The Great Green Wall project in Africa’s Sahel region offers a potentially attractive opportunity for sustainable investment. But the risks of political corruption and growing insurgent groups mean that supporting the initiative, in some cases, is a near-impossible task, writes Maddy White.

In January, French President Emmanuel Macron announced that development banks and states, including the French government, the African Development Bank (AfDB) and the World Bank, had pledged US$14.3bn in fresh funding for the Great Green Wall (GGW) initiative in Africa’s Sahel region.

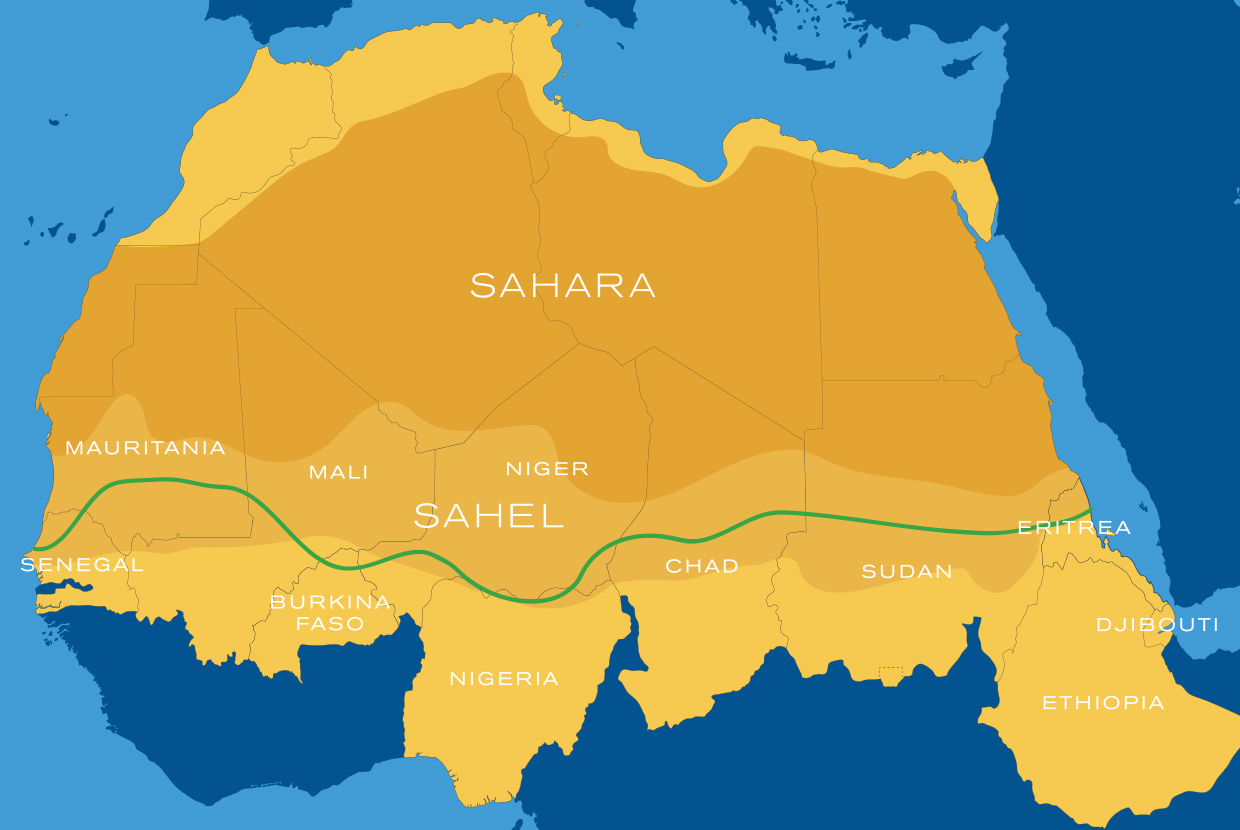

The GGW was launched by the African Union (AU) in 2007, initially aiming to create an 8,000km-long and 15km-wide vegetation barrier that would snake along the Sahel and halt the expansion of the Sahara desert. But in recent years, the vision has evolved to include different land use and production systems that encourage more general sustainable development across the continent, east to west.

“As we rebuild from the coronavirus and its impacts on our world, we must recalibrate growth,” AfDB president Akinwumi Adesina said at the time of Macron’s announcement. “We must prioritise growth that protects the environment and biodiversity, and we must de-prioritise growth that compromises our common goals.”

The initiative is managed by the Pan-African Agency of the Great Green Wall (PAGGW), an inter-governmental organisation overseen by the AU that comprises the heads of state of the 11 countries involved in the project: Burkina Faso, Chad, Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal and Sudan.

Progress on the wall has thus far been slow. In 2015, the goal of the GGW as stated by the AU was to restore 100 million hectares (Mha) of degraded land by 2030. This target was later revised to 25 Mha, according to a 2020 status report on the project by the United Nations (UN). In terms of the amended aim, only 16% of that goal has been reached – and with a mixed success rate in the key countries.

One of the reasons for this lacklustre advancement has been the failure to secure the private and public funding needed for the project’s realisation. From 2011-19, key financiers of the initiative included the World Bank, through its Sahel and West Africa Program, the UN Food and Agriculture Organization, and the European Union under the UN’s FLEUVE project. Funding for projects reported by international donors totalled US$870.3mn for this period – a meagre slice of the US$33bn overall cost of the GGW.

