Russia’s ambition to grow trade with Africa is already evident in increased capital goods exports. But EU and US sanctions on some Russian companies make doing business with Russia tricky for many African sovereigns, while critics question how the latest drive differs to previous promises to increase trade – which have delivered little. Sarah Rundell reports.

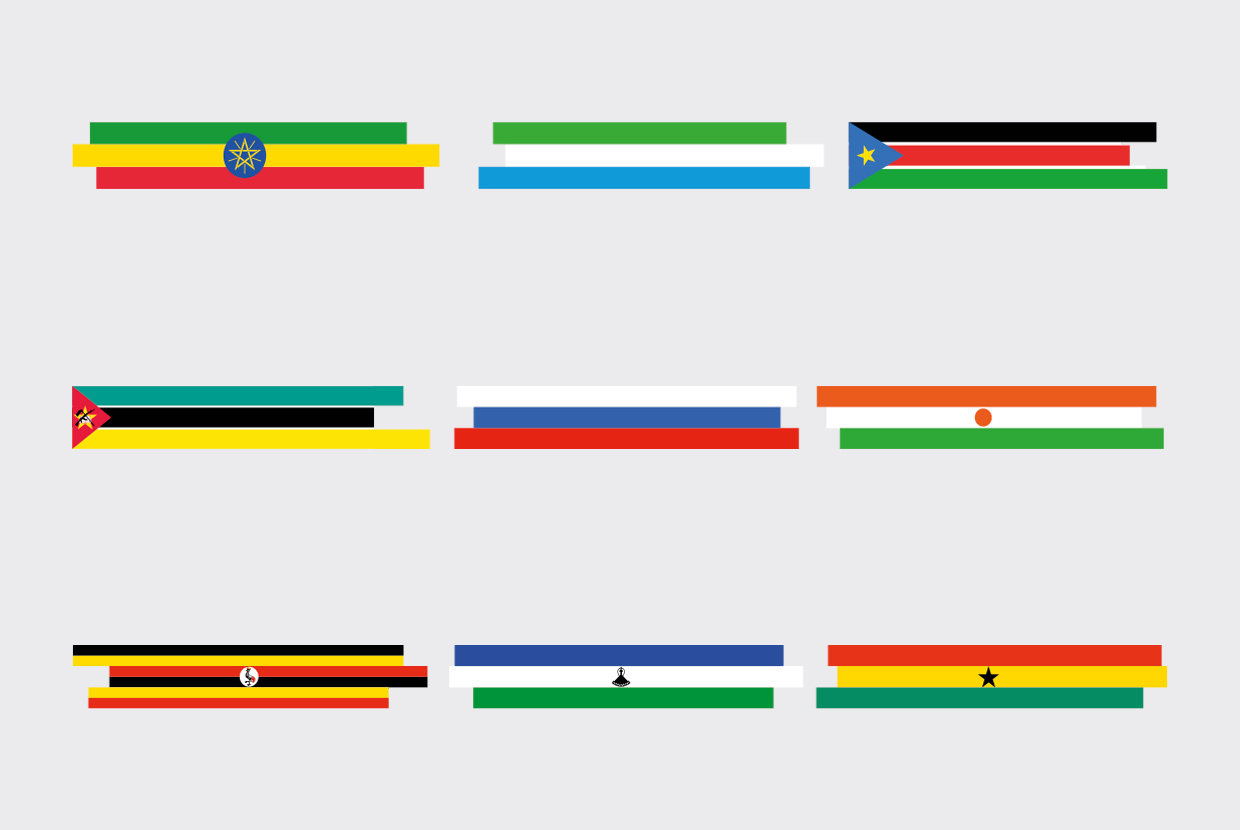

As soon as global travel restrictions are lifted, Russian trade envoys will fulfil plans to visit six fast-growing African countries to ink deals sketched out in agreements made at last year’s inaugural Russia-Africa summit in Sochi. Russia’s desire for new trade partners in Africa is one consequence of US and European Union sanctions, first imposed on Russia in 2014 for its support of separatists in Ukraine and then tightened by the US for interference in its 2016 election. They include travel bans for prominent individuals and prevent access to long-term financing for a clutch of high-profile Russian corporates and banks.

