The economic and political context

Asia’s trade and trade performance has been out of the limelight for more than a year now, with the world focused on Brexit and the foreign policy vagaries of the Trump administration. However, the political machinations of trade in the region are no less important in 2017 than they were in the years following the financial crisis. While we might not be talking about a ‘hard’ or a ‘soft’ landing for China anymore, there are clear consequences of the shift in its political and economic policies, which will have a large impact on the region. Similarly, and of equal importance, are the consequences of US policy in the region, including its withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP).

As a result, there are several areas of political and economic risk which also inform the context of trade in the region generally, and this trade overview in particular:

North Korea and the South China Sea

Much of the focus on risk in Asia has been in terms of the risks of conflict, intentional or accidental, in the South China Sea. The rhetoric between the US and North Korea in particular has driven an increased perception of geopolitical risk. The importance of the South China and East Seas, however, is not just geopolitical. The South China Sea is part of a key shipping route: trade between China and Japan, and China and many of its other regional partners, travels through that route. Any conflict, or even perception of conflict, is a risk to the free movement of goods around the world.

Japan

Japan’s sluggish growth and loose monetary policy (negative interest rates and quantitative easing [QE]) have weighed on policy for many years. Since the Fukushima nuclear disaster in particular, policy has also focused on using this loose monetary policy to keep the yen relatively low, with a view to boosting exports.

Since the disaster, Japan’s imports have reflected its newfound energy dependence. This should have had the dual effect of increasing inflation and restoring the country’s trade surplus. However, Prime Minister Shinzö Abe’s ‘Abenomics’ has had mixed results, and Japan’s trade still remains relatively flat. Imports continue to grow faster in value terms than exports. Since the yen has, until recently, been strong, there’s a suggestion of sustained weak consumer demand.

China’s One Belt, One Road (OBOR) initiative

China has been heralded as the new champion of free trade at the World Trade Organisation (WTO), but its policies to extend trade infrastructure through its ‘New Silk Road’ are not solely grounded in trade benefits. There are longer-term strategic interests for China in building strong infrastructure across Asia, Mena and Sub-Saharan Africa. Combined with the growing importance of the Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), China stands to benefit from the uncertainties that surround US trade policy.

Trade agreements – RCEP, Asean and TPP

In the wake of the US withdrawal from the TPP, trade’s centre of gravity is likely to swing back towards the more China-centric Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), not least because of OBOR.

RCEP comprises Asean (Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Brunei Darussalam, Vietnam, Laos and Myanmar) plus Japan, China, South Korea, Australia, New Zealand and India. In the long term, it may shift global trade away from the US. Again, this reinforces China’s strategic and economic objectives.

The size and scale of Asia’s trade and supply chains

The major global shift over the past 20 years has been to redistribute trade from developed to emerging markets. Capital inflows to emerging markets, particularly in Asia, grew significantly after the financial crisis, but had actually started to increase substantially in the mid-2000s.

Trade itself has grown exponentially as global supply chains have redistributed around the world.

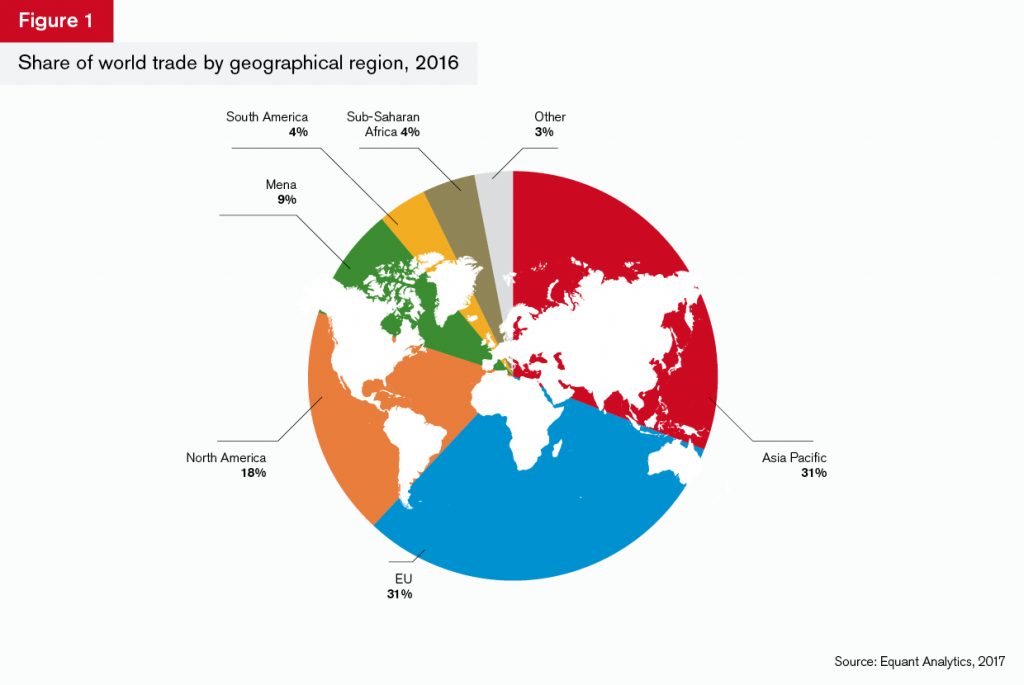

Even though Asia’s trade has slowed in the past four years, it still accounts for 31% of world trade (Figure 1).

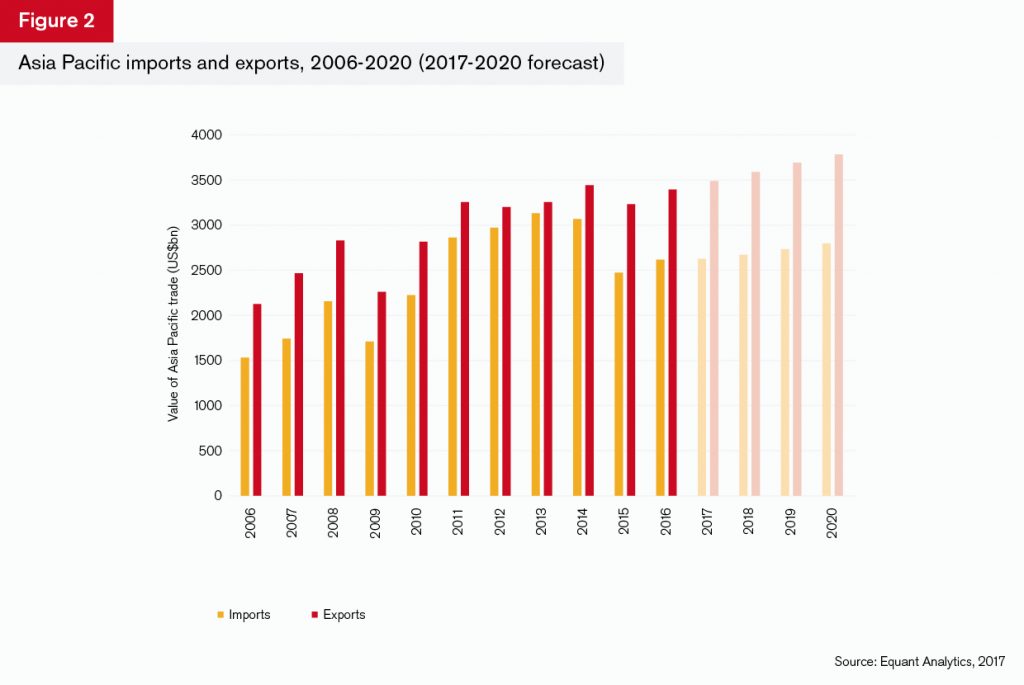

The region runs a substantial trade surplus, largely because of the dominance of China. In 2016 Asia Pacific’s exports were worth nearly US$3.4tn, while its imports were worth US$2.6tn (Figure 2).

The size of the surplus is dependent to a large extent on commodity prices. The region is a net importer of oil and gas. As a result, the surplus widens when lower oil prices feed through into import prices, as they have done since 2014.

Figure 2 also shows how China’s restructuring and economic slowdown have affected the region’s exports. Even with the financial crisis, exports were some 53% higher in 2011 than in 2006. Since 2012, the total nominal growth in exports has been just 6.2%.

