Funds in Asian trade finance are becoming increasingly visible, as banks scale back their lending. Finbarr Bermingham speaks to three funds making hay in the banks’ absence.

The logic is simple, if a tad reductive: a tough time for banks equals a good time for non-banks, and over the past couple of years in Asia, banks have had a torrid time. The ICC Banking Commission’s Trade Survey 2016 showed that globally, Swift trade finance volume fell for the fifth year in a row. The overall drop of 5% was steeper than previous years. While Asia’s drop of 1.08% was the lowest of the world’s regions, it was a decline nonetheless.

Macroeconomic conditions certainly contributed to this drop: 2016 was the sixth year in a row that global trade growth was lower than GDP growth. In 2015, the monetary value of the world’s merchandise exports fell by 14%. Data for 2017 looks slightly more promising (the CPB World Trade Monitor released in May showed that the volume of world trade increased by 1.5% in March, having decreased by 0.8% in February), but there are plenty of other causes for concern among banks in Asia.

Due to the cost of compliance and regulation, even the liquid western banks are retrenching from Asia. Their risk appetite has diminished, exemplified by a Dealogic statistic that shows that of the top 20 banks financing infrastructure projects in the last year, only one was not Asian (Crédit Agricole). Coalition’s data on transaction banking shows that overall, trade finance volumes were down 9% in Asia last year, while its investment banking tables show that western banks hold only 19% of the Asian banking wallet, compared with 24% two years ago.

All of these factors point to a sector on the wane – and there may be worse to come. Ernst & Young’s Bank Relevance Index shows that banks are more vulnerable to alternative financiers such as online banks, peer-to-peer lenders and investment funds in Asia than they are elsewhere in the world. The report reads: “Asian banks are more vulnerable to decreasing relevance, as demonstrated by low scores in Indonesia (66.9), China (69.5) and India (71.1) [100 represents complete “relevance” for banks], likely due to the prevalence of mobile and non-traditional banking options and the evolving ‘unbanked’ population.”

“There’s a global trend towards non-bank financiers, partly to do with Basel III, and one thing guaranteed is that Basel is going to get harder. There are opportunities for more nimble providers,” Ilkka Tales, managing director for Asia Pacific at Greensill Capital, tells GTR. Greensill offers supply chain financing solutions to clients, providing the funding on its own balance sheet, and then subordinating some of the debt to funds, such as pension and superannuation funds – parts of the financial sector that are becoming more prevalent in Asian trade.

Research shows that large Asian companies are more likely to use bank finance than any other regional corporations. Thus, the amount of fund involvement is low in relative terms, but growing. Anecdotally, you hear of the funds’ presence in the market from time to time. One senior banker at Citi tells GTR wistfully that if they don’t see funds on deals, it’s because they can only dream of operating in the same price bracket as them. They’re often portrayed as shadowy, fly-by-night outfits that shun publicity – but some funds are determined to buck the trend. They are speaking to the press and becoming more visible at industry events. We tracked down three such players who were happy to share their stories about how they are capitalising on the changing dynamic in trade finance.

