Letters of indemnity enjoy wide usage in the oil trading business and allow cargoes to be sold quickly without waiting for paper bills of lading to arrive. But as Jacob Atkins reports, the failure of an oil trader two years ago shows how this practice can go badly wrong, leaving companies on the hook for tens of millions and triggering years of legal warfare.

In June 10, 2020, a Wednesday, the Torm Hardrada was unloading 40,000 tonnes of jet fuel at the United Arab Emirates port of Fujairah, destined for oil trading giant Vitol.

The Persian Gulf is calm and sun-drenched at that time of the year, but it was a wild time to be in the oil – and commodities – business. The world was five months into the Covid-19 pandemic. Demand for jet fuel had fallen off a cliff and only weeks before, the price of West Texas Intermediate Crude had dipped into negative territory for the first time in history.

In the Middle East and Asia especially, traders were already falling. Some were alleged to have been carrying out fraud for years and finally fell apart when liquidity evaporated. Others were simply so roiled by price shocks that they couldn’t survive as their banks took flight from commodities finance.

On that summer’s day in Fujairah, the 46,000-tonne Torm Hardrada was just beginning its odyssey into the tumult of one such collapse.

To start with, the ship wasn’t meant to be in the UAE. Gulf Petrochem, a mid-sized UAE oil trader, had loaded the jet fuel in Saudi Arabia on May 20, with Rotterdam the original intended destination. Natixis, a French bank active in trade and commodities finance, had financed the purchase of the cargo on board.

Natixis had issued a standby letter of credit and held the original bill of lading for the cargo. In a run-of-the-mill commodities finance transaction, the lender would be repaid, and glean a small profit, when the fuel was sold in Rotterdam. The bill of lading was security for the financing.

In the seemingly unlikely event anything went awry at Gulf Petrochem, Natixis would still have its title to the jet fuel to fall back on. Or so the thinking went.

On June 6, in an email beginning “Good Day!”, Gulf Petrochem ordered the vessel’s master to set course for the sprawling oil storage facility at Fujairah and discharge the cargo into two tanks at Vitol’s terminal there.

Because the bills of lading were sitting in Natixis’ office in Paris and would not be available, Gulf Petrochem instead issued what is called a letter of indemnity to Torm, the ship’s owner. Like most letters of indemnity, it promised that Gulf Petrochem would pay compensation if the shipping company was left in any way out of pocket as a result of the change in destination, buyer and the absence of bills of lading – for example if a bank later claimed ownership over the cargo that had been sold.

The speed at which oil barrels are bought and sold and the often lengthy list of parties that might be involved in one transaction mean physical bills of lading simply cannot keep up as they are couriered between bank offices and trading houses around the world.

So while in broader commodities trading the bill of lading is generally considered supreme, in the oil business the use of letters of indemnity to allow discharge and sale of cargoes is widespread.

But a letter of indemnity is only as good as the creditworthiness of the trader issuing it. What Torm, Natixis and a phalanx of soon-to-be highly litigious banks and creditors didn’t know was that Gulf Petrochem was about to find itself in dire financial straits.

For reasons that remain unclear, after rerouting the cargo to the UAE and issuing its letter of indemnity to Torm, Gulf Petrochem ignored its agreement with Natixis and organised to have the payment for the cargo transferred to a bank account under its sole control. From there, it was subsumed into the coffers of a company battling to stay afloat.

Months later in October 2020, when the Torm Hardrada was expected to dock in the US, Natixis scrambled lawyers in New York to secure an order for the vessel’s arrest. Torm agreed to furnish Natixis, via its insurers, with a security of just over US$11mn to cover the bank’s claim. In turn, Torm demanded that Gulf Petrochem honour its obligations under the letter of indemnity, a legal campaign that continues to this day in the English and Indian courts.

Natixis was certainly not the first bank to initially lose money on financing a Gulf Petrochem cargo in the first half of 2020. And Torm is not the only shipping company to be ultimately burdened with such a loss and now chasing Gulf Petrochem through the courts.