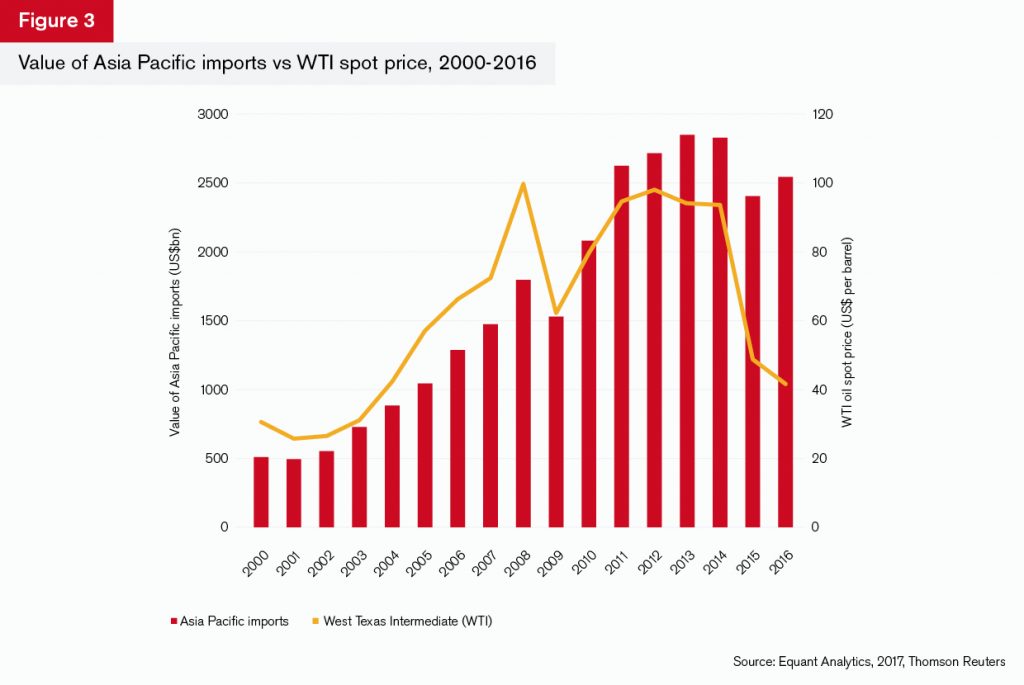

While some of this is connected to China’s slowdown, the impact of oil prices cannot be understated (Figure 3). As mentioned, this affects the trade surplus of the region, because of its dependency on oil imports.

Figure 3 shows the closeness of the relationship between oil prices and imports up to 2014. The correlation over the time period is 0.73, which is high, although perhaps not has high as might be expected given the value of oil imported (US$655bn in 2016). The relationship has inverted since 2012 and inverted sharply since 2014. This suggests two things:

- The region has potentially become more energy self-sufficient. The energy-related growth in imports in 2012 and 2013 may reflect the immediate impact of the Fukushima nuclear disaster in Japan, while the drop in the value of imports in 2014 is due to the general drop in energy prices.

- The region is increasingly importing a more diverse range of products. In other words, as China shifts towards consumption-led growth, the energy component of its imports reduces proportionately.

Low growth in world and regional trade, and low commodity prices are features of the post-crisis global picture. Global trade has struggled to grow at the rates seen immediately after the financial crisis in value or volume terms. Although Asia Pacific has generally fared better than the rest of the world, the sluggish growth is still evident (Figure 4):

- The drop in Asia Pacific trade in 2009 was slightly less severe than for rest of the world. This was in part due to the growing trend of ‘south-south’ trade, which was less interdependent with the general lockdown in credit immediately after the financial crisis.

- The subsequent growth in regional exports and imports in 2010, and in regional imports in 2011, was due to trade finance being channelled towards Asia Pacific.

- While tight credit remained evident in developed markets, the fact that trade had grown rapidly pre-crisis and recovered rapidly post-crisis made the region very attractive for inward capital flows and trade finance.

- While the growth in imports remained strong in 2012 and 2013, lower oil prices reduced the value of imports to the region compared with the rest of the world in 2014.

- The region’s exports fared relatively well in 2014 and 2016, but dropped back along with a general slowdown in GDP growth in 2015.

All of this helps illustrate the facts that world trade has been slow to grow since the financial crisis and Asia Pacific trade growth has been disappointingly erratic since 2012. There was, however, evidence that the performance of the region was improving in 2016 and, at a sectoral level, this looks set to continue into 2017 (Figure 5).

Electrics and electronics and electrical and mechanical equipment (which includes computers) are the region’s two largest export sectors. This reflects the fact that global businesses have located in the region to take advantage of cheaper but skilled labour in emerging countries such as China, and the importance of electronics, computing and machinery to countries like Japan as well. The dominance of these exports is both a function of global supply chains and local supply chains that originate in the region.

In 2015-16, oil and gas was the fastest-growing export sector, but this trend is not set to continue into 2017. This growth reflected the collapse in oil prices, and, therefore, the value of trade, between 2014 and 2015 and subsequent recovery into 2016. Other fast-growing sectors show that much of the region’s trade growth is still in sectors which can be classified as low-value or ‘intermediate’ – manufactured textiles, furniture, plastics, footwear, iron and steel and leather products are all either low-value or highly-commoditised infrastructure inputs (plastic valves or iron and steel bars, for example).

This suggests that the structure of trade outside of electrical equipment is not changing very much.

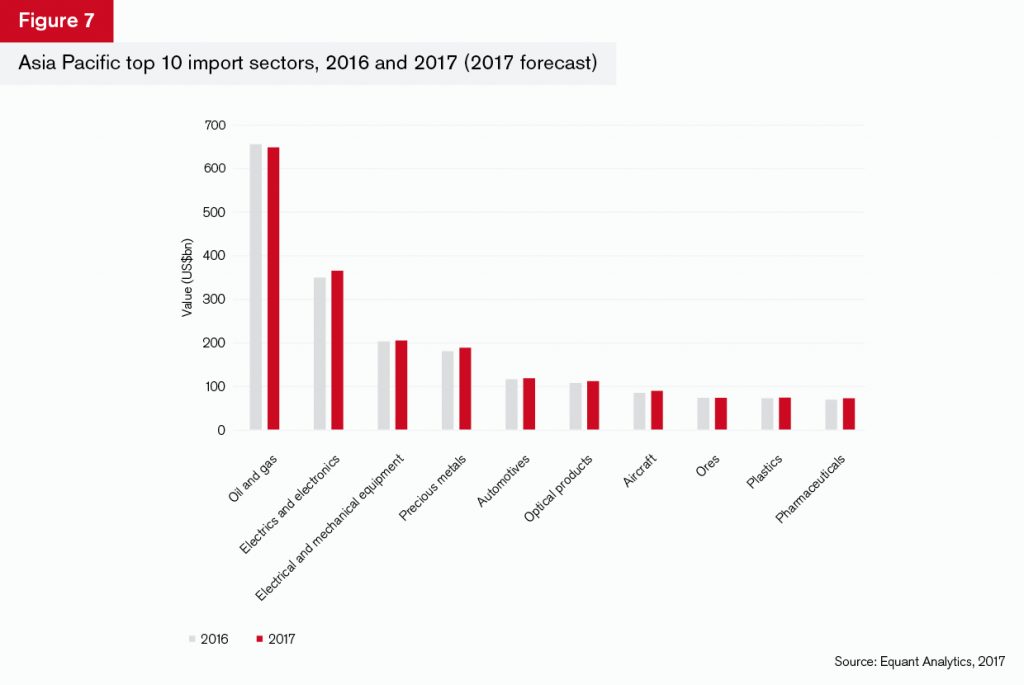

Imports suggest a similar picture (Figure 7):

- The scale of oil and gas imports is clear and highlights why the oil price has historically been correlated with the region’s oil imports. If Asia Pacific is growing, then it follows that oil and gas imports will grow, since the region has an energy trade deficit. Slower growth will mean lower oil consumption, potentially affecting the price of oil.

- The region’s second and third-largest imports are electrics and electronics, and electrical and mechanical equipment, which also underlines the importance of its supply chains, because of the composite elements in these sectors.

- Precious metals are set to grow in 2017. The largest components within this sector are gold and platinum.

- India and China have been increasing their imports of gold significantly, but China’s gold imports are now greater than India’s. In China, gold is used both in the manufacture of precision electronic equipment and, more importantly, as a store of value. The growth in platinum imports reflects the increasing capacity of the region to produce car components and, especially, catalytic convertors. This is partly, again, a function of global supply chains: global automotive companies shorten supply chains and bring component companies with them. It also indicates that indigenous capacity is increasing.

The fastest-growing sectors in the region also reflect the importance of oil and supply chains (Figure 8):

- Oil and gas was the fastest-growing import sector in 2015-16, not least because of the return to growth after the collapse in prices in 2014.

However, its growth is set to fall back in 2017, potentially because the momentum from that recovery has slowed and, more importantly perhaps, because the region is returning to greater energy self-sufficiency. - Imports across the region appear to be slowing into 2017, and this raises questions about the longevity of its recovery. Despite the fact, for example, that China’s GDP growth of 6.9% exceeded expectations in July 2017 (at an equivalent annual value), if we treat imports as a proxy for broader demand, the momentum appears to be slowing. Or, perhaps more accurately, growth in 2017 is inflated by recovery from the oil price collapse and sluggish growth in 2014-15.

