The Middle East and North Africa (Mena) has long been a powerhouse in global trade, largely driven by its vast oil and gas reserves. But with Cop28 on the horizon, the region has an opportunity to chart a new path towards sustainable growth – although risks abound. Eleanor Wragg reports.

After bucking the decline in global economic growth last year, the Mena region is now experiencing a deceleration, according to the latest World Bank figures.

In its April economic update, the multilateral body now expects the region’s economies to grow by just 3% in 2023, down from 5.8% in 2022, as macroeconomic headwinds and commodity price volatility weigh on activity.

Oil exporters, which last year reaped the benefits of the price boom following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, are expected to experience the sharpest slowdown. After posting a 7.3% GDP expansion in 2022, the oil-producing Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries – Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) – are set to see GDP growth fall to 3.2% in 2023 as oil prices unwind from the highs of 2022.

Meanwhile, among oil importers, which were battered by higher food and energy bills in 2022, growth is projected to remain roughly steady at around 3.6%, although much of this is driven by expectations of increased competitiveness for Egypt following the recent depreciation of its currency.

With oil sector gains largely exhausted, the region’s focus on economic diversification will be the linchpin of future growth. As the UAE prepares to host Cop28, marking Mena’s second consecutive climate summit, the GCC governments’ net-zero transition pledges are taking on renewed importance. But shaking off a stubborn dependence on hydrocarbons is easier said than done, and the ability to bolster productive sectors outside of oil and gas will be a decisive factor in Mena’s economic outlook going forward.

Export outlook

In its most recent trade growth outlook, the World Trade Organization (WTO) says it now expects global merchandise trade volume growth of 1.7% in 2023, down from 2.7% in 2022, as the effects of the war in Ukraine combine with stubbornly high inflation, tighter monetary policy and financial market uncertainty to put the brakes on exports.

The Middle East, which last year posted a world-beating 9.9% growth in export volumes, is set to experience a dramatic reversal of fortunes this year, with WTO economists forecasting 2023 export volume growth of just 0.9% for the region. Meanwhile, after climbing by 9.4% last year, import growth will also slow, albeit to a lesser extent, to 5.5% this year.

In the first half of 2022, the economic consequences of the war between Russia and Ukraine and its associated sanctions prompted an oil price surge (see figure 1), which took a barrel of crude to a multi-year high in March. By the second half, a decline in global fuel demand caused by a combination of severe Covid-19 containment measures in China, a warmer-than-expected northern hemisphere winter and soaring inflation saw oil prices give up most of the year’s gains.

By the beginning of 2023, an expected price boost from the reversal of China’s zero-Covid policy and supply shortfalls from the December EU ban on Russian crude oil were offset by sluggish demand amid a gloomy global economic backdrop.

In March this year, fears about the health of the world’s banking sector following the collapse of two US lenders and the failure of Credit Suisse pushed crude to 15-month lows, leading the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) to lower its short-term Brent spot price outlook to US$82.95, down from US$83.63 previously.

However, this figure was soon revised upwards to US$85.01 following a surprise decision on April 3 by the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (Opec) to cut crude production by 1.2 million barrels per day, ostensibly to maintain price stability in the face of weak projected demand.

Nonetheless, this still represents a marked decline from 2022’s average price of US$100 a barrel, which will result in a year-on-year reduction in petrodollar inflows into Mena’s oil-exporting countries.

