As the ‘old guard’ gives way to a new generation of leaders across the continent, geopolitical risk is becoming more nuanced both within and between countries. Previously closed economies are opening up to foreign investment and opportunities are growing faster than the inflow of funds to sustain them. Elizabeth Stephens, founder of Trendline Analytics, takes a fresh look at Africa from the traditional investment destinations of Nigeria and South Africa, to the emerging markets of Cameroon and Ethiopia.

The past year has been one of leadership change across Sub-Saharan Africa and with two of the continent’s longest-serving ‘old guard’ leaving office, new investment opportunities are emerging. The importance of gaining a clear understanding of the impact of political transitions on the investment environment is once again apparent.

In Angola, after 38 years in power, President Jose Eduardo dos Santos has been replaced by João Lourenço. Observers who expected business as usual were in for a surprise. Lourenço launched a crusade against corruption and targeted many of his predecessor’s appointees who had held powerful roles in state businesses and institutions, including dos Santos’ son and daughter.

In Zimbabwe, it was a case of the former secretary bringing down the president, when a military coup deposed Robert Mugabe in November 2017, after 37 years in power, to prevent his wife, Grace, succeeding him.

Ethiopia is now home to the continent’s youngest leader. 41-year-old prime minister Abiy Ahmed won the general election on June 24. He is standing on a platform of institutional and economic reform and is opening state-owned companies such as Ethiopian Airlines and Ethio Telecom to foreign investment.

Investors are eagerly awaiting elections in the Democratic Republic of Congo and the potential for a change of leadership is high as the incumbent President Joseph Kabila’s term expired in 2016. The mineral-rich country is Africa’s largest by landmass and is marred by political violence, which is exported across its borders. A lack of clarity around Kabila’s intentions could see the elections pushed into 2019 and a further rise in instability.

Nigeria and South Africa are the continent’s biggest economies and their leadership is a cause of political uncertainty. Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari is afflicted by illness causing speculation as to whether his health will allow him to complete a second term in office were he to win the 2019 presidential election. In South Africa, Cyril Ramaphosa, who was narrowly elected president following the ousting of Jacob Zuma, must deal with the legacy of cronyism and nepotism. Corruption may well escalate in the run-up to the 2019 general election as Zuma’s associates maximise what may be their last opportunity to profit from their positions.

Old challenges reappear

Across Sub-Saharan Africa, businesses may be impacted by a renewed sovereign debt crisis, as the risky affair with eurobonds looks likely to end badly. The region’s countries sought funding from the bond markets when bilateral loans and grants from the western and eastern blocs dried up in the wake of the global financial crisis. A dozen countries have racked up eurobond debt of more than US$23bn that carries an average annual coupon payment of approximately US$1.7bn.

Dependence on uncertain commodity prices to fund high levels of external debt are stoking fears of a renewed sovereign debt crisis. Debt servicing costs, particularly for oil-producing countries, absorbed more than 60% of government revenues in 2017.

Senegal and Ghana have been issued bonds to refinance outstanding bonds, while Zambia is seeking a US$1.6bn bailout from the IMF. Mozambique had its budget support pulled by the IMF last year when it emerged that the government had lied about its debt position.

Investment opportunities

As cash-strapped governments court foreign investors, trade and investment opportunities are plentiful. The majority of the region’s population are under 25 years of age, providing a workforce and consumer base. The continent is rich in natural resources, from water and fertile agricultural land to metal and mineral deposits. For companies operating and investing in the region, protecting reputations and understanding what may compromise it is crucial.

Agriculture

Agriculture is an untapped investment opportunity and has the potential to become a great driver of growth over the next decade. Sub-Saharan Africa is home to 60% of the world’s uncultivated land and has an abundance of poorly managed water resources. Ethiopia has some of the most fertile arable land in the world and actively encourages foreign investment, as does neighbouring Sudan.

