Rebecca Harding, CEO of Coriolis Technologies, discusses the impact of Covid-19, Brexit and China’s dominance as a trading partner on Europe’s trade flows and performance.

GTR: The impact of Covid-19 on Europe’s trade flows is already apparent. What are the main factors behind this and how long will a recovery take?

Harding: No global region is immune to Covid-19’s impact on trade. The beginning of 2020 saw manufacturing grind to a halt worldwide; inventories collapsed and some 95 countries imposed export restrictions on key medical and food-related goods in order to protect their own national interests. In the European context, only Germany implemented export liberalisation measures during this time – every other European nation except Bosnia and Herzegovina has become more protective.1 The World Trade Organization (WTO) expects trade to fall by anything between 13% and 32% during 2020, and we are expecting Europe’s trade with the world to fall by over 16% during the course of the year.2

Between December 2019 and May 2020, the value of exports from the euro area alone fell by 23% – a similar decline to that seen at the height of the global financial crisis (GFC) between October 2008 and February 2009.3

The rate at which Europe bounces back from the Covid-19 crisis in trade terms will depend on several things: whether oil prices recover, the speed at which supply chains recover, and the extent to which global demand resumes. Economists like to talk about V-shaped, U-shaped, L-shaped or W-shaped recoveries – the shape of the letter determining the speed at which economic activity picks up. In a sense though, the shape of the letter is immaterial to the scale of the structural change that the global economy will go through post-Covid-19 that directly affects trade.

The need to keep trade and trade finance moving through the crisis has accelerated implementation of digital technologies, while greater distribution of supply chains across the world to reduce inventory dependency on single sources is an obvious reaction – irrespective of the consequences of greater protectionism and the continuing trade war between the US and China.

There are few precedents upon which to base a forecast for trade. That said, the simultaneous collapse in oil prices, equity markets and global trade through Covid-19 are redolent of the GFC.

The forecasting technique used by Coriolis Technologies therefore uses its own momentum projections from 2019-23 and adjusts these for the rates of trade growth between 2008-09 and 2011-12, in doing so picking up the entire post-financial crisis recovery and catch-up period which, post-2012, begins to factor in slower growth as a result of the European debt crisis and the collapse in oil prices.4

Of course, there are several significant differences between now and the GFC. For example, the shift of trade to Asia that occurred after the financial crisis cannot be assumed to be likely during the recovery from Covid-19, not least because of the ongoing trade war between the US and China. Indeed, China’s growth over the past 12 years has also changed the structure of its trade, from greater electronic hardware to support digital communications to more biopharmaceutical trade. In addition, China itself is now consuming more in the way of luxury items, such as cars.

Meanwhile, Europe’s internal market has also changed. While there is now more intra-regional trade, the UK’s decision to leave the bloc in 2016 will materially impact the region’s supply chains.

These changes are captured by the momentum element to the Coriolis forecast. Adjusting the forecast for the patterns after the GFC allows us to see what would happen to trade if the recovery followed a similar initial V-shaped pattern with a subsequent slowdown in the rates of trade growth as the Asian economies became more integrated into the global trading system.

It is worth noting too that at the beginning of 2020, many economists were reasonably positive about the outlook for trade during the course of the year: a phase 1 deal had been struck between the US and China, and there were signs that the global economy was pulling away from the sluggish growth of the previous few years.5

As with all forecasts, the patterns and trends simply represent a perspective on the world rather than an absolute picture of what will happen. Nevertheless, many of the projections do appear to reflect current reality at a difficult time for European, and global, trade.

