Located half a world away from China, Latin America isn’t an obvious component of the Belt and Road Initiative, which follows the path of the historic Silk Road from Asia to Europe. But as the Asian giant continues to expand its ambitious project, it is reviving another ancient trade route which once linked it with the Americas. With this comes the emergence of two unlikely Latin American gateways to Chinese trade, writes Eleanor Wragg.

Between 1565 and 1815, the Manila galleons sailed across the Pacific Ocean, carrying the silk, spices and porcelain of Chinese merchants from the Philippine capital to what is today Mexico in exchange for silver. Much as the silk route linked China with the economies to its west, for 250 years the Manila galleon trade route provided it with an eastward link to the Americas. Today, as China expands its continental European ‘belt’ and Asian and African maritime ‘road’ initiative to include the geographically distant Latin American region, the Manila galleon route looks set to undergo something of a revival.

Now officially in Latin America since a meeting of the China-CELAC (community of Latin American and Caribbean states) forum in Chile in 2018, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has seen cautious take-up by countries in the region. The first to formally declare its membership of the Chinese development strategy was Panama, which signed up in November 2017, just after it opened diplomatic ties with the Middle Kingdom after ditching its long-term support for Taiwan. Since then, it has signed a flurry of bilateral agreements with Beijing, covering everything from free trade to infrastructure development.

“China is looking to use Panama as a transportation and logistics hub given Panama’s strategic location, stable political environment and open economy,” explains Ellie Vorhaben, economist at research firm IHS Markit. Indeed, China is the second-biggest user of the Panama Canal, behind the US. It is also the main supplier of the sprawling Colón Free Zone, Panama’s largest. Vorhaben adds that the Central American country is “hoping to work with China to develop Panama as a main point of entry for Chinese products and investment into Latin America”.

To this end, it has inked with China a US$5bn, 450km railway project agreement, financed by the Chinese, which will link Panama City to the border with Costa Rica – the country’s first rail network to be built outside of the Panama Canal zone.

Debt trap diplomacy

For some, however, this megaproject is reminiscent of others around the world which serve as cautionary tales of how China’s largesse can amount to a debt trap for vulnerable countries. A columnist writing for the country’s main daily newspaper, La Estrella de Panamá, recently referred to the project as a train loaded with “cuentos chinos” – a particularly apt Spanish expression which translates literally to “Chinese stories”, and means “tall tales”. Making reference to Sri Lanka’s Hambantota Port, which the South Asian nation eventually had to hand over to China after finding itself unable to pay its debts, and Kenya’s Mombasa Port, which may be repossessed by the Chinese after Kenya failed to repay a US$2.2bn loan for the construction of a railway track from Mombasa to Nairobi, the columnist, a retired US army corps engineer, warned of the potential repercussions to Panama of infrastructure projects paid for with Chinese money.

“There are differing views as to whether the Belt and Road is to the benefit of the world and its population or is actually some sort of nefarious route by which the Chinese are exerting influence not necessarily for the benefit of all,” Peter Hirst, partner at Clyde & Co and ambassador to the commission of the ICC international court of arbitration on the BRI, tells GTR. In his view, it is the former. “The Belt and Road is genuinely a means by which the Chinese are generating wealth.”

While he concedes that the Hambantota Port has been an embarrassment for the Sri Lankan government, he challenges that the country as a whole has done well out of the project. “Land values in Sri Lanka have increased enormously, and the people who benefited from that are the Sri Lankans. There is an enormous amount of manufacturing taking place around Hambantota that previously wasn’t,” he says.

Vorhaben, too, sees little harm to Panama from its blossoming relationship with China – as long as it gets its house in order. “If Panama can take the right legislative and fiscal steps, this influx of Chinese investment could allow it to better position itself as a key player in world trade,” she says. “While Panama is likely able to absorb future increases in public debt without putting pressure on its credit rating, its debt burden is still moderate, and there is a need to develop macroeconomic policies to strengthen the country’s ability to deal with external shocks. Repayment capacity is a bit limited by the country’s external debt burden; however, the completion of the canal extension projects will open up additional resources.”

New markets for Panama

For their part, Panama’s exporters are thrilled about the BRI and the possibilities of breaking into the vast Chinese consumer market. Following the signing of a phytosanitary protocol agreement in December, Simply Natural Harvest, which currently exports fruits from mangoes to avocadoes through the Panama Export programme to Germany, France, the Netherlands and Norway, inked a deal at the China International Import Expo 2018 with one of China’s largest fruit importers, which it says will open the way for the export of its products to China. While Panama can’t compete with Thailand and the Philippines in terms of proximity to the Chinese market, the Panama Exporters Association believes its growers can fill an important niche for high-quality, premium fruit.