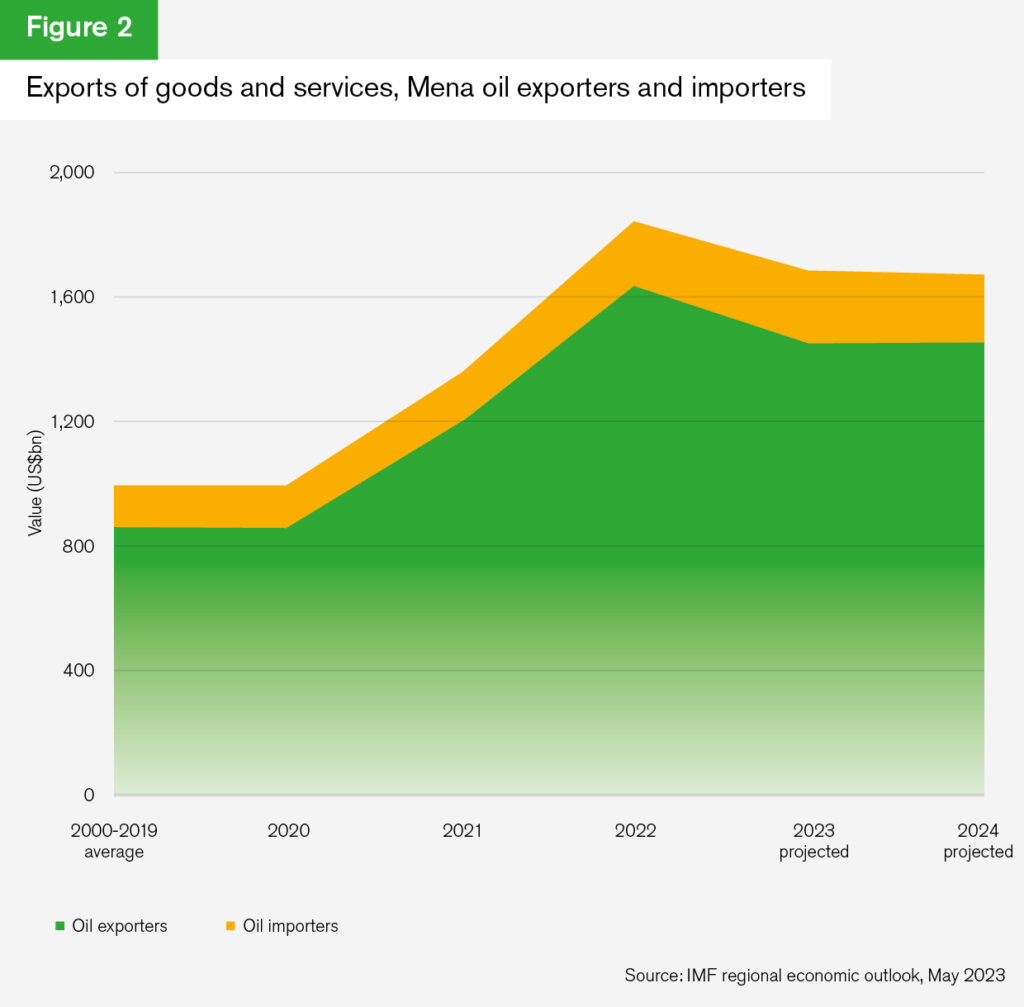

In value terms, according to the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) regional economic update, Mena exports will be US$1.66tn in 2023, down from US$1.84tn in 2022 – a decrease of almost 10%. (see figure 2). Mena’s oil exporters’ share of total exports will decline to 87% in 2023, from 89% last year.

Beyond the barrel: a sustainable shift away from oil

In recent years, oil exporters in the Gulf have sought to decouple their economic prospects from those of crude with initiatives targeted at boosting the non-oil sector. Launched during the second decade of this century, these strategies – among them Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030, the UAE’s Vision 2021, Qatar’s National Vision 2030 and Bahrain’s Economic Vision 2030 – lay out a roadmap for a shift from resource dependence to a knowledge-based economy, largely through massive infrastructure investments.

The continued reform momentum is changing the shape of the region’s economies, with the IMF predicting non-oil GDP among Mena’s oil exporters this year to expand at “a healthy clip” of about 3.7%, broadly unchanged from 2022.

