After a chastening few years, banks in the UAE have had to grow up quickly. Finbarr Bermingham reports on a sector that’s still finding its place in the world.

Four years ago, the investment vehicle Dubai World asked all of its creditors to extend maturities on its US$59bn debts (74% of Dubai’s total sovereign debt) by “at least six months”. With coffers left as dry as the arid desert air, markets panicked; contractors downed tools, financiers withdrew. Dubai – the towering emblem of Middle Eastern wealth and power – became an abandoned building site. But four years is an improbably long-time in the Dubai skyline.

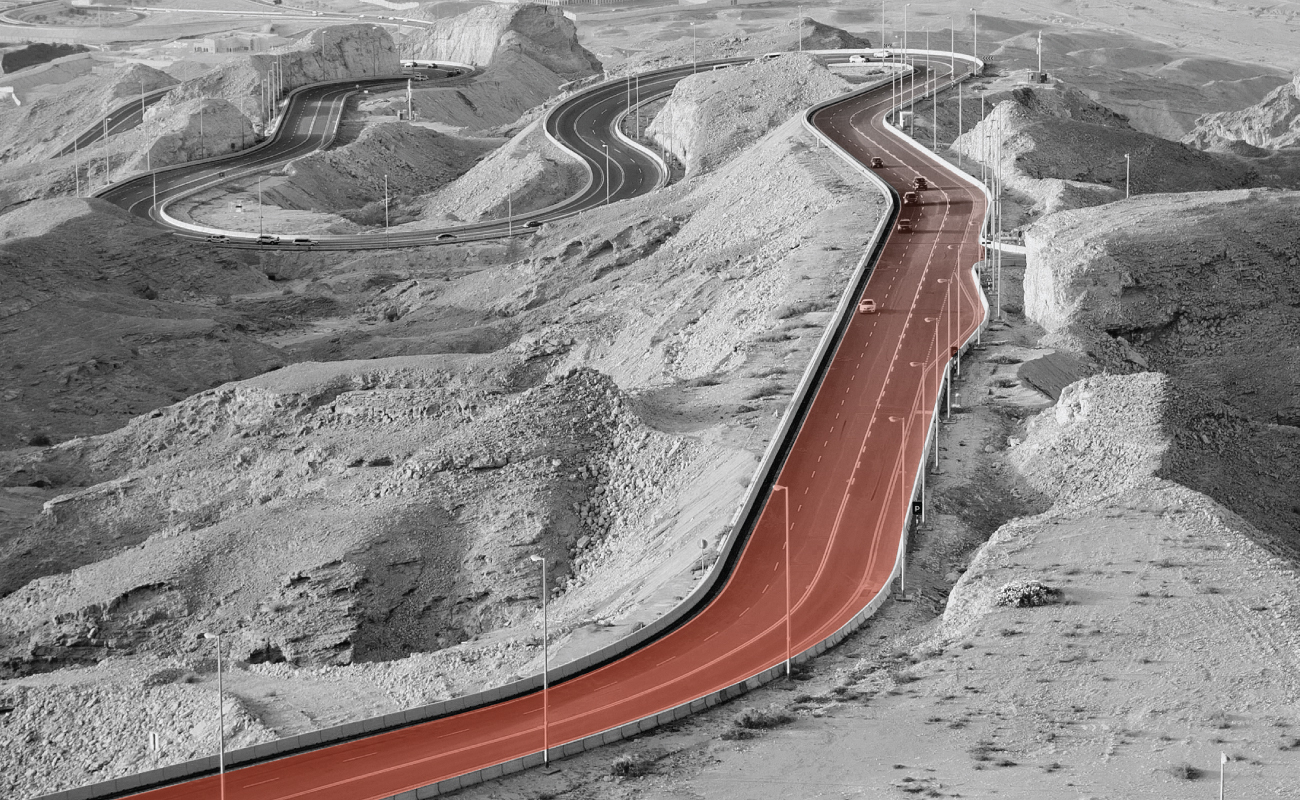

Driving into the city from Abu Dhabi, there are half-finished buildings to be seen all over the place. Now, though, the construction sites are manned. Newly-completed skyscrapers wink confidently in the scorching sun, a symbol of the optimism sweeping much of the UAE and the wider GCC.

