Rebecca Harding, CEO of Coriolis Technologies, discusses Sub-Saharan Africa’s trade performance, its projected growth and developments around intra-Africa trade.

GTR: How is Africa’s trade faring, and what has been the impact of recent oil prices?

Harding: 2018 was a disappointing year for trade and economic growth generally, but for Africa in particular. At the outset of 2018 there was a great deal of optimism from the IMF, the World Trade Organisation, and even the International Chamber of Commerce, that trade was beginning to pull away and starting to fuel economic growth globally. But by as early as July 2018 the IMF was predicting a heavy downside risk to its optimistic forecasts, with particular effects on emerging markets.

Last year the GTR+ Africa Trade Briefing reviewed this evidence alongside Coriolis’ trade and trade finance data. It came to the conclusion that although there were significant internal risks within African nations themselves, it seemed that many of the fiscal reforms that were necessary in individual countries were being implemented. Sub-Saharan Africa’s economy overall, it argued, had recovered reasonably well from the drop in oil prices in 2016; its vulnerability to oil price shocks seemed lower than, for example, in the Middle East and North Africa; and there was evidence of strong reform programmes and a focus on free trade across the region.

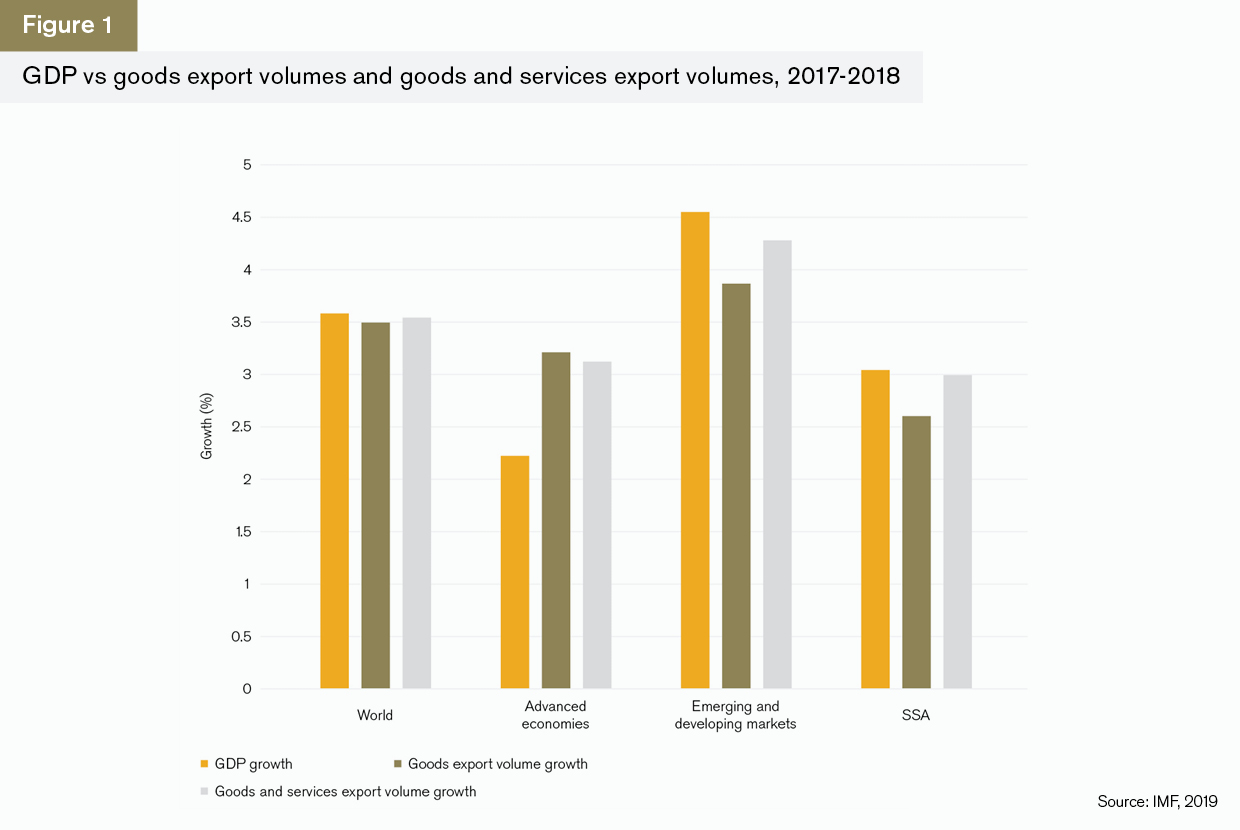

However, GDP growth in Sub-Saharan Africa in 2018 was lower than expected, at 3%. This was lower than global growth during the year, which stood at 3.6%, as well as growth in emerging markets, at 4.5% (Figure 1). While the emerging markets growth figure is distorted by more rapid growth in the two largest economies, China and India, the figure of 3% growth for Sub-Saharan African is low compared to all except the advanced economies.