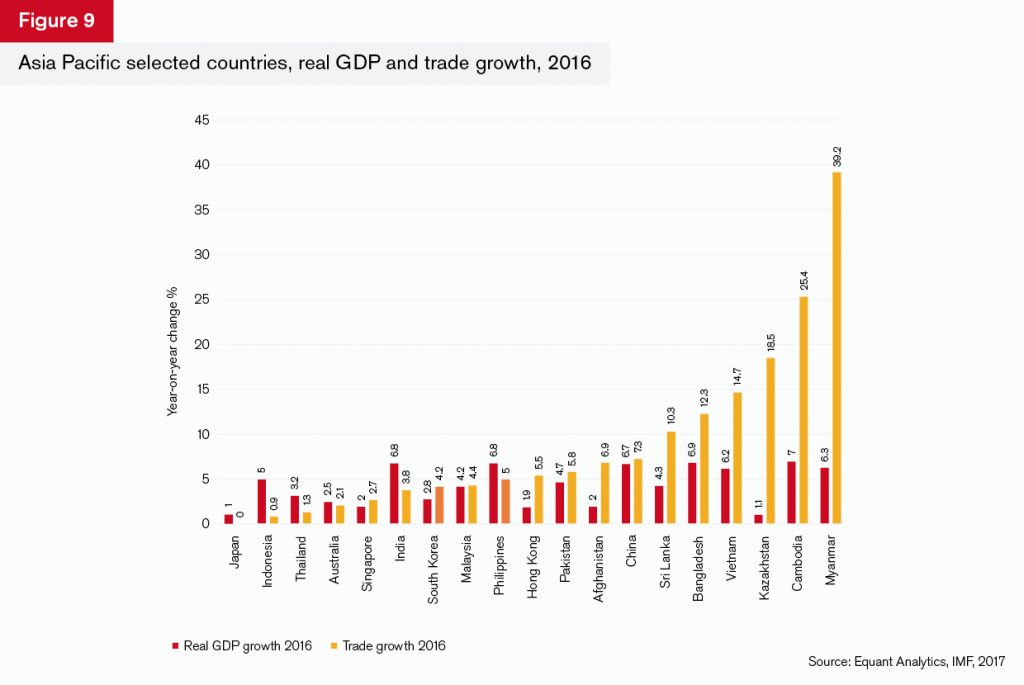

The relationship between GDP growth and trade growth in the region does not uniformly reflect the pre-financial crisis accepted wisdom that trade would grow at roughly twice the rate of GDP (Figure 9). This was also the perception for the relationship between global trade and GDP growth. For some of the lower income countries in Asia, such as Afghanistan, Sri Lanka and Myanmar, trade is growing faster than GDP growth, largely because these countries are starting from a very low base. Countries like Kazakhstan, in contrast, benefitted in 2016 from the stabilisation of the oil price and thus their trade growth, as oil exporters, is potentially artificially inflated.

There are two interesting exceptions to this – Hong Kong and South Korea. Hong Kong’s trade, intertwined as it is with China’s trade policy and its role as a port, continues to grow at twice the rate of its GDP growth.

South Korea’s trade is also growing more quickly than its GDP, which is a product of its role as the source of many regional supply chains.

Japan’s GDP growth is 1%, while its trade growth is negligible. Despite five years of Abenomics and Bank of Japan policy focused on export-led growth, the yen has strengthened since 2012. This means that the country’s exports have failed to grow at the rate needed to fuel growth and, as Japanese demand has remained weak, the relationship between GDP and trade is negative.

Other countries in the region that were seen as trade powerhouses immediately after the financial crisis, such as Indonesia, India and the Philippines, saw trade grow at less than the rate of GDP growth, while in China, Singapore and Pakistan, trade growth is slightly higher than GDP growth. Singapore and Pakistan have strong roles as ports – Singapore as a hub and Pakistan as a strategic location for China. Indeed, China’s slower trade growth can be explained in terms of its shift in policy from its own exports towards infrastructure and trade expansion through other countries within the region.

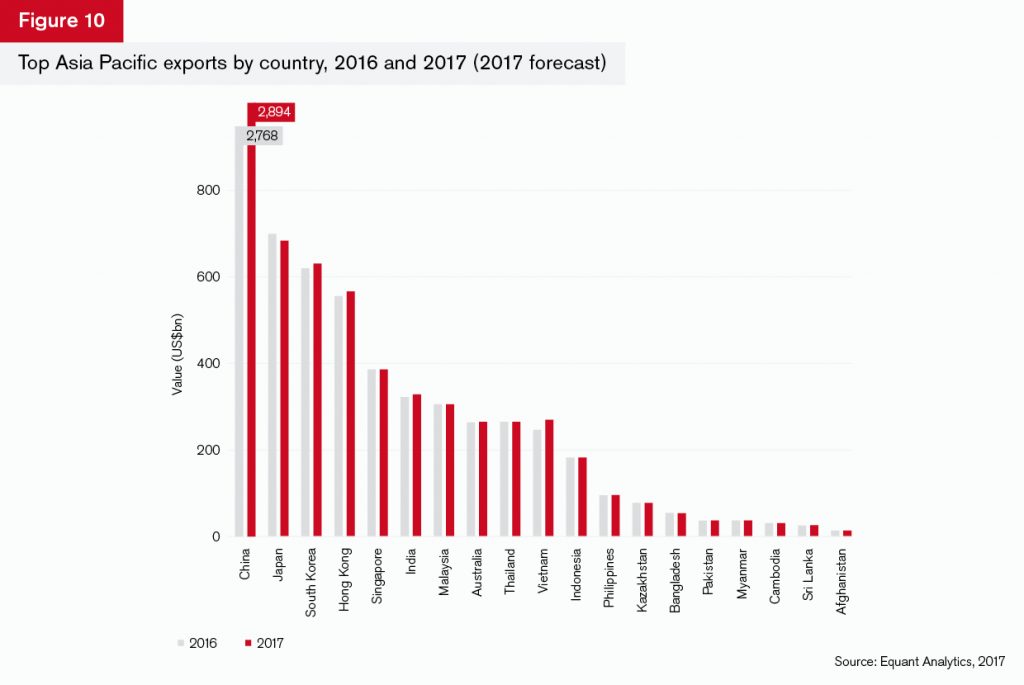

China’s influence on Asia Pacific cannot be understated and this is evident in its role as the region’s largest exporter (Figure 10).

China’s exports are nearly three times higher than Japan’s, South Korea’s, or Hong Kong’s. Smaller nations such as Afghanistan, Sri Lanka and Cambodia barely register on Figure 10, even though their exports are growing, simply because China is so dominant.

In most countries, exports look set to increase mildly, with the two notable exceptions being Japan and Indonesia, where there will be a small decline.

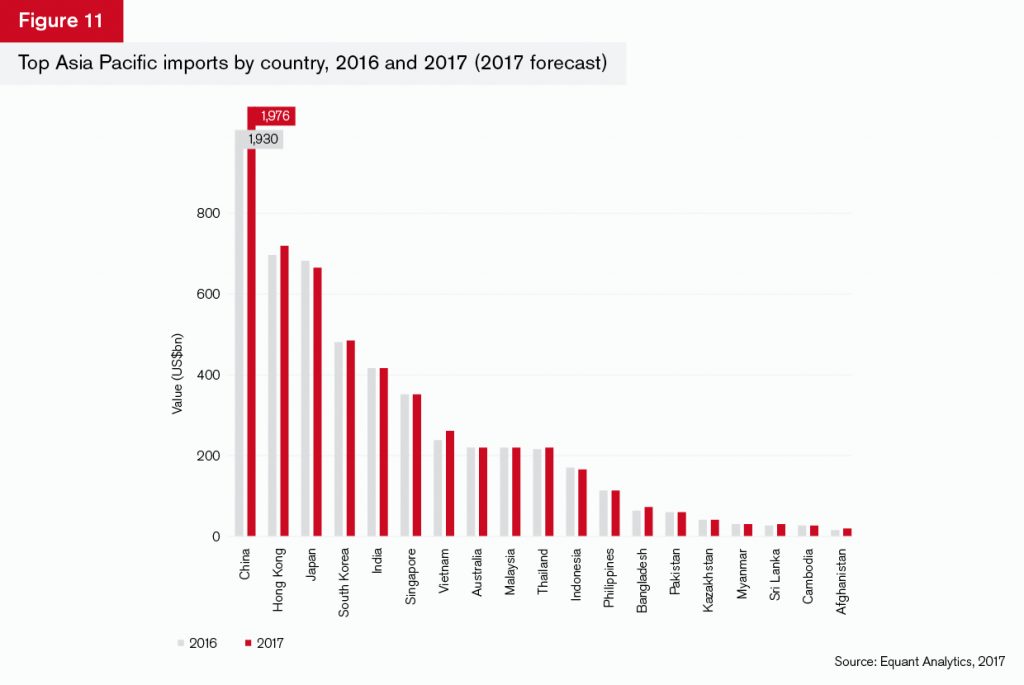

China also dominates imports and while the gap is not quite as large as it is for exports, it is still over twice the level of Hong Kong’s.

Both China and Hong Kong are showing increases in imports in 2017, suggesting that demand is growing in these places.

Japan’s imports look set to decrease in 2017, reflecting the reduced demand for oil and gas as nuclear power is re-integrated back into Japanese energy policy (Figure 11).

Summary

- Post-global financial crisis, Asia Pacific’s trade growth has been sluggish, after an initial spurt of growth in 2010 and 2011. Exports are projected to grow at an annual rate of 2.73% from 2016 to 2020, which is the same as the annual growth rate between 2010 and 2015. Imports are projected to grow at an annual rate of 1.75% to 2020, which is slower than the average 2.75% rate between 2010 and 2015.

