Thanks to surging oil prices, exports from the Middle East and North Africa are tipped to increase by almost a third in dollar terms this year, but this positive top-line figure masks a huge variance between individual economies. Eleanor Wragg reports.

After posting relatively lacklustre GDP growth in 2021, the Middle East and North Africa (Mena) region will grow by 5.2% this year, its fastest rate since 2016, according to the World Bank, which recently revised its January projection of 4.4% upwards amid elevated energy prices. While it’s the only global region expected to record a rising growth rate this year, these positive projections mask a growing gap between oil exporters and non-oil exporters, and with a volatile global geopolitical backdrop, Mena’s trade outlook faces numerous downside risks.

Export outlook

In its April trade growth outlook, the World Trade Organization (WTO) says it now expects global merchandise trade volume growth of 3% in 2022 – down from its October forecast of 4.7% and well below the increase of 9.8% seen in 2021. However, the Middle East is a notable outlier, as higher oil prices boost export revenues, allowing countries in the region to import more. As such, the WTO is forecasting 2022 export volume growth of 11% for the region, and a 11.7% increase in imports.

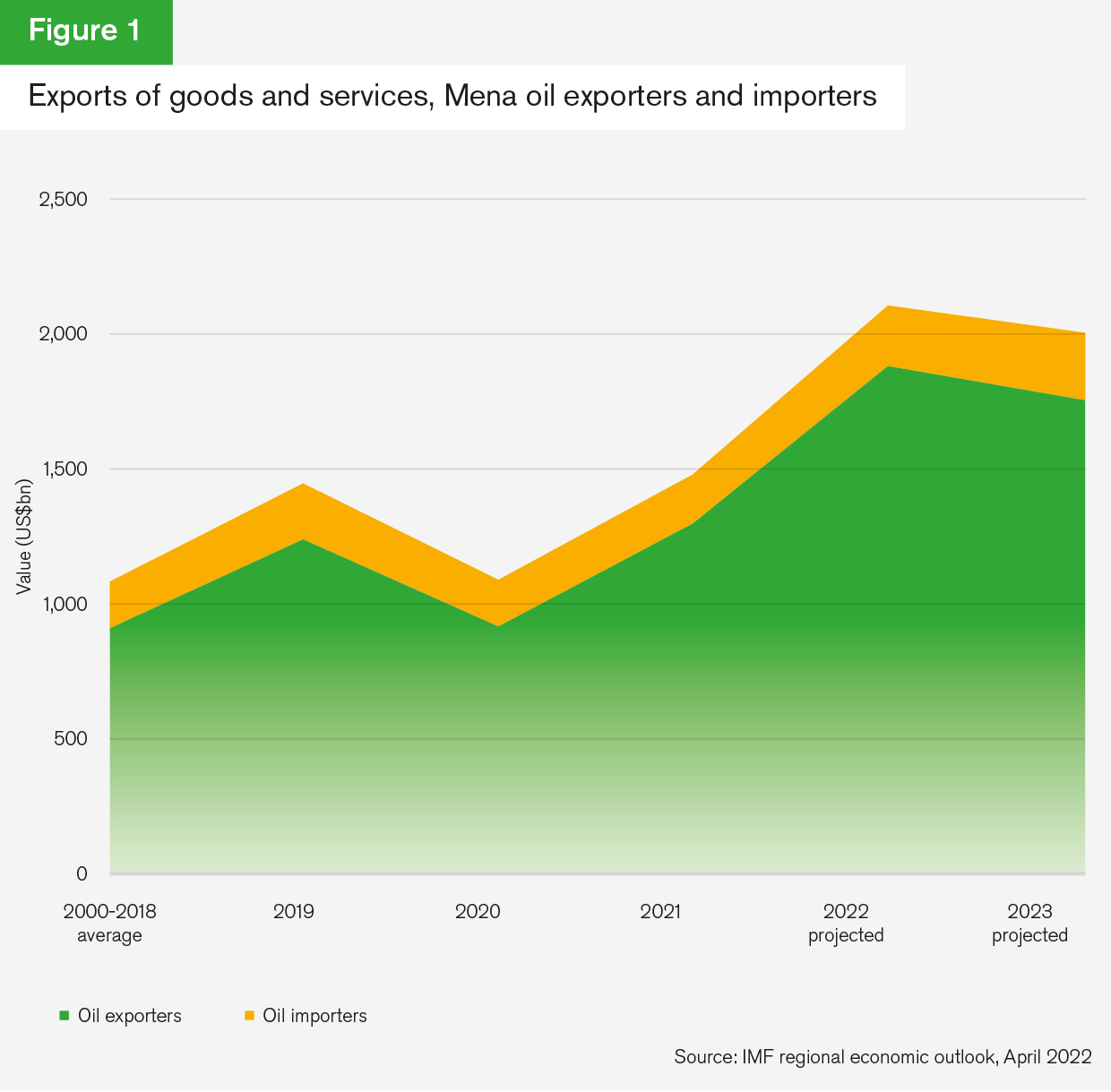

In value terms, according to the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) regional economic update, Mena exports are set to climb to US$2.1tn in 2022, up from US$1.48tn in 2021 – an increase of around 30%. As this uptick is mostly led by the recent huge run-up in crude prices, it is giving the region’s oil exporters an even larger share of overall export values than before (see figure 1).

The first half of 2020 saw a sudden and unprecedented decline in oil demand due to the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic, followed by an oil price war between Russia and Saudi Arabia when the two sides failed to reach consensus on production levels. Together, these events forced West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude to go negative for the first time on record.

By 2021, rapid changes in behaviour in the wake of the pandemic and a stronger drive by governments towards a low-carbon future led many pundits to wager that crude prices would be unlikely to top US$60 per barrel in the coming years. This looked likely to force hard budgetary decisions on oil-producing countries, where collapsing oil revenues caused fiscal deficits averaging 10.5% of GDP in 2020, according to the IMF.

That has now changed dramatically. The economic consequences of the war between Russia and Ukraine and its associated sanctions have triggered an oil price surge (see figure 2), which took a barrel of crude to a multi-year high in March this year.

While the price of Brent crude oil is expected to moderate slightly, the World Bank estimates it will average US$100 a barrel in 2022, its highest level since 2013 and an increase of more than 40% compared to 2021. Prices are expected to drop somewhat to US$92 in 2023, although this remains well above the five-year average of US$60 a barrel.

