Just as the continent seemed to be staging an economic recovery from the Covid-19 pandemic, a new shock in the shape of the Russian invasion of Ukraine is weighing on Africa’s prospects – although some bright spots remain. Eleanor Wragg examines the outlook for trade and explores some of the most interesting aspects.

After a better-than-expected post-pandemic rebound last year, economic growth in Sub-Saharan Africa is expected to stall in 2022, dropping from 4.6% in 2021 to 3.8%, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), as the global shock triggered by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine sets back the region’s prospects.

With surging fuel prices and import bills straining the external and fiscal balances of commodity-importing countries, recent progress on poverty alleviation in Africa is at risk, to the extent that the latest World Bank Global Economic Prospects report finds that it is now expected to remain the only emerging market and developing economy region where per capita incomes will not return to their 2019 levels by 2023.

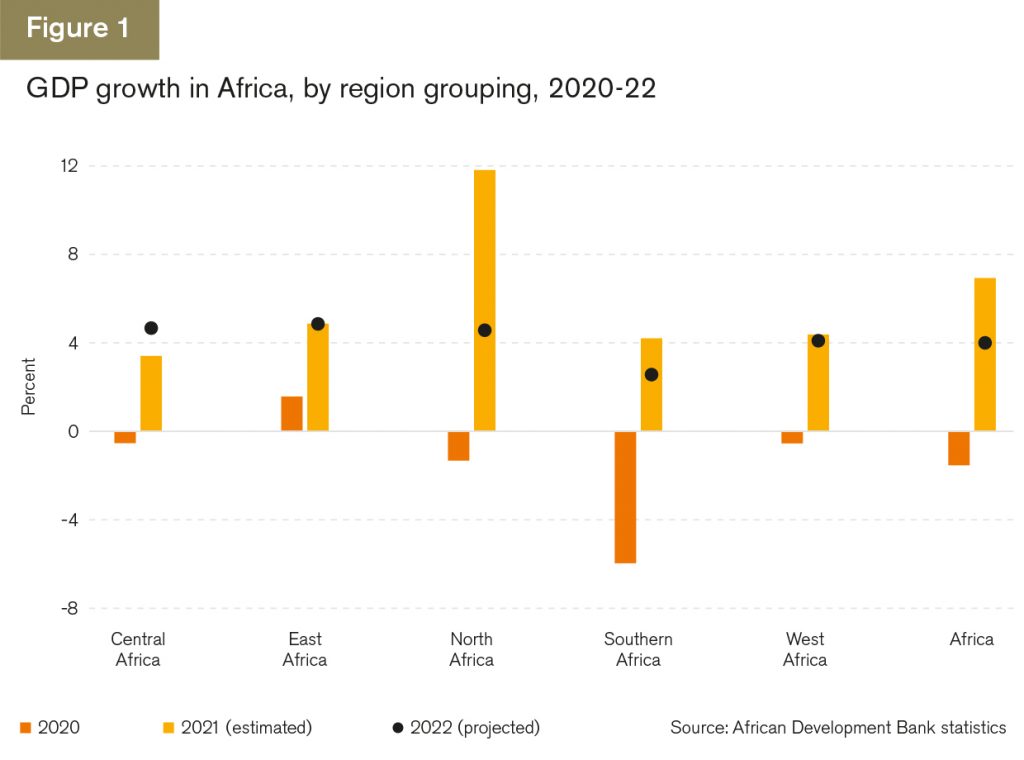

A closer look into the GDP figures reveals that economic growth continues to vary widely across countries and sub-regions – as could be expected from a diverse and heterogenous continent made up of 54 sovereign states encompassing the full range of income groups.

As figure 1 shows, North Africa staged the most impressive post-pandemic rebound, with the African Development Bank (AfDB) estimating its growth at 11.7% in 2021, largely driven by the lifting of the oil exports blockade on Libya in late 2020. Meanwhile, in East Africa – which was cushioned to a great extent against the pandemic shock by its recent economic diversification – GDP growth has been supported by public spending on flagship infrastructure projects, along with closer intra-regional trade ties and a strong agricultural performance. Meanwhile, Southern Africa, the region hardest hit by the pandemic, returned to healthy growth in 2021 after South Africa posted its highest GDP growth since 2007, which was driven by large fiscal stimuli. However, the AfDB forecasts that growth in the sub-region will decelerate in 2022 as the effects of these stimuli peter out.

