Global supply chains are in the midst of a perfect storm, writes Elizabeth Stephens, head of credit and political risk analysis at JLT Specialty.

Supply chains have been tested by the financial crisis which took a toll on manufacturing, resulting in tightened credit, weakened consumer demand, particularly in developed markets, and plentiful bankruptcies. Add to that challenging mix an array of natural catastrophes from unanticipated volcanic ash clouds and the Japanese tsunami to the expectation of US hurricane season and global supply chains have come under pressure as never before. Supply chains became global as companies sought access to metals and minerals located in far flung corners of the world and to reduce costs by outsourcing production to factories in locations with lower operating and labour costs. Supply chains have never been as extended as they are today and this global reach exacerbates their vulnerability; yet these models endure because of the ease of demonstrating the financial benefit of cost-reduction activities compared with the difficulties of making a business case for investments that improve supply chain resilience.

The importance of supply chain resilience is sometimes downplayed because of the perception that disruptions to supply chains are short-lived. This is a misperception and in reality the impact of supply chain disruption may be felt over a number of accounting cycles. Analysis of stock trends for companies that experience a breach to the integrity of their supply chain show that they were punished by the stock market for at least two years after the event. Despite this, many companies pay too little attention to supply chain risk and allow it to become the Achilles’ heel of their commercial operations.

As the global financial crisis hit, companies that were building inventory through the stockpiling of raw materials quickly found themselves overextended as demand began to collapse. As the crisis spread, it became more difficult for companies to rebalance their inventories and production schedules became erratic. As production fell, lower volumes increased unit costs and created pressure throughout the supply chain. Inventories at some suppliers rose because orders placed before the downturn were cancelled. The dearth of credit made it difficult for financially stretched suppliers to secure financing to bridge the gap, leaving even the most financially sound company vulnerable to disruption because of the innumerable supply chain interdependencies that exist within and across industries.

The impact of European and US companies filing for bankruptcy had a global impact, forcing the closure of thousands of factories in the developing world. Supplier bankruptcy caused by financial problems of customers and subsequent non-payment led to a further increase in supply chain disruption.

Global supply chains heighten the challenge of managing reputational risk at a time when stakeholder expectations have risen about issues such as quality, environmental protection and the health and safety of workers. This puts additional pressure on companies to monitor all aspects of their supply chain and to impose western operating ‘norms’ on suppliers. In practice such a scenario is difficult to achieve particularly when the impetus for outsourcing was to reduce costs.

For example, many factories in developing territories have been found to use sweatshop labour or child labour, which creates a reputational risk for western companies buying from those suppliers. In Bangladesh, in May this year, more than 1,100 workers, most of them young women, were killed when the concrete pillars supporting the eight storey Rana Plaza building in which they made clothes for UK retailers like Primark, collapsed. A survey conducted by engineers in the wake of the incident revealed that three-fifths of garment factories in Bangladesh are vulnerable to collapse, putting the lives of millions of workers at risk.