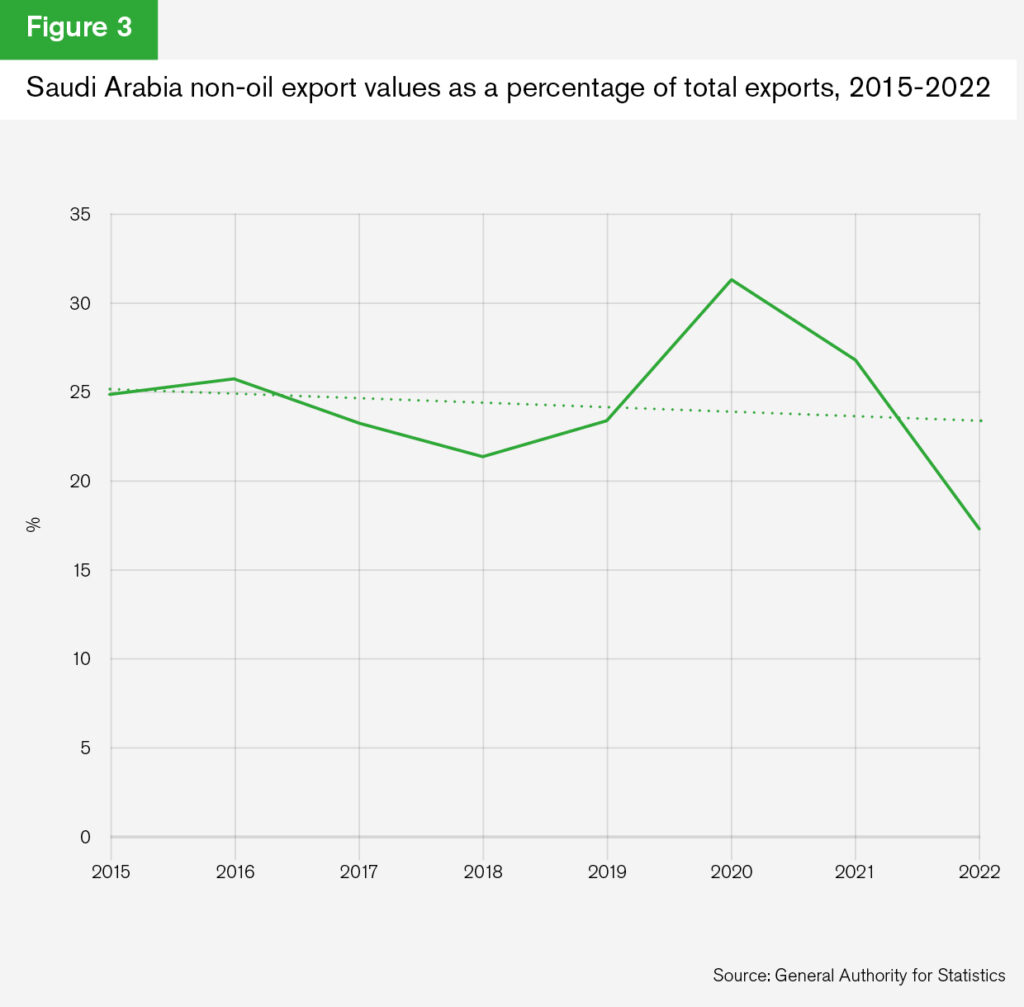

However, the make-up of exports in value terms remains relatively unchanged. Indeed, since the 2016 launch of its diversification strategy, non-oil exports as a share of total exports from Saudi Arabia, Mena’s largest oil exporter, have trended flat to lower (see figure 3).