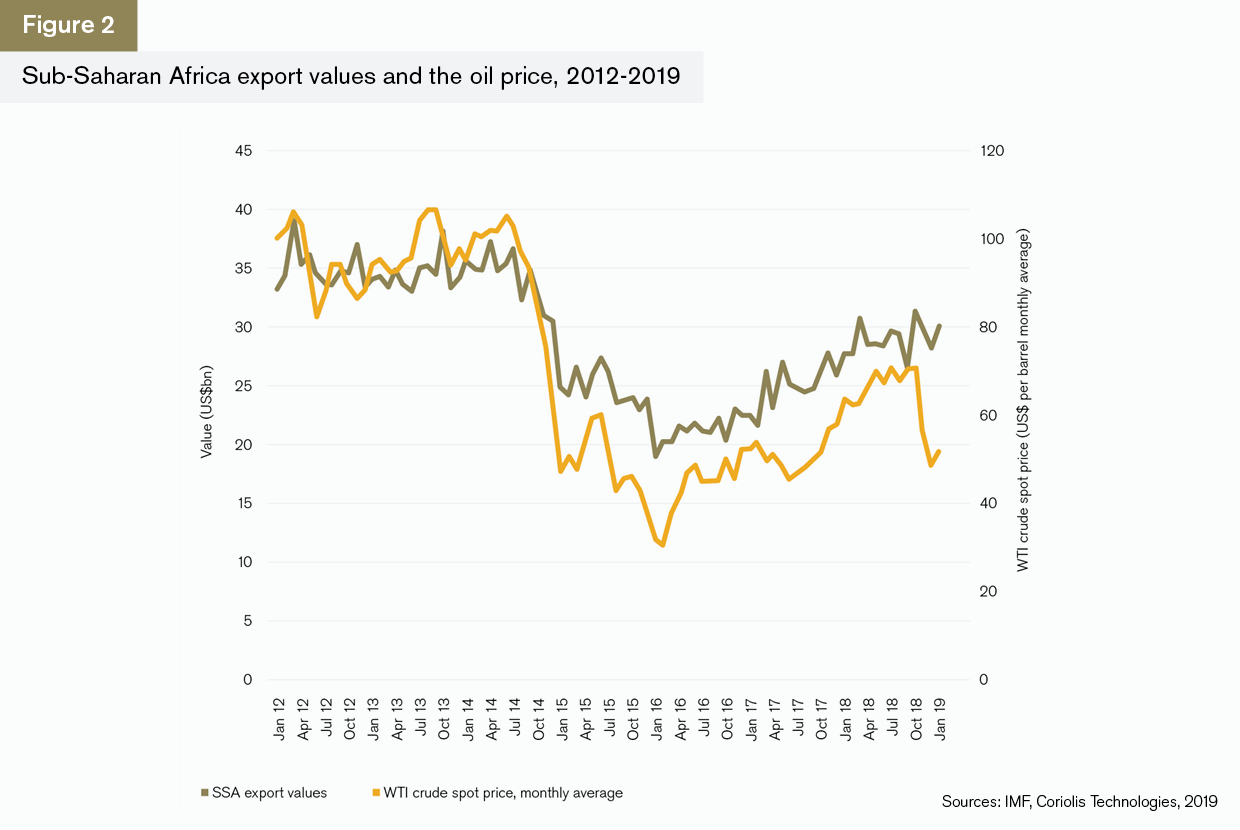

Oil prices have risen substantially since towards the end of 2017. Given that Sub-Saharan Africa’s export values are so highly correlated with the oil price, at 93%, the fact that goods export volumes have not grown as fast as GDP indicates that the region’s oil producing nations are not exporting as much as they were historically, despite the fact that trade values have recently increased (Figure 2).

This dependency on oil is inevitable: Sub-Saharan Africa’s exports of oil and gas were some US$171bn in 2018 compared to US$77bn in precious metals, which is the second-largest exported commodity. Nine out of 10 of the region’s top sector exports are in raw materials and this is characteristic of an emerging economy. It does, however, make growth through diversified exports very difficult without substantial investments in infrastructure and economic and political agreements that fuel free trade.

The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) as well as China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) offer a real chance for the continent to start to build infrastructure that fuels growth.

Intra-African trade is known to be under-reported by anything between 11%, according to the World Economic Forum, and 40%, according to economic surveys. The Coriolis estimates of the difference between what countries report and what they actually trade are above the world average of 11% for all countries and as high as 133% in South Africa. Intra-African trade is estimated to be worth around US$170bn. In other words, so much of the trade between African nations is informal and under-reported in international statistics that there is little way of knowing precisely what is happening on the ground.

Intra-African trade is important as a policy priority to fuel much-needed economic growth and development. It is dependent on political and economic stability across the continent, and while the picture for this started to look brighter last year, there is clearly still a long way to go.

GTR: Which countries in particular are seeing an increase in their trade performance and why?