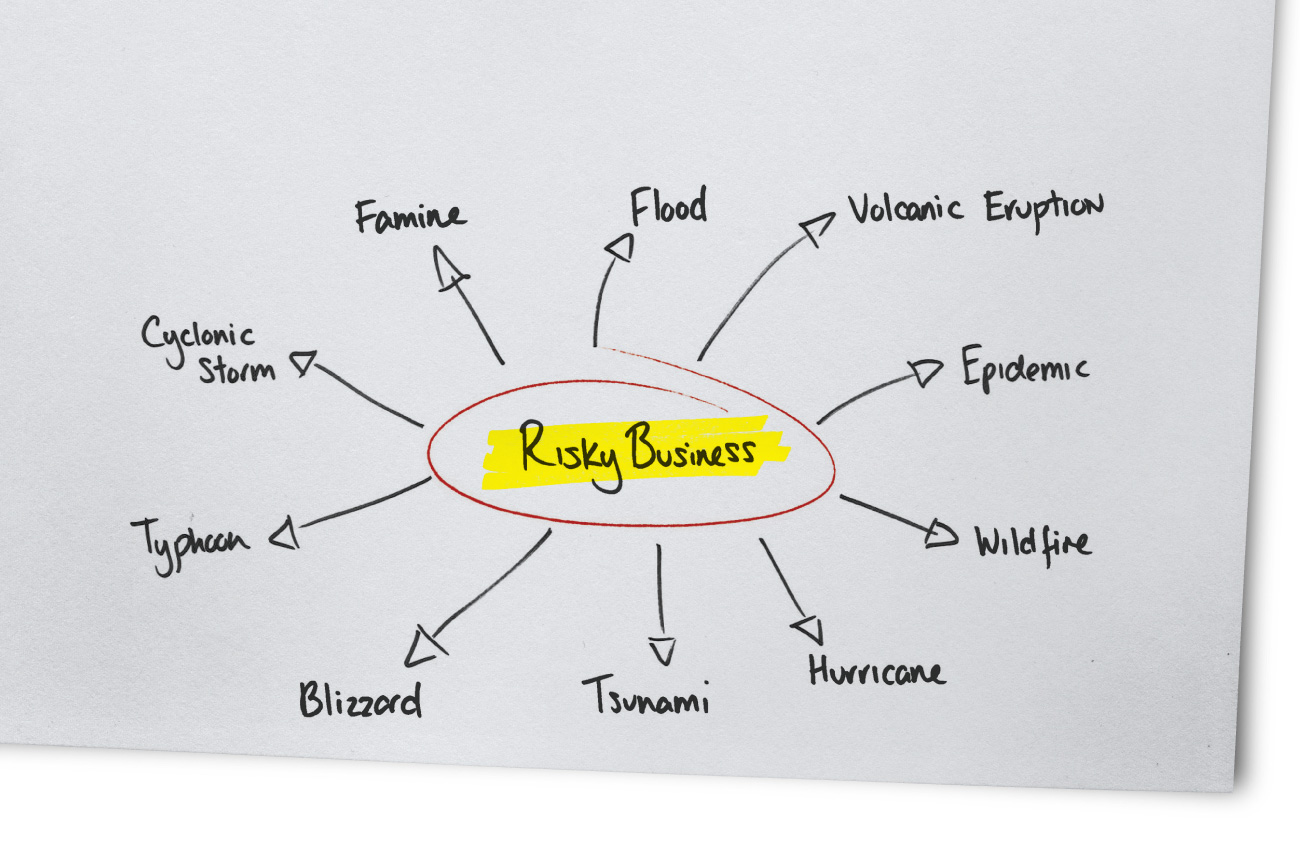

Natural disasters cause major supply chain interruptions every year. Some of these events, like the US hurricane season, are predictable in their occurrence if not the extent of the disruption they will cause. Others, like the Thailand and Japanese tsunamis, are unexpected and unprecedented in their magnitude. The more integrated a company is into the global supply chain, the more far-reaching the repercussions of natural catastrophes, in far-flung corners of the world will be.

The 8.9-magnitude earthquake that shook the northeast coast of Japan in March 2011, spawning a devastating tsunami that led to a meltdown at the Fukushima nuclear plant, provides an excellent example of the potential for environmental events to have global reach. Several nuclear reactors in the region that supplied electricity for homes and industry were destroyed and a large area was temporarily evacuated, preventing the quick re-opening of affected industries. The impact on Japanese companies soon became apparent, along with the monumental task of repairing shattered global supply chains. At the time, Japan produced about 60% of the world’s silicon for semiconductor chips. Global prices for computer memory components spiked by 20% right after the disaster. Meanwhile, a number of US auto plants were forced to halt production until shipments resumed of specialised paints and computer chips.

Estimates have been made that the disaster led to 4 million units of vehicle production being lost, the majority from Japanese car manufacturers. Production at Toyota plants fell by 50% in Japan and 40% outside the country. Disruption to Toyota’s car production contributed to the company missing profit forecasts by £620mn as a consequence of the suspension of vehicle production and a fall in sales. The World Bank estimates the earthquake and tsunami wreaked US$235bn of damage, making it one of the world’s costliest natural disasters.

As the Earth’s climate becomes more unsettled and the consequences of global warming become more apparent, the impact of natural catastrophes on business operations can only increase. While there may be little companies can do to control the weather, far-sighted organisations will prepare physically and financially and have contingency plans in place to absorb the impact of supply chain disruption.

The most effective strategy for managing supply chain risk is to identify which companies make the largest value contribution to your organisation and focus risk mitigation efforts on these suppliers. For a multinational the number of crucial suppliers may be vast. One global technology company analysed the suppliers to the top 100 revenue generators of its thousands of products and found that 600 suppliers were crucial to the production of those products. The company then tested the robustness of these suppliers and drew up detailed contingency plans for the complete shutdown of one or more of those facilities.

The adoption of a collaborative approach prior to a crisis is the most effective way to avert one. Establishing shared objectives with critical suppliers creates a unified approach to confronting risks that impact on mutual objectives. As companies globalise and their supply and demand networks separate, they lose visibility of all aspects of their competitive landscape. Therefore the establishment of co-operative relationships with suppliers is crucial if a company wants to receive preferential treatment in the event of a crisis. In turn, these suppliers may adopt a similar practice with their own suppliers, creating safeguards further down the chain.

Going beyond an understanding of the financial position of your supplier is crucial. A holistic approach should be taken to assessing the business environment of key suppliers that takes into account everything from the supply of their raw materials, currency inconvertibility and transfer issues and legal risks for suppliers operating in different jurisdictions and potential challenges posed by differing regulatory environments. It is only through an in-depth understanding of

the potential risks a supplier may face that a problem or opportunity can be identified ahead of time.

The well-documented experiences of Nokia and Ericsson in 2000 following a fire in the fabrication line of Royal Philips Electronics, their major radio chip manufacturing supplier in New Mexico, highlights the crucial role of effective supply chain management in minimising supply chain disruption. Fire, smoke and water destroyed millions of chips stored in the factory for shipment leading to the failure to supply key components of Nokia and Ericsson products.

In Helsinki, when two days after the fire a production planner who was following an established process for managing chip inflows from suppliers failed to receive a routine input, word was passed to the top component purchasing manager and implementation of Nokia’s crisis management strategy began. Realising the incident had the potential to thwart production of several million handsets, Nokia took three crucial steps to minimise the impact:

Nokia sought a major role in developing Philip’s alternative planning and Philip’s responded by rearranging its production in other factories to deliver supplies to Nokia.

A Nokia team redesigned some chips so that they could be produced in other factories. Alternative manufacturers were sought and two current suppliers responded within five days.

By having effective supply chain risk management procedures in place and activating them at the onset of the incident, Nokia averted a supply chain disruption crisis. Consumers responded favourably and in the third quarter of 2000 Nokia’s profits rose 42% and its market share by 30%.

In contrast, Ericsson, which lacked the same early warning checking procedures and pre-determined crisis management response, relied on Philips to advise them of developments and to rectify the problem, rather than proactively engaging with their supplier. As a consequence of the breach of supply chain integrity, in July 2000, Ericsson reported that component shortages resulting from the fire caused a second-quarter operating loss of US$200mn in its mobile phone division and a 3% loss in market share by year end. The crisis led to the collapse of Ericsson as an independent entity and the creation of Sony Ericsson in October 2001.