Power

Africa is home to over half of the world’s renewable energy potential and the opportunities for investment are vast. Economic growth and the ability to sustain increasingly urban populations are dependent upon electrification, which host governments lack the financial resources and technology to manage themselves. Approximately 80% of the East African region is without electricity, whilst in West Africa, almost 90% of Liberia’s population has no access to reliable electricity as compared with 55% of Nigerians.

Retail

With the region’s young population, the opportunities for the retail sector are abundant. Nigeria, Ethiopia and the Democratic Republic of Congo have the most favourable consumption spending growth, stemming from their large population growth rates. Many young people are already addicted to shopping online, whilst for consumers in Ghana, Kenya and Nigeria, visiting shopping malls combines a social occasion with consumerism.

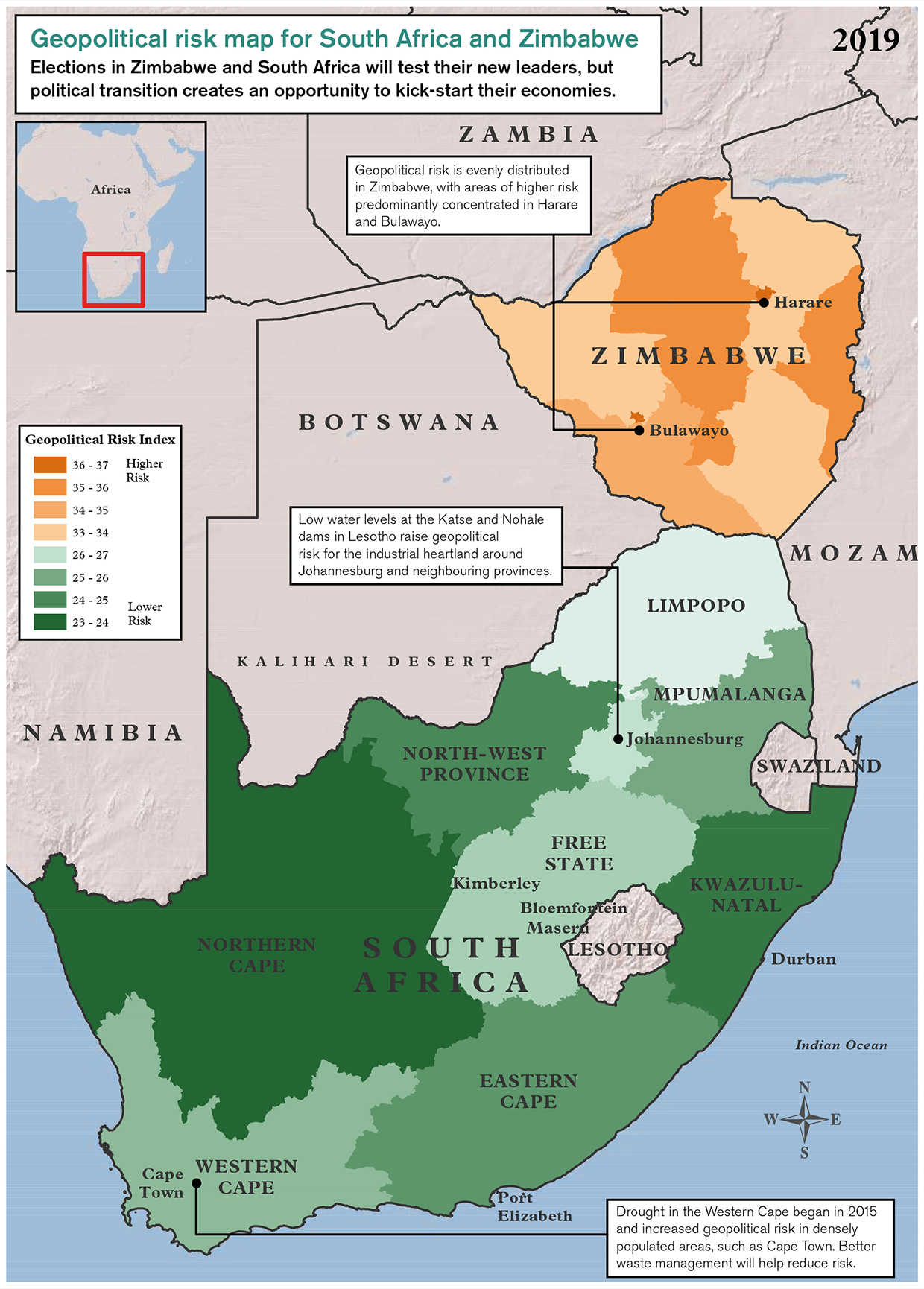

South Africa and Zimbabwe

Within the space of three months, the presidents of South Africa and Zimbabwe were forced by their own parties to resign from office and the new leadership must now face their electorate.

In November 2017, Robert Mugabe was ousted from power after 37 years, in a military coup supported by the vast majority of the 17 million population. The interests of the military and population at large converged in their dislike of Grace Mugabe and their determination to prevent her from succeeding her husband to the presidency.

While the presidency of Emmerson Mnangagwa is being heralded as a new beginning, the opposition MDC is sceptical that the change of ZANU-PF figurehead will translate into a free and fair election on July 30, 2018. There are claims of serious problems with the electoral roll and concerns over the ballot papers, a biased election commission, systematic intimidation of voters in rural areas and bias in the dominant state-run media. Mnangagwa has pragmatically recognised the need to win international legitimacy if his country is to access the financial assistance it so desperately needs, but it remains far from certain that they would step aside were MDC to win.

In December 2017 Cyril Ramaphosa, a billionaire businessman and long-time ally of Nelson Mandela, was elected as the leader of the ruling African National Congress (ANC) and in February 2018 as the country’s president after Jacob Zuma was forced to resign amidst allegations of corruption. Zuma’s removal was not as widely supported as his Zimbabwean counterparts, and a power struggle continues within the party between Ramaphosa’s supporters and those who remain loyal to Zuma. The infighting is constraining the new president’s room for manoeuvre and popular disaffection with the pace of reform is growing. This should be cause for concern for the ANC, which must contest elections next year in the first general vote since 2016, when the opposition won control of several key municipalities including Johannesburg and the capital, Pretoria.

