter experience from trying to trade with a given market, or from conversations with companies

that are experiencing those barriers today.

From the bank’s survey in Q2 2017 carried out in conjunction with YouGov1, 21% of companies that export specified the administrative costs of customs as the biggest barrier for their ability to trade, with tariffs coming in second place. Given that 85% of respondents trade with the EU, it’s possible that even the supposedly streamlined Single EU Market is not perhaps as easy to navigate as one would be led to believe1. It’s certainly true that for non-EU companies trying to sell goods to the EU the process can be challenging.

For example, for citrus fruits, not only are there duties and tariffs, there are a complex array of marketing standards that must be met. These marketing standards include requirements such as fruit being free from abnormal surface moisture and blemishes, and having the requisite sugar to acid ratio and colour2. Not only is it therefore challenging to achieve such requirements as a farmer, but the fruit will need fairly detailed and potentially subjective checks at the EU border. If the UK fails to secure the model set out in the positioning paper, it will not just be British farmers that will quickly need to become familiar with such requirements.

GATS all, folks

For service companies the challenges are slightly different, especially given the lack of clarity over services in the government positioning paper. Service companies, with the exception of Financial Services, will need to start operating under WTO ‘General Agreement on Trade in Services’ (GATS).

In a nutshell, GATS is a broad framework that covers the provision of services under four models of supply:

1. Cross-border supply (where provision of services happen remotely, such as a lawyer giving legal advice over the phone)

2. Consumption abroad (where a tourist or patient travels to another country to receive a service)

3. Commercial presence

4. Presence of natural persons (where someone travels to another country to perform a service, for example doctor or a teacher).

The main issue with GATS is that, unlike WTO MFN tariffs, it enables a wide degree of latitude for a country to define how it is implemented across its different service industries. Each member is able to apply exceptions, which are often referred to as “limitations” or “reservations”. Importantly, even the absence of such exceptions in a country’s GATS schedule does not necessarily mean that certain industries are or will be de-regulated. The EU’s list of exceptions is fairly substantial (totalling some 94 pages in length) and can be found online3. Each service has its own unique restrictions across each model of supply. As an example: “In all EC Member States services considered as public utilities at a national or local level may be subject to public monopolies or to exclusive rights granted to private operators.”4 This is, in essence, a ‘get out of jail free’ card for the EU, since it includes a whole plethora of potential services within the definition of public utilities, including scientific and technical consulting services. Careful reading of the EU GATS Schedule is required for any UK service company that is modelling a worst-case scenario, where no specific agreement can be made on services, but regrettably there could be an argument for many firms that it would be simplest to open a new EU-registered operating entity to access the member states, bypassing the complex country and sector-specific requirements. Clearly this has implications not only for a company’s investment strategy, but more broadly for the UK labour market and the British government’s tax receipts, and overall GDP.

It will also be important for UK service companies that the government promptly enter WTO Trade in Services Agreement (TiSA) negotiations. TiSA represents an attempted move by a number of WTO members (some 23 in total, including Europe) to move towards freer trade in services. Unfortunately, given that negotiations have been ongoing since 2013 with 21 rounds of negotiation to-date, followed by a general agreement to put the negotiations on hold, there is relatively little further comfort for companies facing a cliff-edge scenario.

If you fail to prepare, prepare to fail…

Ultimately, even with the government’s positioning paper there is still substantial uncertainty for companies due to the complexity of the negotiations between now and any final agreement. However, whilst speculative, we at Lloyds firmly believe that companies that proactively manage their value chain risk will be more likely to survive and adapt to whatever the future relationship with the EU looks like.

Companies can significantly reduce their value chain risk by focusing on four key pillars:

- Unlock working capital

companies that have strong working capital positions will be better able to weather whatever challenges the future might bring. There are many ways to unlock working capital, including via payment terms renegotiation, stronger credit control, and bank financing. A focused investigation into bottlenecks and solutions can often yield material improvements. Lloyds Bank’s recent update to the Working Capital Index shows that across UK firms there is at least £535bn of cash that is currently tied up in excess working capital.

- Focus on productivity

Britain lags behind other developed economies such as the US, Korea, Canada and Germany in terms of productivity. If tariffs do start to erode profits, increased productivity will ultimately lead to a lower cost base, helping companies manage the tariff impact and continue to provide competitive pricing. With access to labour a real concern, especially in the service and construction industries, companies should consider how they can drive productivity via automation/new production technologies.

- Trade with the world, not just the EU

regardless of how the EU negotiations play out, companies should be looking to take advantage of sterling’s depreciation by identifying new markets for their products and services. This will help minimise the impact of any future loss of access to Free Trade Agreements or possible slowdown of growth. New markets deliver new ways of doing business and so, as previously noted, companies should ensure that risk management and working capital is front of mind. Companies also quickly need to consider the implications of any extra tariffs and customs requirements on their inward supply chain – is it time to switch some key suppliers?

- Be risk aware

a financial loss can have a huge impact on cash flow. Greater macroeconomic uncertainty could lead to greater client payment delays or failures, and new markets means new risks and ways of doing business. It is therefore important that firms have a resilient risk management strategy in place, especially when starting to look at markets outside of the EU. Companies should be considering the full range of risk mitigation techniques, from letters of credit and guarantees, through to credit insurance and UK Export Finance offerings.