The Middle East and North Africa (Mena) region’s economic performance in 2017 was muted, writes Rebecca Harding. GDP growth across the region is estimated by the World Bank to have been just 1.7%, down from 5% in 2016. Two factors were behind the weaker economic performance: firstly, oil prices continued to be below the US$70 a barrel “breakeven” level calculated by the IMF. Adjusting to the lower oil price has placed pressure on the biggest regional economies, particularly Saudi Arabia1. The adjustment has improved conditions for oil importers, but had the opposite effect on oil exporters.

Secondly, the region’s geopolitical risk profile has changed substantially. The whole region has been affected by the continuing conflict in Syria, the Qatar blockade and heightened tensions between the US and Iran, and between Saudi Arabia and Lebanon. The main consequence of this has been a heightened perception of risk in the region which, in turn, has the potential to affect investment flows.

Nevertheless, the World Bank’s January 2018 report suggested that, if these risks could be moderated, then economic growth could pick up considerably to around 3%2, which will depend on oil prices remaining relatively high compared to previous years.

This year’s Trade Briefing looks at the key patterns in regional trade, growth sectors, the role of external trade partners such as China, Turkey and Russia and the trade implications of geopolitical tensions within the region.

Against the backdrop of geopolitical uncertainty, we show how Mena’s exports are declining in value terms. This is a function of the need for the region’s oil producers to bring down the cost of production in order to cater for a price which now seems settled at below US$70 a barrel. Imports, however, are growing and alongside this, growth in services suggests that real diversification is taking place through consumer demand, rather than exports.

Mena trade and growth

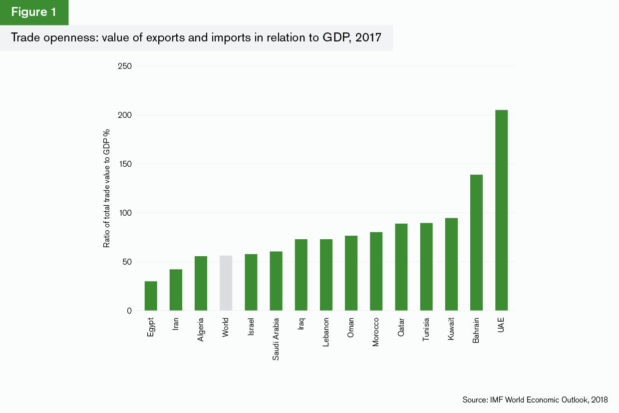

The Mena region is highly open to international trade because of its geographical location and need to import much of what it consumes (Figure 1). Trade has a significant bearing on GDP, in some countries more than others. Figure 1 shows the relationship between total trade (exports plus imports) and the value of GDP in each country in the region for which data is available.

As a trade hub, the UAE has the highest trade openness, with trade accounting for more than 200% of its GDP. The dominance of the port hub in Dubai means that there is a substantially higher value in goods going through Dubai than being consumed by the country itself.

Trade openness tends to be less marked in countries either where there is a strong self-sufficiency or where trade is under-developed, such as in Egypt, Iran and Algeria.

For all other countries in the region, trade openness is higher than the global average of 56%.

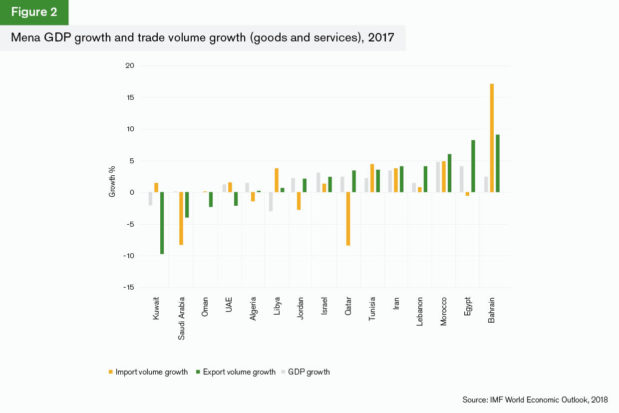

Across various countries, the extent to which trade drives GDP is very different (Figure 2). Before the global financial crisis, there was an assumption – based on World Trade Organisation analysis – that trade volumes would grow at around twice the rate of GDP growth. This relationship broke down in the aftermath of the crisis and in 2016 trade growth was on average just 0.8% of GDP growth.

For most countries in the Mena region, import or export volume growth is higher than GDP growth. The notable exceptions are the nations where oil trade dominates, including Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Oman, the UAE and Algeria. Libya and the UAE’s import volume growth is higher than that of GDP although they are major oil exporters, reflecting on the one hand Libya’s heavy import dependency and, on the other, the UAE’s role as a trade hub. Similarly, Kuwait, Tunisia and Bahrain have higher import growth than GDP growth. In the case of Tunisia and Kuwait, this is in higher-end consumer products whereas for Bahrain the imports are in infrastructure-related sectors.

Of greater interest, perhaps, are the countries where both GDP and trade growth are strong and positive, such as Bahrain, Morocco, Iran, Tunisia and, arguably, Lebanon.

Bahrain’s strong trade outlook, albeit from a relatively low base, is predominantly a reflection of its growing position in oil and gas as its new pipelines come on stream.

Morocco, in contrast, is an oil importer and its economy has not fared as badly as a result of the fall in oil prices. Last year’s GTR+ Mena report noted that Morocco is less dependent on commodity prices and has the potential to be more of a manufacturing hub. The strong GDP growth alongside strong trade growth seen in Figure 2 demonstrates that it still has that potential.

