Despite a tough year, Mexico remains one of the most promising economies in Latin America. Melodie Michel travels to Mexico City to find out why.

As this magazine went to press, the Mexican peso was dangerously close to the 20-to-the-dollar mark, causing concern in the business community. The country’s current account deficit was the largest since 1999 and rating agencies had cut growth forecasts from around 2.4% to 2% for 2016. Most worryingly, there were rumours that a credit rating downgrade was on the cards if things didn’t improve.

Yet at GTR’s Mexico Trade and Export Finance Conference at the end of October, the mood was optimistic. “Latin America is adjusting to a new reality. The US is not growing as much, and US production is suffering a recession. For Latin America, especially countries like Brazil, the adjustment has been quite sudden. Mexico, on the other hand, has been adjusting in a more orderly way. Amongst bad news, this should be considered a good thing,” said Carlos Capistran, chief Mexico economist at Bank of America Merrill Lynch (BofAML).

To understand the reason why investors are not panicking about Mexico’s apparent troubles, we need to look at the root of these issues.

For example, the devaluation of the Mexican peso had a lot to do with the presidential election campaign in the US. In fact, at the time of writing, it had become an indicator of the likelihood of a Donald Trump presidency: when Trump did well in polls or at debates, the peso went down; when he lost popularity, it recovered. On the back of the final presidential debate on October 10, the peso reached a peak of 18.455 against the US dollar.

A Trump presidency would be terrible news for the Mexican economy, but as the election result should be announced before many of you read this, and because Hillary Clinton enjoyed a double-digit lead in the polls at the time of writing, things should be looking up for the currency.

Speaking to GTR on the sidelines of the Mexico event, HSBC’s Mexico product head of global trade and receivables finance, Luis Fernando Mendoza, said: “The clients have been a lot more aware and concerned about our exchange rates, so they come to us a lot asking for support and advice. We’ve been very careful on reviewing how the clients do business in terms of which currency they use to sell and to collect – that’s something that wasn’t so critical a few years ago.

“We expect to see some volatility, but after the US election there won’t be as much uncertainty as in the last year. We’re now in a good position to start thinking ahead and start regaining momentum in world trade.”

Another issue is the current account deficit, which, according to Arnulfo Rodriguez, senior economist at BBVA Bancomer, has been made worse by the low oil prices of the last two years. “Foreign direct investment (FDI) in oil could finance about 50% of the current account deficit,” he said at the conference, and looking at recent news, this forecast may well come true.

The Mexican government is due to auction 10 deepwater drilling areas on December 5, hoping to raise US$44bn in its first-ever attempt to open the market to international oil companies.

“Of course, the energy reform [enacted in 2013] was affected by the oil price and the reaction of foreign investors was to put on hold many of their investments. However, Mexico has very important deepwater reserves that are going to be important in the future,” Mauricio Munguia, head of the Latin America desk at Santander UK, tells GTR.

In August, Exxon Mobil, Chevron and Hess agreed to bid together for this auction, against no fewer than 18 other oil majors including Shell, BP, Total and Mexico’s own Pemex.

“The appetite for the reserves is there and this bid proves that foreign companies want to participate,” Munguia adds.

Moreover, oil prices are expected to recover in the coming months and years – BofAML’s Capistran placed it at US$61 per barrel in 2017 – which will also be very helpful to Mexico.

And as shale takes a more important spot on the global oil stage (see page 74), Mexico is expected to capitalise on its northern reserves, thought to be extensions of the Eagle Ford basin in South Texas. Mexico’s energy secretary Pedro Joaquín Coldwell said in a speech in September that the government could begin shale auctions any time after March 2017, creating another source of FDI for the country.

The state of the oil sector is not the only thing affecting the current account deficit: the country is also attempting to strengthen its public finances. The 2017 budget was announced by finance minister José Antonio Meade – who was appointed when his predecessor, Luis Videgaray, resigned in protest against President Peña Nieto’s soft handling of Donald Trump’s visit in September – at the start of October. It includes cuts of almost Ps240bn (US$12.9bn), adding to the Ps169bn expected to be cut in 2016, and Ps124bn saved in 2015.

According to Meade, the cuts will include scaling back Pemex’s output to a 36-year low of 1.925 million barrels a day, as well as slashing the number of government personnel and reducing government operating costs by about a fifth.