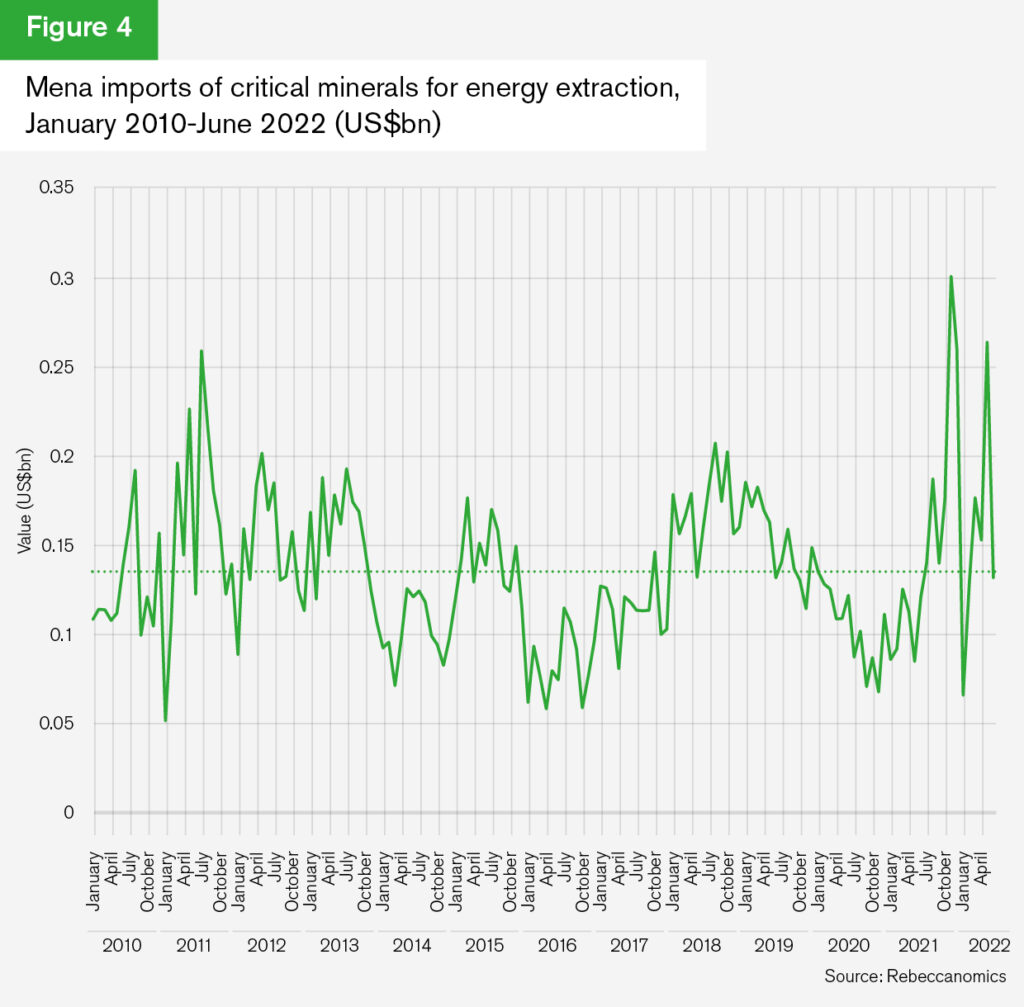

A look at the region’s imports tells a similar story. Imports of critical minerals for conventional energy extraction – the metals that are needed to support existing fossil fuel extraction activity – have also trended flat since the beginning of the last decade (figure 4).

“The core narrative is that nothing in reality has changed over the last 11.5 years in terms of the imports to support the region’s core business in mineral fuels,” Rebecca Harding, founder of trade economics consultancy Rebeccanomics, tells GTR.

According to energy major BP’s 2023 energy outlook, nothing is likely to change over the coming years, either. The report considers three scenarios – accelerated, net zero and new momentum – to consider a range of possible pathways for the global energy transition to 2050. In all three scenarios studied, the region’s shares of global oil and gas output increase.

However, what will change is the region’s use of its energy resources.

As their engagement with global climate change policy has deepened, the GCC states in particular have made major commitments to greenhouse gas reduction and the development of renewable energy.

As part of net-zero pledges, Saudi Arabia aims to meet half of its electricity demand through renewables by 2030, the UAE is targeting 44% by 2050, while Qatar plans to supply 20% of its electricity through solar energy by 2030.

Currently, according to figures from BP, nearly a third of oil and over two-thirds of natural gas produced in the Gulf is consumed domestically, largely as a result of burning hydrocarbons to generate subsidised electricity. The achievement of these pledges will mean more of the Gulf’s hydrocarbon resources will be destined for lucrative energy exports, while the region greens its own energy matrix.