Mena trade and the data challenge

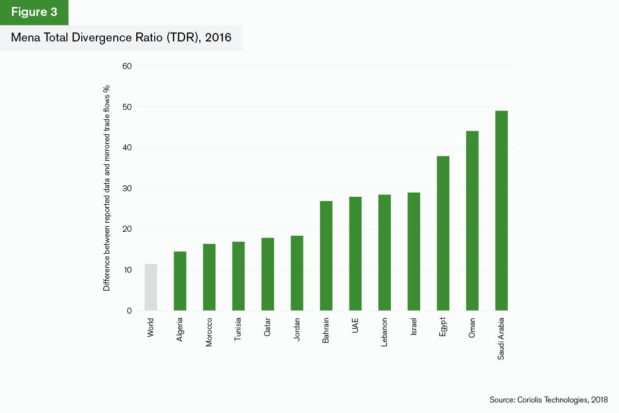

Reporting on trade in the Middle East and North Africa has historically been difficult. The countries in the region have reported their data unreliably, and these weaknesses were a key theme of last year’s GTR+ Mena report. This remains the case this year, as illustrated in Figure 3, which shows the average divergence between what a country says it is trading in its nationally available data, and what Coriolis Technologies finds it is trading when its trade flows with partner countries are taken into account. This involves a process of averaging trade flows, weighting the data in favour of the better reporting country.

The divergence between reported and actual trade flows in Figure 3 is a ratio weighted for the balance of imports and exports in total trade for each country, showing the divergence between publicly available data and the data that is derived through the analysis of trade flows with partners.

While every country in the region has a worse Total Divergence Ratio (TDR) than the word average, Saudi Arabia is particularly bad with an average 49% difference in the total trade it reports versus the total trade that we see by mirroring the data.

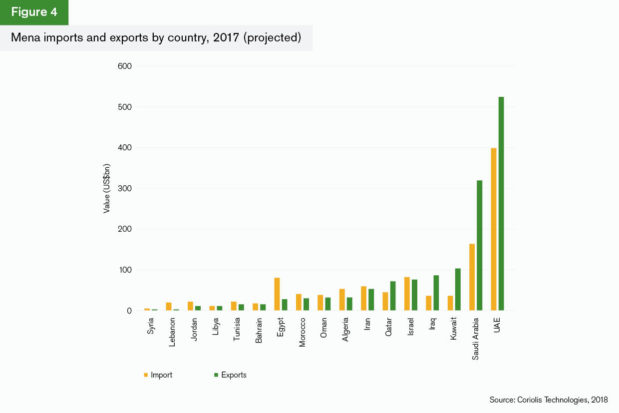

Improvements in data collection processing, both at the United Nations and at a country reporting level, have reduced the number of missing data points in country statistics within the Mena region and this has revised the values of trade in publicly available data. Coriolis Technologies uses a new approach to calculate the average value of trade flows between countries. The two approaches combined now means that the data in this report is vastly improved on trade data that has been previously available. It also means that the trade balance across the region has shifted, and we now know that it is the UAE – and not Saudi – which is the largest exporter in the region (Figure 4)3.

This is a remarkable turnaround and reflects:

- The drop in oil prices since 2014, which has significantly reduced the value of trade in oil exporting countries in the region.

- The increased diversification of the UAE’s trade portfolio as its port and trade hub role grows. Although oil remains the country’s largest sector of trade, it is nevertheless more diverse in terms of what it imports and exports compared to Saudi Arabia.

- An improvement in data collection and reporting over the last year, which indicates the extent to which the region is driving towards compliance with global standards in this respect.

Mena trade is still predominantly oil

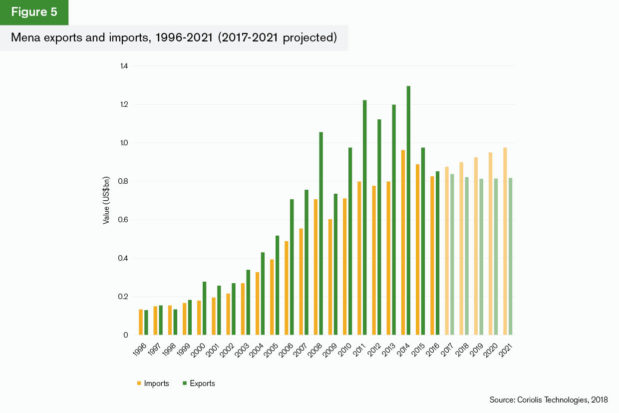

Trade in the Mena region remains dominated by oil and gas. Oil prices did not rise to breakeven levels last year and, as a result, trade value growth was relatively flat (Figure 5). The largest trading nations are the oil exporters (UAE, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait) and these economies have exhibited slower growth as a result. 2017 saw a net trade deficit in the region for the first time in 20 years. The 2017-2021 data is a projection but reflects the higher average oil prices during the course of 2017 restoring the value of the trade surplus. The projections show an improved outlook for the region’s exports.

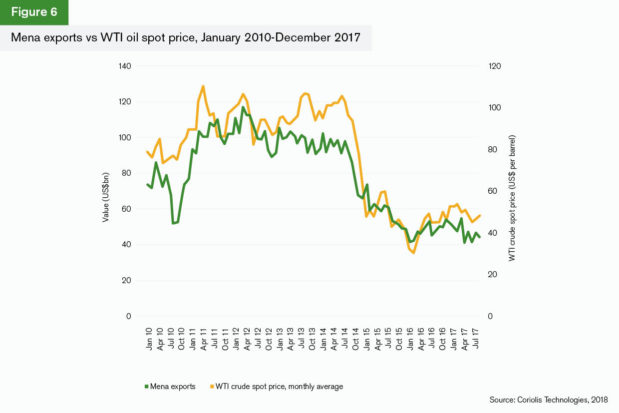

There is little in the near term to indicate that goods exports will diversify away from their current dependency on oil. The correlation between the region’s trade and the price of oil is very high at 92% (Figure 6), compared to the equivalent correlation for global trade, which is 78%. This suggests that any drop in oil prices is fed almost immediately into the value of Mena trade.

It is clear that this over-dependency on oil has affected the region’s economic health. As noted previously, the region’s GDP showed low or negative growth in many of the oil exporting countries.