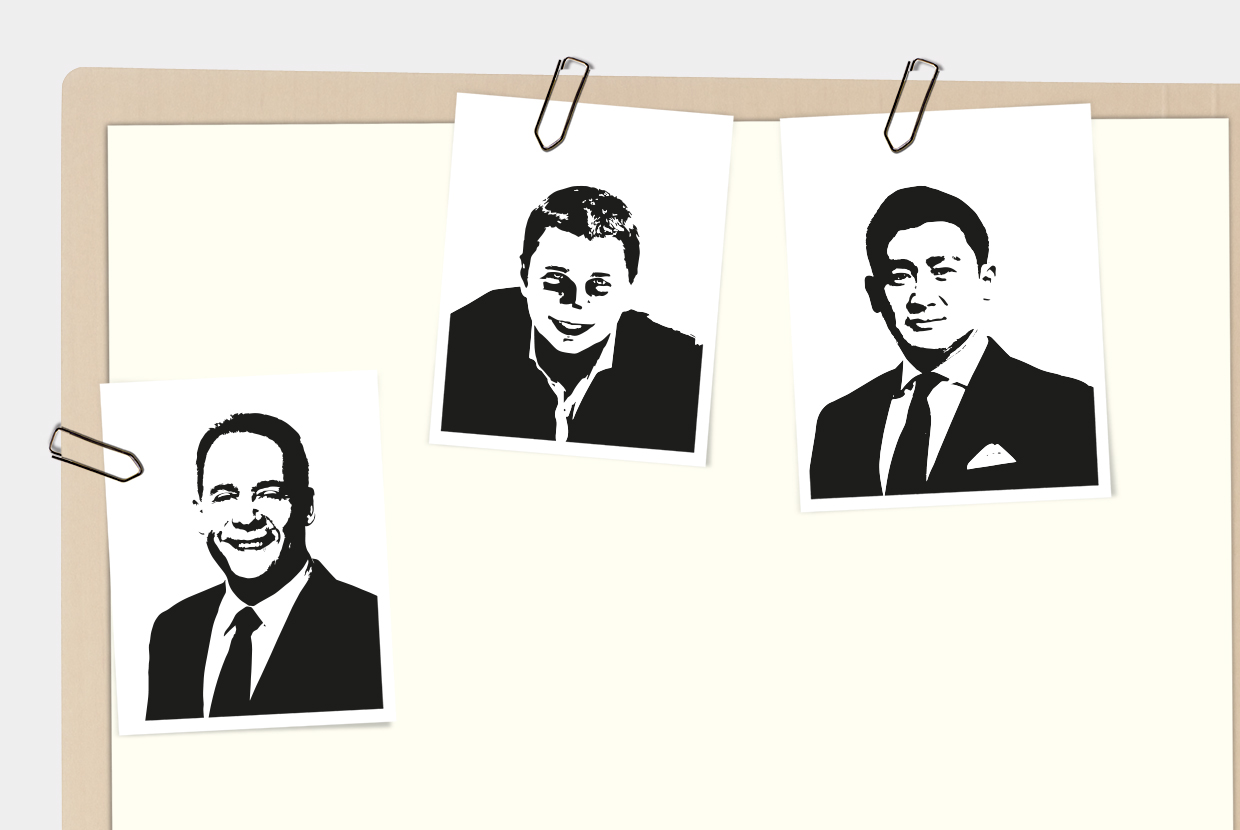

Teall Edds, OCP Asia

OCP Capital is not a trade finance fund per se, but the extent to which it has dipped its toes in these waters, and its reasons for doing this, demonstrate another way in which funds are muscling in on bank territory. The fund was established in 2009 by Stu Wilson and Teall Edds, both of whom have substantial experience in Asian markets.

Over the past few years, the evaporating risk appetite of western banks has left the door open for OCP to fund metals, which have buoyant demand but have been struck off the banks’ funding lists due to systematic risk profiling.

“We’ve invested in lithium and cobalt over the last 18 months because, overall, the banks reacted negatively to the global commodities sell-off. Commodities have been a difficult place to be over the last four or five years. However, within that you have the counter-cycles of individual businesses. While coal and oil prices were coming off, you saw growth moving towards cleaner energy solutions. Combine that with the electronics sector growth, notably smartphone technology and it gives rise to cobalt and lithium demand,” Edds tells GTR.

He adds: “You have certain subsectors not getting serviced because banks are constrained in their ability to take additional commodities exposure. You have companies coming to us and saying that their underlying commodity has robust fundamentals and that, structurally, there’s not enough of what they are producing in the world.

“The main thing when you come to an investor like us, you’re not just going to presume that our exposure to commodities is closed. Banks tend to hit their concentration limits, which are set at arbitrary levels – they say ‘no more of this’. We tend to say they’ve thrown the baby out with the bathwater.”

Interestingly, the lack of trade finance lending means that there are a lot more unencumbered assets in Asia than there were five years ago. Companies have more real estate or premises to borrow against, and that has created another avenue for OCP to exploit – again, capitalising from the decline in mainstream trade finance. One sector in particular which has been bountiful has been maritime infrastructure development in Indonesia.

“There’s a policy tailwind with President Jokowi saying he wants to take more advantage of its maritime capacity to open its manufacturing and commodity capacity. Port capacity has been a huge bottleneck. Land transport too, but maritime has underperformed in servicing commodities and supporting manufacturers.”

He adds: “We’re seeing opportunities both for domestic infrastructure as well as international. We’re not providing project finance, to be clear. Companies can still find senior secured lending. But a lot of businesses want to buy logistics capacity. They need to provide the equity portion of that investment. The reality is a lot of businesses have built up incredible wealth in assets outside that sector, the families [that run the businesses] diversify themselves across companies. You can lend against their other businesses so they can invest their equity capital in port infrastructure.”

Francois Dotta, EFA Group

When people talk about trade finance funds in Asia, EFA Group is normally quick to come up in the conversation. It still defines itself as boutique, but if you talk to other non-bank lenders in the space, they’re often name-checked as “one of the big boys”. Francois Dotta is the head of origination at the company. He’s happy to talk about the fund’s growth.

“Last year we did more than US$2bn of financing of trade flows, which is a drop in the ocean compared to global trade finance volume, but it’s still a meaningful amount,” he tells GTR. But perhaps the biggest indicator of a shift towards funds like this is the geographies in which they’re now operating.

Being a Singapore-based fund, Dotta sees Southeast Asia as EFA’s bread and butter. But over the last two years, new markets have been opened up by virtue of shrinking bank presence and risk appetite.

