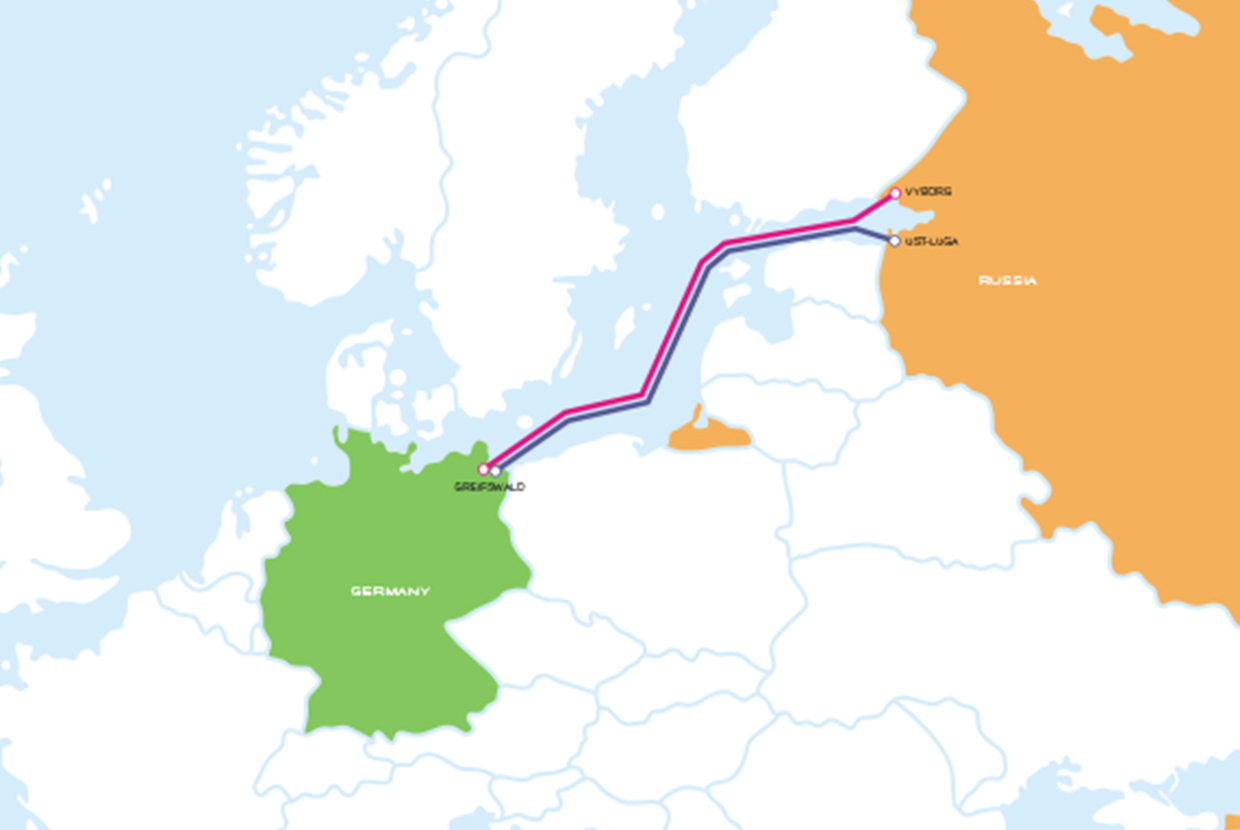

European energy companies are caught in a transatlantic diplomatic battle. Efforts by the US to stop Nord Stream 2, a vast pipeline carrying natural gas from Russia to Germany, could block millions or billions of dollars in financing pledged by EU energy companies. Are escalating US sanctions threatening the viability of the project? John Basquill reports.

Nord Stream 2 had been set to begin operations in mid-2020. The final obstacle to its construction had seemingly been overcome in October 2019, when Danish regulators approved the construction of a final 147km section running through the country’s waters.

Europe already imports around 40% of its natural gas from Russia, and a fully functioning Nord Stream 2 would supply an additional 55 billion cubic metres of gas per year – enough for 26 million businesses and homes, project backers say.

However, US opposition to the pipeline has grown in the last three years, with officials increasingly expressing concern that Europe’s energy supply could be at the mercy of a potentially hostile Kremlin.

In December 2019, the US government levelled sanctions against any European firms providing pipe-laying vessels to support construction of the project, and by July 2020, those restrictions were extended to any company providing material or financial support of any kind.

Nord Stream 2’s Switzerland-based operating company is owned by Gazprom – the Russian state-owned energy giant and the world’s largest provider of natural gas – which has vowed to finish building the pipeline by itself.