Change has been rung out across the business community too. Of the cranes stretching out across the Gulf, many now belong to Korean or Chinese contractors, as opposed to Spanish, French or Japanese. Four years ago, many of the projects were bankrolled by western banks, a great number of which had their fingers burnt. The physical holes in the ground have been replaced by a figurative hole in the trade and project financing requirement, into which local and regional banks have needed to step.

“There’s good credit quality – a lot of it,” Frank Hamer, global head of transaction banking at National Bank of Abu Dhabi (NBAD) tells GTR. “There’s liquidity in the system that needs to be deployed.”

In Doha, banks have beefed up ahead of the pre-World Cup infrastructure boom. Most of the main players have raised funds through sukuk issuances; with some issuing shares (Doha Bank doubled its share capital in Q1 of this year, raising US$1.6bn in the process). It’s led to large infrastructure projects being funded without the assistance of foreign banks. In October, a syndicate of Mashreq Bank, Barwa Bank, Qatar Islamic Bank and Union National Bank lent US$576mn to a line of the nascent Doha Metro project.

When foreign banks withdrew Dh100bn (about US$27bn) from the UAE’s banking system, the ministry of finance bailed the banks out with emergency loans. This year, many have made the final repayments on the loans. NBAD settled the remaining Dh1.5bn of its Dh5.6bn bailout in June, while Emirates NBD of Dubai has reimbursed the treasury to the tune of Dh7.8bn this year. The Emirates interbank offered rate (Eibor – the rate at which local banks lend to one another), is at an all-time low of just over a single percentage point. In 2008, Eibor hovered over 4.5%. The UAE’s banking system is awash with liquidity that needs to find a home.

Moving down the food chain

Over 90% of businesses in the UAE are SMEs. With a population of around 9 million, there is a small business for every 39 people. Given the fact that a significant portion of the population is made up of labourers from India, Nepal and other parts of south Asia (who have little, if any, disposable income), relatively few SMEs are producing goods for domestic consumption.

Even two-man operations are hoping to capitalise on Dubai’s status as an exports and re-exports hub. “You can have a micro-firm in Dubai that employs two people, but could do Dh30mn a year in re-exports,” Ashraf Ali Mahate, head of export market intelligence at Dubai Exports tells GTR.

So whereas the Qatari government is encouraging local banks to splurge on massive infrastructure projects, its UAE equivalent is making real efforts to boost the level of lending to SMEs. It’s estimated that just 3.8% of local bank funds go to the sector, with most of it being lent to the minority at the top of the food chain. Dubai’s Chamber of Commerce and Industry has set the local banking sector a target of increasing its lending base to SMEs to 24.3%. The need became more pressing in June, when it was reported that HSBC, one of the most dominant western banks in the Middle East, was cutting back its SME lending in the UAE.

Despite the low figures, banks GTR spoke with on a recent trip to the region seemed confident that they could step up to the plate.

“It’s quite natural that domestic banks finance SMEs,” says Hamer of NBAD. “It happens in every region in the world. You know the customer base better. If you’re a foreign bank with a branch in the country, you need to have a larger portfolio to make money. You will have to invest in credit risk management and analytic resources. Domestic banks already have the branches and infrastructure around credit risk management. They’re in a much better position to finance SMEs.”

Ehsaan Uddin Ahmed is head of global transaction services and SME at Noor Bank. His bank is one of the newest players on the market, having been set up in 2008 as a shariah-compliant commercial lender, mainly concentrating on the SME market. But he’s noticing that other players, previously more associated with wholesale banking, are coming into the space.

He continues: “Many banks are coming into the sector in a big way. Competition is heating up. It’s a growing market and wallet for many players, provided they play right. You need to have the right strategies, must invest in people, systems and infrastructure, and also have the credit appetite. If all of that comes together, you have a strong proposition. But not everybody in the market will be able to do it well.”

