Lex Greensill and Sanjeev Gupta were once such close business associates that they owned matching private jets. Now, with both facing fraud investigations, the duo are making conflicting claims about each other’s conduct. John Basquill examines the latest details on the future receivables, circular trades and questionable invoices lurking behind a major financial scandal.

In the few years leading up to the collapse of Greensill Capital, the lender’s founder and chief executive Lex Greensill had built a remarkably close working relationship with metals tycoon Sanjeev Gupta.

In 2016, after posting losses of US$54mn – a steep increase from the previous year – Greensill was looking for ways to galvanise its business, which was ostensibly built around supply chain finance (SCF) and lending against trade receivables.

Around the same time, Gupta was looking for financing. Multiple sources have told GTR that around that period, Gupta’s trading house Liberty Commodities and parent company Liberty House Group had become ostracised by much of the traditional banking sector.

The duo struck up a close working relationship, and the following year, Greensill’s revenues soared and the company returned a profit. It later emerged that nearly three quarters of its net revenue that year was from Gupta-related companies.

Greensill and Gupta became inextricably tied, locked in what former Greensill advisor and UK Prime Minister David Cameron later described as a “symbiotic relationship that obviously went wrong”.

Their business relationship was no secret. At the height of their companies’ growth, Greensill and Gupta owned matching private jets, with vanity tail signs marked with “M-GFGC” and “M-ETAL” respectively.

Over time, however, Greensill’s exposure to GFG Alliance – a loose network of companies owned by or linked to Gupta – became a growing source of concern.

In mid-December, just months before Greensill Capital’s collapse, German authority BaFin urged Bremen-based Greensill Bank to reduce its exposure to a single customer – a request which Lex Greensill said “was going to be impossible for us to comply with”.

That exposure also meant that when Greensill collapsed, the GFG Alliance lost what Gupta describes as the group’s “most significant financial backer”. Though refinancing deals have been struck with some lenders, including commodities giants Glencore and Trafigura, as well as US asset manager White Oak, as of press time many GFG companies are still seeking refinancing.

“With hindsight, GFG’s concentration on one financial provider risked instability,” Gupta admits in written evidence to the UK parliament’s Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) Committee, made public in July.

“It is not something GFG would repeat, and it now has a policy of seeking, wherever possible, to diversify its capital base as it goes through the current period of refinancing.”

Suspicions over GFG invoices

One of the challenges facing the GFG Alliance in its bid to replace Greensill is a fear within the banking sector that GFG companies may be borrowing against suspicious invoices.

In the case of Greensill, suspicions emerged publicly after Grant Thornton was appointed as administrator, responsible for overseeing the company’s insolvency. The Financial Times revealed in early April that Grant Thornton had been unable to verify the authenticity of invoices that were used to raise financing from Greensill.

Citing correspondence and sources familiar with the matter, the newspaper said Grant Thornton approached several companies with outstanding invoices from Liberty Commodities – only to be told by those companies that no trading relationship had ever existed between them.

The UK’s Serious Fraud Office has since announced it is investigating “suspected fraud, fraudulent trading and money laundering in relation to the financing and conduct of the business of companies within the [GFG] Alliance, including its financing arrangements with Greensill Capital”, though the full scope of its investigation is not public.

Gupta responded by saying he had not seen the specific invoices in question, but claimed the Financial Times’ findings are likely reflective of future receivables programmes provided by Greensill, rather than real invoices.

“Many of Greensill’s financing arrangements with its clients, including with some of the companies in the GFG Alliance, were prospective receivables programmes, sometimes described as future receivables,” his written evidence claims.

“As part of those programmes, Greensill employees identified companies with whom its counterparties could potentially do business in the future. Greensill then determined, at its discretion and based on insurance capacity it had, the amount of each prospective receivables purchase and its maturity.”

Similar claims were made by Bluestone Resources, a US mining company that filed a fraud lawsuit against Greensill shortly after its collapse.

As described by Gupta, that practice is seen by one trade finance industry insider as a “rogue outlier case” compared to the wider provision of SCF.