- Trade has grown more quickly than GDP growth in some of the lower income economies of the region.

- The region appears to be becoming less dependent on oil imports, although it is still a net importer of oil and gas. The spike in energy demand in 2012 and 2013 was due in part to the Fukushima disaster, after which Japan was compelled to rely more heavily on energy imports. Its energy policy has reoriented back towards nuclear in the past year and this is reflected in lower projected oil and

gas imports. - China dominates the region’s exports and imports even though it has focused its economic policies on demand-led rather than export-led growth.

Country focus

The export homogeneity between countries in the region is remarkable. Generally, electrical and mechanical equipment and automotives dominate non-commodity trade and even at a country level, this is reflected in the top trade sectors. There is a remarkably similar pattern among both global supply chains in the region and supply chains originated in the region.

Top exporters

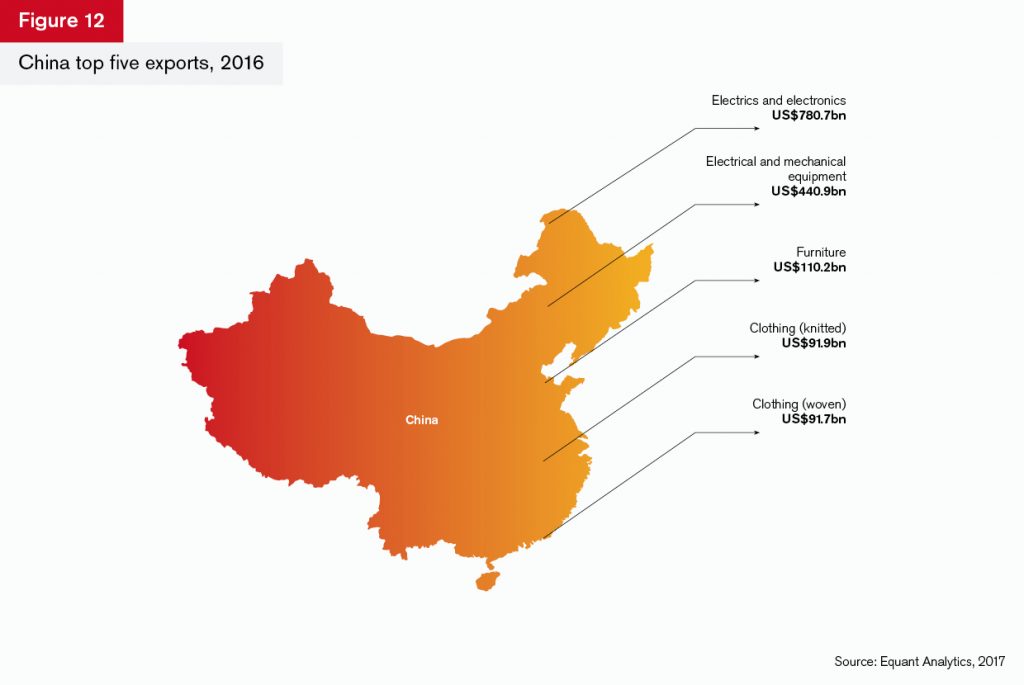

Figure 12 shows the top five exports of the region’s biggest exporting nation, China.

China

China exports nearly twice as much electrics and electronics than it does electrical and mechanical machinery and equipment. Lower value exports, such as furniture and clothing constitute just 75% of the total value of trade for machinery and components in 2016. The dominance of electrical equipment is projected to continue to 2020 with annual growth estimated to be some 4.8% each year. Given the size of the sector within China’s export mix and in the region as a whole, this growth indicates that Asia Pacific’s dominance of these industries is set to continue.

Japan

Japan’s top three export sectors are distributed evenly across automotives, electrical and mechanical machinery and electrics and electronics. Economic policy in the country has been focused on raising inflation, increasing consumer demand and, explicitly, boosting exports. While Japan remains the fifth-largest exporter in the world, its trade performance has been sluggish. In the wake of the Fukushima disaster it swung from being a surplus to a deficit nation, and while it has since restored its surplus, the projections of growth in its top five sectors over the next five years suggest that there is still much to be done. Each of the top five sectors is set to slow, with electrical and mechanical machinery set to slow at an average rate of 2% a year to 2020.

South Korea

Electrics and electronics dominate South Korea’s exports. Like Japan, the supply chains that contribute most to its trade growth originate domestically, rather than from the US or Germany. Seven of its top 10 export partners are within the Asia Pacific region. This in itself helps to explain why growth projections to 2020 are strong: the region itself will grow, not least because many countries are yet to fully realise the benefit of the economic catch-up that propelled South Korea’s growth over the last 20 years. The fact that the production of ships and boats is set to increase is important for South Korea. It competes directly with China in this market and a projection of over 3% annual growth to 2020 suggests that it will be providing the means for other countries to trade in the future.

Hong Kong

Hong Kong’s role as a port is reflected in its dominant export sectors: electrics and electronics and electrical and mechanical equipment are the first and third-largest sectors. Electrical equipment exports are nearly four times greater than metals, the second-largest sector, and set to grow at an annual rate of nearly 5%. This reflects both the importance of the sector in the region and, naturally, China’s growth. Eight of Hong Kong’s top 10 export partners are within the region, suggesting that its role is regional rather than global. The two non-regional countries that feature in its top 10 export destinations are the US and Germany, arguably reflecting the role that these countries play in electronics and automotive supply chains within Asia Pacific.

Singapore

Singapore’s exports are dominated by electrical and mechanical equipment, but oil and gas also feature, suggesting that its strategic importance to the region’s energy supply. Singapore’s fifth-largest export is optical products and this is arguably independent of its role as a port. Singapore’s research base is in the medical equipment and electronics area. Optical products is not in the top 10 imports, suggesting that this trade is built on Singapore’s domestic expertise in this sector. Interestingly, Singapore is not dependent on any one export destination. Although nine of 10 of its partners are within the region, the values traded are relatively evenly distributed between each partner.

Top importers

China

Electrics and electronics equipment was nearly twice the value of oil and gas imports in 2016, at US$521bn (Figure 13). China imports substantially more of its electrical equipment from Hong Kong than from any other partner, and this corroborates the supply chain aspect of this briefing: equipment and components come into China from other countries in the region (since seven out of 10 of the country’s partners in the electrics and electronics sector are in the region). It also re-imports electrical and mechanical equipment from itself – which may in reality be its trade with Taiwan, since this is not recorded in official statistics (China does not recognise the statehood of Taiwan). Other import sectors are dominated by infrastructure and energy requirements, reflecting Chinese growth and trade infrastructure intentions.

Hong Kong

Hong Kong’s top five sector imports are very similar to China’s. This is unsurprising given that China is also Hong Kong’s predominant export partner. Optical products is the major differentiator, and imports in this sector are set to grow by 3% annually to 2020, based on current projections. These come predominantly from China (US$19bn alone in 2016). The top imports into Hong Kong include equipment, components, machinery and energy. These reflect the infrastructure needs across the region, and reflect Hong Kong’s status as a re-export hub. Metals imports are projected to increase 2.4% a year to 2020, while imports of electrical equipment are set to increase by 4.75%.

Japan

Japan’s top five imports sectors are generally projected to increase to 2020. Although the growth levels are small, they nevertheless suggest a mild increase in demand. Oil and gas, which was its largest import sector in 2016 by some distance, will still be its largest sector by 2020, but the dependency on oil and gas imports is likely to decline as nuclear power generation in Japan becomes more important. Japan’s top four energy import partners are the UAE, Australia, Russia and Qatar. As a result, it does not depend exclusively on Asia Pacific for its energy.

South Korea

South Korea’s largest import sector is oil and gas, by some distance, and this is set to increase by 0.5% annually to 2020. The modest increase reflects South Korea’s growth, but also, potentially, a decreased dependency on fossil fuels. The major area of growth in imports for the country is in automotives, which are projected to increase by over 6% annually to 2020, but this is from a smaller base. Germany is by far the largest exporter of cars to South Korea, with some US$6.7bn-worth of German cars entering the Korean market in 2016. The US is the second-largest importer with automotives worth US$1.7bn exported to Korea last year.

India

India is Asia Pacific’s fifth-largest importer and, like elsewhere, imports of oil and gas were worth more than twice as much as its next closest import sector, metals, in 2016. Indian imports are set to grow, with electrics and electronics and organic chemicals the fastest-growing, at annual rates of 4.9% and 3.4% respectively. Much of India’s trade reflects its position as a rapidly emerging economy: electrics and electronics (which includes mobile telephony) dominates growth. However, India has a substantial generic drugs sector and pharmaceuticals are its fifth-largest export sector. The growth in imports of organic chemicals suggests that this sector is likely to become more important for India over the next few years.

Asia Pacific: external trading partners and hidden trade

Countries within the region trade with each other and the values of this intra-regional trade are substantial. This explains why much of the debate in the immediate period after the financial crisis focused on the importance of south-south trade. However, the region has also become vital to developed economies as both part of their supply chains and, increasingly, as suppliers of goods that originate in Asia, at the higher end of the value chain.