Manufacturing strength

Mexico’s economic promise is best seen in foreign investors’ faith in its manufacturing sector. Despite continued drops in exports since the start of 2016 (up to 10% year on year in July), investment in the automobile industry has made countless headlines.

In September, Audi inaugurated a high-tech US$1.3bn Q5 crossover factory in San José Chiapa, with a production capacity of 150,000 cars a year. BMW is investing US$1bn into a new plant in San Luis Potosi, which will have a similar capacity. Mercedes-Benz is expected to set up shop in Aguascalientes with a US$1.4bn investment.

Ford caused controversy (and fuelled the Trump campaign) in September by announcing that it would move all its small car production to Mexico within the next two to three years – though it quickly added that the move would not mean job cuts in the US.

Foreign automakers have invested at least US$13.3bn in Mexico since 2010, more than half of which has come from outside North America, according to the Centre for Automotive Research.

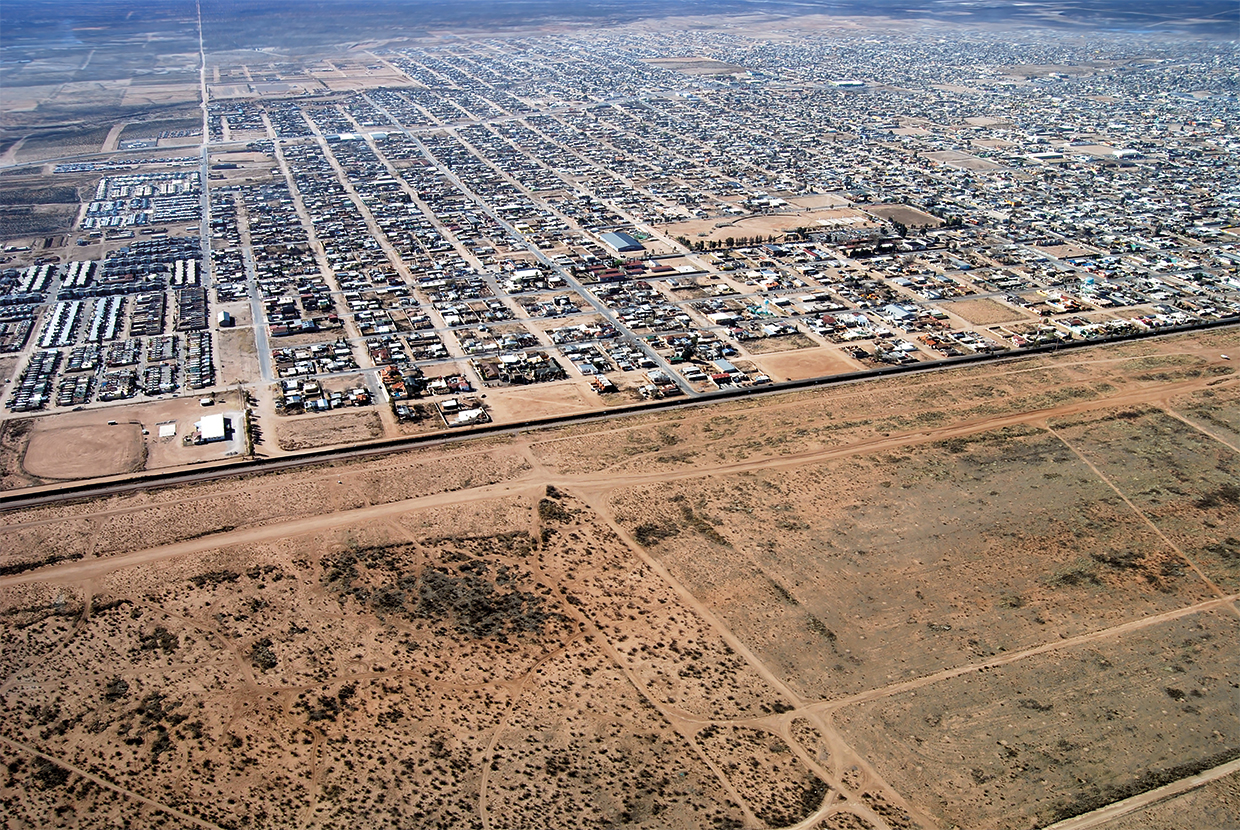

In an on-stage interview with GTR at the Mexico conference, Luis Enrique Zavala, vice-president of the National Association of Importers and Exporters of the Mexican Republic (ANIERM), cited a young workforce, 3,000km of border with one of the largest world consumer and free trade agreements (FTAs) as reasons for this appeal.