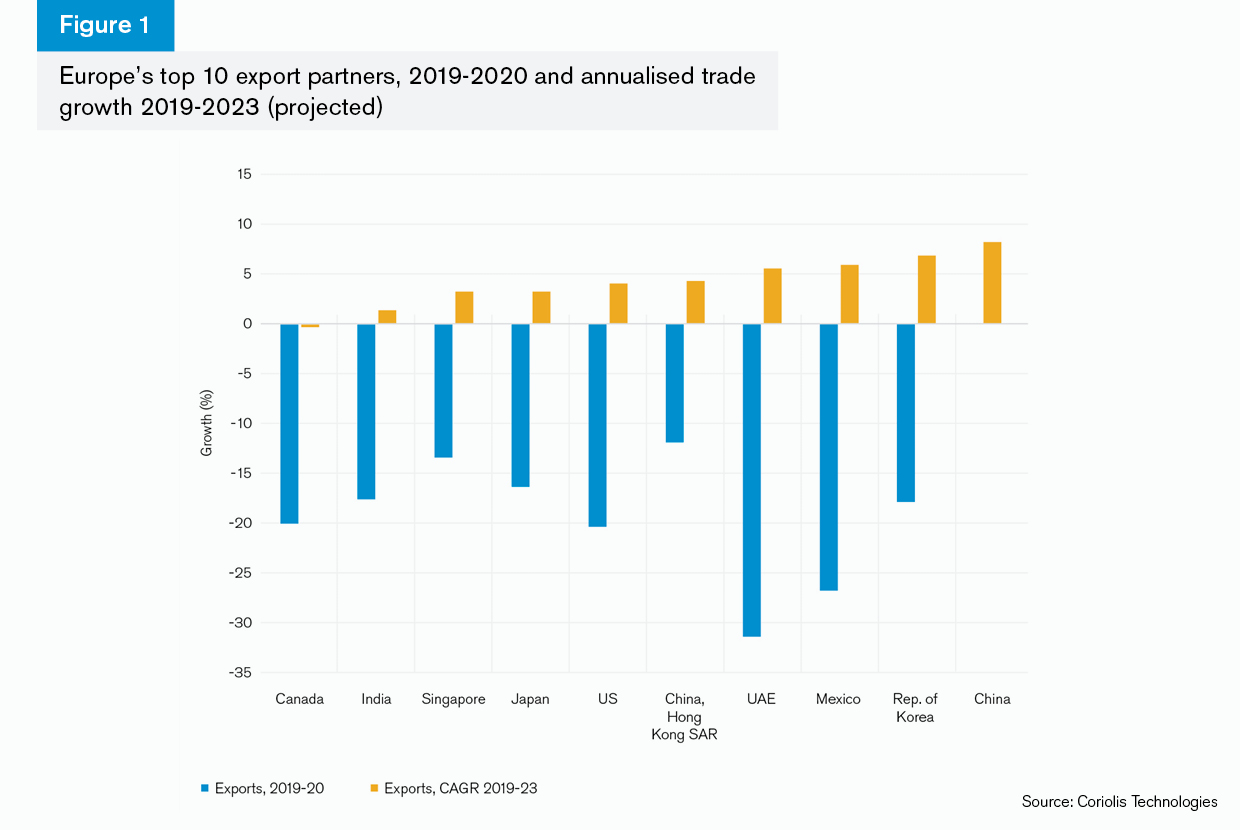

The Coriolis forecast suggests that exports between Europe and the rest of the world will fall by around 16.5% during the course of 2020. This is lower than the 19% decline in trade caused by the GFC and potentially reflects two things: first, intra-regional trade within the EU27 has been growing significantly and is already reducing the region’s dependency on external supply chains. The EU27 dominates the region’s overall trade, and this closer integration makes the region less vulnerable, except to oil price shocks. Second, the global and European economies were arguably stronger at the beginning of 2020 than they were going into the GFC.6 The forecast suggests an annualised growth rate of external trade at 2.6% to 2023 which indicates that trade’s power of recovery is quite strong and driven by its underlying momentum.

Europe’s export trade with the UAE looks to be the worst affected during 2020 although it is expected to recover at over 5% annually to 2023 (Figure 1). This is notable due to the UAE’s role as a major trade hub: a large proportion of European trade flows through its ports for re-export. The UAE represented around 12% of Europe’s trade at US$66bn in 2018 and is its seventh-largest trading partner, both in terms of bilateral trade and in terms of goods that are in transit.