According to Russian media, construction is 93% complete, and Gazprom’s head of investor relations, Anton Demchenko, says the project will be complete by late 2020 or early 2021.

But around half of the initial financing for the €9.5bn project had been pledged by five European energy companies – Uniper and Wintershall in Germany, Royal Dutch Shell, OMV in Austria and Engie in France – and a sizeable chunk of that sum is now in doubt.

“US sanctions – if imposed – could directly hit more than 120 companies from more than 12 European countries,” says a spokesperson for Nord Stream 2.

“In an economically difficult time, the sanctions would block investments of around €700mn for the completion of the pipeline.”

The spokesperson confirmed to GTR that figure refers to investments that have been pledged but have not actually been made yet, though when contacted, none of the five European energy companies disclosed the extent to which their own investments are being blocked.

The potential impact of US sanctions extends much further than those five companies, however.

“Western European energy companies from Austria, Germany, France and the Netherlands have committed to invest almost €1bn each in the project, and more than 1,000 companies from 25 countries are fully committed to seeing the project completed,” the Nord Stream 2 spokesperson says.

“These sanctions would also undermine investments of approximately €12bn in EU energy infrastructure,” they add, citing nearly €4bn in downstream infrastructure investment in Germany and Czechia.

“This infrastructure has been constructed to transport the Nord Stream 2 gas throughout the European market. Efforts to obstruct this critical work reflect a clear disregard for the interests of European households and industries, who will pay billions more for gas if this pipeline is not built, and the European Union’s right to determine its own energy future.”

Escalating sanctions

US government opposition to the pipeline has not come out of the blue. In August 2017, the Trump administration – at that point still in its first year of government – introduced the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA), a federal bill imposing restrictions on trade with Iran, North Korea and Russia.

CAATSA gave Trump the power to impose sanctions on any entity that provides investment or other support “for the construction of Russian energy export pipelines”, though State Department guidance issued the same month said earlier projects such as Nord Stream 2 would not be in scope.

Over the following two years, hostility towards the project increased. In a June 2019 upper house hearing, Republican Michael McCaul accused Russian President Vladimir Putin of using “energy and gas as weapons against Europe”.

“There is no worse example of this tactic than the Nord Stream 2 pipeline, which would allow Russia, if it chooses to do so, to hold Europe hostage,” the Texas representative said.

There has also been speculation that the US believes its own energy exports to Europe are under threat. The State Department says in a December 2019 fact sheet on Nord Stream 2 that the availability of US liquefied natural gas (LNG) has “saved European consumers US$8bn by enabling them to negotiate lower prices with existing suppliers”.

According to European Commission data, imports of LNG from the US have increased substantially since the first shipment in April 2016. In 2019, 36% of the US’ LNG exports were to the European Union.

However, according to S&P Global analysis, there are now signs that has dipped throughout 2020. Russia is among those markets that have seen exports increase, along with Qatar, Nigeria and Algeria.

New US legislation passed in December 2019 imposed sanctions on firms involved in Nord Stream 2 for the first time, although restrictions were limited to any foreign entity that “sells, leases or provides pipe-laying vessels for the construction of any Russian-origin energy export pipeline that makes landfall in Germany or Turkey”.

The latter reference is to TurkStream, a gas pipeline stretching from Russia to Turkey that has been operational since January 2020. There are plans to extend the line so it connects with existing gas supply networks running through Southern and Southeastern Europe.

In the case of Nord Stream 2, Swiss company Allseas issued a statement in December saying it would suspend all pipe-laying activities. A spokesperson tells GTR that “all our vessels departed the Baltic Sea immediately and subsequently demobilised from the project”. Gazprom stepped in to fill the void, according to Russian media.

It was not until July 15, 2020 that the overall financing of the project was cast into doubt. Updated State Department guidance says the CAATSA sanctions “will now include investments or other activities related to a broader scope of Russian energy export pipelines, including Nord Stream 2”.

“Persons making such investments or engaging in such activities, including but not limited to financing partners, as well as pipe-laying vessels and related engineering service providers engaging in the deployment of the pipelines, may be subject to sanctions.”

That almost certainly prevents companies from providing further funds – even if contractually promised.

“If there is a commitment to provide an investment pursuant to a contract or other agreement entered into before July 15, but there has not yet been a transfer of funds, then that could still potentially be viewed as an ‘investment’ for the purposes of CAATSA,” say Bruce Paulsen and Andrew Jacobson, partner and associate respectively at Seward & Kissel’s New York office.