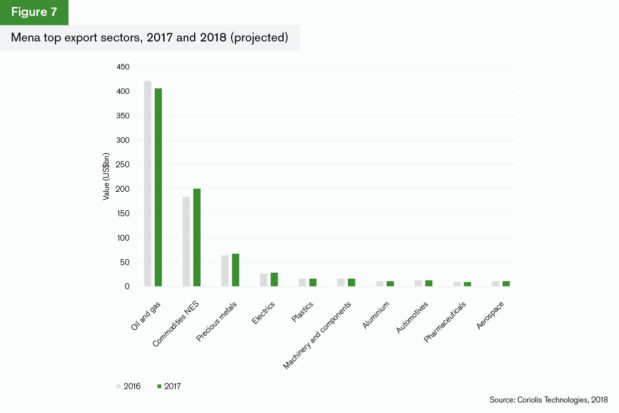

Oil and gas dwarf other sectors in the region (Figure 7). While the gap between exports of oil and gas in 2017 and 2018 is narrower than it was in 2015 and 2016 as reported last year, oil and gas exports are still twice the level of the next largest sector, commodities not elsewhere specified (NES). Since commodities NES are known to be closely correlated with both trade in oil and gas and trade in military goods, the fact that the value is nearly US$200bn in 2017 does not suggest any major diversification. The third largest export sector is precious metals, which includes gold. This is also a sector highly dependent on its spot price on international markets.

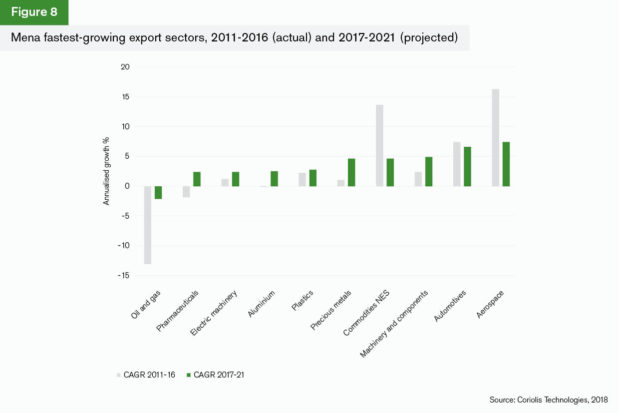

The fastest-growing export sectors, however, do suggest that there is some momentum towards greater diversification (Figure 8). Nevertheless, the fact that aerospace exports have grown at a rate of 16.3% between 2011 and 2016 and are projected to maintain an annualised growth rate of over 7% to 2021 reflects the region’s role as a trade hub rather than as a manufacturer. Essentially, it is importing aerospace goods in order to re-export them and as such acting as a distributor rather than a producer. The same is true of automotives and machinery and components.

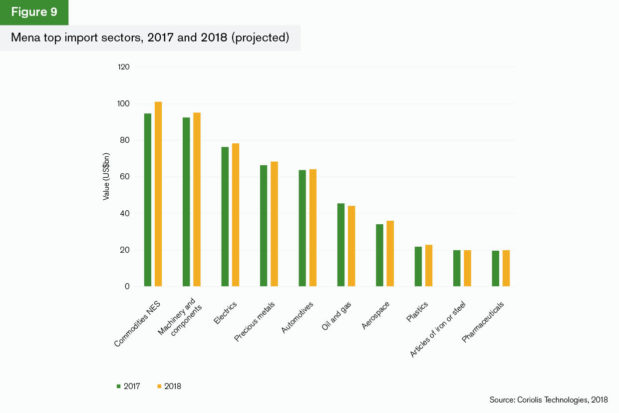

It may be that imports are evidence of diversification in demand patterns (Figure 9). Commodities NES are the biggest imported sector into the region and precious metals the fourth, but machinery and components, electrics and automotives were strong import sectors in 2017 and are set to grow into 2018. The increase in precious metals trade reflects the stronger prices of gold and silver, whilst higher levels of automotives and electrics indicate the growing importance of Mena as a distribution point between Europe and Asia. Aerospace is the sixth largest import sector and is also set to grow. This sector, along with electrics, contains a substantial amount of IT systems, data storage and satellites, indicating that the region is increasing its cyber-security and IT infrastructures.

This is corroborated by the rates of growth in imports (Figure 10). The fastest-growing import sector is aerospace, but pharmaceuticals is second and, combined with the significant growth in medical infrastructure imports in specific countries like the UAE (see further on in this report), this suggests that demand for medicine and medical equipment is increasing within the region. A greater demand for plastics and electrics may also be related to growth in infrastructure as these products are used in construction and IT infrastructure development.

A focus on Egypt

Egypt’s trade projections are for faster growth in the period 2017-2021 compared to 2011-2016. This suggests that the country may be re-entering the trade mainstream after the challenges of the Arab Spring and in light of the sustained security challenges it faces. Its imports are projected to grow annually by around 3% to 2021, having remained static since 2011. This is a sign that its infrastructure is building, and the fact that electrical machinery and automotives are among its fastest-growing sectors corroborates this: each is set to grow at above 3.2% annually to 2021.

