The Suez Canal – a vital artery for global trade – was brought to a sudden standstill in March, when giant container ship Ever Given became wedged sideways across it. Though cleared after a week, experts warned that long-term disruption to trade activity could last months. John Basquill examines North Africa’s dependency on the canal, and the likely impact of its blockage on trade flows across the region.

When one of the world’s largest container ships became wedged across the Suez Canal on March 23, the impact on seaborne trade flows was immediate and drastic.

With the canal carrying around 12% of all maritime trade, German insurance and financial services company Allianz estimated that a single week of closure could cost the global trade industry between US$6bn and US$10bn.

Around 400 vessels were immediately impacted. Ships already in the canal were not permitted to turn round and head back out, while others queuing to enter faced a choice between waiting until the route was clear or undertaking the near two-week extended journey round the southern part of Africa.

Ever Given – the world’s 13th largest vessel by container capacity – was refloated on March 29, almost exactly a week after it had become stuck across a narrow section in the southern part of the canal. Its rescue was facilitated by a mammoth dredging operation, the deployment of two high-power seagoing tugboats, a 400m lever to free the front of a ship, and a timely high tide.

The ship was soon impounded by Egyptian authorities, however, and a legal tussle over who will bear the costs of the incident could mean the ship’s cargo and crew are stranded for months. As of press time it remains anchored in the Great Bitter Lake, which lies between narrower sections of the canal to the north and south.

The backlog of vessels was cleared relatively quickly, but details are now emerging of secondary effects from the hundreds of delayed shipments, including container shortages, high freight rates and disruption to supply chains that are expected to last several months.

Retailers affected include Swedish furniture giant Ikea, which had 110 containers on Ever Given and other delayed vessels, as well as electronics retailer Dixons Carphone. Delayed cargo has been reported across numerous sectors, including agri, livestock, fuel and machinery.

The bulk of commercial and media scrutiny of the disruption has centred on Asia trade flows with Europe and North America. Data from OceanInsights, an ocean freight intelligence platform owned by logistics visibility firm project44, shows that a staggering 78 vessels were delayed in reaching ports in Singapore, Malaysia, the North Sea and the US East Coast.

However, in North Africa, port call data – when combined with information on vessel delays, freight rates and container availability – provides evidence that the disruption to trade activity was not limited to those major ports in the US, Europe and Asia.

Impact on North Africa

World Bank data shows that Algeria, Egypt, Morocco and Tunisia all import significant quantities of goods from Asia, and China in particular, all of which would be expected to transit through the Suez Canal.

Algerian imports from China stood at US$8.3bn in 2017, the most recent year for which data is available, dwarfing shipments from France – its next largest import market at US$4.3bn. The majority of Chinese imports are made up of machinery, electronics, other manufactured goods and metals.

Algeria also imported goods worth a further US$1.7bn from Korea, generally in the same sectors, plus US$984mn from India.

Egypt’s two largest import markets also rely on the Suez Canal. In 2018, the country imported US$11.5bn worth of goods from China and US$5.7bn from Saudi Arabia, the latter mostly consisting of fuel. The same year, imports from Kuwait and India each totalled US$2.3bn, with substantial quantities also coming from the UAE, Indonesia and Iraq.

China is the third-highest source for Moroccan and Tunisian imports, again largely covering machinery and manufactured goods, as well as textiles and clothing.

In the other direction, exports from North Africa to Asia are lower – though Algeria exports a combined US$2.4bn to India, China and Korea, while Egypt exports US$2bn to the UAE, US$1.4bn to Saudi Arabia and over US$1bn to each of India and China.

Morocco also exports goods worth more than US$1bn a year to India, and in a March 2020 newsletter, the government’s Observatory of Logistics Competitiveness (OMLC) acknowledged the country has a “high dependence of some products on the Asian market”. The OMLC adds that in 2020, just 10 products accounted for 75% of Moroccan exports to Asia by value.

The Suez Canal therefore plays a vital role in North Africa’s trading activity, suggesting that the disruption caused by the blockage is not limited to European and American trade with Asia. Though data is scarce, signs are emerging that North Africa has felt the effects more than most.