Perhaps the most striking feature of Figure 1 however is the fact that Europe’s exports to China are not forecast to fall by much at all during the 2019-20 period (-0.2%). There is a downside risk to this projection, not least because the fact that trade with China grew strongly after the last financial crisis may not hold during the recovery post-Covid-19.

However, it nevertheless suggests that Europe as a whole is interdependent with China – Germany’s supply chains in automotives, electronics and pharmaceuticals, and Switzerland’s supply of precious metals (gold) and precision equipment have been growing rapidly and China’s demand recovery is likely to be quicker than that of the rest of the world, not least because it went into the crisis earlier. Similarly, Russia’s exports to China are estimated to have grown by 25% between 2016 and 2019, largely because of oil and gas, although interestingly, fish exports have become China’s third-largest import from Russia at a value of nearly US$1.8bn at the end of 2019.

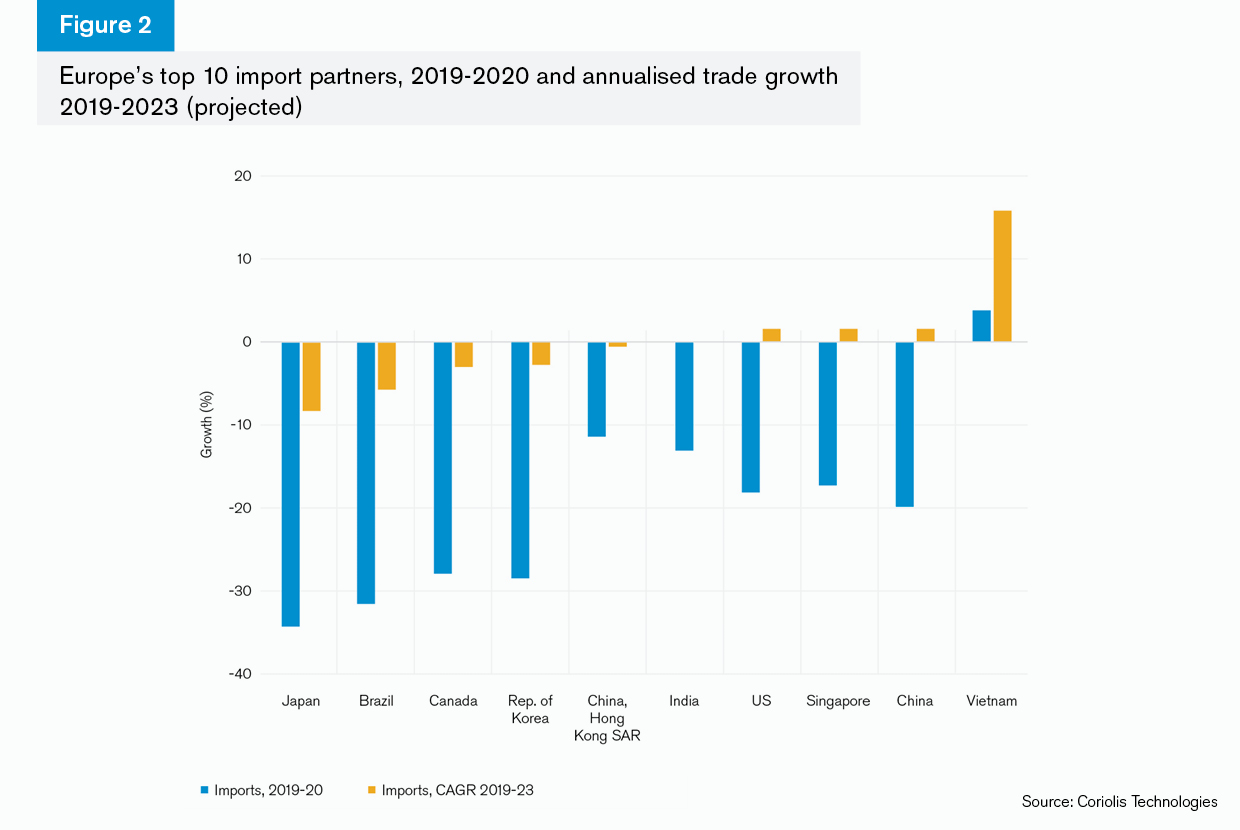

In terms of imports, all partners except Vietnam are projected to decline significantly in 2019-20, reflecting the weak demand across Europe during the coronavirus pandemic (Figure 2).