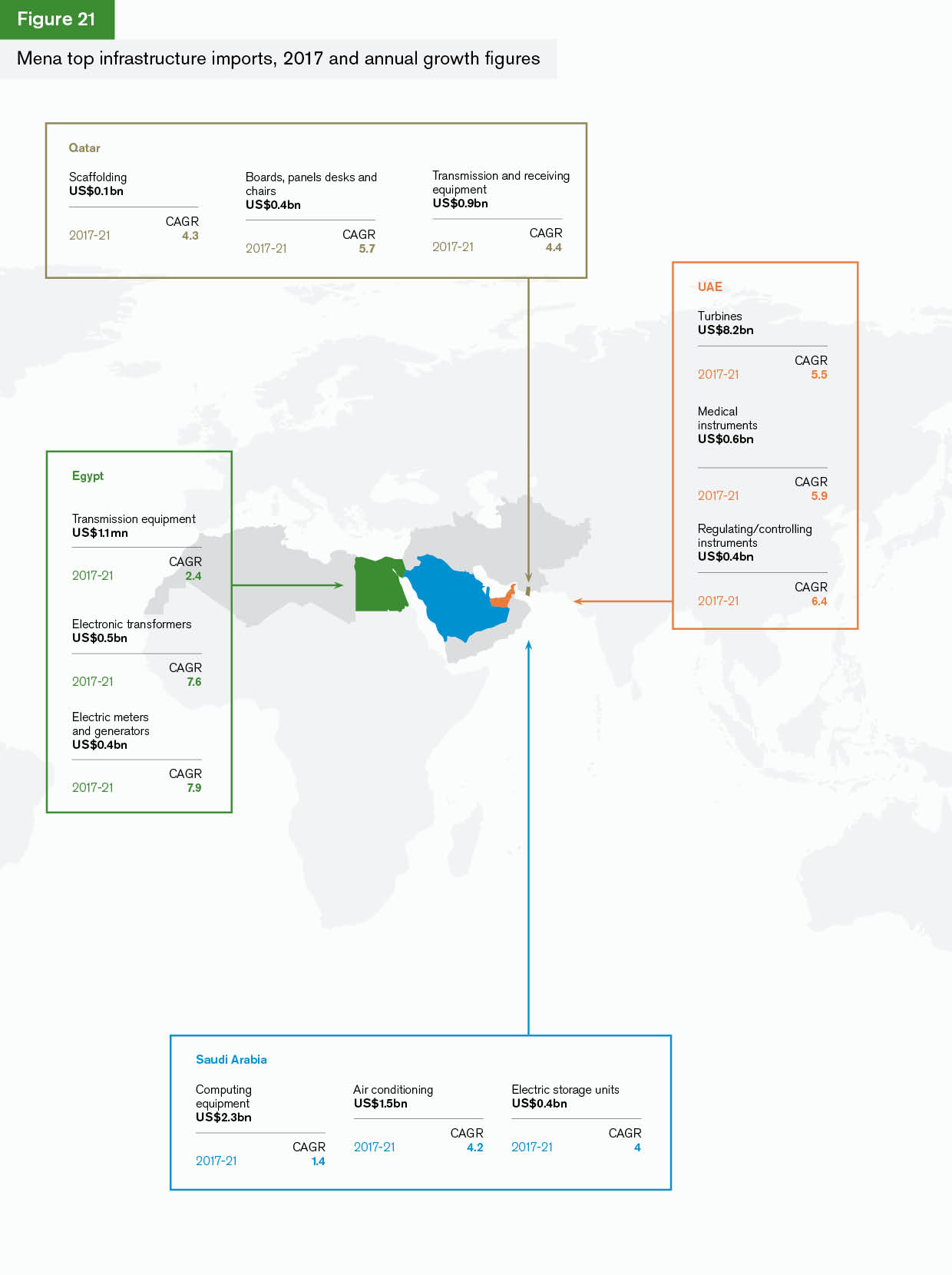

On a more detailed level, Egypt’s imports reflect the requirements of its security system. For example, its imports of reception equipment for signals are projected to grow annually by 10% to 2021 – communications equipment (part of electrical machinery) is the fastest growing area and also the largest. This is shown in further detail in the infrastructure chart later on in the Trade Briefing (Figure 21).

Additional research suggests that Egypt’s partner trade also reflects the geopolitical role it is now playing in the Middle East. Until 2016 the US was a larger import and export partner than Russia. By 2021, Russia is set to overtake the US and become Egypt’s third-largest trade partner after China and Germany.

A focus on the UAE

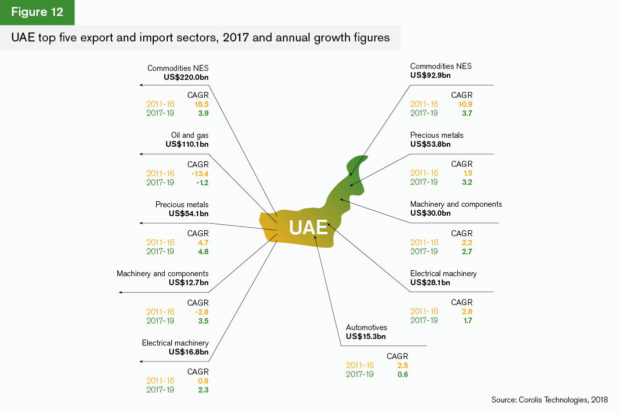

The UAE’s growth in trade is projected to be the fastest of any country in the region at nearly 10% in 2017-2018. The UAE’s role as a hub means that its trade is generally diversified: while oil and gas dominate its exports, it also exports machinery and components and electrical machinery, all of which are amongst its top five trade sectors. The UAE’s growth in each of these sectors – apart from oil and gas – is projected to be over 3% annually to 2021, suggesting that its role as a trade hub is increasingly important. The UAE imports infrastructure equipment to support its construction industry and big infrastructure projects such as Expo 2020. Equipment that supports large-scale engineering projects, such as engines is projected to grow quickly. On a more detailed level, the UAE’s imports reflect its growing reliance on a sophisticated medical infrastructure to support its cosmopolitan population: additional data research suggests that imports of medical devices are projected to grow by 6% annually to 2021. Separately, imports of equipment to regulate water levels and support the irrigation and port systems in the country are projected to grow at an annualised rate of over 5%.

Is Mena becoming more diverse in terms of its trading partners?

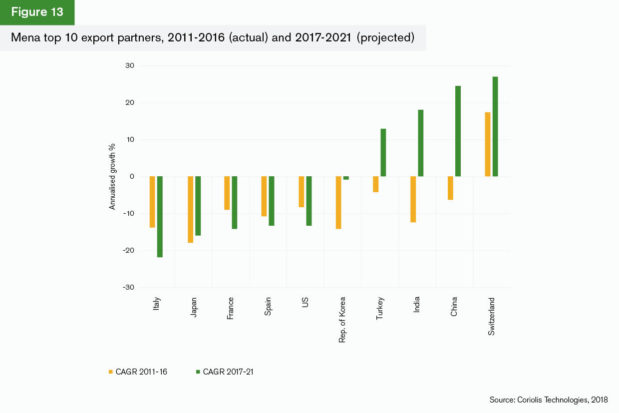

There is a noticeable shift in the importance of developed countries as trading partners for the region, with China being the most important. Mena exports over US$60bn to China and imports twice that (around US$126bn in 2017). The US is the second-largest import partner at approximately US$70bn in 2017 but the third-largest export partner at US$45bn. The shift in trade patterns is evident in the way in which trade with each of Mena’s top 10 partners has changed since 2011 (Figure 13).