More trade with Africa can’t replace lost access to the capital markets and key Russian companies’ ability to attract long-term investment. But new African partnerships do offer one way to offset frayed traditional relationships. US President Donald Trump’s recent decision to slap sanctions on any firms that work with Russia’s sanctioned state-owned Gazprom to finish Nord Stream 2, the gas pipeline under the Baltic Sea linking Russia and the EU, shows how fraught the standoff has become.

As for building new trade links in Africa, Russia is late out of the starting block. The African Export-Import Bank (Afreximbank) estimates Africa and Russian trade at about US$20bn compared to US-Africa trade at US$61bn, China-Africa trade of roughly US$200bn, and EU-Africa trade of more than US$300bn. Yet Russia, which has a strategic advantage in the energy and defence sectors, is behind the curve in Africa, and is determined to catch up.

Some Russian industries have already boosted capital goods exports to Africa, says Rene Awambeng, global head of client relations at Afreximbank, who estimates the bank has a current Russia-Africa pipeline worth US$5bn. “We are seeing increasing interest on the trade side in key sectors around heavy infrastructure like railways and wagons, energy and oil services including refined products, and fertilisers, as well as softs, like grain.”

Looking ahead, he expects a pick-up in demand for Russian aircraft in a boost for domestic manufacturers like Sukhoi. “There are efforts underway to get Russian aircraft certified by national and regional carriers on the continent,” he says. Elsewhere, a memorandum of understanding between nuclear group Rosatom and the governments of Ethiopia, Rwanda, Egypt and Kenya to establish nuclear power stations also promises future trade links, as do defence ties. Between 2014 and 2018, Africa – excluding Egypt – accounted for 17% of Russia’s major arms exports, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

Afreximbank is also partnering with the Russian Export Centre (REC), the state export support institution, which is now a strategic shareholder in the African bank following its successful subscription to class ‘C’ shares. “We are looking at doing some form of risk sharing with them [REC] on transactions that push Russian trade into Africa, and push Russian products into the continent,” says Awambeng.

Dealing with sanctions

European Union and US sanctions on Russia can present issues for African sovereigns doing business with Russia, even when these countries have no sanctions regime against Russia of their own. Access to finance is a typical example. Multinationals and western banks are wary of working with Russian partners in large deals wherever they are in the world, says Ashley McDermott, a partner in Mayer Brown’s London office. It could affect, for example, the production of liquefied natural gas (LNG) in Mozambique if Russian companies and banks are involved, he suggests. “The involvement of Russian players will make the compliance and sanctions issues on multi-source, multi-billion dollar projects even more complicated for those banks and companies who have to comply with US sanctions, in similar ways to what we saw recently with Nord Stream 2.”

Banks involved in the earlier stages of financing Nord Stream 2 have seen timings and returns pushed out. Russia is now finishing the project alone after Swiss group Allseas, the main contractor that had been laying the pipeline, suspended operations due to Trump’s promise to sanction any firms that work with Gazprom.

Yet it’s important to remember that not all Russian banks and companies are under sanctions. They only apply to specific sectors and target a number of specific Russian energy companies, banks and defence groups. “Nor does every Russian joint venture or deal require finance,” says Petr Molchanov, head of investment banking for Russia and CIS at Renaissance Capital in Moscow.

The most important thing is enhanced know your customer (KYC) and compliance checks to ensure African companies understand the risks of working with blacklisted entities, explains Afreximbank’s Awambeng. “We advise all customers to look at this. It’s not a minefield, the information is out there. It just requires work to ensure due diligence,” he says.

Indeed, even working with sanctioned companies is not a complete no-go, says Genevra Forwood, a partner at White & Case in London and Brussels. “It is more the case that there are specific things you can’t do with these sanctioned companies. You might not be able to, for example, lend money or deal with any new equity they might have issued, so if one of them is setting up a joint venture, this could raise issues. It is about looking at the structure though which the investment is happening and the specific involvement

of the sanctioned Russian entity.”

That said, Forwood points out there is always the possibility that the EU and UK impose further sanctions on Russia, such as so-called Magnitsky sanctions. Based on US legislation introduced in 2012, Magnitsky-style reforms would allow sanctions and asset-freezing measures against individuals rather than institutions or whole industries. “This could lead to a deeper focus on specific individuals and their interests across a number of sectors,” she says.