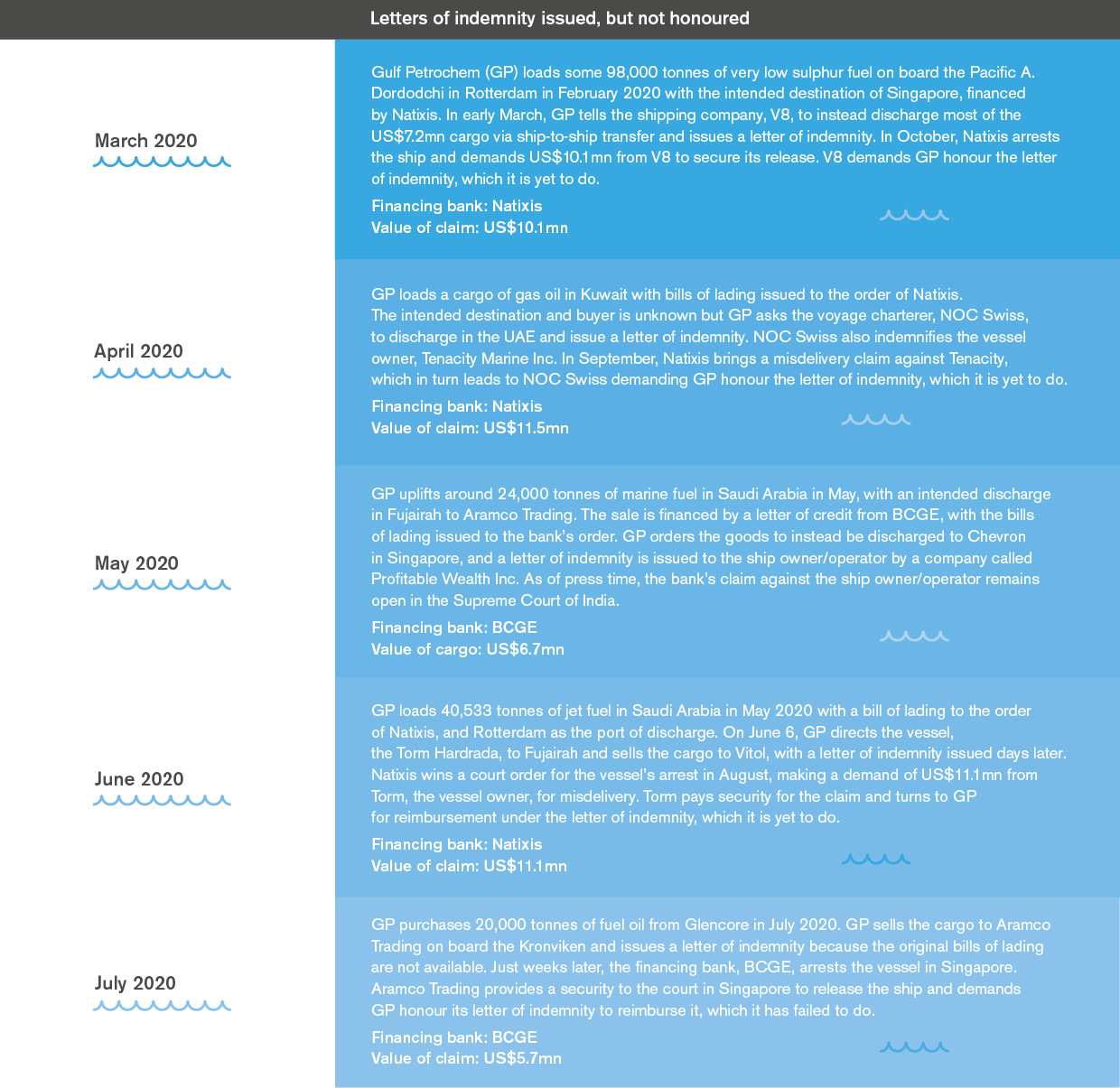

According to hundreds of pages of court judgements, orders and filings reviewed by GTR, the pattern would be repeated on at least five occasions between March and July 2020, with banks battling to recoup losses of more than US$40mn they were supposed to be paid, triggering a flow of claims down to shipping firms, and finally to the door of Gulf Petrochem.

The events ensnared dozens of shipping companies, banks and insurers, with legal battles over the misdirected cargoes waged in Antwerp, Dubai, Delhi, London, New York and Singapore.

In addition to Natixis, two banks in Switzerland – Banque Cantonale de Genève (BCGE) and the Swiss commodities finance unit of UniCredit – would be caught up in the scandal, along with maritime firms Euronav, Navig8 and the oil giant Saudi Aramco.

Gulf Petrochem’s four shareholders, Sudhir, Ashok, Manan and Prerit Goel, have kept quiet since the storm broke and are believed to be in India, according to court proceedings there. Ashok is Sudhir’s brother while Manan and Prerit are his sons, according to a 2016 article in Arabian Business magazine. The Goels did not respond to emailed questions from GTR.

In a court action in India, Torm alleged that the Goels “have defrauded many more companies globally in a similar manner by inducing shipping companies to deliver cargo to other buyers without production of the original bills of lading on the basis of similar letters of indemnity and, thereafter, not honouring the said letters of indemnity”.

In a December 2020 judgement dealing with three of the claims against Gulf Petrochem over the diverted cargoes, an English judge found that the claimants’ case that Gulf Petrochem’s conduct was fraudulent “appears to be likely on the material currently available and is not apparently disputed”.