“If you try and dress up a future receivables deal as a supply chain finance transaction then basic questions will be asked and that simply won’t get past a bank’s risk committees, if it gets there at all,” another source says.

As a financing mechanism, future receivables are not unheard of. But Sean Edwards, chair of the International Trade and Forfaiting Association (ITFA), says they would generally make up only a “conservative subset of a receivables facility, maybe 5% or something like that”.

They would also likely be based on historical data, and would therefore relate to existing clients only – not customers with whom there is no current or earlier relationship. Vitally, Edwards adds, the programmes would generally have to be accounted for as unsecured debt.

Future receivables and competing claims

The case has become more complex, however, with Lex Greensill repeatedly denying Gupta’s characterisation of the future receivables programmes offered by the lender.

In May, he told a UK Treasury Committee inquiry that Greensill had never knowingly provided financing against invoices where there was no pre-existing customer relationship.

“A condition of our facilities… is that they must do business with the customer. They must have a history to support that, and the data to support that,” he said at the time. That data would then be used “to see what was going to happen in the future and allow businesses to be able to access credit”.

He reiterated that assertion in a statement to Australia’s ABC News, whose investigative programme Four Corners broadcast a feature on Greensill’s fall in July 2021.

There are some question marks over Gupta’s claims. Cynthia O’Murchú, an investigative journalist at the Financial Times, told the BEIS Committee inquiry that the invoices unearthed by Grant Thornton do not appear to relate to future or hypothetical trading activity.

Invoices include precise dollar amounts of individual trades, rather than rounded estimates, as well as details of specific warehouses that goods would be shipped to, O’Murchú explained – features more typical of real trades than forecast activity.

Crucially, she added, those invoices are also dated in the past. Javed Siddiqui, professor of accounting at the University of Manchester, told the inquiry that investigators should therefore examine “whether that is showing their accounts, because we are talking about audited accounts”.

“If these are backdated, these are accounts receivables rather than future receivables, and there has to be corresponding revenue recorded somewhere,” he said.

Another issue is that documentation published by Credit Suisse – the largest investor in Greensill-arranged SCF programmes at the time of its collapse – shows Liberty Commodities did not have its own future receivables financing line, though other GFG companies did.

O’Murchú added that if Greensill had identified prospective buyers of Liberty and arranged future receivables, as stated by Gupta, that would suggest “someone at Greensill sat down and started manufacturing invoices, which does not make sense in the way that they are presented”.

But even if Greensill’s future receivables offering was restricted to existing customer relationships, details of those programmes still raise questions.

