Banks, trading houses and insurers involved in seaborne trade are facing more pressure over sanctions than ever before, thanks to rising international tensions, new guidance from regulators and an ever-growing list of prohibited vessels. John Basquill examines how firms are turning to maritime analytics technology to ensure they stay on the right side of the law.

A long-awaited advisory from the US’ Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) has changed the rules of the game for maritime trade. The sanctions regulator – which sits within the Department of the Treasury and has the power to hand out multi-billion dollar fines to entities anywhere in the world – published the new guidance in late May 2020.

Its content was not a surprise, having been trialled by officials and previewed by GTR in early March. With around 90% of global trade believed to involve seaborne transportation, OFAC says it is “critical” firms increase the level of due diligence carried out across their entire maritime supply chains to minimise the risk of exposure to illicit activity.

The advisory singles out the energy and metals sectors as particularly high risk, giving the examples of petroleum from Iran or coal from North Korea as commodities that could trigger sanctions. OFAC also issues sector-specific guidance to financial institutions, insurers, shipping companies, port authorities and even vessel captains.

Its impact is expected to be significant. OFAC identifies several activities that could be indicative of illicit activity, such as ship-to-ship transfers – where cargo is moved from one vessel to another at sea, a technique it says is “frequently used to evade sanctions” – as well as voyage irregularities, tampering with vessel identification measures, and manipulating location transmissions.

Those demands suggest firms are expected to go beyond simply checking that vessels or their owners are not on sanctions registers. They will now have to monitor and scrutinise the behaviour of individual ships themselves.

“The message is loud and clear,” says Simon Ring, global head of financial markets compliance at Pole Star. “The bar has been raised. You’re now looking at a far more comprehensive range of screening and analytics tools before you engage with a vessel.”

Pole Star, a London-based technology firm that tracks and analyses data associated with a ship’s behaviour, was among the firms consulted by OFAC in the two years leading up to the publication of its advisory in May.

“Basic screening provides nowhere near the level of detail you need now. It’s about all of the parts around that, such as the ship’s movements, its history, its trading patterns and its reporting,” Ring tells GTR. “That’s where the US government has now had two years of education: when ships can be seen to ‘go dark’.”

Going beyond AIS

Monitoring a ship’s movements remains an important part of behavioural analysis, which is essential for marine security and safety. Much of that relies on the automatic identification systems (AIS) that cargo ships and tankers are required to have on board.

Originally developed as a tool to avoid collisions, AIS signals are transmitted via satellite to show the location of the ship. Sometimes ships will go dark, meaning those signals are no longer being broadcast or detected. That usually happens inadvertently, for instance in congested waters, but can also be an indicator that the vessel is carrying out some kind of illicit activity.

“The ratio between innocent or lost and deliberate turning off transmissions is probably between 1:10 and 1:20, depending on the area and type of ship,” says Ron Crean, vice-president for commercial at Windward Maritime Analytics, a Tel Aviv-based firm that provides behavioural analysis on ships.

“That means for every 10 or 20 times we see a vessel that isn’t transmitting for a number of hours, one of those would be a ship deliberately turning off transmissions.”

For a bank or oil company attempting to monitor that data, Crean tells GTR that creates a large number of false positives, where compliance staff may need to carry out a manual check of the potential risk involved. It’s a situation that can get “messy”, he says.

Guy Sear, executive director for product management at IHS Markit, agrees banks can struggle to process the large amount of data they collect when managing vessel tracking themselves.

“The volume of data we work with is astronomical,” he tells GTR. “Standardising that into a format to get the intelligence out of it that the regulators are asking for is a major challenge for the banks, and that’s where we see them calling out for help.”

Sear says IHS Markit – which offers commercial analytics services but is also designated by the UN as a source of vessel information – combines basic factual data about a ship with contextual data, such as open source information about ports around the world.

Combining that with tracking AIS signals, the company can see where a ship has been and whether it has encountered other vessels, giving the opportunity to spot suspicious port calls or ship-to-ship transfers. Also crucial is data on a vessel’s ultimate owner.