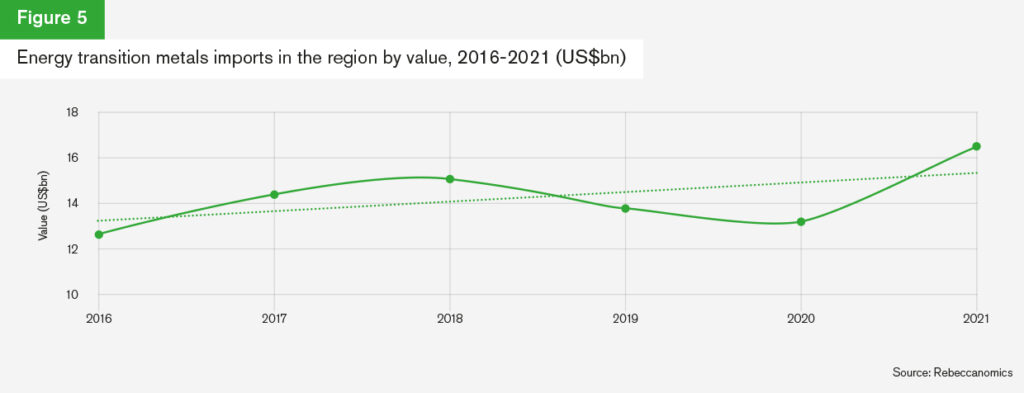

Import figures for energy transition metals demonstrate that a shift is already underway (figure 5), with an increase of 31% between 2016 and 2021, according to research by Rebeccanomics.

The region’s top exporters of energy transition metals are the UAE and Saudi Arabia, where imports have surged by 40% and 28% respectively over the same period. “While trade takes a long time to shift, this does show that the intent is there and that purchasing decisions are changing,” says Harding. “We might not be seeing very much in terms of export diversification, but import diversification towards the energy transition is underway and indicates a structural change.”

Sustainable finance gains in strength

This structural change is being accompanied by a rise in demand for finance to underpin it.

“Following Cop27 in Egypt and ahead of Cop28 in the UAE, the trajectory of the wider region’s green finance market has taken on new significance,” says Venty Mulani, data specialist, sustainable fixed income at Bloomberg LP in a note. According to Bloomberg data, last year saw green and sustainable bond and sukuk issuances in the GCC rise to a record US$8.5bn from 15 deals, compared with US$605mn from six deals in 2021.

This came amid a global decline for sales of new green and sustainable bonds, which fell by around 14% in 2022 due to growing economic uncertainty and rising interest rates.

“2022 proved to be a record year for green and sustainable bonds and sukuk in the Gulf, whereby the debut of several notable government-related entities and banks suggests sustainable finance is continuing to enter the mainstream in the region,” adds Mulani.

In the trade finance space, sustainability-linked activity is also increasing. In October last year, UAE-based First Abu Dhabi Bank announced the launch of sustainable supply chain solutions to support its clients’ transition to net zero through innovative finance solutions, while in December, Standard Chartered launched what it says is the first sustainable supply chain finance programme in the region, in partnership with Majid Al Futtain Retail, operator of the Carrefour franchise in the region.

“There is a huge shift around the sustainability agenda in the Middle East. The region is seeking to position itself at the centre of the energy transition, and this is showing up in trade finance trends,” says Harding. “As trade finance becomes more structured around ESG principles, corporates will have to become more compliant – albeit taking into account the reality of what the Middle East is, which is a fossil fuel producing region.”

Looking east for a greener future

As the Mena region’s focus on sustainability strengthens, so too is its relationship with Asia, according to research from Asia House, an independent think tank and advisory service.

“Cop28 will lead to increased focus on the Gulf states’ energy transition strategies, and our research has shown several synergies between the Gulf states and Asia on sustainability that are driving co-operation,” Freddie Neve, senior Middle East Associate at Asia House, tells GTR. He points to visits by Sultan Al-Jaber, the UAE’s Cop28 president, to Japan and China as indications of the country using its position as host nation to engage in diplomacy across Asia.