In May, Noor Bank pledged Dh5bn worth of financing to SMEs in the UAE over the next five years. The previous week, Doha Bank allocated Dh5.5bn to small businesses in the Emirates. Banks are following one another in pledging their capital to SMEs, but what has sparked the change?

“There are three reasons,” says Ahmed. “Previously there were fewer banks, banks had less funding and finally, the sophistication of the SME wasn’t there for some segments.”

The time-honoured tale of SME unreadiness is certainly not indigenous to the UAE. But the government has been working with the IFC to try and improve conditions. Currently, there is no registry of movable assets in the UAE, which means SMEs can’t use machinery or similar assets as collateral for loans. The IFC has been consulting the UAE government to draft legislation which will allow banks to confirm the assets exist and in the case of default, take ownership of them.

There is also a central credit bureau in the works, which will allow the tracking of borrowers’ credit history. At the moment there’s no central database – banks must rely on the reports of other banks and their own due diligence rather than an independently-kept and maintained record.

In addition to the structural reform, there’s a plethora of government initiatives to encourage SMEs to export and banks to lend to them. The Dubai Multi Commodities Centre (DMCC) and Jebel Ali free trade zone are among the facilities that provide small businesses with favourable trading environments (SMEs are thought to make up around 80% of the companies based in both). The Khalifa Fund provides SMEs with funding, both directly and via the banks, which can access capital at favourable rates. Dubai SME, a public sector body designed to encourage entrepreneurship among the population, can provide guarantees for commercial loans.

The tipping point

Indeed, speaking to anyone involved in trade in the UAE and the word “sophistication” seems never to be far from their lips. But just as banks are keen to see small businesses become more nuanced in their operations, there seems to be frustration as to the methods used in some areas of banking as well. Speaking with banks in both Abu Dhabi and Dubai, there is eagerness to migrate to more advanced forms of structuring transactions.

Murali Subramanian, head of transaction banking at Abu Dhabi Commercial Bank (ADCB) estimates that 85 to 90% of UAE trade now gets done on an open account basis, with the remainder using letters of credit. There has certainly been progress, he says, but more needs to be done. There are four banks in Abu Dhabi offering structured trade and supply chain finance solutions. He hopes ADCB will be the fifth.

He continues: “The market is very paper-orientated. Factoring is relevant – the banks that offer it and physical supply chain solutions have been doing so for many years. It’s not market leading, but if more banks were to do the same there would be greater visibility for all these offerings. I was at an SME conference today and the discussion was on SME funding. We discussed the necessary products and factoring featured prominently. The consensus was it has far more room to grow for SMEs.”

At Noor Bank, the focus has been on expanding and refining Islamic finance transactions. Earlier this year, the bank worked with Dubai Commercial Bank and DMCC to structure the first murabaha transaction on the DMCC’s Tradeflow platform. “There is a significant amount of murabaha commodity transactions that happen across the Islamic banks,” says Ahmed at the bank. “The proof of concept will open up a huge opportunity for Islamic banks on the trade side.”

Perhaps, though, it’s possible to view local banks’ work on the world stage as a barometer for what sort of progress they’ve made in recent years. We’re more frequently seeing Emirati banks participating on large international deals. First Gulf of Abu Dhabi has been involved as a mandated lead arranger and bookrunner in a number of large revolving credit facilities for commodity trader Gunvor in Singapore. First Gulf and NBAD were among the arrangers of a US$300mn loan to Sberbank of Russia in June.

Those at NBAD speak of the bank’s ambition to be the primary financier for the growing east to west trade corridor. But such ambitions aren’t all that common in the region. Many are content to pick off the abundant opportunities closer to home. Pre-empting the Doha Metro project, local banks were the main players on a syndicate providing US$1.28bn to Etihad Rail for rail projects in the UAE in February. In April, there was heavy local bank involvement in the near-US$7bn financing package setup for Dubai Aluminium’s Emal II project (with a US$475mn Islamic component). For those that decide to keep their business closer to home, it seems that there’s plenty of it to go around.