Switzerland is the 10th-largest trading partner and imports mostly precious metals – an important sector for the Mena region – and its growth reflects both a rise in commodity prices and the smaller size of the trade corridor.

Of greater interest is the fact that growth in exports to China was negative between 2011 and 2016 but is projected to be positive in 2017- 2021. The same is true of both India and Turkey. Export growth to the developed nations of Europe, the US and Japan is set to remain negative for the years to 2021.

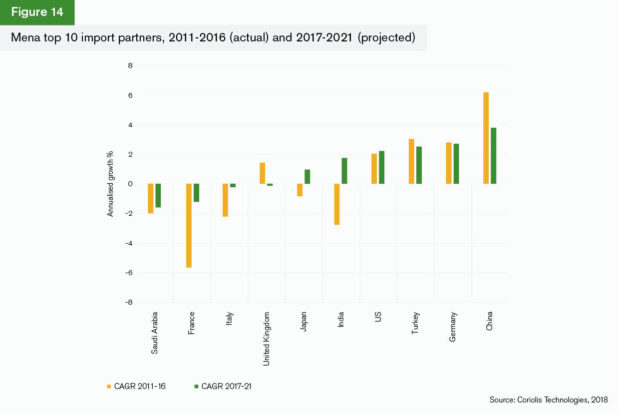

Figure 14 shows the annualised growth in imports from Mena’s top 10 trading partners. Again, China dominates, but Germany and the US are both projected to grow strongly over the next few years. Interestingly, India is expected to grow in importance as an import partner, and imports from Turkey, although slowing slightly, are still set to demonstrate robust growth (Figure 14).

The geopolitics of Mena trade

Turkey

Turkey is a satellite of the region and represents an interesting case in its own right. In 2017, Mena imports from Turkey were worth US$34bn, while exports to Turkey tallied US$17bn. Imports are predominantly in infrastructure products as Turkey has built strong expertise in specialist iron and steel that supports the oil and gas sectors in the Mena region. However, the rapid growth in commodities NES exports to Turkey up to 2016, and its ongoing growth annually of nearly 4% to 2021, reflect the strategic role that Turkey plays for the region both as a means of channelling Iran’s trade and as a strategic partner in counter-terrorism. Arms and ammunition (part of commodities NES) were a top export sector for Mena to Turkey in 2014 and 2015, and although these exports have now dropped, the amount of unclassified exports is still substantial and reinforces the importance of Turkey, not just in supporting infrastructure, but also in terms of its role for distributing sanctioned trade.

Russia

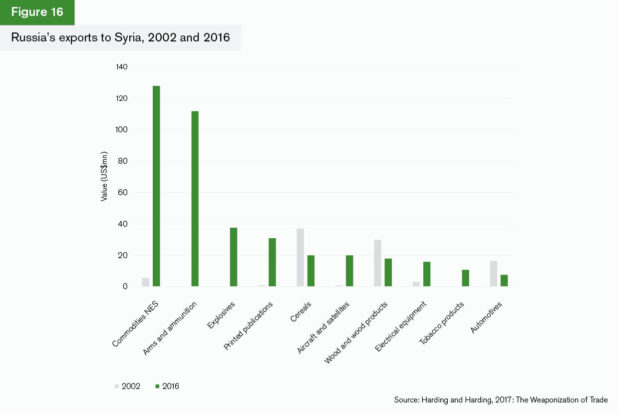

Russia’s role in the region is complicated by its geopolitical influence. It aligns geopolitically against Saudi Arabian interests and is increasingly close to Egypt. Figure 16 shows how Russia’s trade with Syria has changed since 2002. In 2002, Russia was predominantly supplying civilian goods, reflected in the top 10 sectors. While there may well have been trade in arms and explosives in 2002, they were not in the top 10. By 2016, Russia was directly supplying goods in support of its strategic ambitions in the region: arms, explosives, books and papers (which include manuals for assembling equipment).

Despite any political sensitivities, it is clear that Russia is becoming increasingly important for the region’s two main trading nations (Figure 17). The UAE is set to import more from Russia and although the rate of export growth is set to slow in the years to 2021, it is still likely to be positive. Saudi Arabia, perhaps driven by the pragmatism that its current economic position requires, is set to increase its exports at a rate of nearly 4% annually to 2021.

The Qatar blockade

Since June 2017, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, the UAE and Egypt have closed all ties with Qatar on the back of accusations that the country is supporting terrorism – an allegation which Qatar has denied. Transport links have been cut and, as a result, Qatar has had to look to other trade partners.

However, as this publication goes to press, despite original fears that the blockade may impact growth in the region, it does not appear to have had that much of an effect on trade itself. In fact, Qatari exports appear to have grown slightly in comparison to the other four countries (Figure 18). Additional analysis suggests that rates of export growth over the next five years will be particularly high to China (annualised to 2021 at 3.5%), Indonesia (3.9%), Germany (4.2%) and Egypt (4.7%).

For Bahrain, Egypt, Saudi Arabia and the UAE, the chart shows a marginal increase in trade since the blockade. The month of June 2017 itself saw a sharper drop in exports for every country except Qatar, where the drop was smaller. Subsequently, export trade in all countries except Bahrain appears to have grown slightly. This is likely to be the effect of slightly higher oil prices and a pick up in the global economy towards the end of 2017 rather than any direct influence of the blockade, positive or negative.

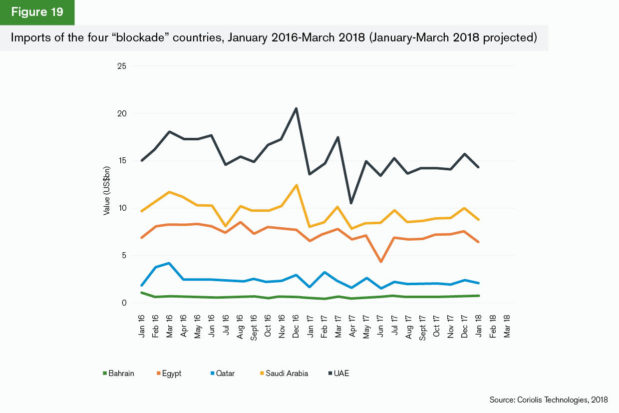

The same applies to imports: the blockade has made little or no difference to the overall levels since the blockade started (Figure 19). Imports appear to have grown somewhat in Saudi Arabia since June 2017. While they fell back in the month of June 2017 in the other countries, they have recovered and since the start of the blockade have shown a slight improvement.