However, FTI Consulting’s Rod Sutton, who since July 2020 has been in charge of Gulf Petrochem’s parent company GP Global, does dispute it. He says the undertakings were issued in good faith, but the company simply ran out of money.

The letters of indemnity “were not issued with an intention not to pay them back”, Sutton, who was appointed as GP Global’s chief restructuring officer after the banks walked, tells GTR. “What had happened in the interim period of time, is that [Gulf Petrochem] lost all its banking lines, and didn’t have the working capital to pay them back.”

On the at least five occasions in which the funds intended for banks were directed to Gulf Petrochem’s own accounts, Sutton says “in general, [the money] went into normal working capital, keeping the company afloat…we demonstrated that none of that money flowed back to the Goels”.

The circumstances surrounding the demise of Gulf Petrochem and its parent, GP Global, have never been fully explained. Creditors’ reports prepared by GP Global have said that a refinancing or sale to a white knight are unlikely due to banks’ wariness over “accounting irregularities” and “irregular commodity trades and/or fictitious trades where there was no actual transfer of any underlying cargo”.

The company’s directors at one point blamed rogue employees, but prosecutors in the UAE have not yet acted on a police report filed by the company.

Sutton is managing a process he describes as a “controlled wind-down to obtain maximum value for the assets”, while avoiding the blunt tool of a UAE liquidation, which he says would leave creditors with virtually nothing.

For Tat Yeen Yap, managing director for Asia Pacific at fintech MonetaGo, which specialises in tackling trade finance fraud, the cases demonstrate just how badly things can go wrong when relying solely on letters of indemnity.

“Buyers, financiers and carriers all bear enormous risks when they agree to transact based on letters of indemnity,” he says after reviewing some of the key documents in the litigation against Gulf Petrochem for GTR. “Based on public records, it appears that all three categories of actors dealing with GP have been victims of its expedient use of letters of indemnity.”

Yap says the case highlights the risks of allowing a letter of indemnity to “be inserted” into the delicate delivery of documents, goods and payments which comprise a trade transaction.

Five worthless letters

The saga of the Torm Hardrada was only one of three cases identified by GTR in which Natixis would have to sic its lawyers on a tanker owner over an alleged misdelivery. The first pre-dated Gulf Petrochem’s publicly known financial troubles by several months.

In February 2020, around 98,000 tonnes of very low sulphur fuel was loaded onto the Pacific A. Dorodchi tanker in Rotterdam, bound for Singapore. The following month, Gulf Petrochem issued new instructions to vessel owner Navig8, ordering the ship instead to Fujairah and instructing it to discharge 72,000 tonnes of the cargo to an unknown buyer via a ship-to-ship transfer to the vessel Prestigious. The remainder of the cargo was delivered to a storage facility at Fujairah.

What happened between Natixis, Navig8 and Gulf Petrochem in the intervening months is not known, but on October 15, 2020, the Pacific A. Dorodchi was arrested by a court in Antwerp.

Natixis said in a lawsuit that it was holding five bills of lading for the fuel that had been offloaded in Fujairah. Instead of selling the cargo to Natixis’ approved buyer, which would pay the bank, the cargo had vanished. The lender claimed it was out of pocket by US$7.26mn because of Navig8’s “misdelivery” and demanded a US$10.1mn security from the shipper to release the vessel.

So, just like Torm, Navig8 hired lawyers and turned to the document that is supposed to protect it in this exact situation – the letter of indemnity from Gulf Petrochem.

Around the same time a little-known trader and shipper, NOC Swiss, was also demanding Gulf Petrochem’s compliance with a letter of indemnity the latter had issued to it in mid-April 2020.

Many of the documents in the case have not been made public, but those that are show that Natixis, again, held bills of lading for a cargo of gas oil uplifted in Kuwait. The cargo was sold in the UAE under Gulf Petrochem’s letter of indemnity but Natixis was not repaid, triggering another claim. Calls to NOC Swiss were not answered and the company did not respond to an emailed request for comment.

Months beforehand, a Swiss bank had found itself in a strangely similar fracas with its client, Gulf Petrochem.

BCGE had agreed in early July 2020 to finance Gulf Petrochem’s acquisition of 19,000 tonnes of fuel oil from Glencore, and its subsequent sale in Singapore to Aramco Trading, the trading arm of Saudi Aramco, for around US$4.7mn.

Again, with the bills of lading unavailable, Gulf Petrochem provided Aramco Trading with a letter of indemnity, cited in an English court judgement, promising to “protect, indemnify, and hold you harmless from any and all damages, costs, and expense …which you may suffer by reason of the bill of lading and other shipping documents remaining outstanding”.