Ramaphosa enjoyed an early success in March, when Moody’s maintained South Africa’s investment grade rating in response to pledges by the president to privatise stakes in state-owned companies. Yet after an initial resurgence, the rand has fallen in value and the country is being buffeted by external forces, such as rising US interest rates, which are impacting developing markets.

In June, ‘load-shedding’ returned to bedevil South Africa as strikes over pay forced Eskom, the state electricity monopoly, to cut supplies. The power cuts are an embarrassment to Ramaphosa and bring new urgency to his pledge to overhaul the state-owned groups that dominate the country’s industrial base. If the power shortages persist, they will act as a constraint on economic growth.

Cape Town, South Africa’s second-largest city, narrowly postponed ‘day zero’ this summer, a moment when dam levels would be so low that taps would be turned off and people sent to communal water collection points. Massive investment is needed in water conservation and infrastructure projects and restrictions on water usage are having a profound impact on the agricultural and wine growing sectors.

While South Africa’s infrastructure creaks, Zimbabwe’s is crumbling. The economy is in desperate need of capital. Millions rely on food aid, government employees go unpaid and government debts have soared. The country’s natural resources offer tremendous opportunities if the government can convince investors it is a reliable partner. The UK is interested, needing a foreign policy success as it negotiates Brexit. The CDC, the UK’s development financial institution, has teamed up with Standard Chartered to lend US$100mn to Zimbabwean companies in what will be the British government’s first direct commercial loan since 2001. A list of companies that can access loans is being drawn up and is expected to focus on the food processing, manufacturing and agricultural sectors. Large-scale UK investment is dependent on a free and fair election.

Meanwhile, China continues to take advantage of the Trump administration’s lack of interest in Africa and will invest even more when the financial and legal systems improve. The multilateral lenders cannot supply the money required to refloat the economy until massive loan arrears are cleared.