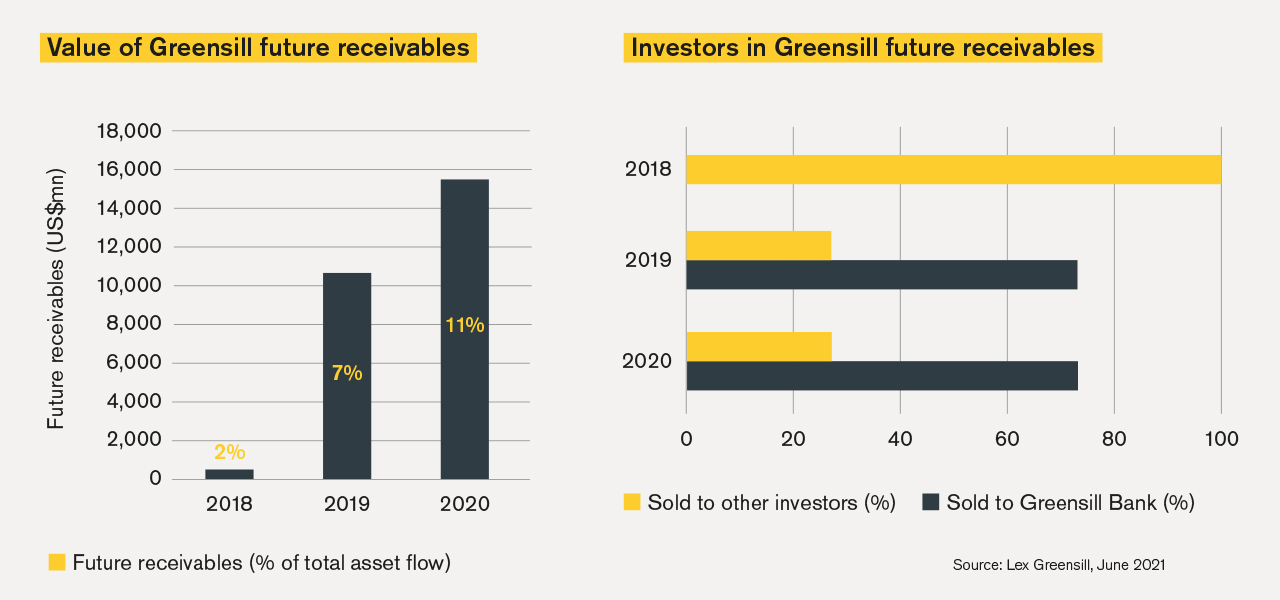

According to written evidence from Lex Greensill published by a Treasury Committee inquiry in late June, the lender rapidly scaled up its use of those programmes after 2018. Greensill’s future receivables lines were valued at US$470mn in 2018, but soared to US$10.6bn the following year and US$15.4bn in 2020 (see graph).

The same disclosure states that as a proportion of Greensill’s total asset flow, future receivables accounted for 11% in 2020, up from 2% two years previously.

The later figure is far in excess of the 5% suggested by ITFA’s Edwards as a conservative subset of wider receivables financing.

Greensill future receivables were also sold exclusively to outside investors in 2018, but in 2019 and 2020, 73% were sold to Greensill Bank in Germany – equivalent to US$7.5bn and US$11.2bn in value (see graph).

That change in strategy is not explained, and Greensill Bank has not proven a safe haven for investors. After regulators ordered a moratorium on the bank in March, many depositors – including German municipalities attracted by strong interest rates – lost funds that were not fully covered by a federal deposit insurance scheme.

Further, the committee had requested that Lex Greensill distinguish between lending “linked to an invoice already issued” and lending where “there was no expected invoice, or there is an expectation which is not based on repeated cashflows”. He did not do so in his written evidence.

Circular trades and hidden names

Meanwhile, the pressure on Gupta’s GFG Alliance goes beyond future receivables. Liberty and other GFG-related companies have long faced scrutiny for raising financing from trade transactions involving other companies linked to Gupta.

S. Alex Yang, associate professor of management science and operations at the London Business School, told the BEIS Committee hearing that in his view, this structure “is a type of circular financing”.

“By doing this, I could artificially increase my accounts receivable and accounts payable at the same time,” he said. “A basic principle of supply chain finance is that I look at the amounts of accounts receivable and accounts payable and that allows me to determine what amount to lend to you.”

Increasing leverage by inflating those accounts would be considered “very suspicious” by a company with sound risk management practices, Yang said.

But Gupta has defended the use of circular trading structures – or repo deals, where goods are sold to a related party then repurchased as a means of raising financing against the relevant invoices – as a common structure in commodities trading.

“It is especially popular as it is a more secure form of financing compared to other unsecured loans or overdrafts,” his written evidence says. “This is the main business of many traders around the world and many plants rely on such funding mechanisms to augment their working capital.”

However, the role of Gupta companies in metals trading has a murkier history. GTR revealed in July 2021 that Westford Trade Services, a lender that later drew financing from Greensill-arranged funds, had historically attempted to hide the involvement of Liberty in its trading activity.

Hong Kong-headquartered Westford, now registered as Westford Limited, is a commodity trading house that has its roots in the steel trading industry. It has also acted as a non-bank financier, supporting companies associated with the GFG Alliance.

Red flags had been raised about Westford’s relationship with the Liberty trading group as far back as 2015, according to an external due diligence report commissioned on behalf of an insurance company and seen by GTR.