But, going forward, the AfDB stated in January that the Sahel is a “top priority” for investment and mobilising new sources of finance to advance Africa’s environmental, social and governance (ESG) opportunities and support local communities.

Robert Besseling, founder and chief executive at Pangea-Risk, a specialist intelligence company, tells GTR: “Things had stalled, and that is understandable in terms of the lack of interest from DFIs and impact investors in a region which is quite restive, quite politically unstable, suffers from frequent insecurity and is, apart from areas in the east and west, almost completely landlocked.

“Why we are talking about it more and more now is because France in particular, with a traditional historical base in the Sahel, has been pushing the Great Green Wall and has been able to secure funding for it. That gives quite sizeable opportunities for Sahel-based ESG investment projects.”

An unstable backdrop

Despite there being the potential for investment, Besseling says it is too early to tell whether or not private investors will allocate capital to the GGW.

“First of all, we need to see the new money pledged being disbursed. We need to see it going to new projects and not being used in projects that already have capital assigned – because that has happened with this initiative before. And, of course, that money needs to be invested in projects which make a direct impact in terms of the ESG goals for the region. It is extremely important to make sure it is not embezzled by governments or used for political purposes.”

The Sahel has been plagued by government corruption in the past. A military coup in Mali last year saw the ruling party overthrown by the army, following protests that called for the resignation of then-President Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta over alleged graft scandals and his handling of insurgent groups and the economy. In Chad, President Idriss Déby has faced many allegations of corruption and bribery since his presidency began in 1990. In general, Sahelian states have persistently scored poorly on Transparency International’s annual Corruption Perceptions Index.

As well as the high possibility of political corruption, the Sahel is an area roamed by militant parties, including Islamist insurgent groups. That creates significant reputational, disruption and asset risks associated with doing business in the region.

In July 2020, Mohamed Ibn Chambas, head of the UN Office for West Africa and the Sahel, said that despite efforts by concerned countries, violent extremists continue to attack security forces and civilians, forcibly recruiting children into fighting in Burkina Faso, Mali, Niger and Nigeria.

Burkina Faso’s government said in February this year that it was open to holding talks with Islamist militants to try to end escalating insurgencies. A similar approach was taken by officials in Mali last year before the coup, with violent conflict having continued in the country since militants briefly seized control of northern Mali in 2012. In Niger, deadly attacks by suspected jihadists on two villages killed 100 people at the beginning of January.

Soon after the Niger attack, Macron indicated that France would reduce the number of soldiers on the ground in Sahelian states after years of army operations. French forces, which have been leading a coalition of allies against Islamist factions in the Sahel, had in 2013 defeated those that seized power of northern Mali, but have since struggled to suppress growing Islamist powers in the region.

“If you want to make a useful impact, you have to think that if there are still terrorist groups after seven years, that means they are embedded and your problem is not simply one of security. It’s a political, ethnic and development problem. So at that point, I will adjust our contingent,” said Macron, as reported by the Financial Times.

Elizabeth Stephens, managing director of Geopolitical Risk Advisory, a geopolitical technology company, tells GTR that while there is interest in building solar power farms and other ESG projects across cities in the Sahel, there are fears on the part of foreign investors around the ability to effectively protect assets from jihadists.

“ESG and development projects to improve the lives of local people require a speed and scale that outstrips that of jihadi activities, and that is not happening at present. It is unlikely that it will,” she says.

Elsewhere, in the east of the Sahel, other conflicts have surfaced. The Tigray People’s Liberation Front has been battling the Ethiopian government in the northernmost region of the country since November. Eritrean forces are reported to be involved in the conflict. Red Cross Ethiopia, a humanitarian organisation, has warned of severe food insecurity for the people of Tigray.

More than a wall

Despite significant instability, there is some investment in the region and support of local businesses.

In partnership with the US International Development Finance Corporation, the US Agency for International Development (USAID)-funded West Africa Trade & Investment Hub announced its first project with international development organisation Cordaid in January. Managed by Cordaid’s investment arm, the scheme aims to boost access to finance for SME and microfinance institutions in Burkina Faso, Mali, Guinea and Sierra Leone.

The partnership will mobilise up to US$37mn of new private investment into these countries, creating more than 20,000 direct and indirect jobs and increasing the value of exports substantially, according to a joint statement.

Elsewhere, in late January, the European Investment Bank confirmed €38.5mn in new financial support to expand the capacity of a solar power plant in Burkina Faso operated by the national electricity authority Sonabel.

But while there are opportunities in the Sahel for mobilising finance and ESG investments to encourage development, “the idea of investing equitably across the whole Sahel seems unrealistic”, says Besseling. Rather, focus will be given to a few key areas that are both feasible and bankable.

“If it is a large solar power facility backed by a DFI and an export credit agency in a relatively stable part of a country in the Sahel, there could be some good returns. But not all the projects in this initiative would have that type of return on investment and backing. Not many investors will be willing to do business in parts of Burkina Faso, Mali or Sudan, and you won’t find insurance.”

Meanwhile Stephens says that if security could be guaranteed, the Sahel would be “ripe” for projects. “The consensus is that if the Great Green Wall initiative were successfully completed in a five-year timeframe that could be the beginnings of a game-changing situation for the region.”

Those supporting the GGW are intent on its success, viewing it as a new start for the Sahel and more than just a wall of trees. But the confidence of investors around the initiative is marred by the increasing instability in the region, and whether or not their funds are even safe. How the recent money pledged is distributed will be key to the success or failure of the project.