Private investors are proving willing to test the waters with relatively small investments. Tharisa, a London-listed chrome producer, has paid US$4.5mn for a stake in a platinum resource in Zimbabwe’s Great Dyke. The land was released for investment in an effort to attract foreign investment into the mining sector.

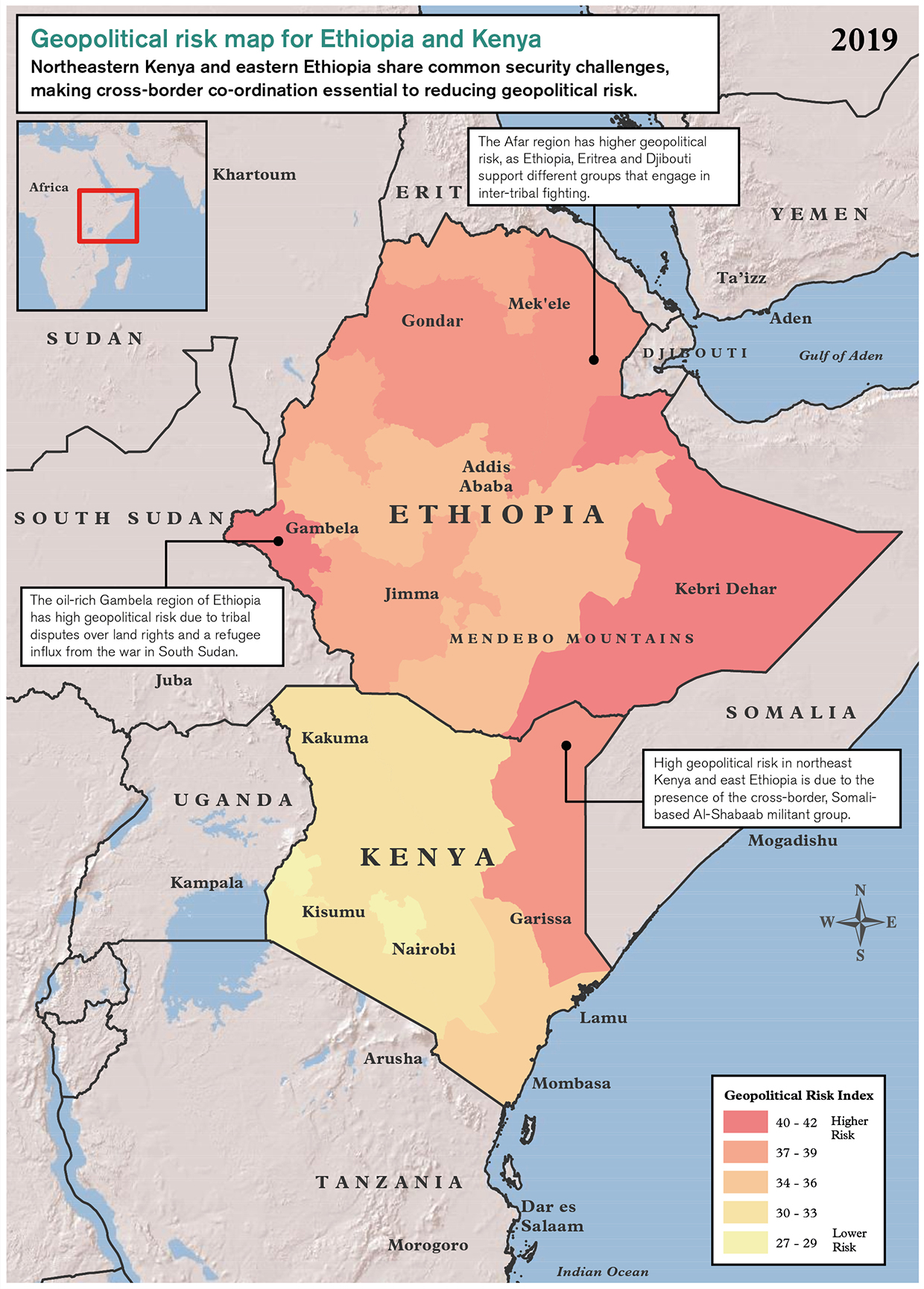

Ethiopia and Kenya

Political protests and elections are shaping the investment landscape in Kenya and Ethiopia in contrasting ways. Kenya’s status as the democratic success story of East Africa is rapidly fading, whilst Ethiopia is in the ascendancy.

