With technology as a driver and institutional support as a mechanism, Africa has the chance to set the pace for the future of trade across the world, writes William Hunnam, co-founder of Orbitt, Africa’s first digital deal origination platform.

Africa is uniquely placed to trade with growing markets in the East, established markets in the West, and domestic markets on her own continent. In order to benefit from the ensuing economic advantages, the continent’s financial institutions have started to tackle the unmet demand of Africa’s trade finance gap, currently estimated at US$120bn by the African Development Bank (AfDB).

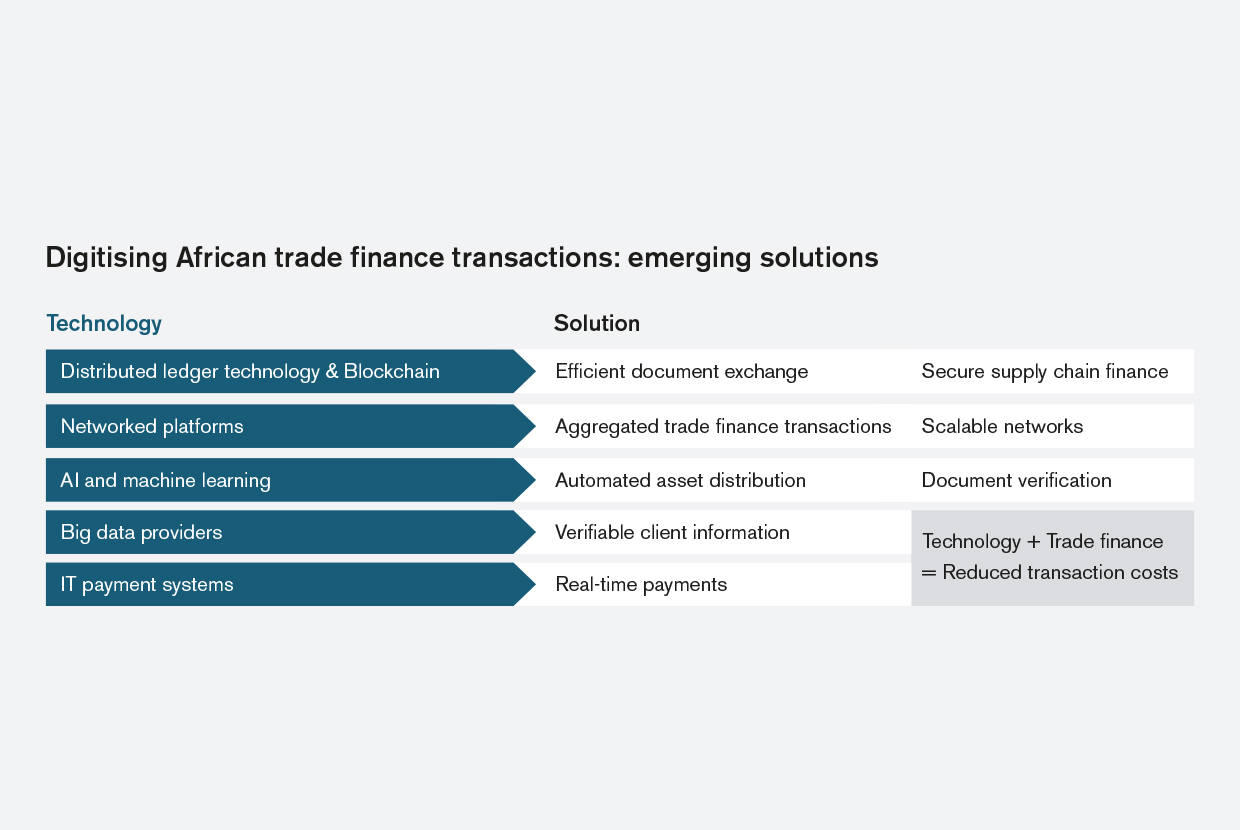

A number of wholesale trade finance initiatives have been brought to the fore, aimed at unlocking intra-regional trade to boost economic growth. But emerging technology offers a timely opportunity to anchor the continent’s top-down approach with a nimble, efficient and bottom-up solution.

Finding the African trade finance gap

The traditional overdependence on banks has led to a skewed distribution of funding to the continent’s growing trading businesses. Domestic and international banks still account for over 30% of total trade transactions in Africa, while the amount of bank-intermediated trade finance devoted to intra-African trade is estimated at just 20% of the continent’s total trade, according to the AfDB.

The continent’s leaders and investment professionals have several options for tackling the trade finance gap. Much of the attention to date has either been on the already-bankable, large African corporations or the international companies with banking lines overseas.

Little has been said about the SMEs who are locked out of their local banking systems with limited access to alternative funding options abroad.

With this in mind, we at Orbitt are of the opinion that by zooming in to understand the obstacles to trade faced by SMEs in Africa, it is possible to develop bottom-up solutions to address these challenges.

The barriers for SMEs

A recent report by Bain & Company forecasts intra-Africa trade to grow at 5.3% between 2016 and 2026. SMEs, and in particular businesses with revenues of over US$1mn, are expected to account for a significant percentage of this growth. These enterprises contribute to a large proportion of Africa’s trade, but even though 88% of African SMEs have a bank account, only 25% have a loan or a line of credit (AfDB). A similar IFC report calculated the finance gap (across all types of finance) for the 44 million micro, small and medium-sized enterprises in Sub-Saharan Africa to be US$331bn.