There is little indication from elsewhere that the blockade has affected GDP growth. As indicated in Figure 2 earlier on, GDP growth for Qatar itself has been good, and while the country has nominally looked to Russia as an export partner, this does not show dramatically in its data as yet. In short, it is really too soon to tell whether or not there will be any lasting trade or economic effects.

New horizons – a focus on Africa

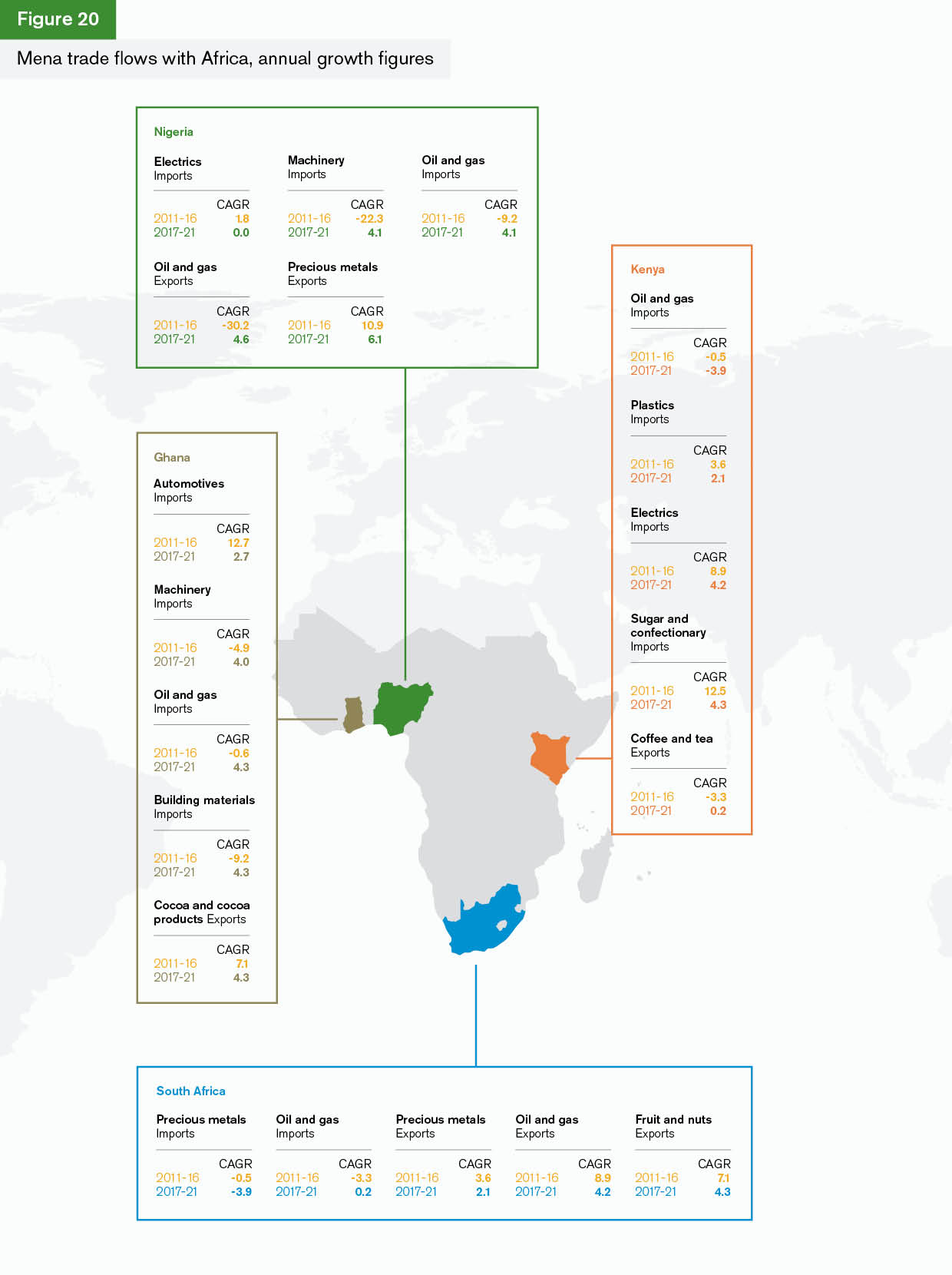

The trade relationship between the Middle East and Africa is highly commodity-based and, apart from South Africa, one which the Mena region dominates with exports of oil and gas and machinery and components to support the production of oil and gas in Sub-Saharan Africa. There is evidence that soft commodity imports from Africa are likely to grow, but the trading relationship has been deeply affected by the drop in oil prices. This has weakened both the African and Mena economies and, as a result, infrastructure exports to Africa have fallen back.

Ghana: Ghana has a substantial trade deficit with Mena. The Mena region exports automotives to Ghana, but otherwise supplies goods that help support the development of Ghana’s infrastructure. All of these sectors are set to grow over the next five years. The slow growth over the past five years reflects Ghana’s economic challenges as a result of the drop in oil prices. Ghana’s exports of cocoa and cocoa products to the Mena region have grown and will continue to grow.

Kenya: Although Kenya has a trade deficit with the Mena region, its largest trade flow is its exports of coffee and tea to the region. This reflects consumer tastes in Mena and its importance as a trading hub, given much of these products will be re-exported. Mena supplies oil and gas, which, because of the drop in oil prices, is set to decrease, as well as plastic goods and electrics (manufactured elsewhere in the world).

South Africa: The drop in oil prices has shifted the net trade balance between Mena and South Africa from a substantial surplus to deficit. South Africa is a major partner for oil and gas and for precious metals and stones (gold and diamonds): these are the two dominant sectors. Mena’s exports of oil and gas and precious metals are set to grow slowly or fall back, while imports from South Africa are set to increase on an annual basis.