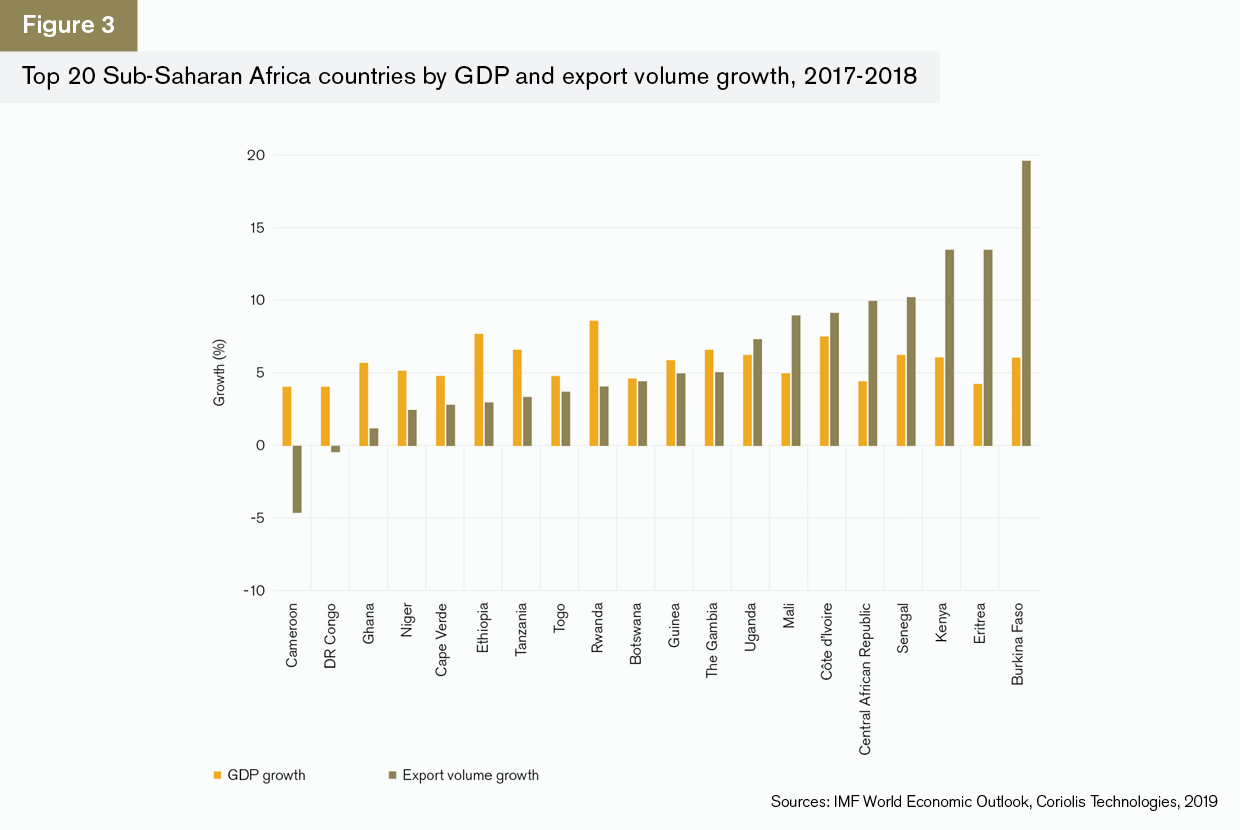

Harding: The non-oil dependent countries in Sub-Saharan Africa have done significantly better than the oil dependent ones in export terms over the last year. South Africa is by far the region’s biggest exporter: in 2018 it exported over US$100bn-worth of goods compared to US$43.4bn exported from Nigeria, the second-largest exporting economy. However, ranked by rates of GDP growth relative to export growth, the economies that have performed best in trade terms are Burkina Faso, Eritrea, Kenya and Senegal (Figure 3):

- Burkina Faso is the 28th-largest exporter in Africa, and its increases in exports can largely be accounted for by a sharp rise in precious metals exports. It has one dominant trade partner in this sector, Switzerland, and the value of these exports to Switzerland have increased at an annualised rate of 1.6% over the past five years to 2018, to a value of US$1.7bn. Although its third-largest sector, fruit and nuts, has grown by 22% annualised over the same period, the value is a fraction of that of precious metals, at US$238mn in 2018.

- Eritrea is the fourth-smallest exporting nation in Africa and while its export growth seems substantial, this is from a value of US$241mn in 2012 to US$381mn in 2018. Grains and machinery and components are strong growth sectors and China, the UAE and Egypt are its major export partners.

- Kenya is the third-largest exporter in Africa with export values worth around US$20.8bn in 2018. Coffee is the country’s major export commodity with a value of US$1.6bn in 2018. Exports have grown at an annualised rate of 1% over the past five years. Its exports of live trees and plants have grown at an annualised rate of nearly 3.5% and exports of ores and slag by a significant 89%, suggesting a major new route for this type of trade has opened up.

Senegal is the fourth-largest exporter in Africa and interestingly, its intra-African trade is the strongest. For example, its exports to Mali, its biggest trading partner, have grown at an annualised rate of over 14%, while exports to Côte d’Ivoire have grown by 16% and to Sierra Leone by 51%. While trade with Côte d’Ivoire and Sierra Leone is still relatively small, hence the rapid growth rates, this nevertheless suggests strong emerging partnerships between these countries.

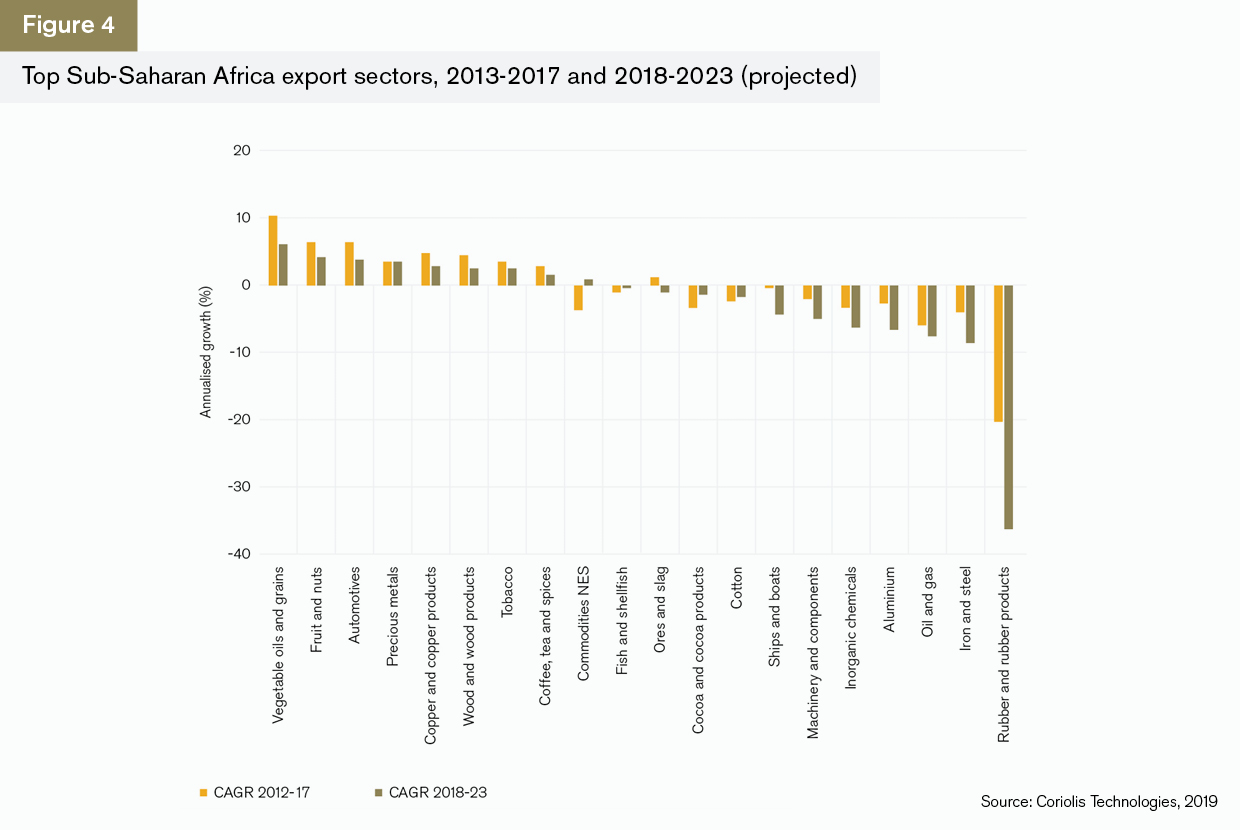

The fastest-growing export sectors over the last five years have been vegetable oils and grains, fruit and nuts, and automotives. Growth in each of these sectors is expected to slow in the coming years but is still positive. Across the hard commodities, the values of oil and gas, iron and steel, aluminium and rubber are set to fall, suggesting that the region will be caught in the slipstream of broader increased tariffs on these sectors imposed by the US as part of the current trade tensions.