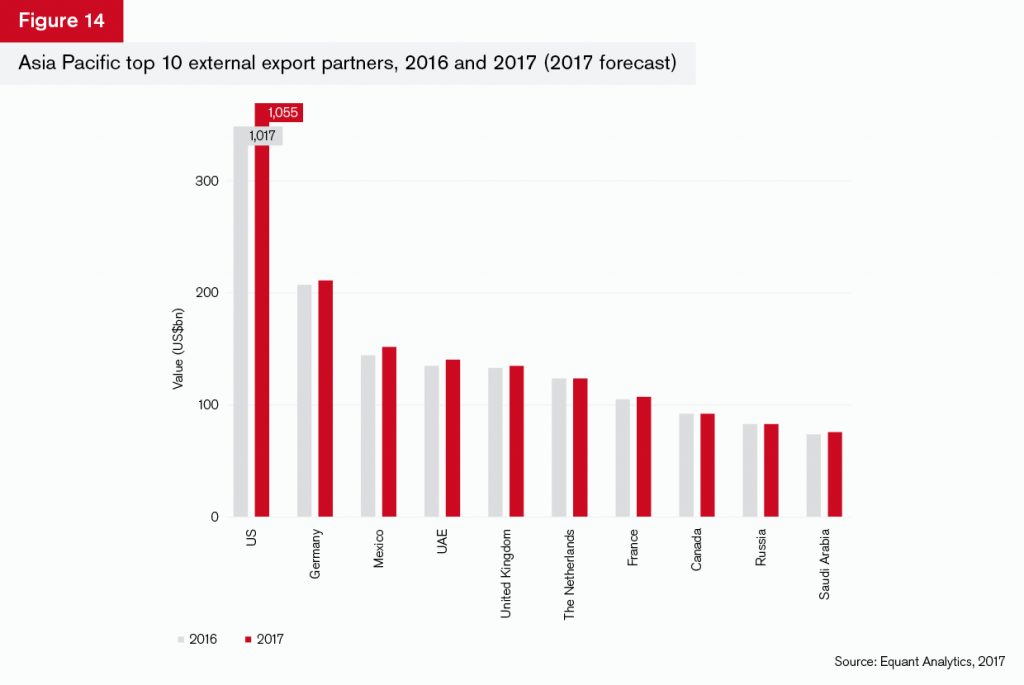

The US is the region’s dominant export partner and for 2017, projections suggest that this bilateral trade will grow (Figure 14). Exports to Germany, at US$206bn, are nearly five times lower than the US$1tn in exports to the US.

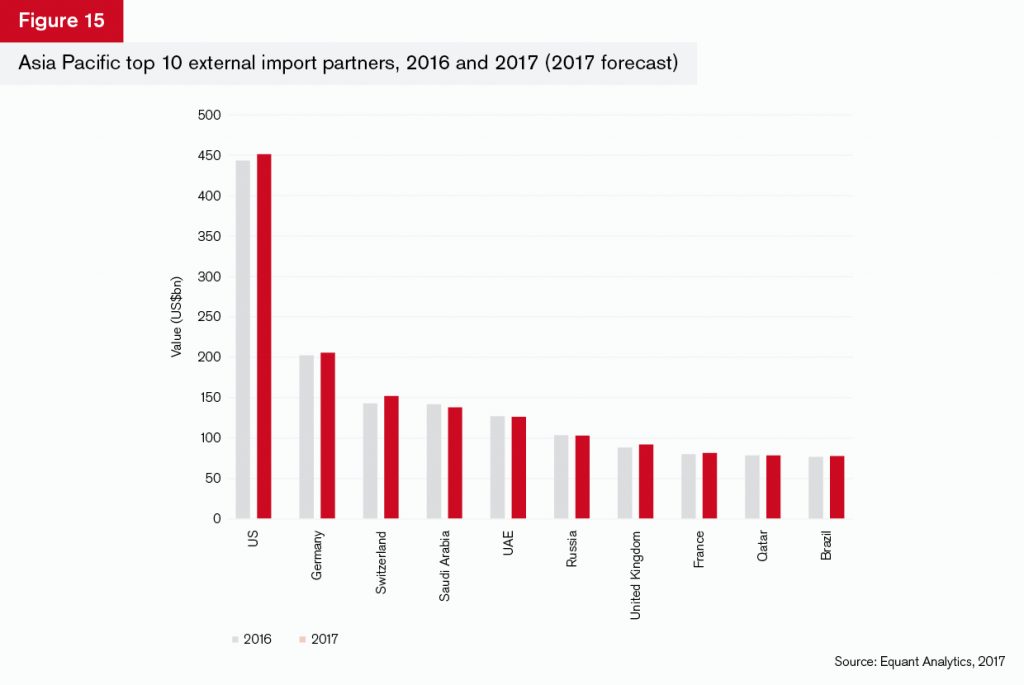

Imports are similarly dominated by the US, but the gap between the US and Germany is much narrower here (Figure 15). Imports from the US are growing faster than exports to the US, and are predominantly in electrics and electronics, and aerospace. Germany, unsurprisingly, imports cars, machinery and components. Asia Pacific runs a trade deficit with Switzerland, which is its third-largest import partner. The largest import sector from Switzerland is “commodities not elsewhere specified” (goods that are not identified by customs officials), and the second-largest is precious metals, particularly gold.

Hidden trade

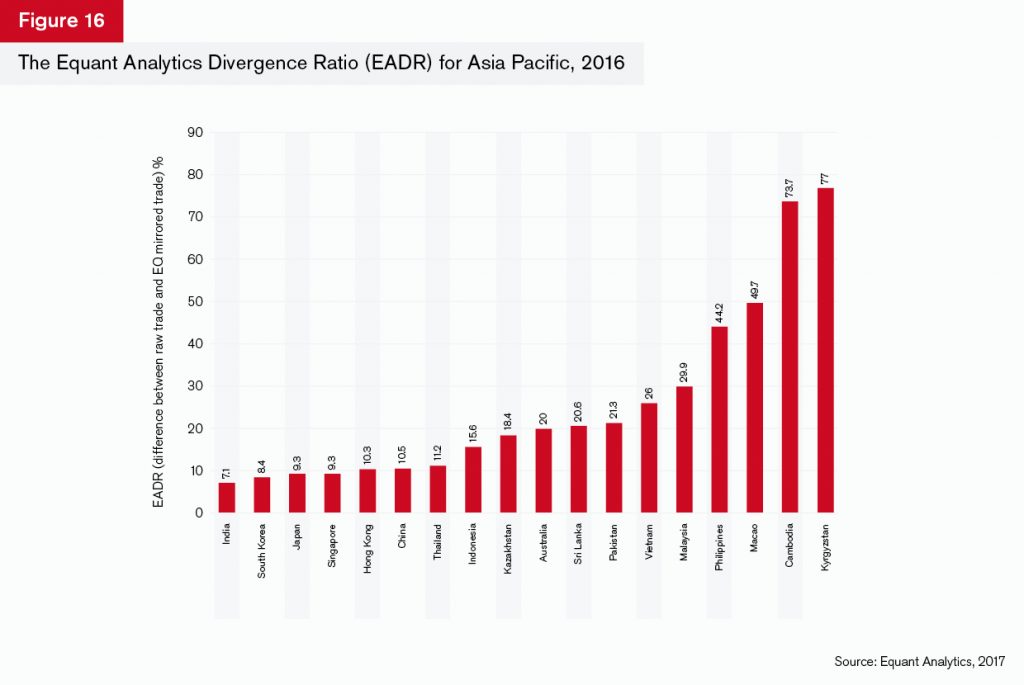

The fact that Switzerland’s top import sector into the region is “commodities not elsewhere specified” puts a question mark over the transparency of some of the data within the region.

To assess how important this is as a phenomenon, Equant Analytics uses its proprietorial data cleaning and mirroring methodology to find the gaps in the data.

Globally, this technique uncovers US$2.1tn in additional trade. Given that many of the countries in the region report data poorly, it is little surprise that the average divergence between what countries in the region say they are doing and what they are actually trading is nearly 28%, or US$1.6tn in cumulative trade (Figure 16).

Summary

- The region’s traded sectors reflect its role in global supply chains, as well as increasingly in supply chains that originate in the region.

- The majority of trade in the region is between countries in the region.

- The top five exporting and importing nations have very similar structures of trade, again reinforcing the fact that supply chains in electrics and electronics and electrical and mechanical equipment are important aspects of the region’s growth.

- The US dominates its external trade, but Switzerland, as the third-largest importer, is important as a supplier of gold, particularly into China and India.

Great power relations and geopolitics in Asia Pacific

1. China

Deng Xiaoping, China’s leader between 1978 and 1989, famously advocated a political strategy that revolved around his axiom, “hide your brightness, bide your time”. The essence of this strategy was ensuring that you do not reveal your capabilities or intentions until the most opportune moment arises, at which point there will be little your adversary can do.