“Disruptions to global trade and supply chains – primarily in agricultural, fertiliser, and energy sectors – following the Russia-Ukraine conflict and the corresponding sanctions on trade with Russia have tilted the balance of risks to Africa’s economic outlook to the downside,” says AfDB president Akinwumi Adesina in the multilateral institution’s Africa Economic Outlook Report 2022.

“The impact is, however, likely to be asymmetrical. On the one hand, net oil- and other commodity-exporting African countries could benefit from higher prices of their exported commodities. On the other, the impacts on net energy-, food-, and other commodity-importing countries are concerning as higher food and energy prices will exacerbate inflationary pressures and constrain economic activity.”

But although some sub-regions may be doing better than others, none can expect an entirely smooth ride this year.

An uneven trade rebound

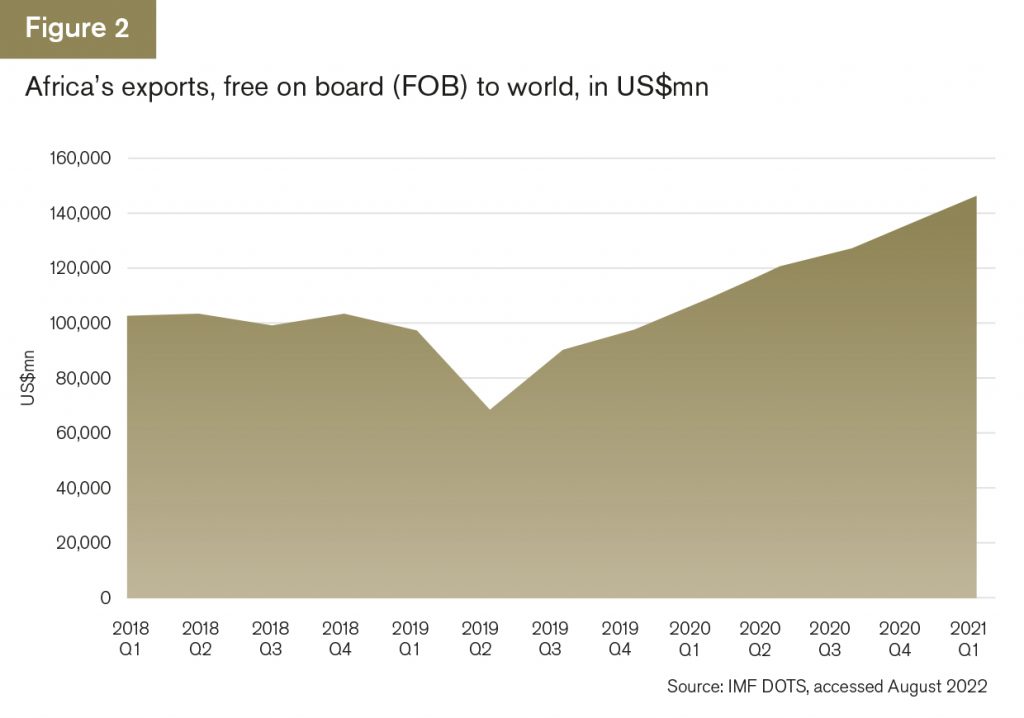

Africa’s post-pandemic trade recovery continues (see figure 2), with the IMF’s Direction of Trade Statistics (DOTS) showing that, after a sharp dip during the worst of the pandemic, exports have risen ever since, reaching US$150.1bn in the first quarter of 2022 and topping pre-Covid levels.