Figure 2 also shows that there is some evidence of how Europe is redistributing its import partners outside of the impact of Covid-19 and its aftermath. Imports from Japan do not look likely to recover, in spite of the new EU-Japan trade agreement, and trade with Brazil, Canada and South Korea do not look as though they will recover quickly, if at all, over the next few years. Trade with Brazil is largely in commodities, while trade with Canada is commodities and automotives-based.

There are two other striking features of Figure 2, however:

- Imports from Hong Kong are set to fall dramatically in 2020 and to continue that decline, or at least remain static, over the period to 2023. This contrasts with imports from Singapore which will decline by over 17% in 2020 but then have the potential to grow by around 1.5% annualised to 2023. Intuitively this makes sense – much of the trade that goes through Hong Kong is from China and the tensions between the US and China in particular mean that China may re-orient its own trade through ports on the mainland as Hong Kong’s “special status” is removed.7 While the trade conflict does not yet directly apply to Europe, it is likely that the redistribution of China’s trade to its own ports, and of non-Chinese Asian trade through Singapore, will have an impact on import flows into Europe from Hong Kong over the coming years.

- Vietnam is increasing its exports to Germany, the Netherlands and the UK with electrical products, footwear and machinery and components (including computers) being particularly strong growth sectors. Vietnam’s trade with Germany has been growing at over 5% annually for the last three years, and appears set to grow with the UK by around 8% annualised to 2023. This may also reflect some redistribution within the Asean region of Chinese supply chains in consumer electronics and computing as the trade war between China and the US has forced China to export its production to circumvent the impact of tariffs and sanctions, especially in the technology space.8 It is still a relatively small proportion of Europe’s total trade, but helps explain why the EU has been so keen to put in place a free trade agreement with Vietnam.

GTR: Which countries are likely to suffer the most from the pandemic’s impact on trade?

Harding: The factors underpinning the speed of countries’ recovery from Covid-19 are complex. For example, how reliant is it on commodities (and in particular oil) for its trade? How healthy were its economic fundamentals prior to the crisis, and can domestic and overseas demand pick up quickly enough for it to get back to where it was at the end of 2019? How reliant is the country upon international value chains that are affected by the collapse in trade, in particular manufacturing supply chains?

