Over the last year, Europe has had to heighten security in the face of increased internal and external threats. By the end of 2017, the region will have had four major elections. Director at Palladium Risk, Jack Harding, outlines what the five most prominent risks facing Europe mean for the region’s trade.

2017 marks the 60th anniversary of the Treaty of Rome. Signed in 1957, the treaty established the European Economic Community – the precursor to the European Union. It aimed to promote greater integration and co-operation across the continent through a customs union and to represent “future good intentions” between the signatories.

However, 60 years later, Europe and the EU are arguably facing greater challenges than at any point in their recent history. An increasingly unstable geopolitical environment has been exacerbated by political divisions at state and institutional levels. Earlier this year, EU council president Donald Tusk wrote that Europe is facing unprecedented internal and external threats; worryingly, it seems the threats are also symbiotic in that they mutually reinforce each other.

Externally, US President Donald Trump’s position on European exports and NATO could be dangerous given the threat of a resurgent Russia. Meanwhile, various parties’ involvement in Syria is exacerbating the conflict there, leading to greater migrant flows into Europe. Internally, this is putting strain on European unity and leading to a perception of an ineffectual EU response to the migrant crisis. The issue has dominated Dutch, French and the UK elections and will be a key point in the upcoming German elections. Meanwhile, Brexit represents an existential crisis for the EU that requires it to look closely at both its economic and political security.

Against the backdrop of such complexity and uncertainty, it is difficult for businesses to know exactly what to expect; this article explores five of the greatest current threats to European trade and security.

1: The US: Trade and security

At recent NATO and G7 summits, President Trump showed he has hardened his line on individual country contributions of European nations to the military alliance. He used his time in Brussels, in May, to berate member states for failing to meet the requisite financial contribution of 2% of GDP. Although the cameras showed whispers and wry smiles between the world leaders as Trump delivered the unprecedented speech, in reality, many of them will be extremely worried – and none more so than Germany.

Trump has also made strong statements about Germany’s trade surplus with the US, labelling it as “terrible” and declaring that the “really bad” Germans need to be stopped. Obviously, a US retreat from the bilateral arrangements with Germany and the multilateral arrangements with the EU would have serious economic consequences, not just for Germany, but the EU and Europe as a whole.

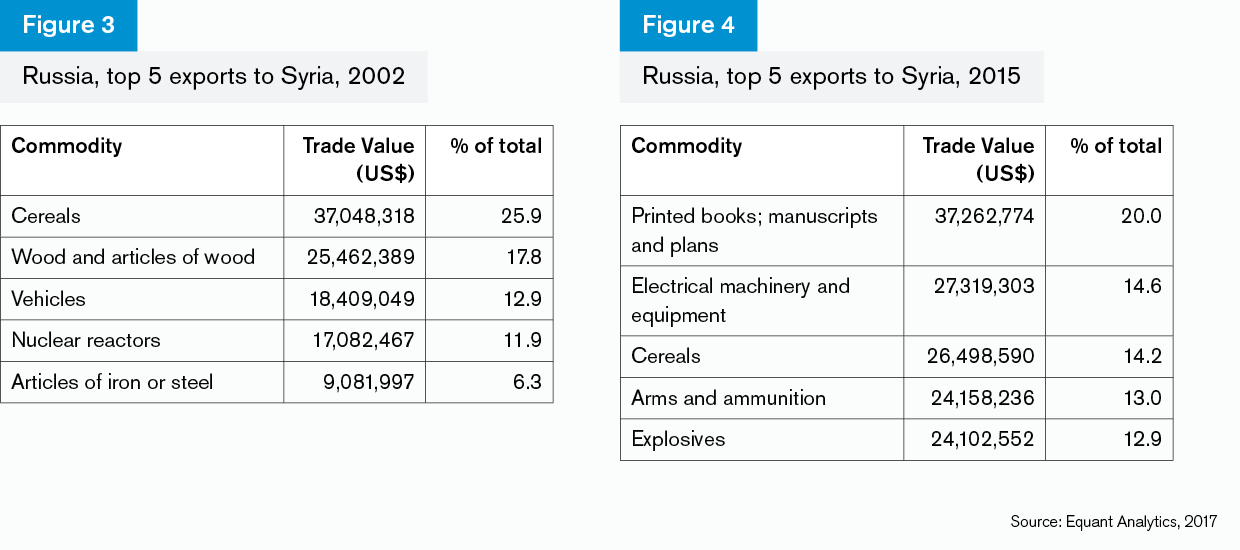

Figure 1 shows the growing importance of German car exports to the US for the EU’s economy. Following the financial crisis, German car exports rose to an all-time high of 14.4% in 2016. Using a momentum forecast (which does not factor in a possible US policy reversal) this is expected to increase to 15.1% by the end of 2017.