On top of that comes machine learning. Sear says “algorithmic technology can derive behavioural patterns from that data, taking the information all the way up to form an actionable piece of intelligence”.

In Pole Star’s case, Ring says technology “is really good at finding the needles in a haystack”. Single fields of data covering various aspects of a ship’s characteristics – such as its trading patterns, ownership, movements and flag registration – are combined to generate an audit trail.

“It doesn’t displace a compliance team or programme, but points them in the direction of where they need to be focusing their time and energy, rather than looking across swathes of transactions and flows,” he tells GTR. In the case of large banks and trading companies, the sheer volumes of transactions handled means that “can be impossible”.

If a vessel has gone dark, combining location data from different sources – known as hybrid tracking – is important, Ring says. If it is no longer transmitting AIS signals of any kind, that could suggest transponders have been switched off deliberately.

At that point, firms can examine the last known location of the ship, then its location once AIS reporting resumes.

If it was close to a high-risk area, that could be a red flag for illicit activity.

Ring says another factor could be whether there is any indication that the vessel has onboarded or unloaded any cargo during that time, visible if it is sitting higher or lower in the water. “That’s really geared towards ship-to-ship transfers,” he says.

Spotting ship-to-ship transfers

In some cases, spotting ship-to-ship transfers could be crucial in detecting sanctioned trade. The OFAC advisory says transhipment can conceal the origin or destination of petroleum, coal and other material – “especially at night or in areas determined to be high-risk for sanctions evasion or other illicit activity”.

Data provided by Windward shows that Venezuela – subject to increasingly tough OFAC sanctions since the start of 2019 following escalating tensions with the US – appears to make relatively heavy use of ship-to-ship transfers as well as port calls for its oil imports and exports.

Though it sits on vast oil reserves, Venezuela’s last two operating refineries were closed in early 2020. That has meant it must look outwards for petroleum products, and in sanctioned Iran has found a willing seller. At the same time, Venezuela continues to supply crude oil to Cuba, which has working refineries but low natural reserves.

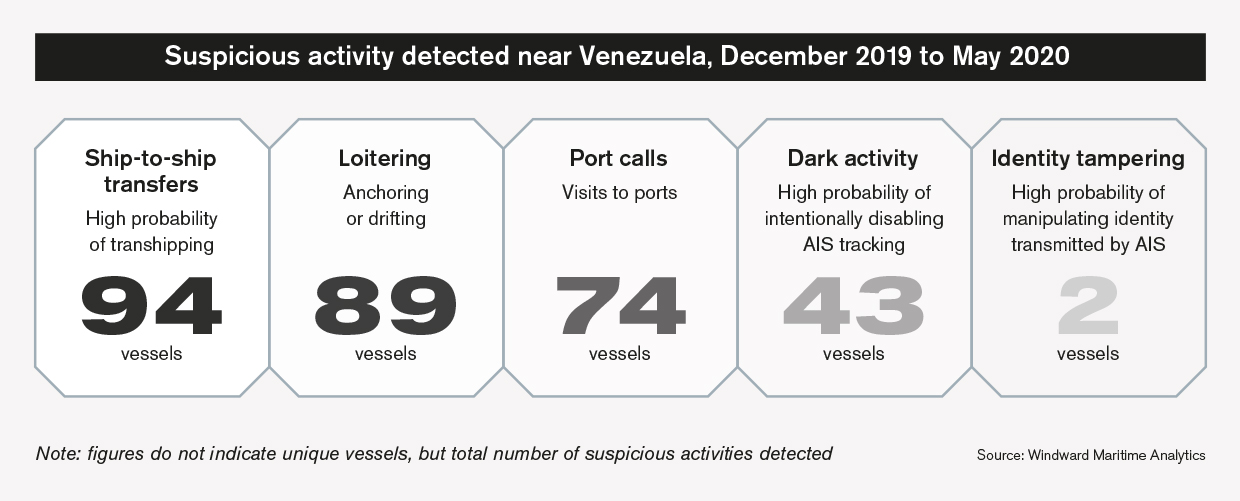

Between December 2019 and May 2020, Windward analysed 180 tankers that appeared to be involved with Venezuelan trade, and therefore potentially at risk of being designated under OFAC’s sanctions regime.