OceanInsights reports that 13 vessels were delayed in reaching ports north of Suez, including eight at Port Said and three at Damietta, both in Egypt. A further six vessels were late to reach Tanger Med in Morocco, and one other ship reported late arrival at Misrata in Libya.

The total of 20 delayed vessels heading for North African ports is greater than the combined figure for all US ports, as well as for Malaysia, Iberia and the North Mediterranean. Only Northern Europe fares worse, when delayed arrivals at Rotterdam, Hamburg, Antwerp, Felixstowe and Southampton are combined.

Vessel behavioural data produced by maritime analytics firm Windward and shared with GTR also shows an impact on traffic and port calls in Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya and Egypt.

During the week of the blockage, the number of port calls by cargo ships and tankers spiked at 1,075 – potentially as carriers docked while deciding whether to turn back and re-route around southern Africa, or to wait until Ever Given was freed.

Similar figures were then reported for the following two weeks, yet towards the end of April and as of press time in May, activity levels have steadily declined, possibly indicative of a dip in seaborne activity as longer-term disruptive effects take hold. The number of port calls in the final week of April was 946, a drop of around 12%.

Long-term disruption: the domino effect

When the canal was cleared and traffic resumed, trade analysts at S&P Global-owned supply chain intelligence company Panjiva estimated it would take “at least 15 days of crossings above the ‘normal’ 50-60 vessels per day run rate to clear the current backlog”.

Beyond that, however, carriers were quick to warn that the effects could linger well beyond those initial few weeks.

Shipping and logistics giant Maersk issued a customer advisory on March 29 cautioning that “disruptions and backlogs in global shipping that could take weeks, possibly months, to unravel”. At the same time, Maersk’s digital logistics platform Twill added in a statement that the blockage “will have ripple effects on global supply chains for weeks to come”.

More recently, Twill has explained that each delayed journey “slows the arrival of containers at their destinations and delays when they can be emptied and then refilled with other goods towards their next destination”.

“Moving forward, port congestion is expected to be a significant hurdle as vessels will be arriving outside of their slotted appointment times and in large numbers as they all make their way through the canal in quick succession,” it warns.

Pawan Joshi, executive vice-president of product management and strategy at logistics software company E2open, says the disruption to supply chains can manifest in several different ways.

In some cases, finished goods are delayed in reaching the shelves and so force adjustments on the part of retailers and consumers. In others, components may be delayed en route to factories for processing and production – potentially meaning lines have to shut down and workers sent home.

“That initial impact, followed by reacting and starting the lines up again when the material arrives, is a much larger disruption,” Joshi tells GTR.

More complicated still is when components are sent to Asia for processing before being imported back to North Africa, Europe or the Americas for further work.

“A delay in processing in Asia causes delays in components moving back from Asia – and that domino effect starts multiplying pretty quickly. We’ve seen that across the board, and that is a much longer-term impact,” Joshi says.

Congestion, containers and freight rates

Concerns over port congestion and container availability were already rising before the canal blockage, having set in due to the transformative effect of the Covid-19 pandemic on worldwide seaborne trade.

Joshi explains that changes in consumer behaviour – triggered by people spending more time at home due to virus containment measures – led to an increase in demand for goods from Asia and helped spark a sustained 20% increase in ocean shipping volumes.

That shift meant the global trade sector was already in a weakened position when the canal blockage occurred, and so existing disruptions were exacerbated.

“We were already operating with a large demand-supply imbalance when it came to containers and vessels being in the wrong place,” Joshi says.

“Then, when you think about a week-long disruption to large vessels carrying large numbers of containers, that domino effect is even larger. Containers are in the wrong place, there aren’t enough vessels to pick them up, and ocean schedules are completely upside down.”