However, if Trump stays true to his rhetoric, this figure may drop. In value terms, even a 5% drop in German car exports to the US would constitute a loss of over US$1.9bn. Coupled with the already ailing EU trade with the US (a compound annual growth rate of -3.9% over the last five years) this would be a serious state of affairs.

Not only would a drop in the EU’s trade increase the growing public disquiet over the efficacy of the institution, it could also undermine the ability of key European economies to contribute to regional security, while also undermining Europe’s political goodwill with the US.

In short, Trump’s position is a paradox. He cannot reasonably expect an increase in the financial contribution of European nations to NATO while simultaneously curtailing trade with Europe. Trump’s mistake is viewing trade, economics and security as mutually exclusive and separate from the US’ security interests – which they are not.

2: Russia: Europe’s declining influence in post-Soviet states

In 2005, Russian President Vladimir Putin’s assertion that the collapse of the Soviet Union was the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the 20th century precipitated a deliberate policy of re-integration in many of the post-Soviet states. Russia’s stated aim is a return to “great power” status, while attempting to prevent EU and NATO expansionism. Over the last decade there has been a clear shift in strategy towards a more assertive foreign policy.

This became evident in 2008 when Russia intervened in a conflict in Georgia between pro-Russian separatists and the Georgian army. The conflict, which lasted only a few days, resulted in Russia’s formal recognition of the pro-Russian regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia as independent states, as well the creation of permanent Russian military bases in these regions. It was the first time since the Cold War that Russia had used force against another independent country and was a clear message to post-Soviet states that were considering joining NATO or increasing ties with Europe.

In 2014, the Ukraine revolution saw the country divided between pro-Europeans and pro-Russians. As demonstrations turned violent, Russia intervened and by April that year, annexed the Crimea. The war in Ukraine is still raging in the Donbass and ceasefires have generally failed to take hold.

The worrying part for Europe is Russia’s ability to undermine stability on Europe’s eastern borders. The EU responded to the Ukrainian intervention by imposing economic sanctions on Russia linked the duration of the restrictions to complete implementation of the Minsk agreements (a deal signed by all parties in September 2014).

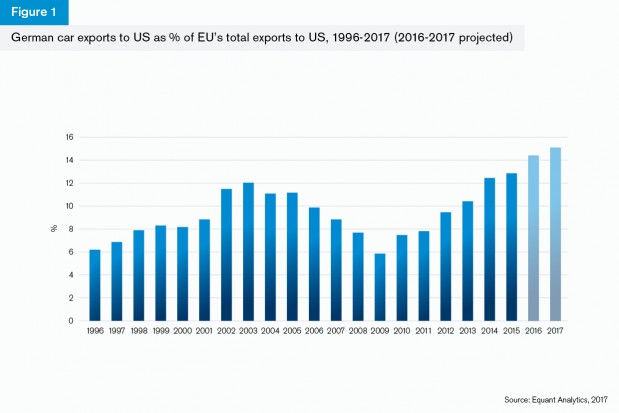

While the sanctions have injured Russia’s economy and arguably limited its ability to make further territorial advances, figure 2 illustrates its continued trade strength with post-Soviet states. The chart shows Germany, Europe’s economic powerhouse, and its trade with the region compared to Russia, and how it has consistently failed to keep pace.

3. Syria: Immigration and terrorism

In November 2015, France experienced the single deadliest terror attack in its history when 11 Islamist extremists carried out co-ordinated attacks across Paris. Investigations after the attacks showed that at least six of the perpetrators were French nationals and all 11 had recently visited Syria. The direct link with Syria highlighted the transnational nature of the threat from Islamist terrorism blurring traditional distinctions between foreign and domestic policy.

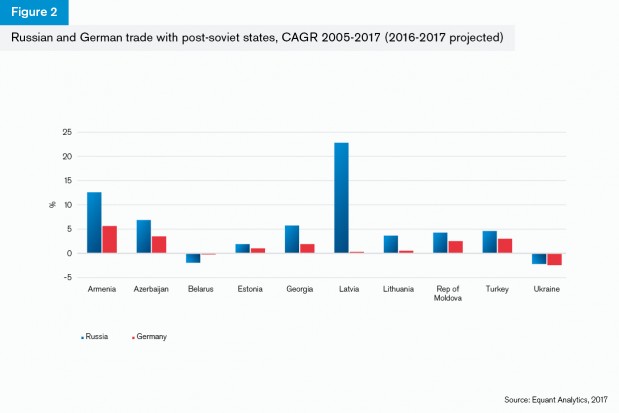

Again, Russia has played a role in the conflict. President Putin’s overt support for President Bashar al-Assad’s regime in Syria has contributed to the influx of millions of migrants over the last few years. Figures 3 and 4 compare Russian exports to Syria in 2002 compared with 2015 and demonstrate how Russia has been fuelling the conflict in trade terms. The numbers show how arms and explosives have become the fourth and fifth-largest Russian exports to Syria.