A series of investment reforms have been announced by Ethiopian prime minister Abiy Ahmed, who took office in April following the resignation of his predecessor after three years of anti-government protests threatened the regime’s 27-year grip on power. Ahmed has announced his intention to reform state-owned conglomerates that dominate the economy and permit foreign investment in Ethiopian Airlines and Ethio Telecom. Opportunities in sugar, hotels and industrial parks may follow.

At 41 years of age, Ahmed is Africa’s youngest head of state, and the first leader from the Oromo region to hold the position of prime minister. The Oromo comprise one-third of Ethiopia’s 105 million people but have been politically and economically marginalised by the historical dominance of the Tigrayans. Following the release of many prominent political dissidents and the dropping of terrorism charges against activists who fled abroad, Ahmed is riding a wave of popularity. He has bought the regime some precious time, for now.

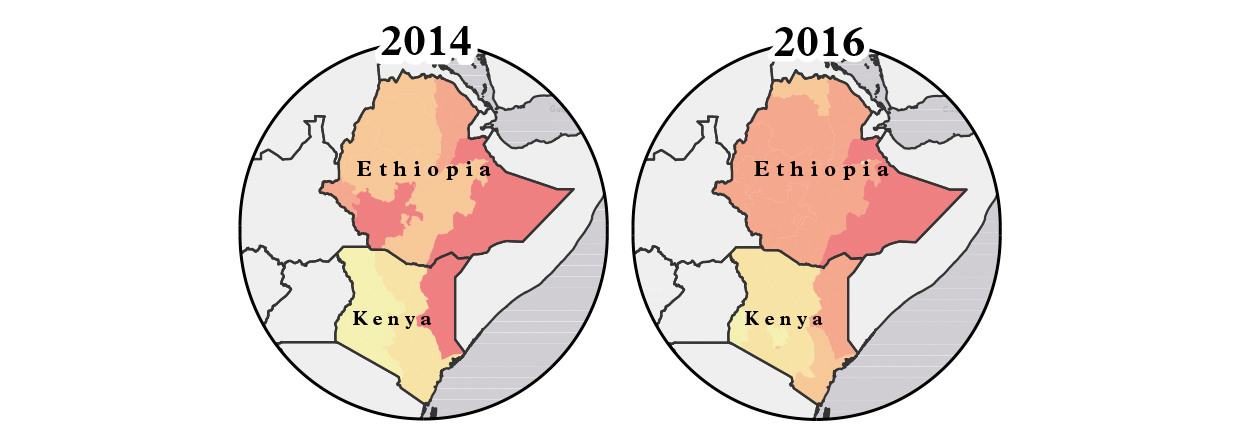

While Ethiopia is witnessing an improvement in political legitimacy, Kenya is experiencing the reverse. Accusations of electoral irregularities undermined the legitimacy of the 2017 presidential poll and the rerun, controversially ordered by the supreme court, was marred by violent clashes between security forces and protestors. Incumbent President Uhuru Kenyatta was declared the victor though a 38% turnout as a result of the opposition boycott, reflecting a high level of ethnic marginalisation.

The disputed election caused geopolitical stability to deteriorate at a fast rate, although it remained consistent with the overall trend for the country. The correlation between elections, economic downturns (seven of the previous 10 elections have triggered an economic contraction) and political violence were reinforced.

A continuing drought is damaging Kenya’s agricultural production, a sector on which the economy is highly dependent. Agricultural production, particularly tea and horticulture, provides 60% of employment, including subsistence farming and is the primary generator of foreign exchange.