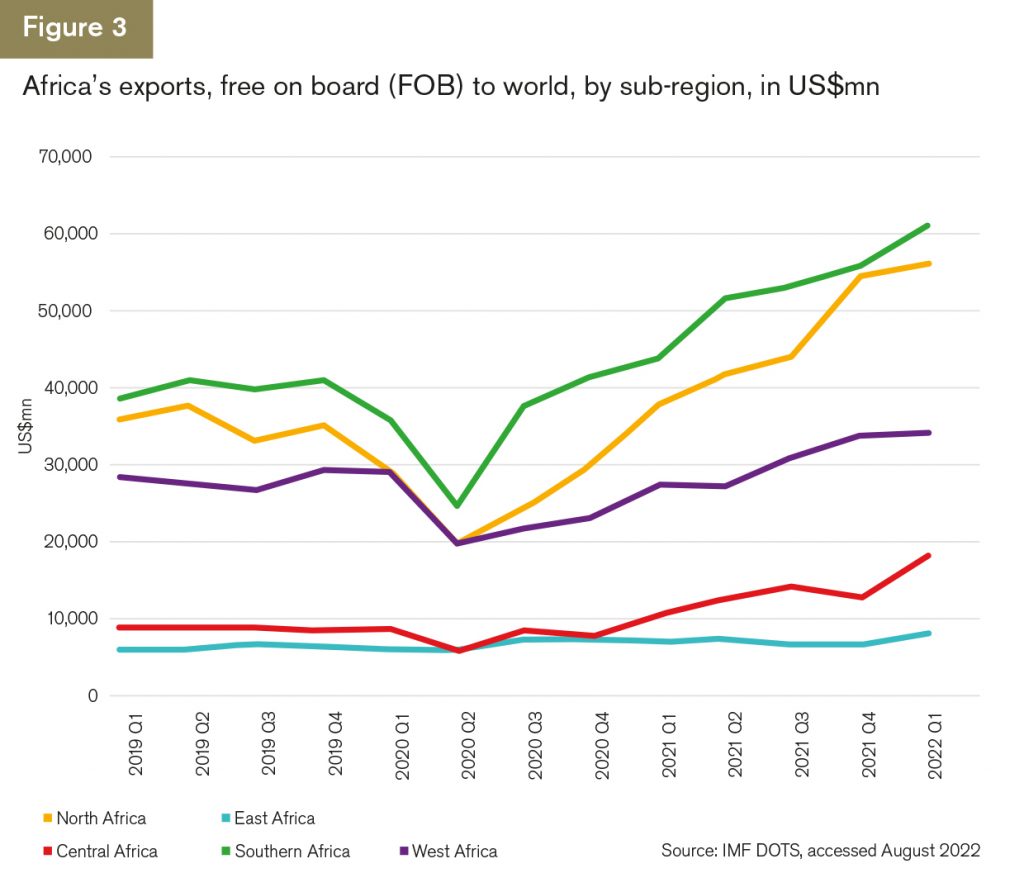

But, as in the case of GDP growth, this trade growth is not coming from all sub-regions equally. As figure 3 shows, exports from East Africa – defined by the AfDB as Burundi, Comoros, Djibouti, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Kenya, Rwanda, Seychelles, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Tanzania and Uganda – have remained relatively steady since 2019. However, at the individual country level, there are some stand-outs. Rwanda, which only accounts for 8% of the sub-region’s total trade, put on a stellar performance over the period, with an increase in exports from US$227.2mn in the first quarter of 2019 to US$695.1mn in the fourth quarter of 2021, supported by GDP growth of 7.4% in 2021.

Looking ahead, the increase in food, energy, and other commodity prices will have mixed effects for trade across Africa, with some countries benefiting while others lose out. Energy-exporting countries are poised to see gains from higher-than-expected prices, as long as they can find the extra production capacity. However, energy- and food-importing countries may struggle with inflationary pressures, compounded by disruptions in global supply chains.

Most African countries are net energy importers, meaning they export crude oil but import refined petroleum products because they lack domestic refining capacity. This overall trend puts downward pressure on the continent’s economy. While net oil- and other commodity-exporting countries could see benefits from higher prices, the negative impacts on net energy- and commodity-importing countries are likely to cancel out these gains. Meanwhile, net crude oil-exporting countries that subsidise fuel could experience fiscal shocks due to the higher price of imported refined petroleum products.

In addition, Russia and Ukraine are significant sources of raw materials such as platinum group elements, nickel, and neon gas, which are used in the automotive industry, consumer electronics, and renewable energy devices. In particular, the ongoing global shortages of these vital components may constrain vehicle production and exports in Morocco and South Africa.

Africa looks inwards

Trade under the African Continental Free Trade Area officially began as of January 1, 2021, but although the World Bank estimates it will lead to an increase in intra-African exports of 109% by 2035, several roadblocks remain to its full execution, and it is unlikely to move the needle on intra-regional trade in the near term.