But instead of asking Aramco to pay the purchase price into a bank account nominated by BCGE, Gulf Petrochem requested that the money be placed into one of its own accounts with Barclays in Dubai.

With “market rumours” reportedly circulating and Sutton appointed only weeks later, it was not long before BCGE realised the prospect of repayment looked shaky. In late August the lender had the ship carrying the cargo, the Kronviken, arrested in Singapore and demanded Aramco pay security of S$7.8mn (US$5.7mn) to secure its release.

Gulf Petrochem ignored subsequent court orders in Singapore and the UK to comply with the terms of the letter of indemnity. When in mid-2021 it failed to heed an order by an English judge to pay Aramco the security, its defence was struck out and in January this year a summary judgement was entered against it, meaning a judge had found that there was no point in holding a trial because Gulf Petrochem had no reasonably arguable defence. A spokesperson for Aramco Trading did not respond to written questions.

In another case involving BCGE, the bank issued a letter of credit in May 2020 for Gulf Petrochem to purchase marine fuel from the Indian Oil Corporation for just over US$6mn and onsell it to Aramco Trading at Fujairah, according to Indian court documents.

Instead, the vessel, the MV Polaris Galaxy, was ordered to Singapore, where it discharged the cargo to Chevron on the back of a letter of indemnity issued by a company called Profitable Wealth Inc.

It is unclear what relationship Profitable Wealth Inc has to Gulf Petrochem, but a judgement issued during court proceedings in Chennai last year shows that the vessel’s master was acting on Gulf Petrochem’s orders when it discharged the cargo per the letter of indemnity.

Spokespeople for Natixis and BCGE declined to answer questions from GTR.

Directors co-operating

By the time the claims from the shipowners and Aramco Trading made it to court, Gulf Petrochem was on its knees. Its lawyers, acting for the restructurers at FTI, rebuffed every claim. Gulf Petrochem may have issued a letter of indemnity early in the year, but by October it didn’t have enough cash to honour it, the company’s new overseers said.

In early 2021, FTI brought in new solicitors at Stephenson Harwood. In December hearings for three of the claims, they added a new defence: that the person who signed at least one of the letters of indemnity did not have authority to do so.

Mark Pelling QC, sitting as a judge in London’s High Court, found neither of those arguments amounted to a reasonably arguable defence that could be put forward at a trial. Torm, V8 and NOC Swiss were granted summary judgement and the battle will now turn to the courts of countries where Gulf Petrochem and its directors have assets: chiefly, India and the UAE.

Torm has already begun that process, winning a temporary injunction preventing the Goels from disposing of assets and requiring disclosure of their finances.

Sutton describes the claimants as attempting to jump the long queue of GP Global creditors by turning to the courts to force compliance with the letters of indemnity. “What the ship owners are saying and agitating for is to be paid ahead of everyone else,” he tells GTR, alleging they are “not interested in any reasonable discussion”.

Sutton has offered a pro-rata distribution to the claimants, the same on offer to the company’s other creditors. “I represent all the creditors in this case. How could I say to one group of creditors, ‘oh by the way, we’ve decided to pay someone something in advance and pay you guys nothing?’ Everyone needs to be treated equally.”

He is also at pains to point out that while the Goels left for India as the company foundered, it was not because they wanted to flee their creditors.

“It is true to say that the directors left the UAE because there are laws here that if you’ve issued post-dated cheques, there could be criminal prosecution,” he says. “But they have not run away. I am in daily contact with the directors and they continue to provide all the assistance they can to help me.”

The assets listed in a worldwide freezing order on assets linked to the family, won by Credit Suisse in Dubai in September 2020, include a Bentley, Mercedes, Rolls-Royce and three villas in the swanky Emirates Hills neighbourhood of Dubai. Properties in Delhi, Mumbai, London and Cardiff are also listed.

It is understood that the freezing order is still in place and Sutton says Credit Suisse has been “very supportive” of the restructuring efforts. The Bank of Fujairah has arrested four vessels belonging to GP, but Sutton says the UAE lender has limited its recovery efforts to secured assets and has “not tried to topple the company”.

One shipper, Belgium’s Euronav, has managed to extricate itself from a bank’s lawsuit over another alleged mis-delivery of Gulf Petrochem oil. It delivered a cargo of Gulf Petrochem oil to an unknown number of buyers in late April 2020 after receiving a letter of indemnity from the trader, but successfully argued before England’s High Court that it was not liable for the US$24.7mn damages claim UniCredit, which was financing the cargo, filed against it. The judge ruled that the bills of lading in the transaction no longer contained a contract of carriage at the time of discharge, leaving the bank to swallow the loss.