Kenya’s industrial sector is performing well and is driven by strong public investment in infrastructure and the relatively strong manufacturing base. Infrastructure development has been identified by the government as the driver for increasing competitiveness and offers opportunities for overseas construction companies to tender for projects.

This strategy has met with success in Ethiopia, where government-led, debt-financed spending on roads, railways and dams has generated average growth rates of 10.3% over the past decade. Ethiopia has now embarked on the largest infrastructure project on the continent. The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam is a US$4.8bn hydropower project that will be the largest in Africa and a linchpin of Ethiopia’s plans for economic development. While the dam will take five to 15 years to fill, the electricity produced will feed into the national grid and contribute to the electrification of the country. Excess power could be sold to neighbouring Sudan and Djibouti, generating foreign currency reserves.

The dam is already raising geopolitical tensions. Ethiopia is adamant that the dam will not adversely affect downstream countries once the 74 billion cubic metres (bcm) reservoir has been filled, though it has refused to officially recognise what Egypt considers its right to 55.5bcm of water every year. This volume is specified under a 1959 agreement between Egypt and Sudan to which Ethiopia was not a signatory. The potential for conflict between Egypt and Ethiopia over access to the Nile waters is high.

Ethiopia’s external challenges are exacerbated by its location in a high-risk neighbourhood, sharing borders with Sudan, South Sudan, Eritrea and Somalia, which export their internal instability. Geopolitical risk is elevated in the Afar region because Ethiopia, Eritrea and Djibouti support different rebel groups that engage in inter-tribal fighting. The oil-rich Gambela region of Ethiopia has high geopolitical risk due to tribal disputes over land rights and a refugee influx from the war in South Sudan.

Lawless Somalia continues to present a security challenge to Kenya and Ethiopia, for which cross-border co-ordination is essential in order to contain. The activities of Islamic militant group Al-Shabab increase geopolitical risk in north eastern Kenya and east Ethiopia, impacting economic activity, whilst the fear of kidnapping has triggered a reduction in tourists.