“2022 was set to be the year in which the oil sector was going to drive the recovery of the Gulf region, but also major producers in North Africa,” says Robert Besseling, CEO of specialist intelligence consultancy Pangea-Risk. “They were going to do well regardless of Cop26 commitments because China and others were continuing to finance these projects. When Russia invaded Ukraine and the oil price shot up, the oil producers suddenly saw even more benefits. Iraq is a good example: in February, it had its best month in terms of crude oil revenues since 1972.”

Increasing food prices and the spectre of civil unrest

However, it isn’t just oil prices that have risen.

The war in Ukraine has dealt a major shock to commodity markets, altering global patterns of trade, production and consumption in ways that will keep prices at historically high levels through the end of 2024, according to the World Bank’s latest Commodity Markets Outlook report.

Price increases for food commodities and fertilisers – of which Russia and Ukraine are major producers – are now the largest since 2008.

“Overall, this amounts to the largest commodity shock we’ve experienced since the 1970s. As was the case then, the shock is being aggravated by a surge in restrictions in trade of food, fuel and fertilisers,” says Indermit Gill, the World Bank’s vice-president for equitable growth, finance and institutions, in a statement.

Of particular significance to the Mena region are wheat prices, which are forecast to increase more than 40%, reaching an all-time high in nominal terms this year.

Egypt, the world’s biggest importer of the grain, gets more than 80% of its wheat from Russia and Ukraine. To try and shore up supply, it approved India as an import market in April, and plans to lift around a million tonnes of the grain from the country, according to a statement from Indian commerce minister Piyush Goyal, who added that his country has set a wheat export target of at least 10 million tonnes for 2023. However, with annual wheat imports of around 13 million tonnes per year, it’s unclear whether Egypt will be able to secure enough from alternative suppliers to meet its needs.

“For oil producers, higher revenues from their fossil fuel sectors can offset the higher import bill for food and fertiliser, thereby allowing governments to continue to subsidise these goods at below market rates,” says Besseling – although he notes that recent food protests in Iraq demonstrate that not all oil-producing countries’ governments are doing enough to make sure that food is affordable for their citizens.

“For non-oil exporters, they simply cannot match the price increases,” he adds.

Across the region, food price increases are paving the way for potential civil unrest. Lebanon, which gets 95% of its wheat from Russia and Ukraine, had already experienced an increase in food costs of 351% in 2021 as a result of its domestic financial crisis. The World Food Programme says it is now assisting one in every three people across the country to meet their basic nutrition needs.