There are several reasons for the difficulties faced by SMEs in accessing trade finance:

- High complexity and low-scale nature of most Africa-based SME trades

- Poor documentation and a lack of client credit data

- Lack of depth in financial skills and tools to identify options and execute a successful funding process

- Limited resources and knowledge in engaging a specialist team of advisers to support the fundraise process.

There are also a number of other constraints from traditional banks that restrict access to trade finance for growing businesses:

- Stringent and often drawn-out credit assessment periods

- Rigid conditions relating to scale

- Unmanageable collateral requirements

- High cost of capital, especially when US dollar denominated.

- Can’t bank on the banks

Banks are the most important source of finance for businesses in Africa, much the same as in the world’s most developed economies. The AfDB’s recent survey of 900 African banks revealed that over 30% of the continent’s total trades are bank-financed. An estimated 68%of these trades were off-balance sheet transactions, such as letters of credit (LC). The remaining 32% of activity was on-balance sheet transactions, such as short-term loans.

But the traditional relationship-based corporate banking model is costly to operate when dealing with medium-sized businesses and smaller loan tickets. This explains why most SMEs struggle to access the required funding to support the growth of their business despite having a bank account. Neither international nor local banks are able to invest in relationships with these SMEs because lending is often costly and at times uneconomical.

The issue is often more complex than simple banking economics. In many cases the fundraise process is frustrated and often blocked by an information asymmetry. This is due in part to a lack of supporting financial information which limits the bank’s ability to offer lending facilities to SMEs. Smaller businesses may lack the required data such as a credit history or audited statements. An absence of these records prevents banks from assessing the cash flow situation of any given company.

Banks are also focusing on their most profitable clients in light of international banking regulations. As well as a need to comply with strict due diligence requirements, banks must hold higher levels of capital reserves to offset the risks they take. The Basel III reforms have reduced the amount of capital that banks are able to lend. The losers here are the smaller and less profitable business lines, in other words the SMEs.

A growing asset class

The combination of growing SME demand for trade finance and the constraints faced by African banks is a major contributing factor to the emergence of private credit as an asset class in Africa.

Taking on debt to grow the business is becoming increasingly attractive to African company owners, especially among low-cap to mid-cap companies. This is due in part to a wider range of financing options that have been relatively inaccessible to businesses across Africa up until recently.

Alternative lenders are frequently able to offer funding at 18% – as opposed to a bank that may offer 25% – which is eminently appealing for a business looking to raise capital.

Investors are also seizing the chance to deepen Africa’s trade finance landscape by providing credit-constrained businesses with the required type of capital for growth. This is more attractive given the lower risk profile of short-term financing as a result of increasingly lower rates of default.

Regardless of the size of the opportunity, institutional investors, banks, importers and exporters face the challenge of assessing and finding the right counterparty during the investment process. This is further complicated when African company owners don’t know where to start looking for investors, and even greater for those seeking their first sizable credit facility.

Enter trade technology

We see the potential for all parties within this ecosystem to leverage technology.

In removing friction points and repeated processes, Africa-focused investors, intermediaries and businesses can reduce their overall transaction costs. This is applicable across the transaction cycle from deal origination through to due diligence and transaction management up to deployment and portfolio management. As much as technology can provide the necessary tools to save time and improve efficiency, it also opens up the possibility for banks and non-bank players to better collaborate on deals, thus improving and increasing capital deployment.

Technology is widely used to support the internal trade finance processes of African banks, DFIs and alternative lenders. The digital tools that they deploy range from Microsoft’s basic suite of programs to the more sophisticated systems such as Ecobank’s OMNI eFSC (Electronic Financial Supply Chain) software. However, these solutions exist in silos with disjointed usage and application, thus representing digital islands.

By harnessing network effects, counterparties can further optimise their shared and proprietary value. In real terms this means faster, broader and more efficient provision of trade finance products to growing businesses in Africa.

There isn’t a one-size-fits-all technology solution to Africa’s trade finance gap. Networked platforms need collaboration and significant investment from all the participants in the ecosystem. For Africa this means the banks, DFIs and government bodies. A strong digital trade network would also encompass the regulators, trading companies, logistics hubs, shipping firms, financial service providers and customs authorities.

The onus should fall on multilateral institutions to take the responsibility and assume roles of ‘supernodes’. The best placed organisations to do this are the DFIs (inherently development-focused) and large banks (capital-abundant).

These actors have the sufficient scale to coordinate and invest in technologies that can help them attain the penetration they are mandated to realise. As a by-product of increasing access to shared financing and collateral information, the network will be able to help its individual participants reduce their risk for future transactions.

A ‘supernode’ should also be able to share information between a regional bank, government port and company network. The company network tracks the flow of goods and customs documentation; the bank tracks relevant data to the borrower and end buyer.

The potential to increase intra-African and inter-regional trade using this approach is substantial. Especially when we envisage that these processes can take place within a networked platform using blockchain technology, leveraging Africa-focused data resources and implementing smart payments solutions. Together with our users, we have built Orbitt to provide this secure, digital environment where all players within the ecosystem can connect, interact and transact.