Trade finance needs

Many banks are beefing up their trade finance offering. VTB Bank, subject to US sanctions since 2014 (other jurisdictions have since added the bank to their sanctions list) is actively developing its trade and export finance solutions in response to increased interest in Africa from clients and counterparty banks, says Igor Ostreyko, the bank’s managing director of trade and export finance. He predicts that most growth will be in agricultural exports like machinery and fertiliser. “We already have experience in trade finance business flows by following our clients into various countries in North and Sub-Saharan Africa,” he says, adding that the number and volume of transactions to African countries in 2019 increased significantly, mostly from commodities, food and equipment delivery sectors.

Products the bank is planning to roll out include facilities to cover non-payment risk, providing financing options for buyers, and helping clients optimise their cashflow. “We could confirm and discount letters of credit (LC) issued by local African banks, allowing Russian clients to avoid the risk of non-payment by African counterparties. We are also looking into supply chain financing for Russian and African businesses,” he says. “The main issues our clients encounter are risks around receiving payments on deliveries, a lack of financing for African trade deals and challenges in streamlining efficient relationships with African counterparties.”

LC financing is a central tenet in VTB and Afreximbank’s growing relationship. In 2019, VTB signed a Trade Confirmation Guarantee Programme with Afreximbank which includes a facility whereby Afreximbank confirms LCs issued by African banks on behalf of these banks’ importer clients. “LC financing will be primarily interesting to Russian suppliers willing to expand their business volumes and make Africa one of their core markets,” says Awambeng.

Elsewhere, experts report “good overall support” amongst Russian banks for their domestic exporters looking to Africa. Russian banks, used to volatility and a tough business climate, aren’t put off by African risk, says Molchanov. He adds that Russia’s state-controlled banks are also sitting on healthy amounts of liquidity. “Russia’s banking sector has been cleaned and de-risked by the central bank, which revoked a number of licences,” he says.

The biggest challenge from an African perspective seems to be that few Russian banks are active on the continent. “Russian banks are supportive of their exporters, but they don’t know the continent well and are working with us to build their knowledge,” says Afreximbank’s Awambeng.

Gap in the market

Russia is seeking to increase trade flows with Africa at a time when China is less active. China’s trade with Africa grew at a slower rate in 2019 compared to previous years, with two-way trade increasing by just 2.2% in 2019 to US$208.7bn, compared with a 20% rise the previous year, according to official figures from China’s General Administration of Customs. Elsewhere, many western banks and businesses have stepped back from Africa because of KYC. “The fact UK and US businesses are having to comply with ever increasing anti-corruption and procurement rules is an opportunity the Russians will take advantage of in Africa,” says McDermott at Mayer Brown. “Russian exporters and traders can be nimble in this respect.”

But it’s far from an open goal. Foreign state-run entities like the US’ newly established International Development Finance Corporation, which recently promised US$5bn to Ethiopia with a remit to help Washington’s foreign policy aims, including countering the influence of China – and Russia – in Africa, are actively supporting their own domestic exporters. “Africa is free to choose its commercial partners on free and fair terms,” says Afreximbank’s Awambeng. “We only provide the platform. Companies have to deal with who they want to deal with.”

Russia’s motivation

Some experts also observe that trade may not be centre stage for Russia’s ambitions in Africa. Rather, its interest in the continent could be borne more from a desire to increase its sphere of influence. It’s a suspicion that has roots in previous eras of co-operation, such as a 2009 pledge by Gazprom to invest at least US$2.5bn in a joint venture with Nigeria’s state-owned oil company Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC) called Nigaz, which was set up to explore and develop the country’s vast gas reserves. Despite pledges that the two would become “major energy partners”, the agreement floundered with critics saying Russia’s real motivation was to stop Nigeria being an alternative source of supply to the European gas market.

Old memories have been awakened by plans reached in Sochi last year for another joint venture, this time in the refining sector between the NNPC and Russia’s Lukoil. “There is an underlying perception in quite a few African countries that Russian interest in Africa is not so much around commercialising projects as about geopolitical influence. The test will be which of these long list of investment commitments are realised in the long term,” says Lai Yahaya, senior policy advisor to the African Union High Representative for Infrastructure Development in Africa.

Yahaya also queries whether Russia has the financial firepower and balance sheet to invest heavily in Africa, particularly given Africa’s main priority is large-scale infrastructure investment. “The question after Sochi is whether the Russians actually have the finances to commit to significant investment like China,” he says.