It identified 94 cases of ship-to-ship transfers and 89 cases of loitering, compared to 74 port calls and just 43 examples of ships going dark. Identity tampering was only detected in two cases.

Theoretically, that means a vessel could be transporting oil from Iran to Venezuela, or from Venezuela to Cuba, without ever visiting a port in the South American country. Monitoring AIS transmissions but not carrying out behavioural analysis would likely mean that activity goes completely undetected.

“Where authorities are really looking for improvements is on the illicit transfer at sea of goods and commodities, that can end up in North Korea, Iran, Syria or other risk areas,” Pole Star’s Ring says. “Stationary ships in high-risk locations is the name of the game.”

Windward has previously identified other cases in relation to oil trade involving Iran, where standard sanctions screening and AIS tracking alone would not have flagged up illicit activity.

In a June 2019 case study provided to GTR, the company says a Chinese oil importer asked its bank to open a letter of credit in favour of a Malaysian oil trading firm. The transaction involved a US$140mn purchase of crude oil.

Two rounds of screening by both the applicant and beneficiary banks found no sanctions hits against the exporter, ports involved, cargo itself or any other aspect of the trade.

However, it emerged in October the same year that the ship had met an Iranian oil tanker at sea and was then sitting deeper in the water, suggesting it had taken on new cargo.

Windward says analysis of the ship’s movements would “likely reveal [it] was involved in the dark Iranian crude trade well before this incident”. The ship was found to have entered waters close to Iran’s Kharg Island oil terminal and switched off its AIS transponder, before reappearing and turning around without openly visiting a port.

Early days

Adoption of analytics technology is relatively widespread among protection and indemnity insurance clubs, which provide cover for the vast majority of maritime trade. Among financial institutions, however, IHS Markit’s Sear says there has been “very little adoption”.

“My honest feeling is the tier-one banks have been looking at it, but I wouldn’t say they had fully adopted it,” he says. “It’s more the mid-tier banks that are really looking to get into it, because they realise they can’t scale as well as the tier ones, and so need technology partners to help them.

“A mid-tier European bank that only trades in liquid cargoes might want to be the experts in markets and trading, but not in machine learning and data science. At the same time, they already often sit in slightly higher risk markets anyway, because they have to try and find that edge, so they don’t want to have over-exposure.”

Adoption of the technology appears to be growing in the commodities trading sector. BP Shipping, the maritime arm of one of the world’s largest energy companies, announced in mid-June it had partnered with Windward, with the decision propelled by the OFAC advisory.

Mark Fortnum, BP Shipping’s vice-president for technical and vetting, says the decision had been made over the last year, but that the OFAC advisory is “a game-changer for the maritime and trade ecosystems regarding compliance requirements”.

“Solutions that can increase both quality and efficiency in our sanctions compliance operations are essential across all related business transactions,” he adds.

Looking ahead, it is possible maritime analytics technology could be combined with other data sources to expand its use beyond sanctions compliance. Sear says IHS Markit has been looking into “dual-use cargo screening”, to detect whether goods being shipped may have an illicit purpose.

This involves information from a bill of lading being extracted digitally and analysed against numerous data points from relevant industries, such as chemicals or militarised goods. The system can then provide a warning if the trade relationship is in some way suspicious.

“That warning would be based upon this neural network of goods descriptions and categories, to say whether the trade that the bank is financing could potentially have a militarised or dual-use purpose,” he says.

“That’s really the next step, where regulators like OFAC are beginning to push the banks. It’s not just using technology to look at the vessels, but at the trade and the trading patterns, to begin to flag things like trade-based money laundering.”