This highlights an important point: Africa is an emerging market, and this is perhaps more important than the fact that it is dependent on commodities for its exports. There is a huge amount of potential for growth because it has a young and motivated population and policies that are beginning to focus on the importance of driving this growth through intra-regional trade. But while pan-African infrastructure development remains patchy, and there are trade tensions between the two biggest trading nations globally, Africa will continue to face challenges in terms of driving its exports.

One country that appears to be breaking loose from its dependency on commodities is Ethiopia. While its top sector exports are dominated by soft commodities and precious metals, since 2013 its exports of machinery and components have grown by over 16% annually, its exports of footwear by 14% and its exports of electrical products and equipment by nearly 10%. Its largest African trading partner is Somalia, and although China is also an important partner, Ethiopia’s exports to China have slowed slightly since 2014.

GTR: Is there any evidence that Sub-Saharan Africa is reducing its dependence on commodities?

Harding: Sub-Saharan Africa is a resource-rich region and as a result its trade is always going to be focused in the commodity sectors. There is an opportunity for the region to grow other sectors, such as services and manufacturing, but at present, this is to a very large extent an aspiration rather than evident in the data.

We’ve already talked about the reliance of trade values on the oil price. The correlation between the region’s export values and, say, the coffee price, is substantially lower at 35%, but the profile of the region’s top 20 sectors and how they are likely to grow still suggests heavy dependency on commodities generally and soft commodities in particular (Figure 4).

GTR: Are there any sectors that look like they are growing particularly quickly?

Harding: It’s worth looking at imports to see where growth and development is likely to emerge. This is because Sub-Saharan Africa’s imports tell a story about how the region’s demand patterns are changing.

Figure 5 focuses on the imports that are related to infrastructure development and welfare. Although they are not the largest imports into the region, they do give an indication of where infrastructure development is heading. Ahead of the rest, imports for railway infrastructure have grown by 9.4% annually since 2012 and are set to continue to grow rapidly at an average of 7.1% to 2023. This represents some US$2.1bn of imports by 2023 and although this is still outside of the top 20 import sectors, it indicates that the region’s rail infrastructures are receiving considerable investment.

Of more interest, perhaps, is the alternative infrastructure that is emerging around electronics and computing. Machinery and components, imports of which include computers and data storage, is Africa’s largest import sector after mineral fuels and is expected to reach a value of around US$48bn by 2023. Similarly, electrical machinery is the fourth-largest import sector and is also expected to grow to a value of approximately US$40bn by 2023. These are sectors which improve communication and enable moves towards a stronger manufacturing base.

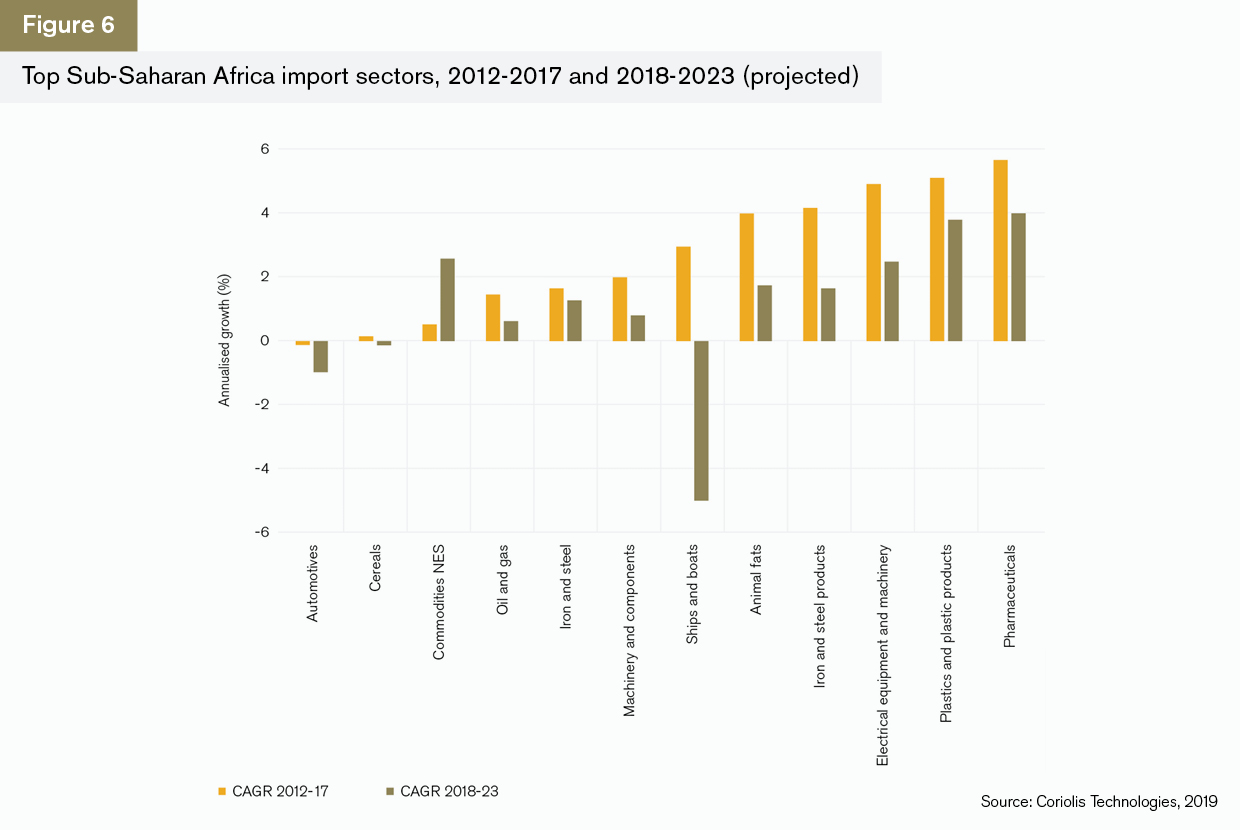

In terms of import growth (Figure 6), the only sector that looks to be in decline is ships and boats. This could be because the region is building intra-regional infrastructure using railways rather than any material decline in the ships and boats sector itself.