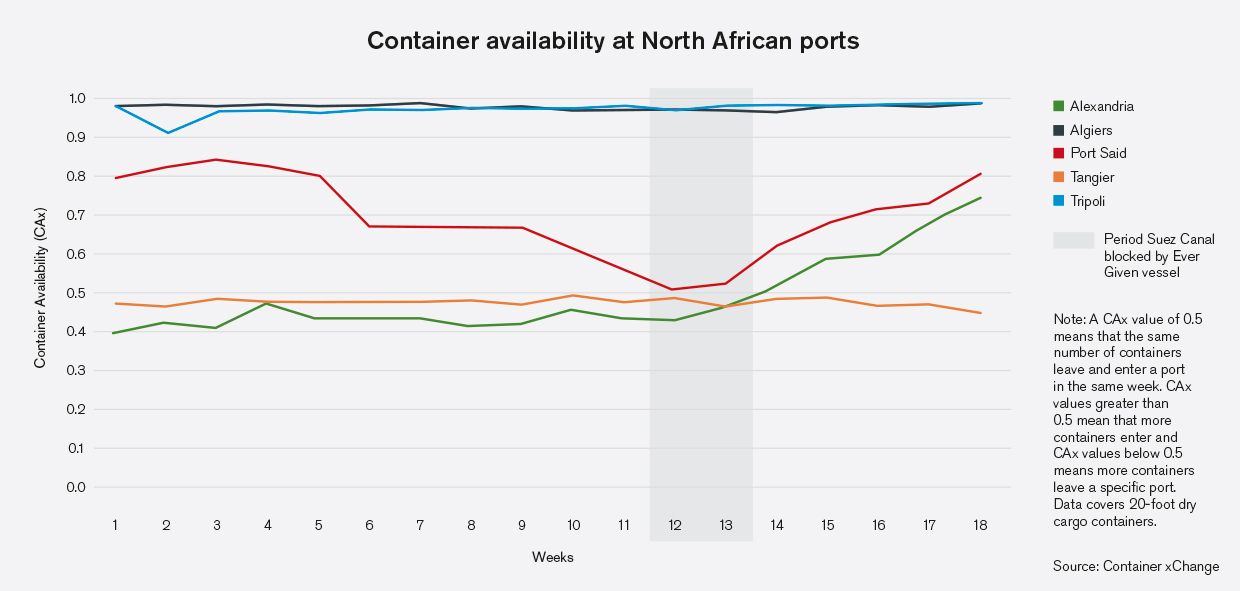

Across North Africa, data provided to GTR by container leasing and trading platform Container xChange shows the impact of the Suez Canal incident on port congestion.

In the five weeks following the blockage, the number of containers arriving at Alexandria and Port Said relative to the number leaving was markedly higher than before. Congestion also remained a serious issue at Tripoli and Algiers, though that was already the case since at least the start of the year.

The Port of Tangiers is the only North African port reviewed that consistently shows an even balance between the number of containers leaving and arriving.

A pile-up of containers north of the Suez Canal does not necessarily mean ready availability for exporters in North Africa and Europe, however.

Container xChange chief executive Johannes Schlingmeier says it is “increasingly difficult” to book export containers with European carriers, as shipping lines “are prioritising empty containers in order to move the boxes back to China as fast as possible”.

In effect, it is proving more cost-effective to ship empty containers to Asia than wait for them to be filled by exporters in North Africa, Europe or the Americas.

That has created high competition for container space among those exporters, resulting in rising freight rates. Alan Murphy, chief executive of maritime consultancy firm Sea-Intelligence, tells GTR that spot rates from Asia to North Africa appear to have been trading at a premium of 20% above Asia-Mediterranean average rates since late 2020.

“From a container shipping perspective, North Africa is served on Asia-Mediterranean services, and thus falls under the greater trade definition of Asia-Europe, and Europe-Asia on the back-haul,” he says.

“Exports out of North Africa would be competing for the same equipment and vessel space as exports out of Southern Europe, and thus subject to the exact same supply and demand forces.”

For North African importers, a further complication is that some vessels may have decided to tackle delays in their journey by skipping smaller ports entirely, says E2open’s Joshi.

“When you’re trying to deal with a delay you may often power through and bypass smaller ports,” he says. “That would typically tend to be in ports around North Africa, for example, where the carrier feels there is more value in getting to the major ports more quickly.

“We have seen some of that – though not on a dramatic scale.”