Nigeria and Cameroon

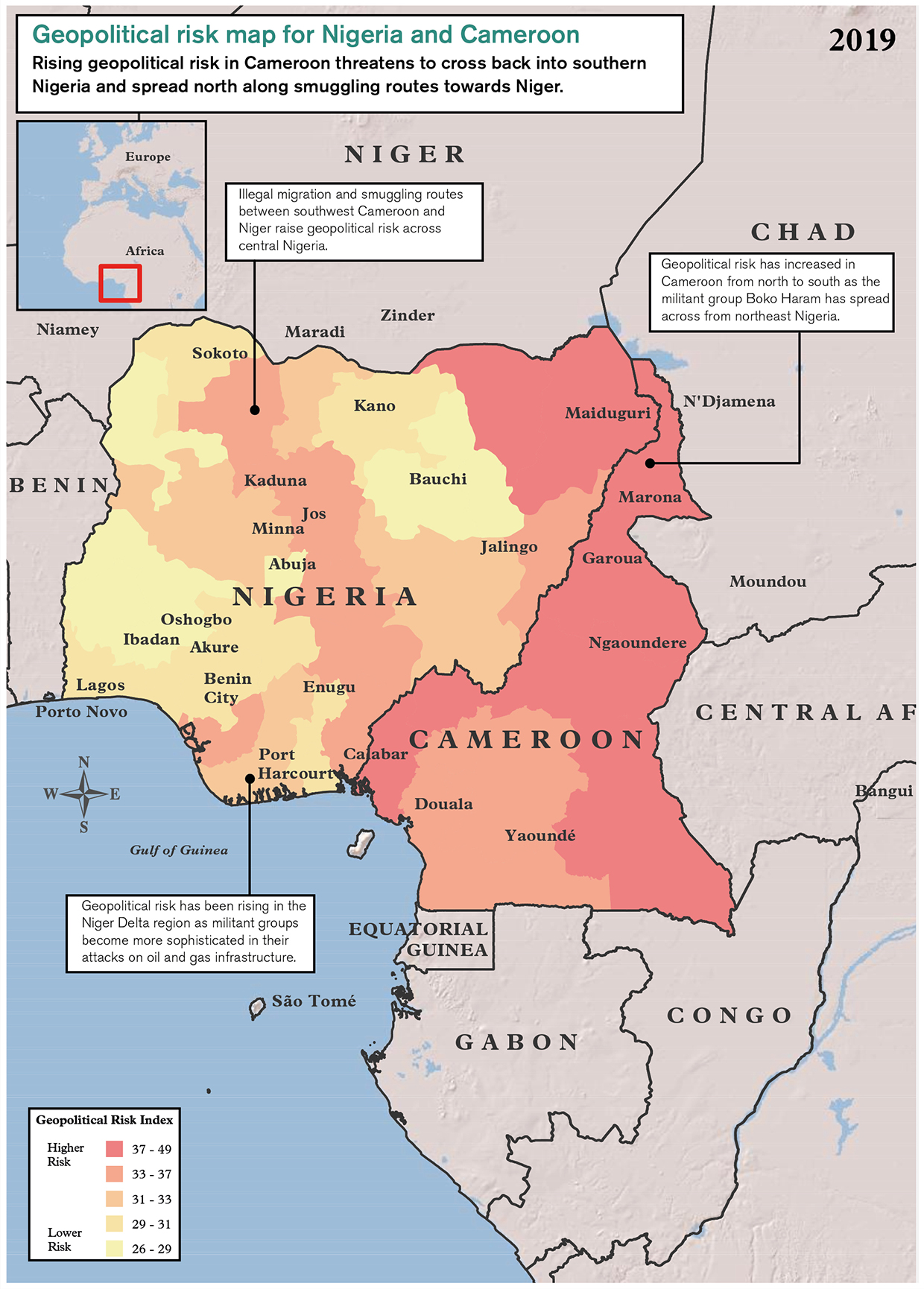

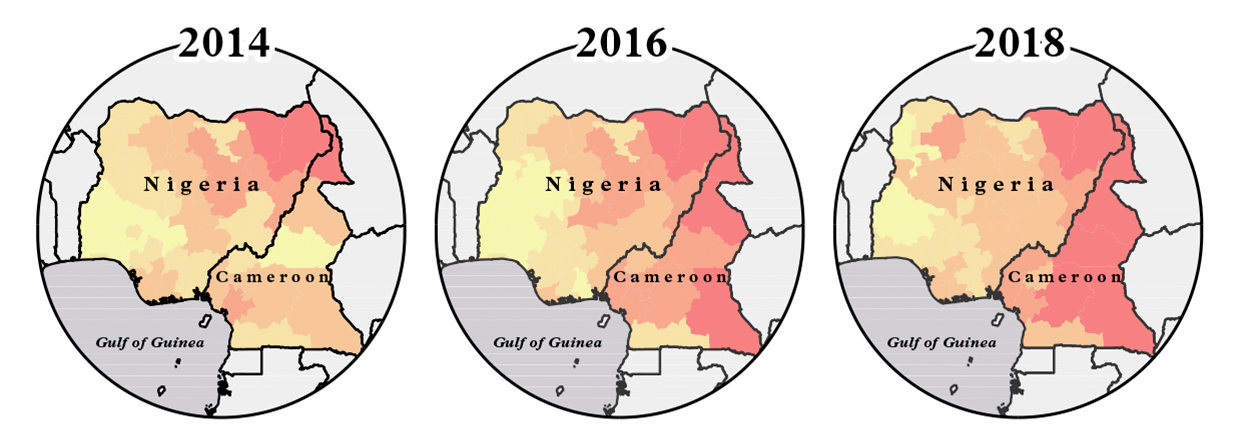

Geopolitical risk in Nigeria and Cameroon are intertwined as porous borders and the absence of a co-ordinated counter-terrorism response allow the militant Islamic group Boko Haram to move seamlessly between the states. Aggressive action by the Nigerian army in the run-up to the 2015 presidential election forced Boko Haram into the border region with Chad and Cameroon and since then geopolitical risk has increased in Cameroon from north to south as the group’s activities have spread.