GTR: How substantial is intra-African trade? What are the challenges in driving trade growth within the continent?

Harding: Any analysis of intra-African trade is bound to be based on assumptions and estimates. There is a large amount of hidden trade in Africa: many countries simply do not report their data, or do not report it regularly enough to be able to assess accurately how much trade there is between countries within the continent. As mentioned, intra-African trade is estimated to be worth around US$170bn and this ties in with estimates from the Coriolis dataset for goods trade, which indicate that intra-African exports were worth around US$71.9bn in 2018 and imports around US$65.1bn. This is slightly lower than the Afreximbank estimate but excludes services and informal trade.

It is this informal trade that is the problem in measuring trade between African countries. African trade with ‘commodities not elsewhere specified’, which is a generic United Nations catch-all, was over US$14bn in 2018, and trade with ‘areas not elsewhere specified’, a similar UN catch-all for countries, was nearly US$1bn.

However, it has to be the case that if the continent can build its intra-regional trade, then the consequences for economic development led indigenously will be substantially improved. The immediate challenge, then, is to improve the data that is available for understanding where the trade gaps are and how they can be plugged with appropriate technologies and infrastructures.

That said, there is sufficient data to show that intra-African trade is important as a feature of the trade landscape in the region. For example, Coriolis estimates that exports between Sub-Saharan African countries were 21% of the region’s total exports in 2018, up from 19% in 2012. Intra-regional imports as a proportion of all trade are slightly lower at just under 19% in 2018, up from 17.6% in 2012.

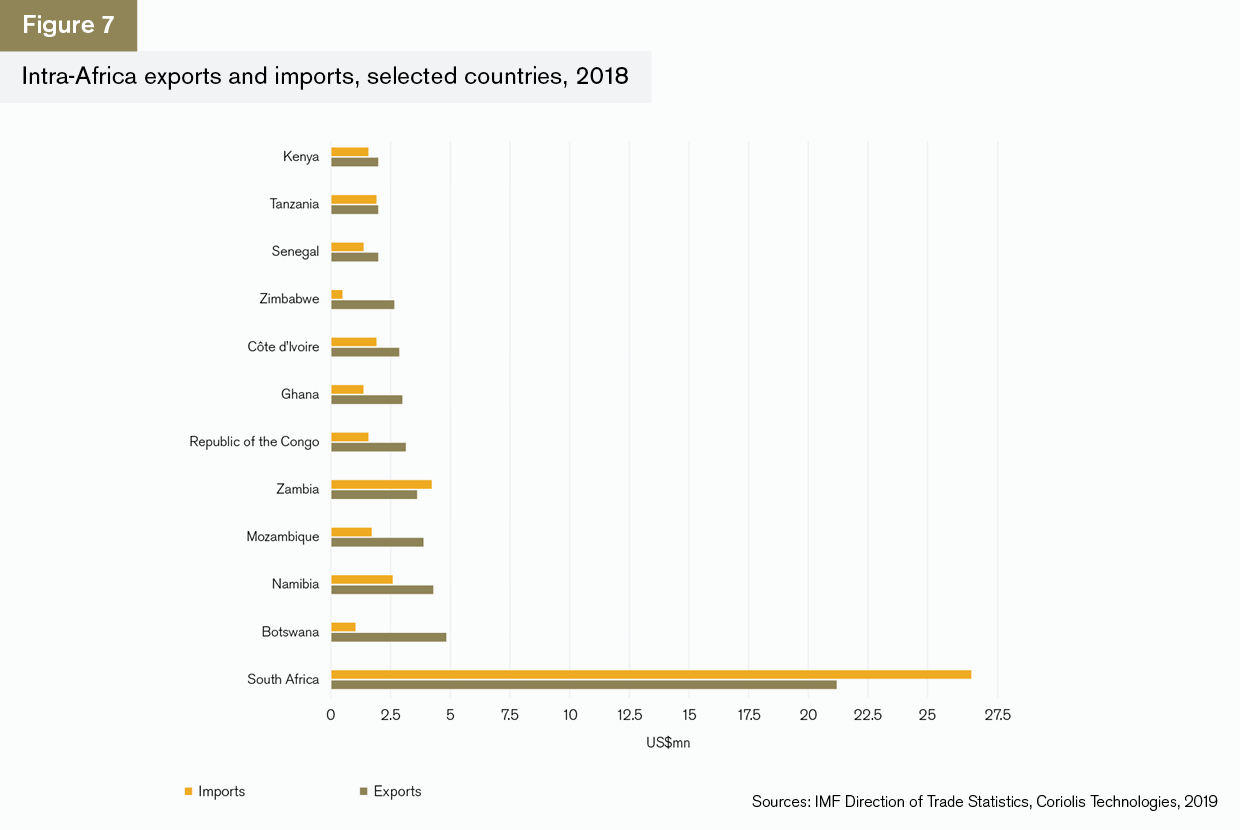

South Africa is the continent’s largest country in terms of imports and exports by a long way with values in 2018 of US$21.2bn in exports and US$26.8bn in imports (Figure 7). Interestingly, it has a trade deficit with other countries in the region. The only other country with a significant trade deficit is Zambia.