It’s a similar story in Tunisia, which is facing growing shortages of goods, including staple foods such as grain and sugar.

“Tunisia is a tinderbox,” says Besseling. “Last year, the president implemented a ‘self-coup’, and has now banned the parliament. Jordan is also seeing political instability, with increased civil unrest between Jordanians and Palestinians.

And Lebanon, of course, defaulted in 2020, fell into a major economic, financial and political crisis through the pandemic, and is now facing the Russia-Ukraine crisis. This is the perfect ground for an Arab Spring scenario: they are importing everything, they’re not exporting crude, and they are completely dependent on food and fuel imports.”

Pulled in two directions

While the United States and Europe made their condemnation of Russia’s February invasion of Ukraine immediately clear, security, trade and oil ties with Russia made it diplomatically complicated for Mena countries to follow suit. However, after an apparent initial reluctance, almost all countries in the region have since joined the United Nations resolution condemning the war and calling on Russia to withdraw all forces from Ukraine. Only Syria, whose dictator Bashar al-Assad is backing his ally Vladimir Putin in the aggression against Ukraine, voted against the resolution, while Algeria, Iran and Iraq abstained.

If forced to implement international sanctions aimed at curtailing Russian interests, numerous countries in the region are set to lose important investments.

“Iraq is likely to lose Russian energy companies operating at several oil sites in the south and north of the country,” says Besseling. On March 1, Elbrus Kutrashev, Russia’s ambassador to Iraq, reaffirmed Moscow’s desire to maintain and expand its estimated US$14bn investment portfolio in the country, emphasising the difficulties that Iraq might face in finding alternative investors, as companies need to allocate almost a quarter of their budgets to security when doing business there.

This was swiftly followed by requests from European and US oil purchasers, which would allow Iraq to divest from Russian investments.

“Iraq is likely to embrace efforts to diversify its energy sector’s commercial links and incrementally reduce its reliance on Russian investment in the years ahead,” says Besseling, adding that this divestment would profoundly impact Iraqi Kurdistan, where the Russian energy company Rosneft holds a controlling 60% stake in its main oil pipeline. With Russia’s plans to sell gas from Iraqi Kurdistan via Turkey to Europe dashed by tightening sanctions, its prospects for lucrative deals in the Kurdistan Region are fast receding.

Another Mena country needing to rethink its investment promotion strategy in the face of the ongoing conflict is Egypt. “Egypt depends heavily on western financial aid and buys large amounts of western arms,” says Besseling. “However, it also values its warm ties with Russia.”

Russian investment into the North African country included agreements to set up two industrial zones. “One, in East Port Said, was expected to attract US$7bn in investments, with 32 Russia-based companies setting up production lines there,” says Besseling.

“Some of the zones’ factories were supposed to start operating this year, and investors include companies working in the engineering, chemicals, metallurgy and pharma industries.”

Meanwhile, although their investments in Egypt are not being directly targeted by sanctions, Russian energy companies, including Rosneft and Lukoil, are experiencing severe sanctions-related financial challenges, which could have an indirect impact on their operations in Egypt and other countries.

“The Russian invasion has put Egypt in a difficult position geopolitically, as it has close ties with both Russia and the west,” says Besseling, adding that he expects Russian investment into the country to come to a “standstill”.

Mena looks east

It isn’t only the Russia-Ukraine war that is changing the Mena region’s trade and investment relationships. Recent research by Asia House has uncovered the extent to which strengthening economic and political linkages between the states of the Gulf Co-operation Council (GCC) and emerging Asia are reshaping the global trade balance.