“As an African myself, I’m quite used to sound policy being written and ideas being shared, but the implementation is always a challenge,” says Mukudzei Borerwe, chief operations officer at Asoko Insight, a corporate data platform for Africa. “Part of the challenge in Africa is simply dealing with the fact that the region holds 54 countries. It’s extremely diverse from a social standpoint, and also from an economic standpoint. Several countries are currently going through election cycles, and politics always comes into it, so it’s difficult to ensure that everybody’s focused on getting trade right among more local priorities.”

However, other external factors are driving a growth in intra-regional trade, says Robert Besseling, CEO of specialist intelligence consultancy Pangea-Risk.

“Covid-19, disrupted supply chains, and slowing demand for Africa’s resources in China are forcing African countries to weaken their dependence on Asia and start building up their domestic markets,” he tells GTR. “Before, you could see a large proportion of Africa’s oil and gas, in addition to many soft commodities and manufactured goods going to China, while all the manufactured goods coming into Africa were coming from China or from other markets like Vietnam. Those supply chains have taken a knock, and we’re now seeing countries with particularly diversified markets, like Kenya, boosting domestic processing and setting themselves up as hubs for intra-regional trade. They see this as a longer-term opportunity.”

A slew of export credit agency and development finance institution-backed infrastructure development projects, including a new dry bulk port in Côte d’Ivoire, the rehabilitation of the Beitbridge border post that connects Zimbabwe and South Africa, and road and rail upgrades the length and breadth of the continent, will go some way towards closing the infrastructure gap – the bane of Africans doing business within Africa, although there’s still some way to go.

“What we’re seeing now is a trend in which infrastructure is slowly being rolled out,” says Besseling. “We know there’s a big deficit still, but it is happening: there are deals all the time.”

Trade for food security

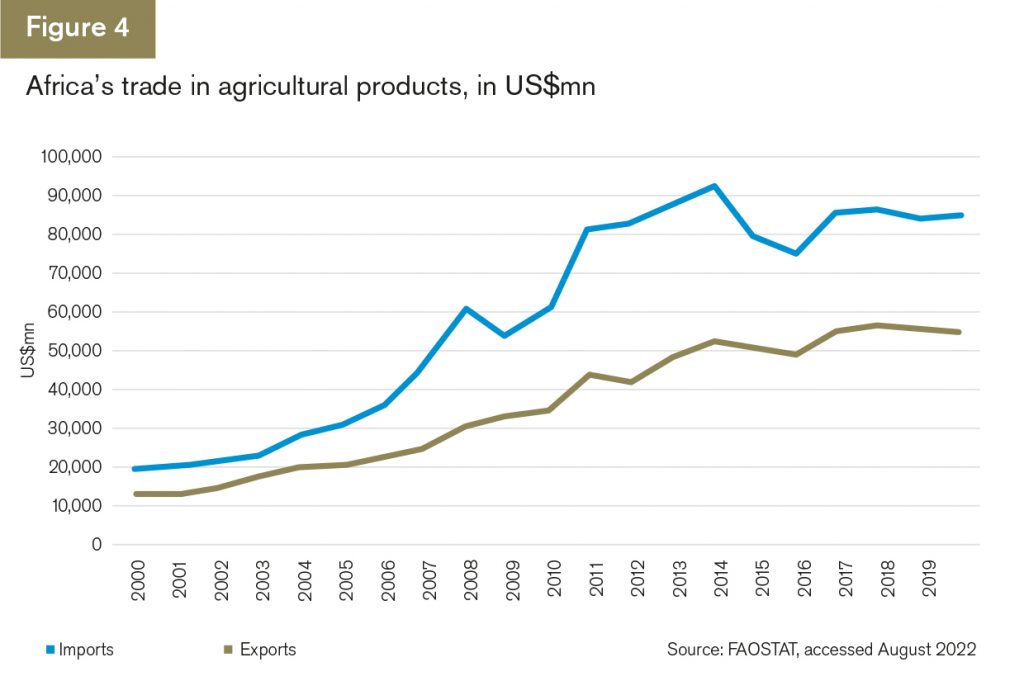

Another interesting trend is around trade in food and agricultural products. Africa both imports and exports more food than it did two decades ago (see figure 4), with lower-middle-income countries such as Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana and Kenya, becoming leading exporters of agricultural products, with a net agricultural trade surplus of more than US$5bn annually.