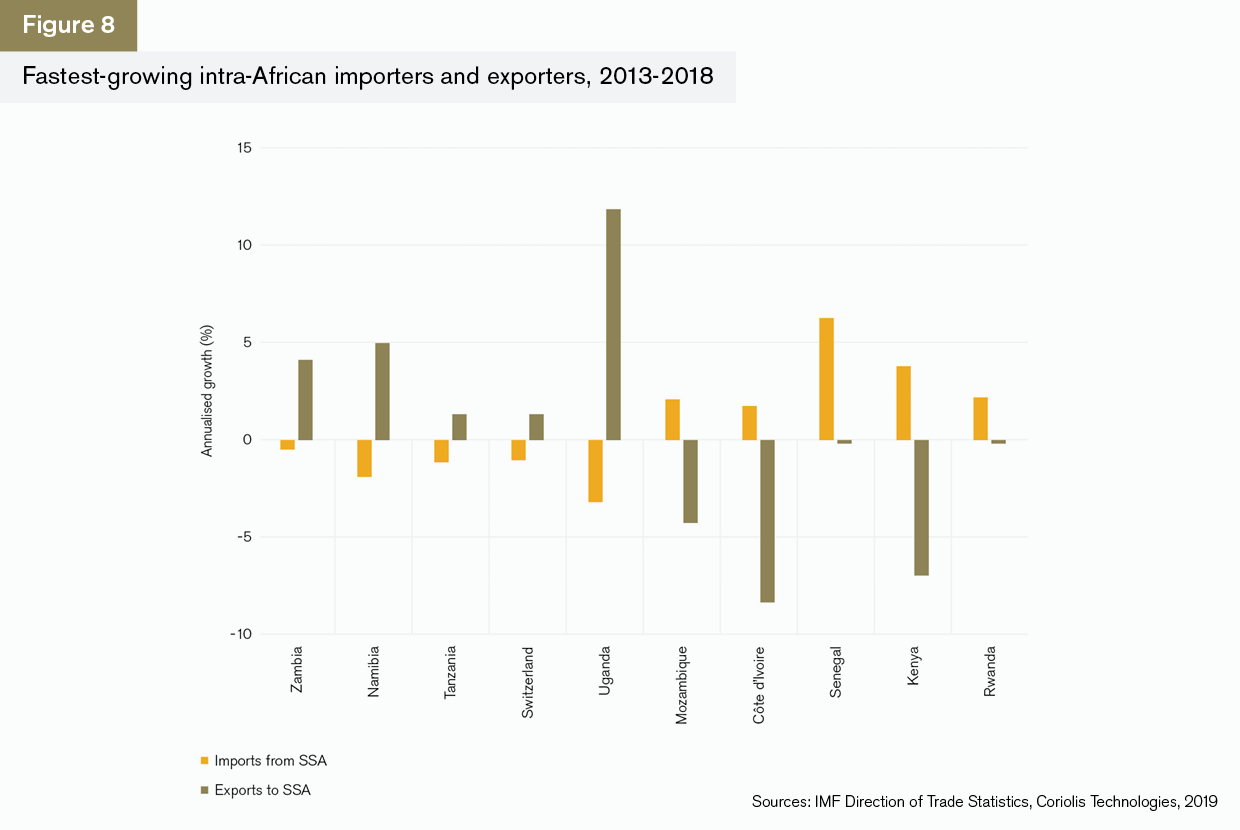

The countries whose regional imports have grown the most tend to be less dependent on hard commodities (except precious metals) and more likely to be trading food-related products (Figure 8). For example, Kenya’s imports from the region have grown at an annualised rate of 3.8% since 2013. Kenya imports predominantly cereals, which have increased by more than 11% annually over the same period. This trend applies to exports as well – Uganda’s exports to the region have grown at 11.8% annually. Its largest trading partners are DR Congo, Kenya, Rwanda and South Sudan, and its principal products are fish, coffee and cereals.

All of this, along with the increase in fertiliser imports projected for the next five years (as seen previously in Figure 5) suggests that Africa is beginning, albeit slowly, to focus its intra-African trade around supplying its needs for food. This is a positive development because it ensures the sustainability of growth rather than reliance on trade with larger partners from outside the region. The numbers are small, and the picture is incomplete because data reporting is poor, but even so, this may be the beginning of an encouraging pattern.

GTR: How is China’s Belt and Road Initiative affecting Africa?

Harding: There is no doubt that the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) offers Africa an opportunity to develop its intra-regional infrastructure. However, there have been concerns about the levels of debt that are involved with engaging fully in the BRI as countries like Sri Lanka and Pakistan have found themselves in difficulties because of heavy investments in their ports. However, Ethiopia’s growth has been driven by substantial investment from China as well as a strong trading relationship; in fact the outcome of the BRI for Africa is likely to be determined by the underlying products that China can trade rather than the transport infrastructure that China can develop to enhance its goals of rebuilding the ancient Silk Road.

China’s BRI strategy is built on the need for critical supply chains. These include access to energy, ports and routes through the Suez Canal as well as the Gulf. Africa was not initially central to the strategy, but it has become more important as the initiative has developed, first, because Africa is an important end-user of its goods, and second, because it plays an important role in energy supply and transport access through Suez.

So far, only five countries within Africa have formally agreed to take part in the BRI: Nigeria, Ethiopia, Kenya, Djibouti and Sudan. Nigeria and Sudan are oil-rich nations, Ethiopia and Kenya represent key agricultural and manufacturing supply chain partners, and Djibouti is increasingly important as a port connecting Ethiopia and Sudan.