He explains: “China was completely closed to companies like us only a few years ago. Companies were making way too much money to bother with expensive overseas trade finance funds, but with what’s happening there, there’s opportunity now. For the first time in many years we have Chinese-based borrowers in our portfolio.

“Another area of development is Australia, where the banks have been affected by the commodities crash. In agriculture or mining, you can imagine the exposure they had to the larger players. As a result, some mid-market players of the more non-mainstream commodities were exited by the banks. So we see more opportunities in sectors like cattle and wheat,” Dotta says.

It’s a trend you see with other non-bank financiers as well. Falcon Group, for instance, has recently expanded its presence Down Under, opening a branch in Perth to finance mid-market companies in which the banks have no interest. You can read elsewhere in this issue about the cutthroat nature of trade finance between the big four Aussie banks, but the hits they took after the commodities bust has clearly left them chastened, leaving the door open for the likes of EFA and Falcon to move in.

Perhaps indicative of its growing market stature, in November last year, EFA announced that it would take over as investor manager of Galena Asset Management’s commodity trade finance fund. The fund was set up in 2010 by Galena, a subsidiary of Trafigura, to invest in mid-term structured trade and commodity finance transactions originated by banks and traders. Since then, it has generated on average 5% returns per month, without any negative months. The acquisition has allowed EFA to participate on syndicate deals at the same level as banks, who need the excess liquidity provided by Galena.

In a sense, EFA has graduated to the big league, and while Dotta always says that they “can’t compete with the banks”, there are some signs that they are. “There’s an amazing thing that’s been happening over the last five years in terms of human capital,” he says. “The number of senior guys, managers in their 30s and 40s that want to join a boutique fund management house like us is interesting. Over the last five years the quality of people joining the organisation is something I would never have thought was even possible.”

Eric Wong, TCG Capital

In 1918, Eric Wong’s grandfather started a business making indigo dyes for industry in Shanghai. He was in the right place at the right time, Wong says, and was able to grow the business as a joint venture with the company that would eventually become Honeywell, one of the world’s largest producers of performance materials. It went on to expand to Hong Kong and Taipei, with the last manufacturing function being sold to the Koch brothers two years ago.

Almost 100 years on, the company is now solely an investment vehicle. But Wong is continuing the scientific heritage: he studied chemistry in the US before going on to work with the Food and Drug Administration there. He was then lured back to work for his family’s investment portfolio, which goes under the name TCG Capital, an office established in 2003. TCG Capital has a trade finance fund worth US$100mn and Wong now runs it, travelling the world looking for places to invest.

“I am looking for Hong Kongs all over the world,” he explains to GTR over a drink in (the original) Hong Kong. Rather than funding trade in Asia, Wong looks for opportunities in less-heavily banked regions. In Hong Kong, he says, everything has to be collateralised by property. In less property-driven markets, you can operate on a cash and carry basis, which suits a small family fund like his.

His research has found “Hong Kongs” in Latvia, Rwanda and Uruguay – countries that sit next to trading giants and with plentiful resources, and which present substantial trade financing opportunities. There aren’t too many banks willing to finance a fertiliser export from Latvia to Burkina Faso. The deal also had tentacles in China and Russia as providers of elements for the final product, which is mixed on the ground in Africa and sold to farmers.

“Some of the smaller agricultural producers in emerging markets need longer-term financing from equipment leasing and pre-export financing and not just post-export financing to attain scalability and efficiency, and for this type of financing it is fair to demand a higher yield. The more niche the product, generally the better the yield. Unlike banks, we’re willing to look at the difficult transactions and move quickly on them. We’re kind of like a traditional merchant bank, in that we’re trying to capture trades all over the world using our local infrastructure in each region,” he explains.

With his shirt unbuttoned down his chest and a steady flow of martinis galvanising the conversation, Wong looks every inch the hedge fund manager. But whereas that industry is often associated with risky investments, Wong is playing with his family kitty. Every decision has to be justified.

“After the financial crisis, the family wanted yield,” he explains. “I was given a mandate to look for yield, but yield that delivers exactly what it promises. Trade finance is short-dated and collateralised. We usually opt for steady mid to high-single digit yield but if it’s a more aggressive deal, we’ll take mid-double digit, or higher. I use a barbell analogy, you have deals on both sides of the bar, weighted with their pricing versus their risk.”

Wherever possible, Wong tries to see the product he’s going to finance before he commits cash, and this is where his scientific background comes in handy. When a trader in Myanmar approached him about funding oil out of the country, Wong was full of questions about the quality of the oil, the consistency and the chemical structure.

He explains: “We were not satisfied with the oil quality. Trade finance is a game of details and sometimes large investors may not have the bandwidth to dive into the details. It’s easier to teach a scientist finance than it is the other way around.”