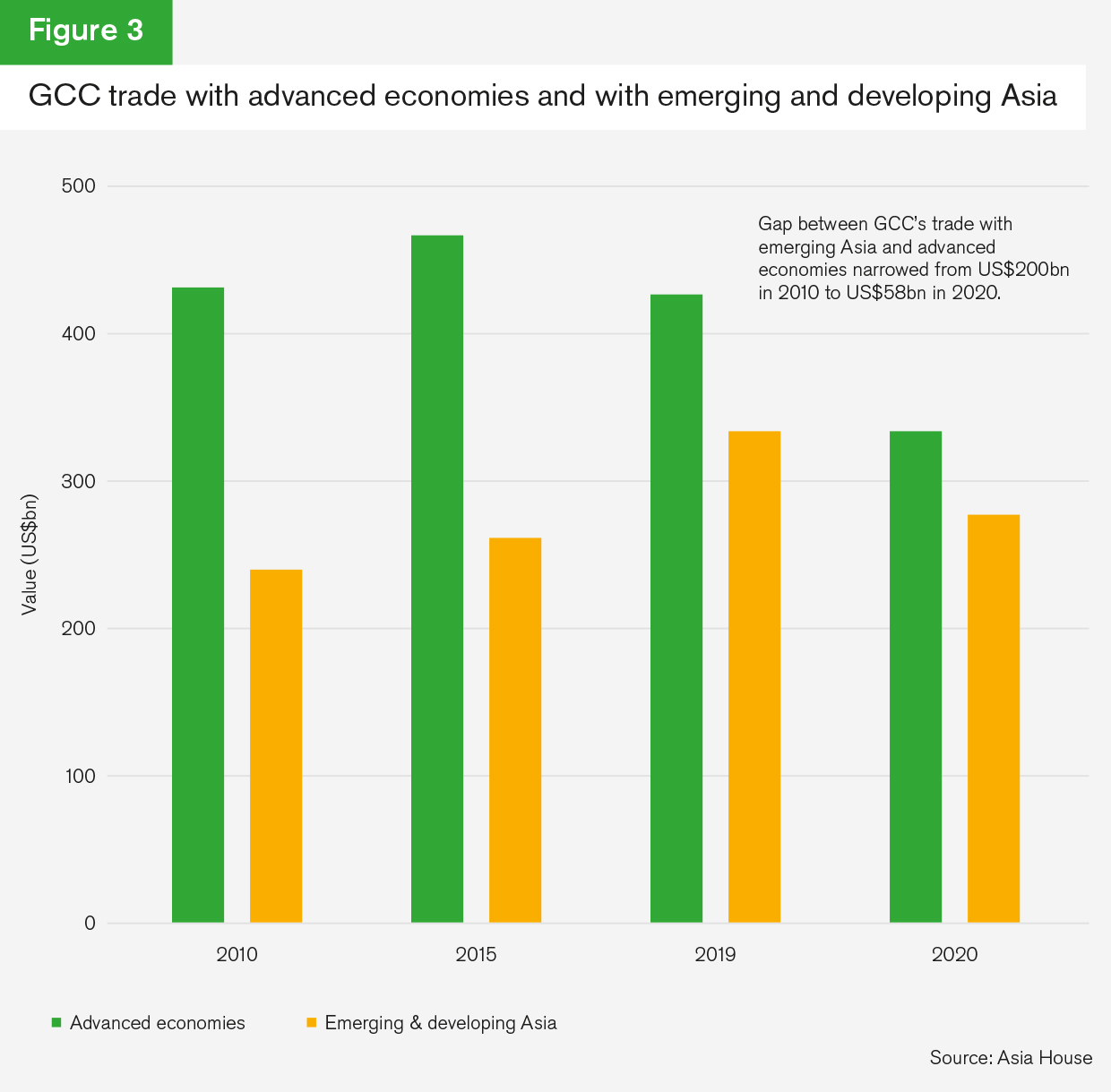

The think tank found that GCC trade with emerging Asia – a term it uses to cover the IMF’s ‘emerging and developing Asia’ list of 34 Asian economies, which includes China, India, and the majority of Asean members, but excludes advanced Asian economies such as Japan, Singapore, South Korea, Hong Kong, Macao, Taiwan, Australia, and New Zealand – grew from US$247bn in 2010 to US$336bn in 2019, representing a jump of approximately 36%. This trade corridor is not only growing but beginning to substitute GCC trade with advanced economies (see figure 3).

Interestingly, Asia House also found that the GCC’s trade with emerging Asia has also proven far more resilient during the pandemic than its trade with advanced economies.

“We have good reason to believe, taking into account compound annual growth rates and looking at future trends and drivers, that this relationship is going to continue to grow,” Freddie Neve, Middle East associate at Asia House, tells GTR. “We forecast that emerging Asia is set to be the GCC’s largest trading partner by 2030, growing to US$480bn from US$336bn in 2019, and outstripping its relationships with the advanced economies. This is going to bring opportunities for businesses in both regions, but will also have a number of geopolitical implications.”

Oil remains dominant in Mena-Asia flows

One of the most important implications centres around the dominance of oil in GCC trade with emerging Asia.