China has continued to keep its cards close to its chest and, in recent years, it has been difficult to disentangle China’s trade ambitions from its wider foreign policy objectives. China clearly views the two as intertwined and part of its wider strategy of maintaining a favourable international environment. The concern is that although this is not an overtly aggressive strategy, China seems to be realising its objectives through a combination of both soft and hard power.

Given China’s traditional role as an economic power and its declaration that it will always pursue “an independent foreign policy of peace”, this harder edge is a worrying development. The apparent disconnect between China’s declared aims and observed behaviour, particularly in the East and South China Seas and along the border with India, is troubling for regional and global stability and economic prospects. As such, Chinese geopolitical strategy is at the heart of the current tensions in the region.

1.1 South China Sea

Perhaps the greatest flashpoint in the region with potentially global repercussions is the ongoing territorial dispute in the South China Sea between Brunei, China, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan and Vietnam. The dispute has its roots in competing historical claims to the body of water and the two small groups of islands (the Spratlys and Paracels) and shoal (Scarborough) within it.

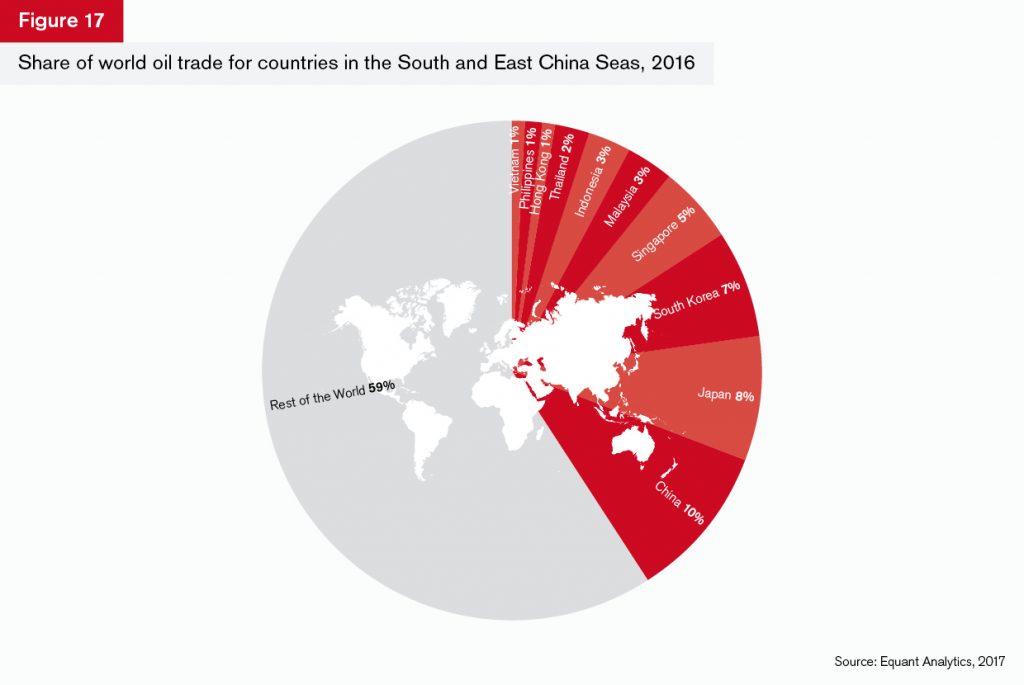

Although the islands themselves are not overly significant, the South China Sea holds great strategic importance: it is abundant in oil and gas reserves, with an estimated 7 billion barrels’ worth of oil under the seabed. It is also a crucial trade and shipping lane: roughly one-third of the world’s sea traffic passes through the area and, in 2016, the six countries involved in the dispute accounted for over 15% of world oil trade.

China’s claim to the territory stretches across the nine-dash line – an area that encompasses almost all the disputed territory. Despite the fact that in 2016 the Permanent Court of Arbitration ruled that there was “no legal basis” for China to claim the territory, China refused to recognise the ruling. It has continued to construct large military bases in the Johnson, Fiery, Mischief and Subi Reefs in order to consolidate its claims and to deter other states. However, the construction of these manmade islands is seen by competing powers as an attempted land grab. In response, other states have increased their military presence in the area. For example, Vietnam has upped its military spending from US$1.3bn in 2006 to over US$5bn in 2016 and the Philippines from US$1.6bn to US$3.9bn over the same period.

The escalation of tensions has led to a dangerous militarisation of the area. The US is heavily involved in the region and recently sailed the USS Stethem across waters claimed by China. This prompted the Chinese foreign ministry to claim that such actions “violate China’s sovereignty and threaten China’s security”. Simmering tensions have also prompted a reaction from Japan: in March 2017 it deployed the Izumo helicopter carrier to the region and in July it took part in joint military exercises in Malabar, a coastal area of Southern India, with India and the US.

This is a significant development in Japanese military strategy. The arguably unprecedented threats currently faced by Japan from both China and North Korea seem to have necessitated a departure from its post-Second World War policy of pacifism. Japan does not officially have an army, but a ‘self-defence force’, so the Izumo’s presence is a signal to its allies that it is willing to move into a more proactive military role in the interest of regional security. This is further demonstrated by the recent Japanese purchase of a large number of F-35 fighter jets.

This militarisation, along with the involvement of regional powers not directly affected by the territorial dispute (such as Japan), are causes for concern and indicative of the rising tensions in the region generally. A spillover of tensions would have dire consequences for the global economy: the countries in the South and East China Seas accounted for a total of US$10.7tn of trade in 2016, just over 54% of world trade. In addition, the countries in the South and East China Seas account for just over 40% of world oil trade (Figure 17).

Of course, a military conflict is still unlikely, but even the diplomatic crises that emerge from military exercises or territorial encroachments could have serious consequences for trade. While the US nominally retains its commitment to the Freedom of Navigation Operations (Fonops) as a tool for regional security, it has taken its focus away from the region. As the US appears to look away, China can play the long game, as it continues to build and protect what it deems its sovereign and economic rights.

1.2 Maintaining security: The North Korea problem

The perception of geopolitical risk in the South and East China Seas is not new. In the South China Sea, the disputes are historical and territorial; the role of the US has been to keep the trade route open in the economic interests of the world. However, the threat posed by North Korea is a different animal. Under Kim Jong-un’s rule, North Korea’s nuclear programme has taken great steps forwards, threatening global security in the process. Interestingly, trade still lies at the heart of the matter.

The US and China have been engaged in talks since their respective presidents held a summit in April 2017, not overtly about North Korea – but about trade. Why? US President Donald Trump explained this in a tweet on April 11: “I explained to the President of China that a trade deal with the US will be far better for them if they solve the North Korean problem!” In other words, trade could be used as a tool to gain influence over North Korea.

An explicit “trade war” between the two countries has thus far been avoided, in part, because of the post-summit “100-day plan”. Even though the deals struck since then have been modest, they have helped focus attention on trade rather than military engagement.

Keeping tensions in check is a challenge given China’s relationship with North Korea. As sanctions have become more stringent, China’s share of North Korean trade has increased (Figure 18). The momentum projections suggest that this may well stabilise over the next few years, given that China accounts for over 85% of North Korea’s trade, it has a great deal of leverage over Pyongyang.

Again, armed conflict is unlikely. The financial implications are simply too important, in terms of energy security and trade flows. Looking at the region’s trade dynamics, Hong Kong is China’s most important trading partner, with more than twice as much bilateral trade as Japan, its second-largest partner.

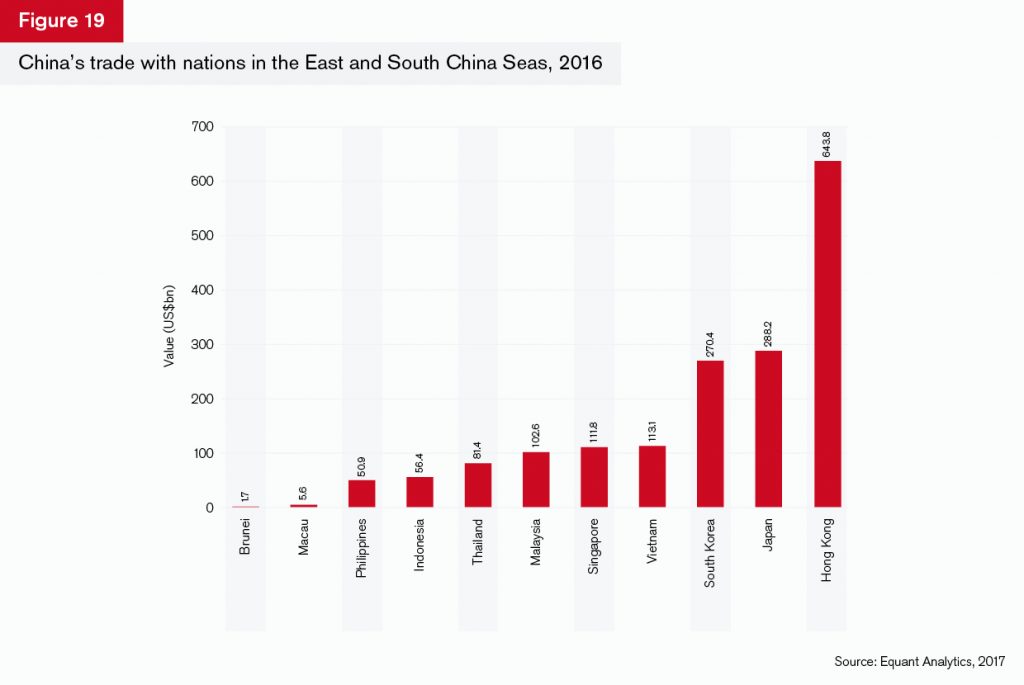

Indonesia, the Philippines, Malaysia and Vietnam are important contributors to regional supply chains in electrics and electronics and electrical and mechanical equipment, meaning that their fortunes are intertwined. As China has gone through its economic reform programme of the past few years, it is these partners which have had to adjust. But any political instability in the region threatens trade flows both there and in the rest of the world. This affects China just as much as other countries, given that trade with its South China Sea neighbours accounts for 51% of China’s trade (Figure 19). As a result, China will be keen to ensure tensions do not escalate.