Despite being home to around 60% of the world’s arable land, almost half the continent depends on imports from Russia and Ukraine for more than a third of its wheat, and supply disruptions and surging prices have pushed millions of people into food insecurity.

In an attempt to tackle this issue, some African countries have put domestic price controls and export restrictions in place, such as Ethiopia, Nigeria and South Africa. Benin has enacted an export ban. Meanwhile others, like Malawi and Uganda, are offering cash subsidies to vulnerable groups.

As the crisis rumbles on, some countries are seeing an opportunity to boost local agriculture, says Besseling. “Zambia is putting money into the development of local agriculture and wheat growing – even though they’re struggling to get access to fertilisers. Ethiopia is now expecting a 70% increase in grain production this year. Meanwhile, after several weeks of nationwide protests against cereal shortages, Cameroon’s government has increased funding to grow more wheat, allocating some US$15mn, with a further US$63mn coming in from the AfDB,” he says.

Pipeline diplomacy and ESG considerations

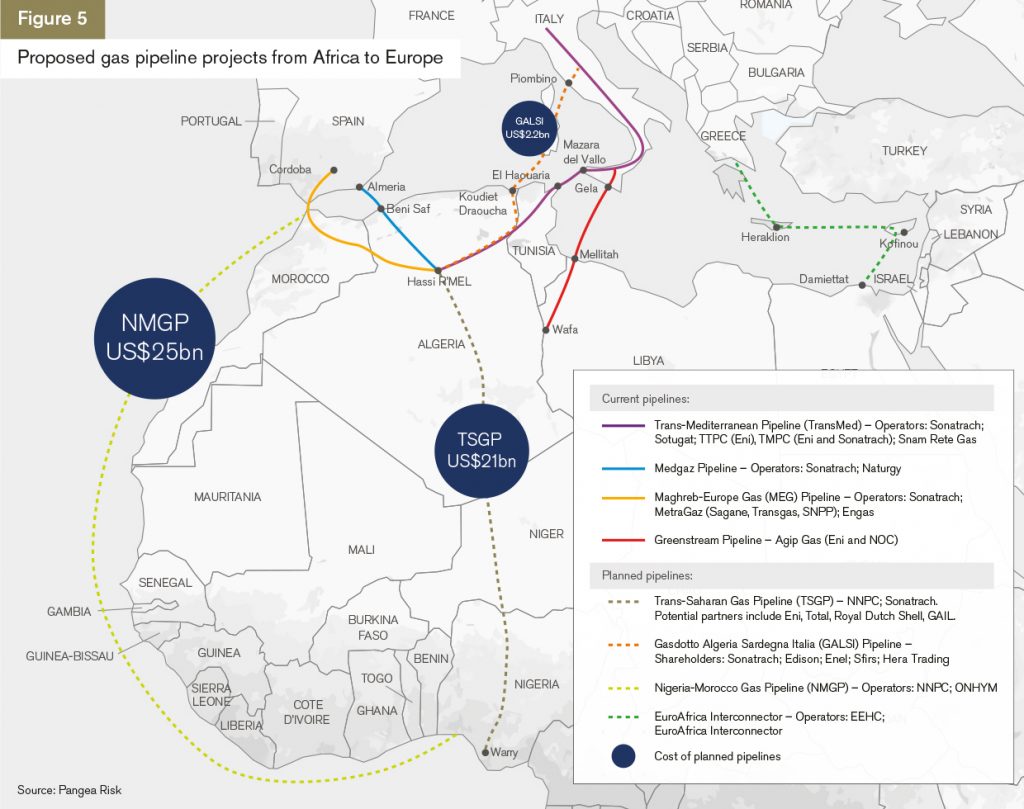

Another consequence of Russia’s war in Ukraine is its rekindling of Europe’s demand for African fossil fuels, reviving interest in projects that were previously shunned due to costs and climate change concerns. According to the International Energy Agency, Africa could replace one-fifth of Russia’s gas exports to Europe by 2030 – although that depends on whether proposed new pipeline projects (see figure 5) see the light of day.

“At least US$50bn in new pipeline investments may be signed off this year,” says Pangea Risk’s Besseling. “However, bilateral disputes and long-time Russian affiliations are complicating such efforts and European governments will need to offer concessions on food security, vaccine manufacturing, and climate change targets to secure African support.”