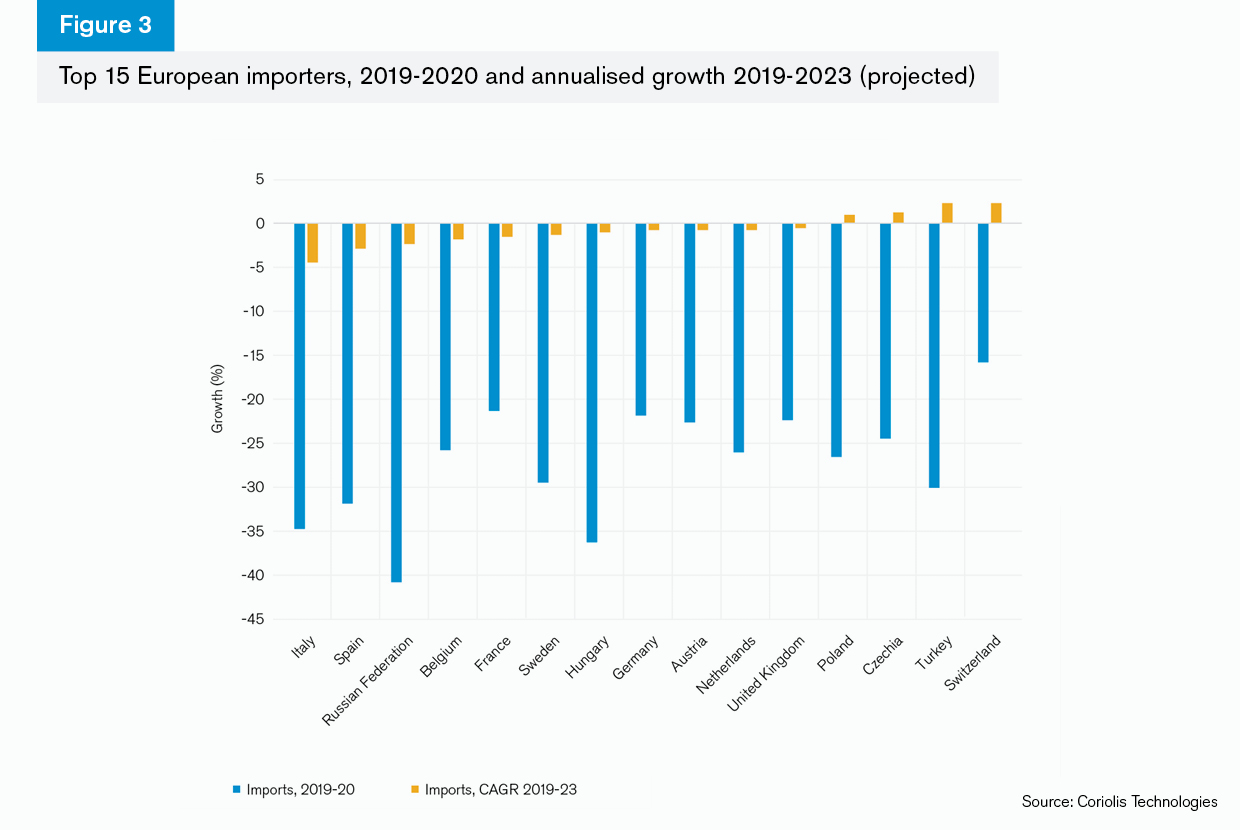

Of the largest 15 importers in Europe as a geographical region (Figure 3), Russia looks to be impacted most by the events of 2020, with a projected fall in imports of nearly 41%. This is because of its dependency on oil prices for revenues. Oil prices have fallen back significantly, and this will inevitably impact the country’s export revenues and therefore economic performance. Over the period between 2013 and 2018, Russia’s imports have fallen back at an annualised rate of nearly 4% which suggests that demand is weak in the economy and likely to contract further.

In contrast, Switzerland is likely to be the least affected in terms of imports – its major exports are precious metals and stones which include gold and diamonds. Thus its revenues are likely to be less impacted and, while the pandemic will have slowed consumer demand temporarily, the effect is likely to be short-lived with growth at over 2% annually to 2023.