“Thus, any further transfer of funds or extensions of credit after July 15 could potentially implicate US sanctions.”

However, there is uncertainty over whether the five non-Russian energy companies would be able to receive revenue related to the pipeline if it is made operational by Gazprom alone.

Anthony Rapa, a partner in the Washington, DC office of Kirkland & Ellis and an expert in economic sanctions, says that is “not entirely clear”.

“You have to look at what the CAATSA sanctions do, in fact, cover,” he tells GTR. “First, they cover investments in pipelines that originate in Russia, and ‘investment’ is broadly defined under the guidance. Second, they cover the provision of goods, services, technology, information or support in relation to such pipelines.

“That suggests the purely passive receipt of investment proceeds in and of itself would seem not to be subject to sanctions, as compared to any new investment or contribution to a cash call, which would be. The State Department guidance also makes clear that any ongoing support for Nord Stream 2 and the second line of TurkStream, including repairs and maintenance, would be covered.”

Gazprom did not comment when asked by GTR whether it would take over any outstanding financing obligations for the remaining construction works, nor whether any revenue-related arrangements are expected to change.

Political backlash

As of press time, political tensions are running high. Josep Borrell, vice-president of the European Commission, issued a statement on July 17 expressing deep concern at the “growing use of sanctions, or the threat of sanctions, by the United States against European companies and interests”.

“As a matter of principle the European Union opposes the use of sanctions by third countries on European companies carrying out legitimate business. Moreover, it considers the extraterritorial application of sanctions to be contrary to international law. European policies should be determined here in Europe, not by third countries.”

And in France, senator Claude Kern has led efforts to declare a cross-European motion denouncing the sanctions against Nord Stream 2. “This is about energy, but any other sector could suffer a similar interference in the future,” he told the senate during a July committee meeting.

The five energy companies involved have been quieter on the issue, although Germany-based Uniper says “the probability of a delay or even non-completion of the pipeline is increasing”.

“In case the project can ultimately not be completed Uniper may have to impair the loan provided to Nord Stream 2 and forfeit the planned interest income,” it says in its H1 2020 financial results.

Uniper, along with Wintershall, OMV and Engie did not comment when contacted by GTR. A Shell spokesperson says: “Shell always complies with applicable sanctions and trade control measures.”

The US government remains bullish, with Secretary of State Mike Pompeo telling a July 30 senate hearing: “We will do everything we can to make sure that that pipeline doesn’t threaten Europe. We want Europe to have real, secure, stable, safe energy resources that cannot be turned off in the event Russia wants to.”

There is also hostility towards the project from within Europe. In Poland, competition regulators issued a €48mn fine against Gazprom in August on the grounds that the company refused to release documents relating to the pipeline.

The action forms part of an antitrust probe against Gazprom and the five other energy companies and follows a €39mn penalty handed to Engie in 2019.

Neighbouring Ukraine has also raised concerns that the project will allow Russia to divert gas that currently runs through its territory, depriving it of billions of dollars in transit fees – equivalent to 3% of its GDP in 2017.

There also signs further targeted sanctions could be levelled against other entities linked to Nord Stream 2. According to reports by Handelsblatt, Senator Ted Cruz has issued a warning to Fährhafen Sassnitz, the operator of Germany’s Sassnitz port.

“If you continue to provide goods, services and support for the Nord Stream 2 project, you would destroy the future financial survival of your company,” Cruz says in a letter sent in early August.

Any supply to Fortuna or Akademik Tschersky – two Russian-flagged vessels believed to be involved in pipe-laying – would become subject to sanctions “at the moment when one of the two ships dips a pipe into the water for the construction of the Nord Stream 2 pipeline”, the letter adds.

That said, Kirkland & Ellis’ Rapa plays down fears other companies could find themselves suddenly added to US sanctions lists. The lawyer says that, generally speaking, sanctions cases tend to involve outreach of some kind from the US government – particularly if European companies are likely to be on the receiving end.

“I would be shocked if a Western European company was added to the list without that sort of dialogue taking place,” he says. “That being said, if a company continued to ignore sanctions, eventually there would be significant pressure on that company to cease the activities that would be in scope.”

James Treanor, special counsel at Cadwalader, Wickersham & Taft in Washington, DC, says future action against companies involved in operating the pipeline “cannot be ruled out”.

“In that case, if investors find themselves in the position of having provided financing to a company that becomes the target of sanctions, they may have difficulty receiving payments from those companies to recoup their investment – depending on exactly what form those sanctions take,” he tells GTR.