“While we have seen economic diversification over the last few years, oil exports remain hugely important, to the extent that we are probably going to see a slight reversal in economic diversification because average oil prices look set to remain high over the short term,” says Neve.

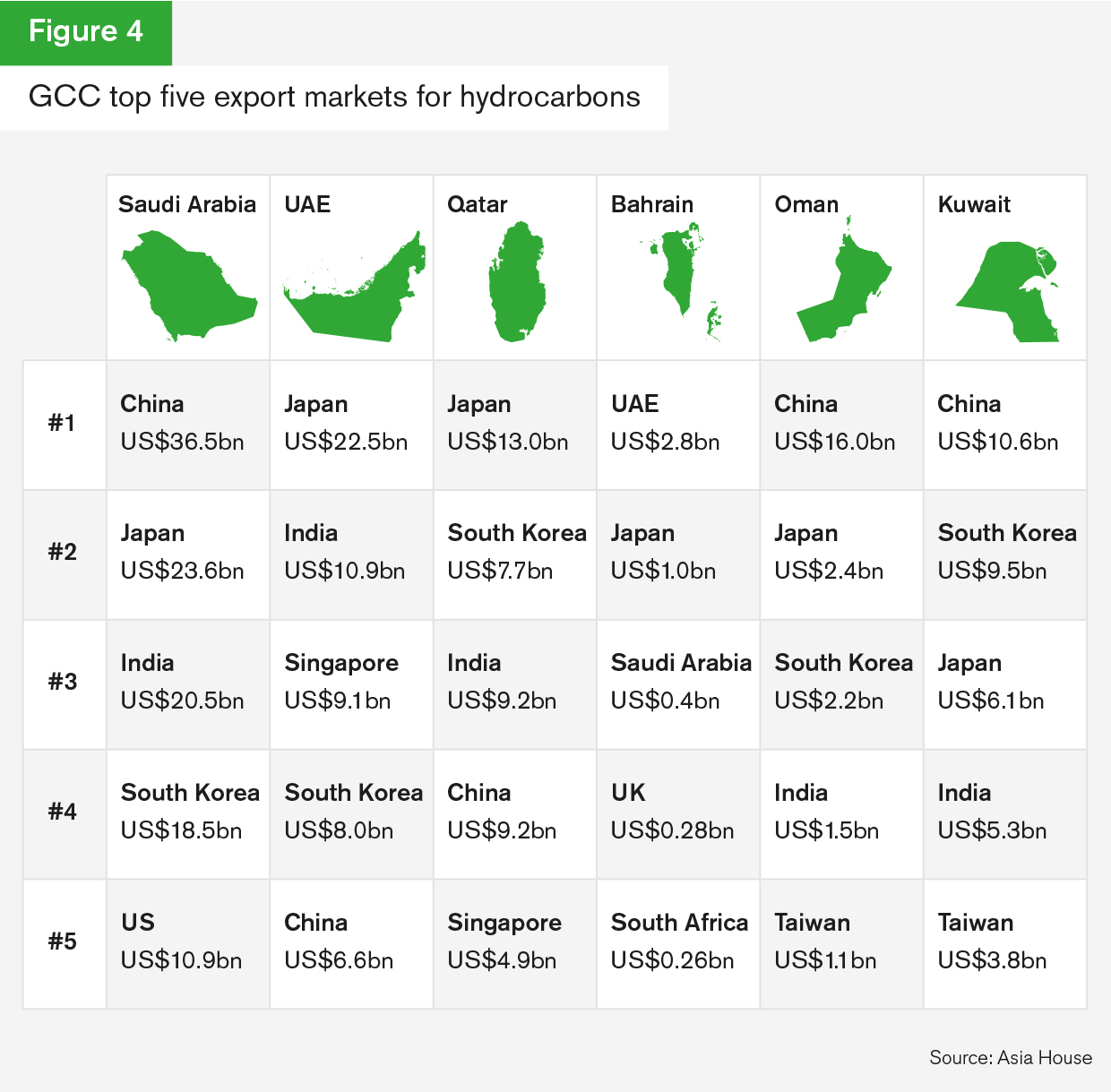

The International Energy Agency predicts that Asian oil demand will rise from 33.4 million barrels per day in 2020 to 39.3 million barrels per day in 2026, due to growing populations and an expanding middle class. Asia’s domination of the GCC’s export market for hydrocarbons is such that, despite global climate change pledges, oil will remain the GCC’s core export to the region for the foreseeable future (see figure 4).