Nigeria: Mena has a trade surplus with Nigeria and exports goods that will support Nigeria’s oil and gas infrastructure. The trade relationship between Mena and Nigeria has been visibly affected by the drop in the value of oil and gas imports from Nigeria, which is a consequence of the fall in commodity prices. This has reduced the value of the trade corridor but also weakened Nigeria’s economy, meaning that Mena is exporting less machinery and components and less electrics as well.

Infrastructure

Outside of commodities, the Mena region’s imports reflect its growing infrastructure requirements (Figure 21). In the years to 2021 the fastest-growing sectors are likely to be aerospace, pharmaceuticals, plastics and electrical equipment.

Much of this is defence and security infrastructure, hence the increase in aerospace and in both machinery and components and electrical equipment. The machinery and components category includes computers and data processing and storage systems, while electrical equipment includes digital devices and semi-conductors. Egypt, for example, imports dual-use goods to support its security infrastructure, while Saudi Arabia and the UAE import significant data storage and satellite systems, suggesting that they are also improving their IT and cyber-security infrastructures. The UAE’s major imports are in medical equipment and turbo jets – suggesting that it is improving its medical infrastructure as well as its irrigation and air-conditioning systems.

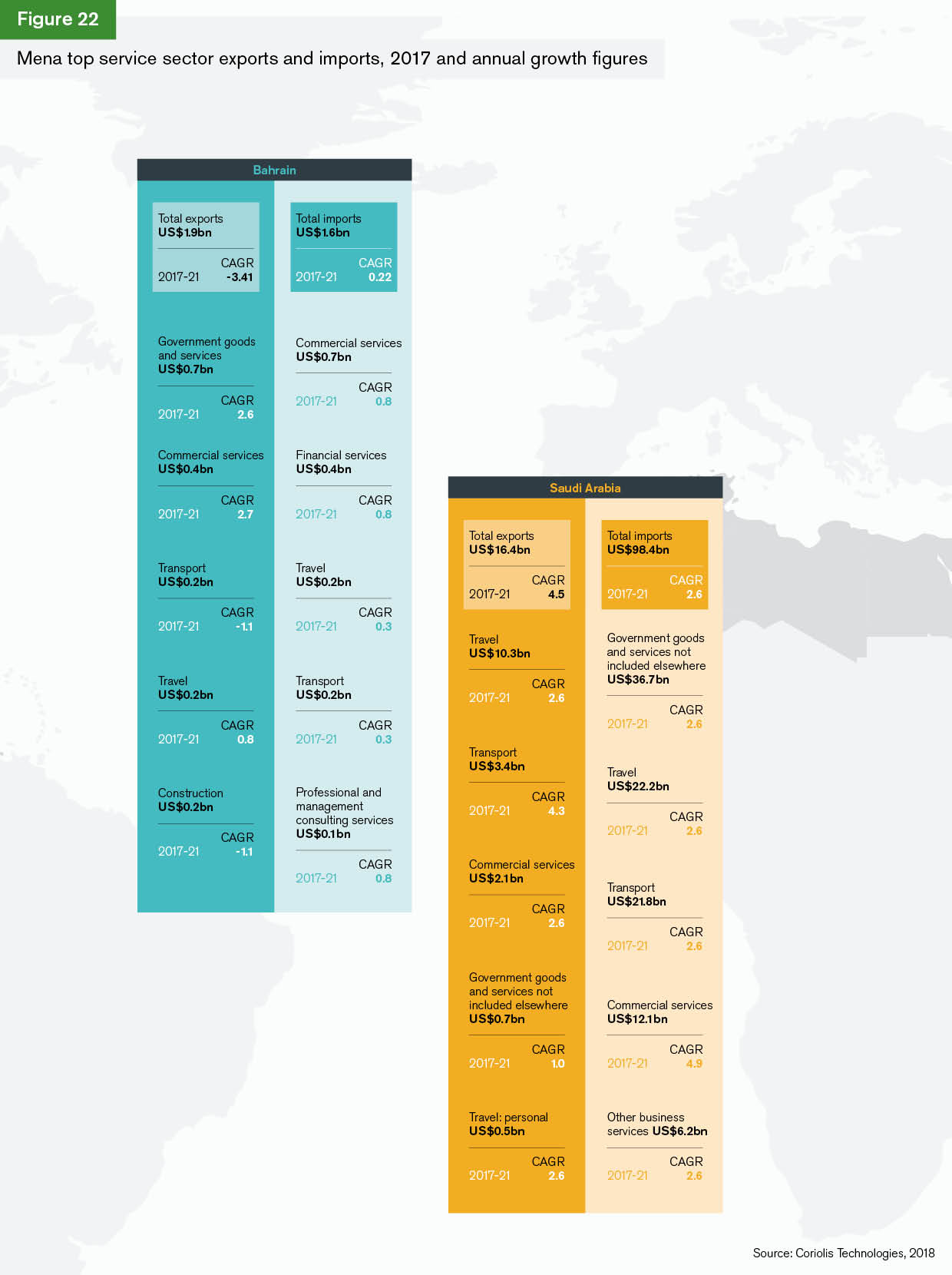

Services trade

Bahrain has a surplus in service exports. Its biggest export sector is government goods and services, which may include overseas missions, embassies and envoys, as well as government-owned entities, education and health. It works with a range of countries, including Saudi Arabia. Meanwhile, it has a service sector deficit in commercial services and financial services. On the other hand, Bahrain’s imports are set to increase slightly, although travel and transport will decline over the next few years. Construction exports are set to fall back but commercial services exports will grow by nearly 3%, reflecting the Kingdom’s emphasis on moving away from dependency on oil, even though oil represents 86% of its budget revenues.