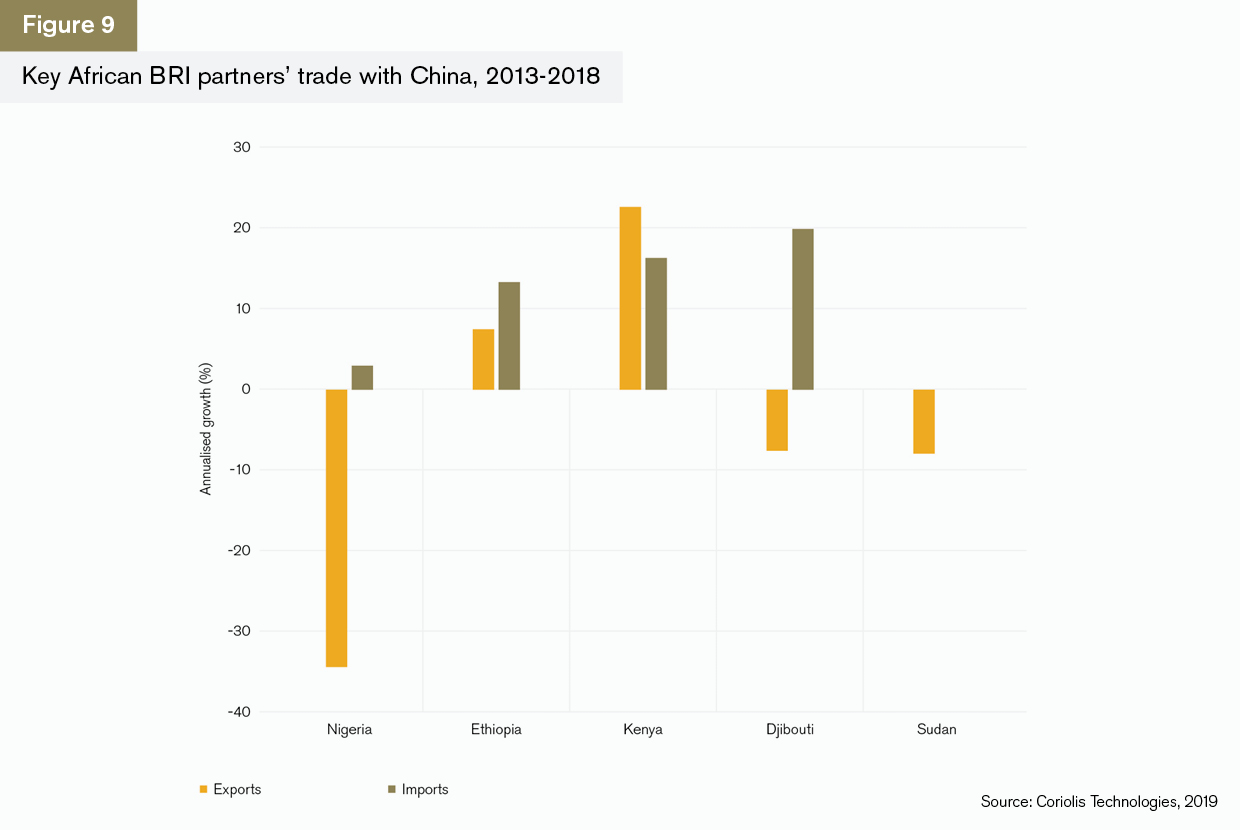

China’s role as a key trading partner has been growing for a number of years against a backdrop of declining trade between Africa and both the US and Europe. The BRI is likely to increase this reliance on Chinese imports, and the rates of growth over the last five years in imports are not matched by substantial increases in exports (Figure 9). Each of the five African BRI partners has a trade deficit with China and, in 2018, the deficit amounted to US$30bn, with imports from China to all five worth a total of US$32.6bn and exports to China worth a mere US$2.6bn. Exports to China from Nigeria, Djibouti and Sudan have declined over the last five years, reinforcing the view that the BRI relationship is strategic rather than economic as such. The drop in oil prices between 2013 and 2016 influenced this decline, of course, since the majority of exports from Nigeria and Sudan in particular are oil and gas.

However, imports from China into Djibouti, Ethiopia and Kenya have grown significantly. Ethiopia is well-established as a part of the Chinese electronics and machinery and components supply chains, while Kenya and Djibouti are building infrastructure projects led by Chinese investment.

The BRI initiative has scope to be an infrastructure boost to the African economy but it is likely to be dominated by partners on Africa’s east coast in the short term as this is where China’s priorities lie. If estimates are correct, then the BRI could boost trade in these economies by as much as US$192m. US investments in and trade with Africa have dropped by over 10% a year since the global financial crisis and the approach of the US towards Africa has shifted markedly since 2016. Engagement with China provides an alternative source of both investment and economic growth for Africa and, if carefully managed, can arguably be beneficial for the region.

However, there are downside risks to the involvement of China: Chinese engagement tends to come with Chinese businesses and workers. Levels of debt could be high, and it could well substitute one form of dependency for another. The jury is still out on the exact benefits for Africa, but what is key is the effective management of the process.

GTR: Will the Africa Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) make a real difference to the continent? Are there any sectors or countries that will benefit in particular?

Harding: The AfCFTA is an agreement that, as this publication goes to press, has been ratified by more than 22 African countries – the number required to bring it into law. It will be the world’s largest FTA since the WTO. Africa’s many regional trading blocs have had some success but because there are many of them, and because some countries are members of more than one bloc, they have not provided the consistency across the continent that is needed if it is to gain the economies of scale from connecting its economies together. AfCFTA covers every country in Africa, including the North African economies of Algeria, Libya, Egypt, Morocco and Tunisia.

The combined export value of the countries included in the AfCFTA was US$590bn in 2018. Many of the economies within the region are small and most are substantially underdeveloped. However, the FTA does provide scope for boosting intra-African trade. The project at the moment looks as though it will go beyond a free trade area to agreements on services, intellectual property, investment and competition policy. There is also talk of agreements around e-commerce. As such, it represents a huge opportunity to streamline and improve standards and transparency.

The challenge for the continent, however, is that it will still be heavily reliant on imports of goods and services in the short to medium term while its exports, even between its members, will be predominantly focused on foodstuffs. This is not a bad thing, but it is a concern if the embryonic manufacturing sector cannot be developed to create indigenous supply chains. This will rely on balancing outside investments, largely from China, with stimulus packages to support small and medium-sized businesses grow through sustainable exports.

There is a long way to go before the AfCFTA is fully implemented, and much is still being discussed. But given the role of China in Africa, it is important that the continent builds on its scalability to be able to have its own voice.

GTR: Access to trade finance has proved difficult for Sub-Saharan Africa in the past few years. Does FDI, and specifically Chinese investment, offer an alternative?

Harding: Trade across Sub-Saharan Africa has declined over the past five years, largely because of the drop in oil prices, but also because foreign direct investment (FDI), largely led by large US businesses, has also fallen back. Some of this is because of the tightening of global KYC and AML regulations since 2014, as well as the decline in correspondent banking, which has resulted in a withdrawal of the largest banks from the region.