“This creates some interesting dynamics between the GCC and Asian nations,” says Neve. “The Middle East is very much seen as key to Asian energy security, and to ensure the security of supply, we’ve seen more activity recently whereby Asia is not just investing in Gulf extraction capabilities, but also seeking Gulf expertise to develop refineries at home.”

He points to investments by South Korea in oil storage facilities in Fujairah, which would ensure continuity of supply in the event of a blockade of the Strait of Hormuz, as one example.

“However, it works both ways,” says Neve. “High oil prices also have a secondary effect of boosting GCC economies, increasing government revenue and the coffers of sovereign wealth funds, which in turn increases the willingness to invest abroad, including in Asia.”

In its report, Asia House highlights a recent uptick in investments by Gulf sovereign wealth funds into Asia.

“For example, in July 2021, it was reported that the Qatar Investment Authority was building a regional hub in Singapore,” the report says. “The Kuwait Investment Authority opened a representative office in Shanghai in 2018, its second in the country after opening a Beijing office in 2011. The Abu Dhabi Investment Authority opened a Hong Kong office in 2016 and Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund (PIF) is also reportedly studying opening a new office in Asia to ‘focus on China’.”

It adds that the most prominent of these investments is probably the investment by PIF and Abu Dhabi’s Mubadala Investment Company in Tokyo-based Softbank’s US$100bn Vision Fund, which focuses on technology start-ups and disruptors. Both contributed almost two-thirds of the fund’s capital, with PIF alone investing US$35bn, Asia House says.

“Given GCC sovereign wealth funds can reflect the strategic thinking of their countries’ rulers, this greater interest in Asia also demonstrates that Gulf leaders are increasingly seeing the continent’s strategic potential,” the report adds.

Beyond oil trade

While increased oil demand and rising oil prices look set to boost the value of Asia-Mena trade, Mena’s numerous ‘Vision’ projects and economic diversification plans will also drive greater non-oil trade.

“Oil is obviously very important to the pivot, but there is a genuine effort in Gulf capitals to diversify their economies, and this has encouraged the GCC to look towards Asia for investment and expertise,” says Neve. “The most interesting new sector from my perspective is renewables, particularly hydrogen.”

The UAE – which hopes to hold a 25% share of the world’s low-carbon hydrogen market by 2030 – already has one plant under construction in Dubai, which will source the electricity required from solar panels. Saudi Arabia’s new mega-city Neom will also host a green hydrogen plant, expected to have a capacity of 4GW.

“Asian countries see hydrogen imports from the Gulf as a potential way of helping their own decarbonisation,” says Neve. While hydrogen trade is still in its infancy, both Saudi Arabia and the UAE have sent trial ammonia cargos to Japan and China.

High hopes for the India-UAE trade pact

The historic comprehensive economic partnership agreement (CEPA) between the UAE and India, which came into force on May 1, further strengthens the burgeoning Mena-Asia trade axis. Concluded in just 88 days, the deal is India’s first complete free trade agreement to be signed with any country in a decade.

The CEPA will provide India preferential market access to the UAE on 99% of its exports in value terms, covering tariff lines such as gems and jewellery, textiles, leather, footwear, sports goods, plastics, furniture, agricultural and wood products, engineering products, medical devices, and automobiles. India will also be offering preferential access to the UAE on over 90% of its tariff lines.

The two sides say that they expect merchandise trade to increase to US$100bn over the next five years, up from US$29bn in 2019-20.

Further trade deals between the two regions are expected, with the Hong Kong Economic and Trade Office opening its first Middle East office in Dubai. “Its priority is to negotiate a free trade agreement between the UAE and Hong Kong as well as with the GCC,” says Neve.

A wobbly outlook

While Mena’s trade growth is set to outperform that of other global regions over the coming year, a good dose of realism about its prospects during these times of uncertainty is essential.

“Looking ahead, the war in Ukraine is expected to dominate the 2022 outlook, compounding the headwinds from faster-than-expected normalisation of monetary policy in advanced economies and the slowdown in China, which is a significant market for exports for many of the region’s oil-exporting countries,” said Jihad Azour, the IMF’s Middle East and Central Asia department director, in a recent press briefing.

Although oil exporters are expected to make hay while the sun shines, at least for the time being, the increase in food and energy prices as well as the repercussions of the ongoing Ukraine crisis mean that Mena’s positive trade prospects are far from certain.