Increasingly, the disputes in the region are centred on gaining greater influence. Trade, or the threat of disruption to trade, is more likely to be the means by which any conflict will be fought: it is a bargaining chip. China knows this and holds increasingly more of the cards as the US retrenches.

1.3 One Belt, One Road

The military exercises in the Bay of Bengal between Japan, India and the US served to provide a warning to China, not just over the South China Sea, but also over its role in building the Pakistani port of Gwadar. Gwadar is a focal point for China’s oil trade and trade infrastructure, and forms a crucial part of its OBOR network.

OBOR is a trade route through Asia Pacific, into Eurasia and across to Europe. The ‘Belt’ is a railway network from Asia to Scandinavia while the ‘Road’ is the old maritime Silk Road that covers the ports and shipping lanes from China to Venice. The whole project potentially involves over 60 countries – including some in Africa – 65% of the world’s population, and over one-third of its GDP. It will cost around US$1tn, with China funding between one-third and a half, according to McKinsey. It connects areas such as Afghanistan, Russia and the Crimea, India and Pakistan. The ports along the Silk Road will not just act as trade hubs: Gwadar is already earmarked as a naval base, albeit not a permanent one. As such, the risks associated with Gwadar Port are not just financial, they are also political. In Gwadar, China’s intentions to rebuild itself as a maritime superpower through trade and naval presence are made explicit.

Increasingly, trade is becoming the vehicle for China’s political ambitions. US isolationism and economic nationalism has encouraged it to speak more loudly about its support for the World Trade Organisation (WTO), and about OBOR across the region and beyond. While OBOR is a large-scale investment project, it passes through some less stable and lower income countries

China does not see its expansion as problematic. Rather, it views its role through OBOR as providing the tools and infrastructure to allow poorer countries to achieve trade-led growth, much as China itself grew over the past few decades. As such, it views itself as the champion of free trade.

Country risk analysis within the South China Sea and OBOR

Philippines

Filipino President Rodrigo Duterte was elected in a landslide in May 2016, on a ticket to combat crime, drugs and corruption. The former mayor of Davao’s approach to this mandate is controversial. For example, he called on citizens and police to conduct extra-judicial killings of drugs suspects, and thousands are thought to have died. He has explicitly stated that he wants to court China at the expense of traditionally close relations with the US, probably because years of economic mismanagement and endemic corruption have left the Philippines with damagingly high levels of debt. The country needs the economic support of China to help it establish itself as a part of the global trading system.

Terrorism and domestic conflict in the country are closely linked. The confrontation between Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) and the Moro Island Liberation Front (MILF) in the south of the country is being addressed through a peace process, but cannot

be separated from the fight against domestic terrorism and, in particular, the Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG). ASG claimed responsibility for a bomb blast in Davao in 2017, leading Duterte to declare a state of lawlessness in the country.

The fear of domestic terrorism is exacerbated through links between ASG and the Maute Group, another Islamic State-linked militia in the city of Marawi. The Filipino military has been engaged against Maute and ASG fighters, who have allegedly kidnapped 200 people, including children.

If this were not enough, the Communist People’s Party and its armed wing, the New People’s Army, is considered to be the most significant internal security threat by the Philippine government. Philippine military and police have found dealing with extremism difficult, but are now seeking to enhance the country’s counter-terrorism activity through partnerships with other Southeast Asian countries in order to reduce violence and the financing of extremism.

The country is central to the current tensions in the South China Sea, not least because it claims ownership of the Spratly Islands, which are also claimed by Brunei, China, Malaysia, Taiwan and Vietnam. In 2016, a tribunal in the Hague ruled that China’s nine-dash line claim to the South China Sea had no basis in international law, and that China’s historical claims to sovereignty on historical grounds were annulled through its ratification of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). As a result, Duterte ordered military personnel to occupy all Philippines-claimed islands in the South China Sea in April 2017.

However, the Philippines is weak militarily, as are other neighbouring countries with the exception of Vietnam. As a result, little has happened. Given the fact that current tensions are not about legal process, but demonstrations of military, political and economic influence, China has been able to weaken Duterte’s stance through offers of economic support.

Duterte is also engaged in confidence-building exercises between the Philippines and Vietnam. These include fishing rights and sea rescue exercises, as well as joint naval exchanges. The goal is to send a message to other Asean countries that there should be a united front towards China. For the Philippines, it serves to safeguard national interests by using closer co-operation to manage regional disputes. This corroborates the view that the Philippines’ foreign policy is a function of subjective nationalism and objective dependency.

Vietnam

Vietnam has become an important player within Southeast Asian trade. It is a poor country, but its financial structures are improving and its specialism in high-tech sectors, such as tablet and mobile phone production, mean that it has punched above its weight, in trade terms.

In 2014, China built an oil platform in waters disputed by Vietnam in the South China Sea. This created anti-China sentiment and China subsequently dismantled the platform after diplomatic pressure from the US.

In June 2017 the fourth Vietnam-China Border Conference was cancelled, reportedly because China was protesting Vietnam’s resumption of oil exploration in the South China Sea. Only a month earlier, the stated relationship between the two countries had been strong militarily and economically. Joint exercises were proposed and China was keen to link OBOR into Vietnam’s own infrastructure project, the “two corridors and one economic circle” policy. This was announced by senior lieutenant general Fan Changlong, vice-chairman of the Central Military Commission of China.

It was subsequently Fan who declared that Vietnam’s oil exploration in disputed territories was not acceptable to the Chinese. The fact that Fan, a military general, insinuated that Vietnam had broken the spirit of the agreement between the two countries is significant – not least because it highlights China’s militaristic intentions towards the South China Sea. The cancellation of the meeting suggests that strategic trust between the two nations has been undermined.

Vietnam has recently started to increase strategic co-operation with the US and Japan, and has resumed drilling. Of all the nations in the South China Sea it is the only one with the political will to put up a military or naval defence against China’s intentions. It has also signed a strategic agreement with India as part of India’s “Act East” programme of partnerships with countries that are in dispute with China. This saw India provide Vietnam with a US$500mn line of credit, specifically for defence purposes. An additional US$5mn is available for the development of an army software science park. This will be inflammatory to the general tensions in the region for two reasons: first, it aligns Vietnam’s defence with India which, given the tensions in Pakistan and around Bhutan, is risky. Second, it suggests that Vietnam is actively building its defences as a counter-balance to China’s activity.

Malaysia

Malaysia’s private sector is heavily indebted and labour costs are rising, although its exports are more diversified than other countries in the region. Both are a function of Malaysia’s integration into global supply chains, especially in electronics.

The ruling party since 2014 is the Barisan Nasional (BN) party, which was democratically elected. Prime Minister Najib Razak has electoral legitimacy because he won elections both within his own party and nationally. However, the opposition party (Pakatan) is aggressive and seeks to undermine BN. In 2016 Najib shored up his own position by bringing on-board a few trusted advisors as a defence against perceived opposition threats to Malaysian security and stability. The party won a number of by-elections in 2016, but governance is still unstable, increasing the country’s internal political risk.

Two major risks face Malaysia at present: the tensions in the South China Sea and internal terrorism. With regard the former, Malaysia aligned itself strongly with China in November 2016. The two navies co-operated in the South China Sea and Malaysia’s response to the tensions in 2017 has been muted as a result. However, it continues to modernise its naval fleet and has allocated US$5.9bn to strengthening national defence infrastructure. Further increases in Malaysia’s defence spending are planned as part of Najib’s perceived “vital defence of Malaysia’s territory and sovereignty”.

The country has signed mutual defence agreements with China and India, and has urged South Asian countries to resolve the current disputes without resorting to violence. Its dual alignment with China and India may seem contradictory, but it is committed to freedom of navigation in the South China Sea and believes it needs to work with partners to guarantee this.

In Malaysia, the risk of terror attacks is high. The Islamic State-aligned Abu Sayyaf group has a strong presence in the country. Along with Singapore, Malaysia is identified by supporters of IS as being part of the ‘East Asia wilayah’ or caliphate. The wilayah also includes the Philippines, southern Thailand, Myanmar and Japan, and the fact that Abu Sayyaf is building its strength and leadership could embolden radicalised individuals to act in East Asia, if they can’t travel to the Middle East.