Indeed, at a time when FTAs are at the centre of widespread criticism, some are making the argument that it is Mexico’s multiplicity of agreements that makes it such an attractive manufacturing destination.

In an October 19 CNBC interview, Bernard Swiecki, director of the automotive communities partnership at the Centre for Automotive Research, said: “That’s what gets lost in the narrative. FTAs are driving BMW and Audi, but they’re not FTAs with us [the US].’’

Of course, labour costs are playing an important role in Mexico’s appeal: the average Mexican autoworker earns the equivalent of US$8 to US$10 an hour. According to the Centre for Automotive Research, average labour costs in the Detroit Three (General Motors, Ford and Fiat Chrysler Automobiles) range between US$48 and US$58 an hour. But salaries rise, and the recent trend towards “re-shoring” from countries like China back to a company’s home country is evidence that low-cost labour alone is not enough to invest in a country in the long term.

What Mexico has that others don’t is – once again – its proximity to the US, and more particularly, its research and development (R&D) capacities.

Chris Camacho, the president of the Greater Phoenix Economic Council (GPEC), speaks to GTR about the recent joint efforts of his organisation, the City of Phoenix and Pro-Mexico (the country’s tourism and investment promotion vehicle) to encourage companies to set up shop in the Arizona-Sonoma region.

“Arizona has a very strong competency in R&D and engineering, and obviously the manufacturing sector both in Arizona and Mexico are very strong, mostly around electronics, airspace and defence. We’re jointly targeting US companies that have gone abroad for cost optimisation reasons and showing them the value proposition for them to re-shore with that dual approach of Mexico and Arizona,” he explains.

He says rising worldwide transportation costs and increasing labour costs in developing countries have contributed to the renewed appeal of the region for manufacturers. In fact, the organisations expect to announce the first re-shoring success story before the end of 2016.

“What I foresee is that you’re going to see continued opportunities in Sonoma in particular to create one of the world’s most impactful mega-regions. This unique relationship will continue to develop. We’re seeing companies that want to do R&D in the auto sector in the US and look for manufacturing opportunities in Mexico where they can lower their operating costs. That’s a good partnership going forward,” Camacho adds.

Mexico has also been doing a lot to diversify export markets – a smart move, judging by the impact of the US election’s campaign promises on the country’s economy.

“When you share a border with one of the largest economies in the world, there are benefits. However, Mexico has been very active in finding new trade partners. It has been diversifying in terms of sectors, so as we move to different sectors we are also developing new trade blocs such as the Pacific Alliance [a bloc including Mexico, Chile, Colombia and Peru],” Munguia says.

Banking sector

Because of its economic diversity and resilience, particularly compared to more commodity-led and China-dependent Latin American countries such as Brazil and Chile, Mexico has continued to attract banking investment at a time when most global banks have exited much of the region.

Between 2006 and 2015 Citi sold 26 of its 50 foreign consumer banking units, including Brazil, Argentina and Colombia, yet it just announced a US$1bn investment in its Mexico subsidiary, recently rebranded CitiBanamex. Acquired in 2001, the bank holds a 16% share of total deposits in the country and contributes about 10% of Citi’s revenues, more than any other of its foreign retail franchises.

HSBC has followed a similar path: having exited most of Latin America (most recently selling its Brazil subsidiary to Bradesco), the bank recently announced a US$290mn investment in its Mexican subsidiary, signalling that it intends to remain in the market.

Though it’s impossible to predict just how bad a Trump presidency would be for the Mexican economy, a stress test conducted in October to evaluate the banking sector’s ability to weather such an event showed positive results. “These exercises showed that the banking sector maintains adequate levels of capital and liquidity to face adverse scenarios,” concluded the Financial System Stability Board (CESF), which includes representatives from the finance ministry, the Bank of Mexico and the banking regulator CNBV.

Mexico managed to stay the course of growth and stability in the midst of heightened political risk and regional recession, and now that a recovery is expected in both, it is poised to reap the benefits of its successful strategy.