With its enviable geographical location and its canal, Panama is an obvious gateway into Latin America for the BRI. A further 14 other Latin American countries have also signed on to the expanded initiative, mostly smaller Central American and Caribbean nations, and comparatively less open economies such as Venezuela and Bolivia. Despite growing Chinese involvement in their economies and trade balances, regional heavyweights Argentina, Brazil, Colombia and Mexico are yet to join the BRI party. One major coup for the BRI, however, has been the accession of Chile, which Clyde & Co posits is the second natural gateway in the region for the initiative.

“Chile and Panama offer China two important physical entry points into the region. Chile, in addition, features an attractive legal framework for the protection of Chinese investments in the country,” the law firm says in a note.

“What the Chinese have sought to do now is to cement their plan in two hubs,” explains Clyde & Co’s Hirst, who co-authored the note. “They’ve chosen Santiago and Panama. Panama is an obvious choice due to its location, but so is Santiago, and it’s also resource-rich and an easy place to do business.”

Chile: an old friend for China

Chile has long been a friend of China, being the first Latin American country to sign a free trade agreement with it in 2005. Indeed, the first sight a visitor sees upon leaving Santiago’s Arturo Merino Benítez International Airport is the Chinese Development Bank building. “Chile and China already have an established trade relationship, and Chile’s limited sovereign risk, fiscal health and stable politics put it in a good position to utilise the BRI to grow its economy, for example, through the expansion of the lithium sector,” says IHS’s Vorhaben, who believes that given sufficient investment, Chile could significantly expand its export levels of the strategic mineral. “If Chile can successfully work with Chinese investment in the lithium sector, not only would it expand the export of lithium, it could also diversify its export base by exporting developed lithium goods, as opposed to primary goods.”

Sebastián Piñera, Chile’s pro-market president, is keen for his country to benefit to the maximum extent from the BRI. On the table for Chinese investment include a US$1bn undersea fibre-optic cable megaproject which would connect Latin America and the Asia Pacific region. Talks on this were already underway in 2015, but there are hopes for the project to gain steam now it has been folded into the BRI agreement. Piñera has also spoken publicly about his admiration of China’s environmentally-friendly electric vehicles and buses, which many see as an invitation for the Chinese to modernise Chile’s creaking urban transit networks. Unlike its smaller neighbours, Chile has little to fear from taking on Chinese debt.

“Financing requirements for the initiative are large enough to expand debt levels to unsustainable levels. However, Chile’s ample foreign reserves and light external debt mean that it has ample repayment capacity for whatever debt it takes on. In addition to Chile’s limited sovereign risk, Chile’s stable politics also present limited risk. The country has strong institutions, good relations with foreign creditors and multilateral agencies, and clear legislative framework for investment which favours private investment and fights against corruption,” says Vorhaben.

Around the world in countless Chinese trade routes

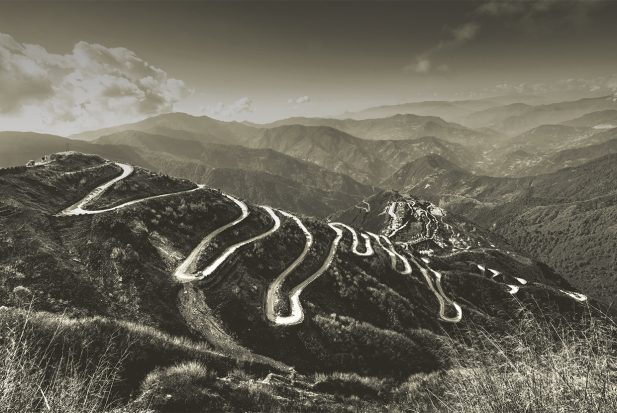

With the BRI’s integration into Latin America well underway, China’s dominance of global trade and investment has taken another great leap forward. The next step, the so-called Polar Silk Road, will see China, Russia and existing BRI partners create a new marine economic route through the Arctic Ocean. “Imagine the globe,” says Clyde & Co’s Hirst. “There is the belt going across the land from China to Europe. There is the road connecting Africa, around Sri Lanka, to China, all the way around up the west coast of South America and across the Panama Canal, and then you go up through Europe and then, with the Polar Silk Road, you go over the top of Russia again. They have got the whole globe covered, apart from one bit: the top of Alaska. We know for a fact that there are plans afoot for that to happen, and that then increases Latin America’s opportunity to reach new markets. People are rather excited about this prospect. The people who are less excited are the Americans, and we think this partly accounts for some of the recent trade war issues.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the US is horrified by China’s latest overtures in what it once considered its backyard. At last year’s Apec summit and in recent meetings with leaders of Central American states, US vice-president Mike Pence took pains to warn of debt traps, and in one particularly unsubtle jab at the Chinese, urged countries to avoid “a constricting belt” or a “one-way road” in their commercial partnerships.

Whether the region is a pawn in a larger geopolitical game of chess for China as it seeks to cement its dominance over the US is up for debate. For now, though, Latin America as a whole, and Chile and Panama in particular, seem content with their lot as the BRI arrives on their doorstep, bringing with it promises of riches.