In 2016, Malaysia explicitly stated its foreign policy mantra as one of co-operation rather than confrontation, and the fact that it is building its defences with India and China simultaneously suggests it is committed to this stance. It was a shift from its exclusively pro-western, anti-communist stance, and, at the end of 2016, China and Malaysia declared that their relations were at their strongest point. They are co-operating on Malaysian and Chinese port infrastructure through OBOR and through the Malaysian double-track railway and East Coast Rail Link.

Indonesia

Indonesia is Southeast Asia’s largest economy. However, it faces huge domestic issues that hinder its economic progress, including corruption and lack of transparency, and poverty levels which accentuate inter-ethnic and religious tensions. While it is rich in natural resources and has experienced respectable improvements in its banking sector, trade growth continues to disappoint, despite the fact that it has been a haven for inward investment for the past five years.

The current government led by President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo was elected in 2014. It controls 60% of parliament and had approval ratings of over 65% (at the time of writing). It has progressed well in its goal of reducing red tape, but governance is still an issue. For example, the government has taken a tough approach on drugs and pushed to execute drug traffickers, which has created diplomatic tensions because many of the accused are foreign.

Internal conflict centres on intolerance of non-Islamic views in the courts, which has created a climate of fear and heightened the perceived threat of extremism. In May 2017, for instance, a Christian named Basuki Ahok Purnama was imprisoned for two years for blasphemy against Islam. Many see this as a defeat for Jokowi’s efforts to grow religious tolerance and freedom of expression, which were inscribed in the country’s constitution in 1945. The case suggests that Islamists are trying to move away from secularism to an Islamic state. Part of the blame lies with the government: Jokowi did not repeal the discriminatory infrastructure that he had inherited immediately after his election, because he hoped to build relationships with moderate Muslim groups. His view was that these partnerships would help build bridges with more hardline groups, but this assumption now seems misguided.

In foreign policy terms, Indonesia is also asserting its maritime rights in the South China Sea and has said it will use the military to protect energy drilling operations by foreign vessels, which is seen as a reference to the Chinese.

Although Indonesia had not taken much of a public stance previously, in July 2017 it renamed the northern side of its economic zone as the North Natuna Seas – which was inflammatory to China, because China does not recognise Indonesia’s claims to the territories, especially those around the nine-dash line. As well as this, the military teamed up with the ministry of energy and mineral resources to provide security for Indonesia’s oil exploration. This may not be aimed solely at the growing Chinese fleets, but arguably also at other Asean countries (including the Philippines, Vietnam and Malaysia), with which there are still unresolved disputes.

Islamic terrorism is a serious risk in Indonesia, and bombings as recently as May 2017 add to the perception of instability. In July, Hizbut Tahrir (a hardline extremist group with links to the Islamic State) were banned by presidential decree with no right of appeal. Some view this as affirmative action, but others as undemocratic, since the group now has no course of appeal.

The country’s attempts to tackle international terrorism have been more positive. In July 2017 it signed an inter-faith co-operation agreement with Singapore, agreed to undertake joint military exercises with Malaysia, and signed resolutions with Pakistan and Japan to reaffirm its commitments to tackling terrorism, and strengthening security, defence and economic relationships.

Pakistan

Domestic politics are volatile, with Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif being removed from office in August over allegations of corruption, despite holding a comfortable majority in parliament. This volatility is added to by frequent terrorist attacks and the dominance of political dynasties. Furthermore, the territorial conflict with India over Kashmir has worsened. The US is a traditional ally, but relations have become strained, partly because of terrorism but also because of Pakistan’s growing ties with China. Corruption is rife, and as a result, its governance is best described as weak.

Pakistan arguably holds the key to the success of OBOR, to which the South China Sea is of huge importance. While China and Pakistan have co-operated historically both strategically and economically, the envisaged China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) will test this relationship.

CPEC is an energy, road and railway and port infrastructure project that will hook western China up to the sea, granting easier access to energy resources via Gwadar Port. But resolving Pakistan’s security and political challenges are vital to its success.

China views security and economic co-operation as being intertwined – if economics improve, so too will security and stability. Quite apart from China’s greater maritime ambitions through OBOR, another goal is to stabilise western China, and in particular the province of Xinjiang. China regards this as a counter-balance to its strategic interests in East Asia, but it is also clear that the plan has two clear areas of risks:

- Pakistan’s record on terrorism has not improved in recent years and construction sites may become targets for religious and nationalist extremists. Large-scale terrorist attacks in the province of Balochistan have killed dozens of people. There were more than 80 deaths from terrorism in February 2017. The issue is whether or not Pakistan can maintain a strong enough military presence to ensure security of all the transport routes.

- Pakistan’s political system is unstable, and power fluctuates between military and civilian leaders. Family fiefdoms dominate the country’s politics and each is vying for control of the potential trade routes, and fighting over their destinations.

In addition to this, the relationships between India and Pakistan, and India and China, will be determining factors in how the CPEC materialises. India’s relationship with Pakistan has been tense since Pakistan’s independence, with a series of wars through the 1960s and 70s. In the mid-80s, a violent secession movement of guerrilla fighters crossed the border from Pakistan into Indian-held Kashmir and since then, India has built up its military presence in the Kashmir Valley to quell the uprising

Tensions flare periodically and in May 2017 Indian forces killed a Pakistani militant who led an insurgent network in Kashmir. In the resultant protests, another militant was killed and a civilian died later in hospital from wounds associated with crossfire. Civilians were repelled with tear gas and sprays of birdshot. Beheadings and mutilations are regular features along the 450-mile disputed military frontier dividing Kashmir into Indian and Pakistani territory.

China argues that OBOR is peaceful and intended to fuel economic prosperity across Asia, west into Eurasia and across to Europe. It argues that any talk of using the Gwadar Port in Pakistan as a naval base is pure speculation. But it certainly provides China with strong access to the Indian Ocean and is the biggest single component of the whole initiative to date. It will funnel US$32bn into much-needed electricity generation projects in Pakistan. The rest of the money will be spent on transport, including railway lines between Karachi and Peshawar. These projects are altogether worth US$46bn.

There is little doubt that Gwadar Port is strategic and its development will have implications for India, the US, Iran and the Gulf states – oil will flow from the Middle East into China through the port, while it is also an obvious place for a naval and military base.

India has raised further objections to the railway part of the project going through Pakistan-occupied Kashmir, which it claims violates its sovereignty. Regardless of your interpretation of the geopolitics, CEPC and OBOR will expand China’s influence on Pakistan, while simultaneously making Pakistan more dependent on China.

Conclusion: the outlook for trade finance

Bank-intermediated trade finance (BITF) was worth over US$3.6tn in 2016 and grew at a rate of over 1% compounded every year since 1996. In some years, the growth was significantly higher – between 2003 and 2016, for example, the annual growth rate was above 11% (Figure 20).

The momentum projection for BITF into 2017 and beyond shows a slowing trend, not least because of the erratic nature of trade finance in the period since 2012. This may seem puzzling, given the likely investment across the region as a result of OBOR, but there are several important factors that will determine the realistic value for trade finance in the future:

- Rapid growth is unsustainable. The double-digit growth in BITF from 2000 up to 2011 reflects the rapid pace at which Asia Pacific, or more accurately China, was being integrated into the global trading system. The rapid pick up after the global financial crisis was the result of the relative independence of its financial system from the rest of the world and, hence, the availability of credit in Asia, when it had dried up elsewhere. Future growth of over 3% annually to 2020 suggests that this catch-up phase has stabilised and that the region is now growing on a steady basis.

- Tighter regulatory and compliance structures since 2013 have restricted the flow of trade finance to Asia Pacific, with regulators clamping down on anti-money laundering and know your client (KYC) regulation application. The fact that the region has a substantial amount of hidden trade may also have affected trade in the region disproportionately.

- Asia Pacific is dominated by small businesses, outside of China, Japan and South Korea. These businesses will be important as OBOR develops. The AIIB, the Silk Road Fund and the BRICS Bank will all play a significant role in achieving OBOR’s goals, but the key measure of its success will be the extent to which SMEs can be incorporated into the project. These entities will never contribute the rapid growth in trade finance that was evident as China integrated into the global trading system, but they will enable trade finance to continue to grow at a substantial pace.

Final remarks

The region includes some of the largest trading nations in the world, including China, South Korea, Japan, and India. Throughout the era of globalisation, it has become a fully-integrated part of the global economic and trading system in terms of both supply chain and trade finance.

There are upside and downside risks to the material in this trade outlook, however. On the upside, OBOR promises opportunities to integrate some of the lower-income countries into the region’s trade and offers investors, financiers and businesses from developed nations the chance to participate in a huge investment project.

It is the downside risks that will affect the success of future trade integration and trade finance growth. Despite China’s intentions to widen access to trade through the region, its explicit military and strategic tone, alongside its own exercises in the South China Sea, suggest that there are big political risks that accompany the economic development.

How current tensions develop will be vital, not just for Asia Pacific, but for the whole world.

Rebecca Harding, Equant Analytics