This destabilising impact has coalesced with the struggle against militias from the Central African Republic to the east and calls for succession amongst elements of the Anglophone population in the southwest and northwest. Cameroon has the unusual history of a British and French colonial legacy and since the unification of the country in 1961, English-speaking Cameroonians have a fraught history with the French-speaking majority. The brutal government response to peaceful protests that reignited in 2016 against the dominance of the French language and the subsequent escalation of violence have culminated in fears of a full-blown secessionist crisis. The potential rout of the ruling party in presidential elections scheduled for October 2018 increases the stakes.

President Paul Biya, the 82-year-old who has ruled the country for 35 years, shows no sign of leaving the political stage. Despite the relative diversity of the economy compared with other oil-producing states, the lack of viable employment opportunities is a combustible source of discontent amongst a young population who view their aging president as out of touch and unable to meet their aspirations. 60% of the population in Nigeria and Cameroon are under the age of 25. The enduring resilience of a regime that retains power through intimidation and coercion creates the illusion of political stability but the current security and political constellation increases the potential for crisis.

The credit rating agencies are already expressing concern about Cameroon’s political climate, and a further deterioration in the security environment could lead to a downgrading of its sovereign credit rating at a time when the country is already under IMF adjustment measures.

Nigeria, too, is potentially facing a sovereign debt crisis. High levels of external debt, dependency on fluctuating commodity prices to fund repayments and borrowing to fund recurrent expenditure exert significant pressure on the sovereign rating. The 2018 budget proposes to use US$6.1bn for debt servicing, up from US$4.5bn in 2017.

Prudent economic management is likely to be in short supply in the run-up to Nigeria’s presidential election scheduled for February 2019 as millions of dollars will be required to finance the election campaigns. President Muhammadu Buhari has already announced that he will run for re-election, which settles that question rather than allowing uncertainty surrounding his intentions to continue. Given his health condition, his decision to run was not a given, and were he to pass away whilst in office, a political crisis over succession could ensue.

The 2018 budget is expansionist and seeks to increase expenditure on infrastructure and new housing, reflecting a belated effort to appease voters dissatisfied by Buhari’s investment record. The spending plans are heavily dependent on stability in the oil-producing Niger Delta, which is maintained, at present, by government stipends to former Delta fighters. Stability is far from assured and, as the maps show, geopolitical instability can be seen moving through Cameroon and back into the Niger Delta, as the region’s wealth attracts the attention of domestic militant groups and trans-national terrorist organisations. Militant groups are becoming more sophisticated in their attacks on oil and gas infrastructure and geopolitical risk in the Niger Delta is increasing. Illegal migration and smuggling routes between southwest Cameroon and Niger that traverse Nigerian territory also raise geopolitical risk across the country and continue to flourish.

Meanwhile, new investment opportunities are being created and Nigeria’s fledgling mining sector offers one such opportunity. Investment in Cameroon’s offshore gas projects and hydroelectric potential offers others. Investors will need to assess the ability of the government to effectively manage and regulate these industries and the associated risks that may be created, spanning corruption to environmental impact and disruption to local communities.

About Trendline Analytics

Trendline Analytics helps businesses identify and manage their geopolitical risk. It uses over 100 million data points to track and forecast geopolitical risk for more than 1,500 territories across the world. Fusing the latest mapping technologies with big data analytics, it enables companies to develop strategies that manage geopolitical risk wherever they choose to do business.

Dr Elizabeth Stephens founded Trendline after seeing the huge competitive advantage that big data offers in understanding how global events impact investment returns. Today, Trendline’s single focus is to redefine how companies manage geopolitical risk to give them the advantage in an uncertain world.