This puts the region’s exporters, especially those focused on intra-African trade, in a difficult place. Afreximbank has opened up US$800m in credit lines for these businesses to be delivered through 55 banks across the region, but it will take a while for this to come into effect and impact trade growth.

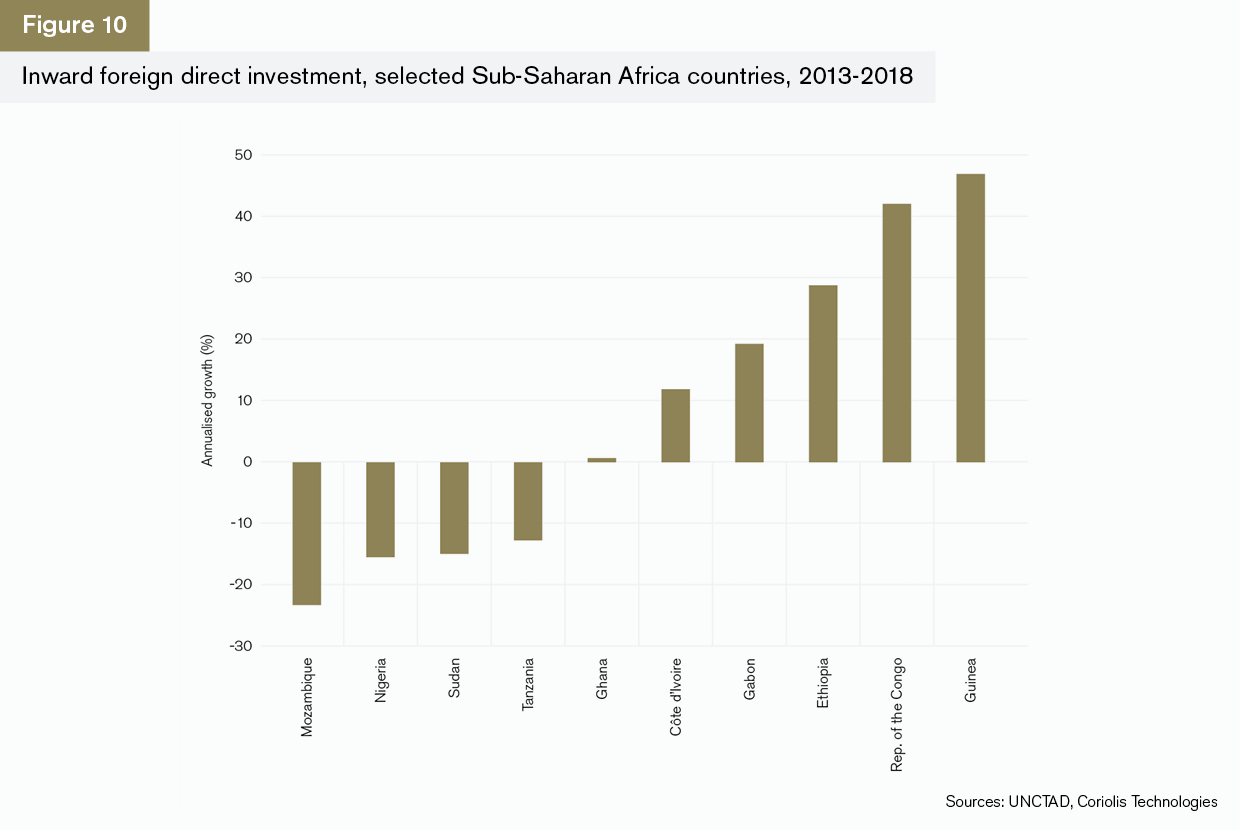

The top 10 countries for FDI are those which have less dependency on oil (Figure 10). For example, Guinea’s major export sector is fish, and, unlike many African nations, its major export partner is India. Its export trade in ores and slag has been growing substantially, suggesting that it is taking a greater role in some of the waste-side products of infrastructure development. Similarly, the Republic of the Congo’s growth has been driven to a large extent by a peak in exports of ships and boats between 2006 and 2018. As its major trading partner is China, this may well reflect Chinese FDI.

The AML and KYC issues around traditional trade finance in Africa have been well-documented but they leave the region with two problems. The first is how to harness FDI generally in the interests of improving export-led growth from within Africa. China and India are competing in the region for investment but India is not investing on the scale that China is, and, more importantly, does not have the extensive infrastructure and supply chain networks either. This makes China an important player in the longer term.

Second, China’s export credit agency, Sinosure, until recently had not been able to invest in non-Chinese companies. This has changed in the last year, and while in the near term the target of Sinosure is more likely to be large US corporates which are unable to get funding from the Export-Import Bank of the US, there is scope for BRI projects to be funded more substantially through this type of investment, especially in countries which are excluded from the US-led system because of the fear of non-compliance.

GTR: Can Sub-Saharan Africa overcome its reputation to attract more investment and grow?

Harding: There are indeed signs that the region’s policy makers, multilateral banks and established players, such as Afreximbank, are determined to create a more coherent and cross-regional approach to trade that will overcome Africa’s reputation for instability and corruption in particular.

At an individual country level, the latest Coriolis political risk survey suggests that for many African nations, risks associated with regime and corruption have increased. There is evidence, for example, of rising repression and human rights abuses in some countries which undermine the constructive work being done through the free trade areas to promote economic growth. Alongside the economic uncertainties from the prospect of a global trade war, and the impact that that has on sustained investment around the world, it would be difficult to suggest that there are not tough times ahead.

However, there are reasons to be optimistic: trade outside of the traditional hard commodity sectors is strong: some countries, particularly Kenya and Ethiopia are growing quickly, the Belt and Road Initiative offers a means for attracting inward infrastructure investment, and there is evidence that intra-regional trade outside of oil and gas is growing.

The biggest hope rests in the capacity of policy makers involved with the AfCFTA to pull together and create a region with coherent trade rules and standards, common compliance and mechanisms for investments and policies that override the uncertainty that is endemic to policy in individual nations within the region. There is a common perception that African growth has to be substantial in the next five years. It will be trade that helps deliver that.