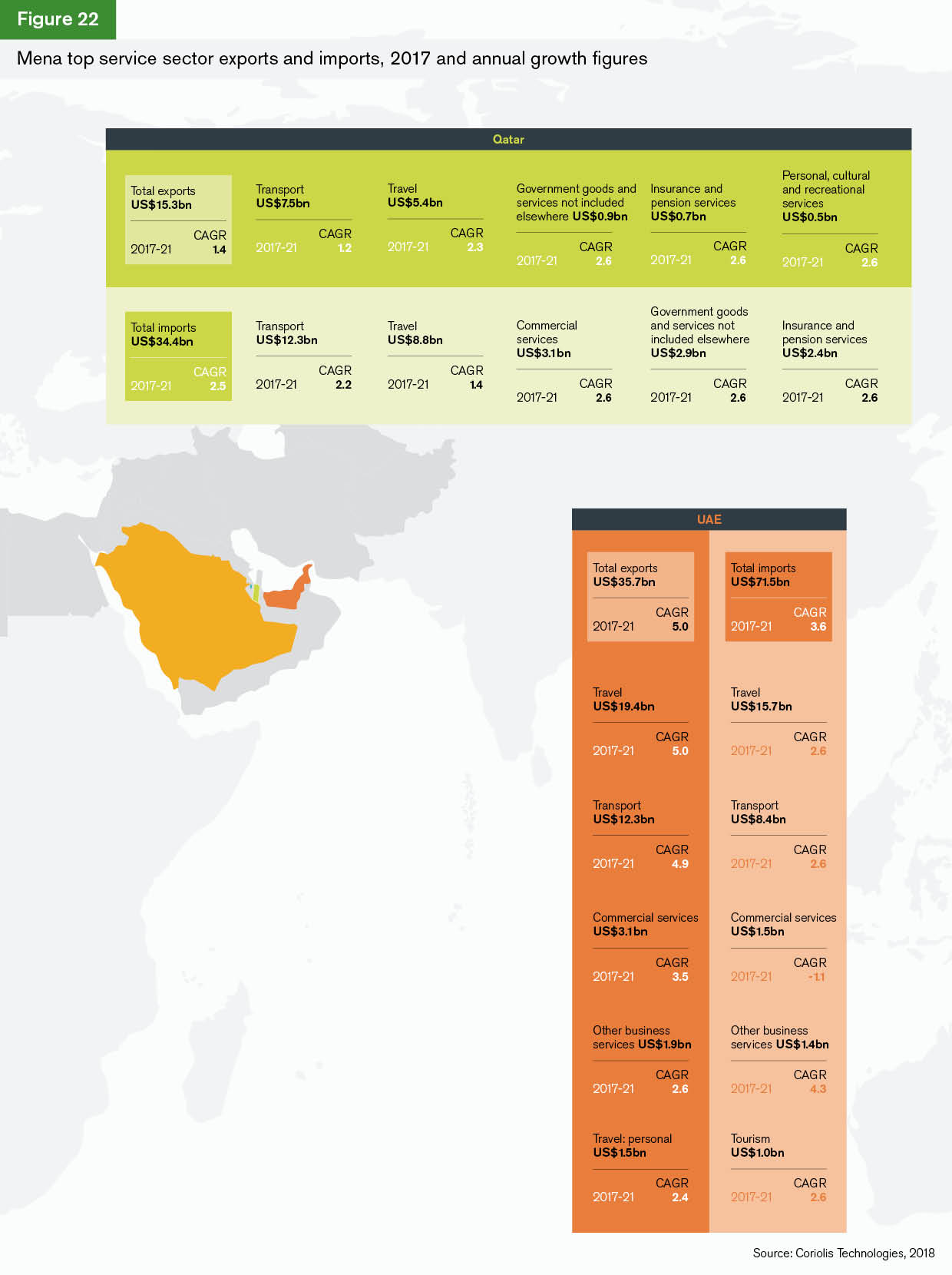

Qatar’s service sector is set to grow over the next few years. Imports will grow by 2.5% and exports by 1.4%. This may have an effect on the country’s trade position, not least because it imports more than twice the amount it exports. Transport and travel are the two biggest service trade sectors in export and import terms, which is little surprise given the country’s geographical position. Both are projected to grow. Imports of government services are also set to grow, which may suggest that the country is focusing on bringing in advisory in the form of education and public services from abroad.

Saudi Arabia is showing strong diversification through its service sector trade. Both imports and exports are set to grow, albeit from a smaller base, with export growth at 4.5%. The country has a substantial trade deficit in services, with imports five times higher than exports. The most significant growth in imports is likely to be in commercial services, with annualised growth of just under 5%, while transport exports are set to grow by around 4.3%. This could reflect a shift towards greater domestic demand for business and commercial services as well as for transport services as Jeddah and other ports grow in importance as regional hubs.

The UAE has a services trade deficit: imports are twice the level of exports. The country’s ports are well-established and, as a result, transport and travel feature strongly as import and export engines. Travel and transport exports are substantially larger than imports and are also set to grow more quickly over the next four years. Although services are a fraction of the trade values of the country’s total trade position, the dominance of travel and transport in its services trade reinforces the UAE’s position as a trade hub. The fact that commercial services exports are growing while imports are falling back also suggests that the UAE may be becoming self-sufficient in this sector.

Summary and conclusions – diversification through services?

The analysis shows a region that is economically dependent on oil and gas and affected by the drop in oil prices – even when those prices have improved slightly. This remains the challenge for the region: to either adapt to lower oil prices or to diversify away from its dependency on oil and gas. Given how resource-rich the region is in oil and gas and how poor it is in terms of the capacity to produce other products, its diversification needs to come from other sources.

Through changes in demand, the data this year suggest some diversification in imports. Pharmaceuticals and aerospace (specifically satellites) suggest that the structure of the economies is changing, with more emphasis on high-end infrastructures such as medical care, IT and security.

However, such diversification also reflects the geopolitical challenges that the region faces. While there is little evidence that conflict and blockades have deterred trade in the region, these events do little to encourage investment or certainty that overseas investors might need. The role of Russia in the region is key, and visible in statistics, while China is clearly the region’s dominant trade partner. As China’s Belt and Road Initiative beds in, the importance of both of these countries is likely to increase. Because the Mena region is a trade hub, this may bring some diversification in the exports of machinery and components to countries in Eurasia and, indeed, in India – which is also set to grow as an import partner – to support the initiative.

Service sector growth in the UAE and Saudi Arabia is strong. The region’s growth sectors are travel and transportation which is little surprise given its geographical location. In the end this is where real diversification is likely to come from.