Over a million refugees entered Europe in 2015. The crisis exposed the propensity of European states to respond according to the national, rather than European, interest. Immigration quickly became conflated with terrorism and encouraged a wave of populism across the continent. Although there are expectations that IS will continue to lose ground in Syria and Iraq over the coming months, in the short term the threat from terrorism may increase as fighters return home.

Furthermore, there are worrying signs that the threat from terrorism has caused a shift in some countries’ military strategy. France, for example, has deployed over 10,000 troops across the country under Opération Sentinelle; this is 15% of the Armée de Terre’s total operational force and constitutes the largest domestic deployment of troops on French territory since Algeria in the 1960s.

It will be essential for European states to continue to co-operate on security issues and ensure that counter-terror strategies serve more than just the national interest. Given the threat of a resurgent Russia and Trump’s stance over NATO, Europe can ill afford further reductions in its military capabilities.

4. Populism, Brexit and the security vacuum

The tide of populism in Europe appears to be waning slightly in that both far-right leaders Geert Wilders in the Netherlands and Marine Le Pen of France were defeated in the recent elections. Support for Alternative für Deutschland (AfD), Germany’s anti-immigration party, has also weakened and it is unlikely that it will have much impact on the German elections in September.

There are, however, several lasting legacies of this populism which will continue to present risks for Europe in the coming years. First, populism itself is a function not just of the migrant crisis, but also of the perceived lack of democratic legitimacy and a leadership vacuum in Europe, both at EU and member-state level.

This sentiment has not disappeared with defeats for Le Pen or Wilders. In fact, anti-euro and anti-free trade Beppe Grillo in Italy continues to gain support. While Le Pen did not become president, President Emmanuel Macron’s mandate is substantially weakened by the fact that 25% of the population did not vote at all and a further 9% spoiled their ballot papers, suggesting dissatisfaction with political elites.

The other major consequence of populism is, of course, Brexit. In the near-term it is unlikely that trade will be substantially affected, because of the extent to which UK supply chains are interwoven into European ones.

However, the EU project was always a political one, with the objective of preventing conflict through shared norms and values. The risks are that the Brexit negotiations will deteriorate if the rhetorical stand-offs between the EU and UK negotiators continue.

Prime Minister Theresa May has been keen to stress that security is a key part of the future relationship to be negotiated. However, security is in the best interests of all of Europe, and Brexit will not mean that the UK ceases to contribute to European security. There are a numerous bi and tri-lateral security arrangements in place which the UK will honour.

What may change, however, is who plays the main role for security issues in the region. In other words, which European state will become the answer to the Kissinger question of “who to call to speak to Europe”?

Germany increasingly recognises its leadership role and chancellor Angela Merkel is widely viewed as the person who can take up this challenge – the only person whom both Washington and Moscow will listen to.

The fact that France and Germany are focusing their discussions in the coming months on European security policy as much as more traditional issues like the euro and immigration is important. It reinforces the point that Europe’s security regime post-Brexit will be different, with more influence concentrated in Berlin.

5. Cyber security

The final risk to security and trade is the growing threat from cyber-attacks. This is not necessarily an internal or an external threat since attribution is a notoriously persistent issue in the realm of cyber security. Pinning down the perpetrators of an attack often just leads to dead ends. However, attribution is about apportioning blame in order to politicise an attack; it in no way detracts from the severity of the threat.

A prime example of this was the global ransomware attacks in May 2017 by the so-called “WannaCry” crypto worm. In just one day, over 200,000 computers in 150 countries were infected by a worm which encrypted the users’ files and demanded 300 bitcoins for their release. The speed at which the worm spread demonstrated the crippling potential of an attack. In the UK, the national health service computers were locked out, forcing the cancellation of operations.

The issue for businesses is the increasing privatisation of security: intelligence services are not able to prevent attacks on businesses. Therefore, they are reliant on each business to provide its own security. In essence, businesses are having to become cyber security experts. This is an achievable goal for larger companies which can afford dedicated or third-party IT specialists. However, SMEs are particularly vulnerable to the threat.