This last point is an important one: despite accounting for a negligible 3% of cumulative worldwide CO2 emissions historically, climate change and extreme weather events disproportionately affect Africa, with severe economic, social, and environmental consequences for its people. Moves to ramp up the continent’s fossil-fuel extraction and export industry for European consumers, especially since European demand looks likely to plummet in the coming years as investments in renewables come online, fly in the face of recent calls to halt similar projects, among them the East African Crude Oil Pipeline.

Indeed, environmental, social and governance (ESG) awareness is growing among Africa’s exporters, says Asoko Insight’s Borerwe, who says that he sees African trade as becoming more – not less – sustainable.

“There is a growing private sector focus on ESG, which is critically important from the standpoint of global competitiveness. As African companies find more opportunities to participate in global value chains, ESG scoring is becoming increasingly important. European, American and Asian multinational corporations are being held to a higher standard from an ESG standpoint, and that flows down the supply chain,”

he says. “This is all part of competitiveness, and adopting strategies and creating an environment that allows you to participate in supply chains that were previously not accessible to you.”

An uncertain future for trade

Africa’s trade outlook is an uncertain one: higher commodity prices, headline inflation and the tightening of global financial conditions are putting the continent’s productive capacity at risk.

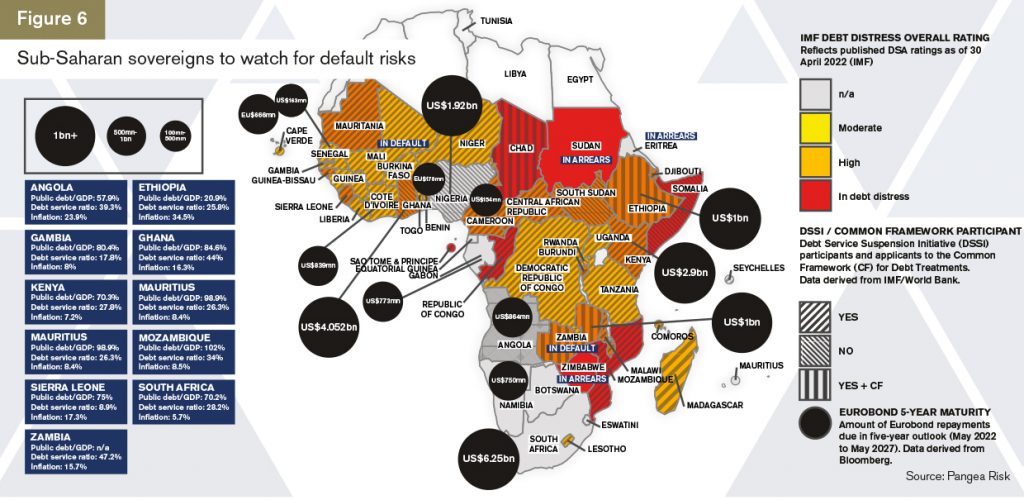

A serious downside risk to further trade growth is the growing threat of sovereign defaults. The tough global economic backdrop coupled with the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic, and food and energy shortages, all hitting at a time when countries’ policy space to respond to them is minimal to non-existent, are putting more and more countries in the region at risk of debt distress (figure 6).

“We are monitoring a number of countries, including some big trading partners across the continent, and there is a high probability for these countries to default on their sovereign debt in the five-year outlook, but some of them from 2023 onward,” says Besseling, adding that Ghana and Kenya are “very high up” on the list.

“These countries have not yet been able to recover from the pandemic-induced slowdown. Some of them may have diversified economies, but there’s simply not enough government revenue to service the debt. We’re looking at capital repayments on eurobonds that are due in the next three to five years. This is relevant to trade because the moment that a country defaults they can’t tap into international markets anymore and their trade finance facilities also disappear.”

Overall, sentiment is anything but buoyant, says Asoko Insight’s Borerwe.

“In 2021, coming off the back of Covid-19, Africa’s bounce back was as strong as anywhere else in the world, but the invasion of Ukraine has just created another challenge,” he says. “If you’d asked me, pre-invasion, then buoyancy would have certainly been the word. Business owners were looking at a new global business community in which they could participate. But we’ve all kind of taken a step back. And I think that, right now, in a lot of economies, it’s just about survival.”