That report includes correspondence suggesting Westford employees deliberately concealed the involvement of Gupta-owned Liberty in certain transactions.

In one example, presented as a metals trade brokered by Liberty in 2014, Westford’s chief executive requests that accompanying documentation makes “no mention anywhere of liberty please…not as sender not as dhl account etc [sic]”.

The transaction involved the sale of iron to Simec, also part of Gupta’s GFG Alliance.

In another example, an email seen by the report’s authors in 2016 but not reproduced in the report suggests that an unpaid invoice for US$2.5mn issued by Liberty was hidden by Westford staff from another company director.

According to the report, an email cited that director’s “blood pressure” as the reason for concealing the invoice. Former Westford employees told the authors that was “a regular practice with regards to Liberty”.

Statements generated by Westford’s accounts department would also avoid mentioning Liberty as a customer with outstanding debts, it adds.

Other red flags cited in the report include Westford continuing to do business with two companies in 2015 despite earlier employee suspicions over forged documents and fake trades. Those two companies are not presented as linked to GFG.

Representatives from Westford Limited could not be reached by GTR. Multiple calls to offices in London, Dubai and New York went unanswered, and two senior executives did not respond when contacted by email.

Sources familiar with the matter say Westford is widely understood to have provided financing for Liberty’s activities at the time covered by the report.

In an article published in April this year, Argus says Westford financed nickel trades between Liberty Commodities and steel producer Uttam Galva – whose founder was revealed by the Panama Papers to have ties to Liberty Commodities – that the publication says “make no sense in the context of Uttam Galva’s business”.

Argus has also revealed that Gupta’s Wyelands Bank financed uninsured receivables from Westford Trade Services.

The specialist metals publication says it has seen emails showing that Liberty Commodities’ chief executive Paul Francis arranged trades with Westford that were “seemingly independent of Liberty”.

Despite that, receivables worth US$19.8mn from Westford Limited were packaged and sold through a Credit Suisse supply chain finance fund, managed by Greensill, an audited annual report from 2019 shows.

Westford is also listed as an obligor in portfolio details published in April this year.

Greensill-originated SCF funds

The red flags over Westford Trade Services raise further questions over the integrity of the companies included by Greensill-arranged supply chain finance funds.

Greensill used three Luxembourg-based special purpose vehicles – Lagoon Park Capital, Wickham and Hoffman – to securitise receivables, which would then be sold to investors via Credit Suisse.

According to a 2019 audited report published by Credit Suisse, other companies whose receivables were securitised and sold included Agritrade and Phoenix Commodities, two traders that have since collapsed amid allegations of fraud.

Court documents seen by GTR show that Greensill entered into a financing agreement with Agritrade’s Ng Xinwei in October 2018. After the company collapsed in March 2020, bank creditors accused it of forging documents in order to secure financing multiple times on the same trades.

Phoenix, meanwhile, engaged in trades arranged by Liberty Commodities and also drew funding from Gupta-owned Wyelands Bank, according to documents seen by Argus.

Receivables from Gulf Petrochem, now known as GP Global, were also included in the Credit Suisse funds. The company is currently undergoing restructuring, with evidence emerging of allegedly irregular or fictitious trades.

GTR revealed in February 2021 that GP Global was left with “significant bad debt as the trade receivables due from these ‘trades’ are unlikely to be recoverable”, according to court documents filed by the company’s chief restructuring officer.

The total value of assets from those four companies, in the 2019 accounts, was over US$87mn. Receivables from Liberty Commodities totalled a further US$136mn.

Receivables from numerous other companies bearing the Liberty name were also securitised by Lagoon Park Capital and Wickham, accounts for the two SPVs show. Hoffman does not itemise the companies whose receivables are securitised.

Greensill declined to comment when contacted by GTR. Sources familiar with the funds argue that the responsibility for supplying legitimate invoices ultimately lies with the trading companies themselves, and that Greensill was not obliged to check whether invoices were legitimate.