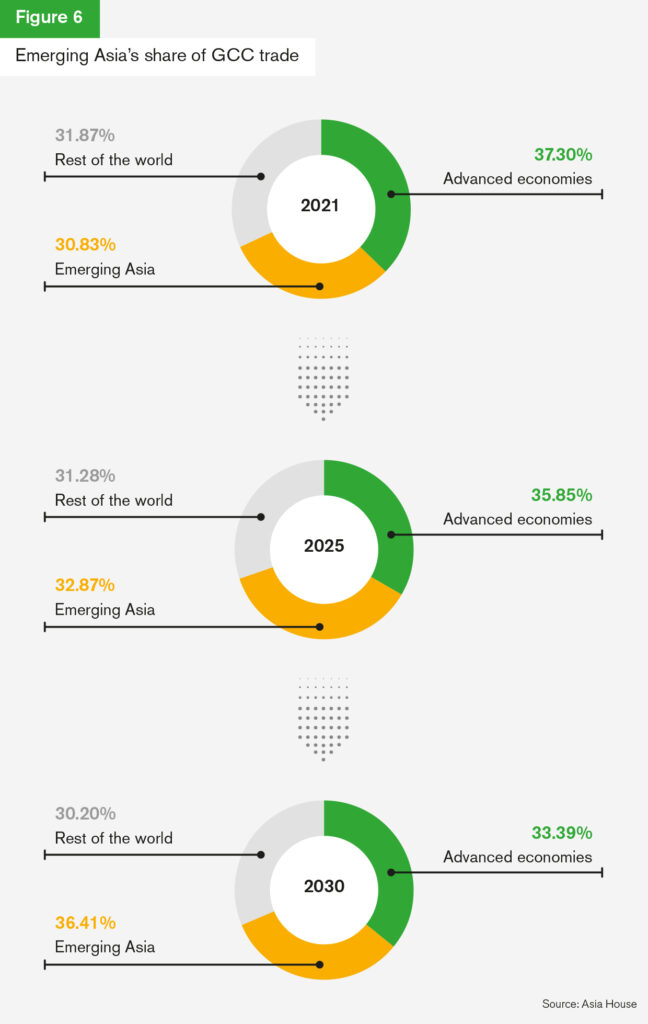

This tightening of ties is driving an increase in Asia’s share of GCC trade, according to figures collated by Asia House (figure 6), which finds that emerging Asia – a term it uses to cover the IMF’s ‘emerging and developing Asia’ list of 34 Asian economies, which includes China, India and the majority of Asean members, but excludes advanced Asian economies such as Japan, Singapore, South Korea, Hong Kong, Macao, Taiwan, Australia and New Zealand – will become the GCC’s largest trading partner by the end of this decade.

“The Gulf states, for example, want to become hubs for blue and green hydrogen production, whereas Asian countries – particularly Japan and South Korea – are interested in using hydrogen to assist their energy transitions. This has led to several MoUs signed between Asian and Gulf energy companies regarding hydrogen production,” says Neve, adding that Chinese firms’ growing involvement in solar projects throughout the Gulf are another strong indicator of increased co-operation between the two regions.

Transformation underway

While Mena will long continue to rely on oil for its trade fortunes, shifts are becoming apparent that indicate the region is repositioning itself for future growth.

“Simply looking at trade figures isn’t very helpful to understand the depth of what’s happening in the region, because the region’s trade is still dependent on fossil fuels,” says Harding. “But if you examine the rhetoric and look at the policies, it is clear that there is a shift in mindset. There is an emphasis now on sustainability, and the Middle East and North Africa is becoming a fulcrum for that sustainable activity.”

Nonetheless, tighter global economic conditions raise the potential of lower energy revenues, which could translate into less investment for green and sustainable projects, while an escalation of Russia’s war in Ukraine could revive commodity market volatility, fuelling additional inflationary pressures. As such, despite positive top-line indicators, Mena’s short-term trade outlook remains one with numerous downside risks.