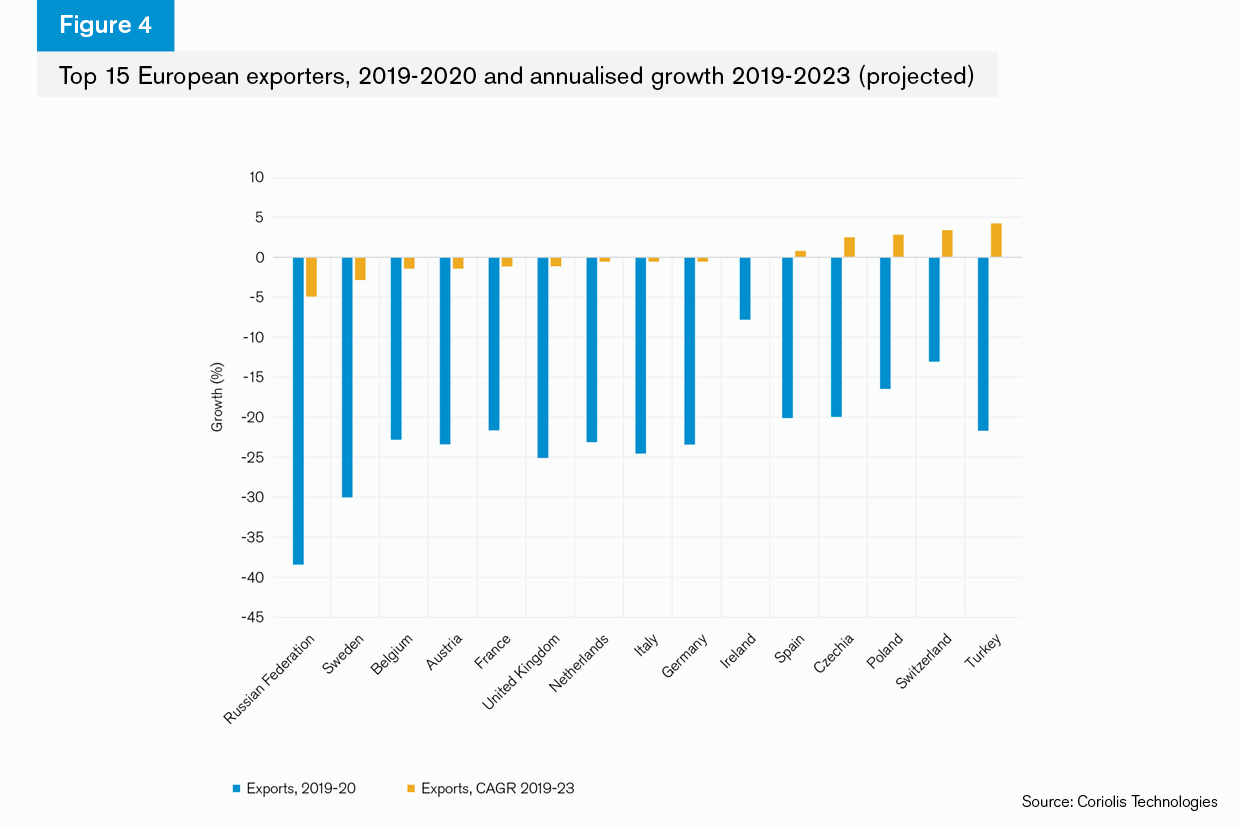

Meanwhile, of the largest 15 exporters in Europe (Figure 4), Russia is likely to be the country that is most affected, both in 2019-20 and over the period to 2023. Russia’s trade with Europe itself in oil and gas is an important part of its export revenues. Exports to the Netherlands and Belgium have grown at around 10% in value terms annually for the three-year period to 2019. Interestingly, however, although exports to Germany have risen, the rate of growth has slowed over the past three years to near zero. Germany is dependent on imports for some 63% of its energy supplies and Russia is by far and away its biggest partner, but trends before the pandemic, including its planned energy transition from fossil fuels to renewables, may underpin the reduction in growth of energy-related imports from Russia.9 Furthermore, as tensions between the US and Russia around Nord Stream 2 intensify, the risk of primary and secondary sanctions against German companies may reduce the likelihood of this trade picking up again.10

Turkey, Switzerland, Poland and Czechia will be affected by the crisis, but their exports appear to have the capacity to recover during the coming four years to 2023. Poland and Czechia may see their trade grow by between 2.6% and 2.8% respectively, which reflects several factors: their growing roles in intra-European supply chains over the past four years; the potential shortening of supply chains; and a reduced dependency on China leading to nearshoring.11 Similarly, Turkey has shifted the base of its exports over the past decade from a reliance on oil and gas to a position where, in 2019, its largest export sector is now automotives, at a value of some US$30bn, followed by machinery and components at US$18.5bn, reflecting its high-end engineering capabilities.

GTR: The EU’s trade is heavily dependent on traditional manufacturing sectors like aerospace, automotives and engineering. Is this sustainable after the pandemic?

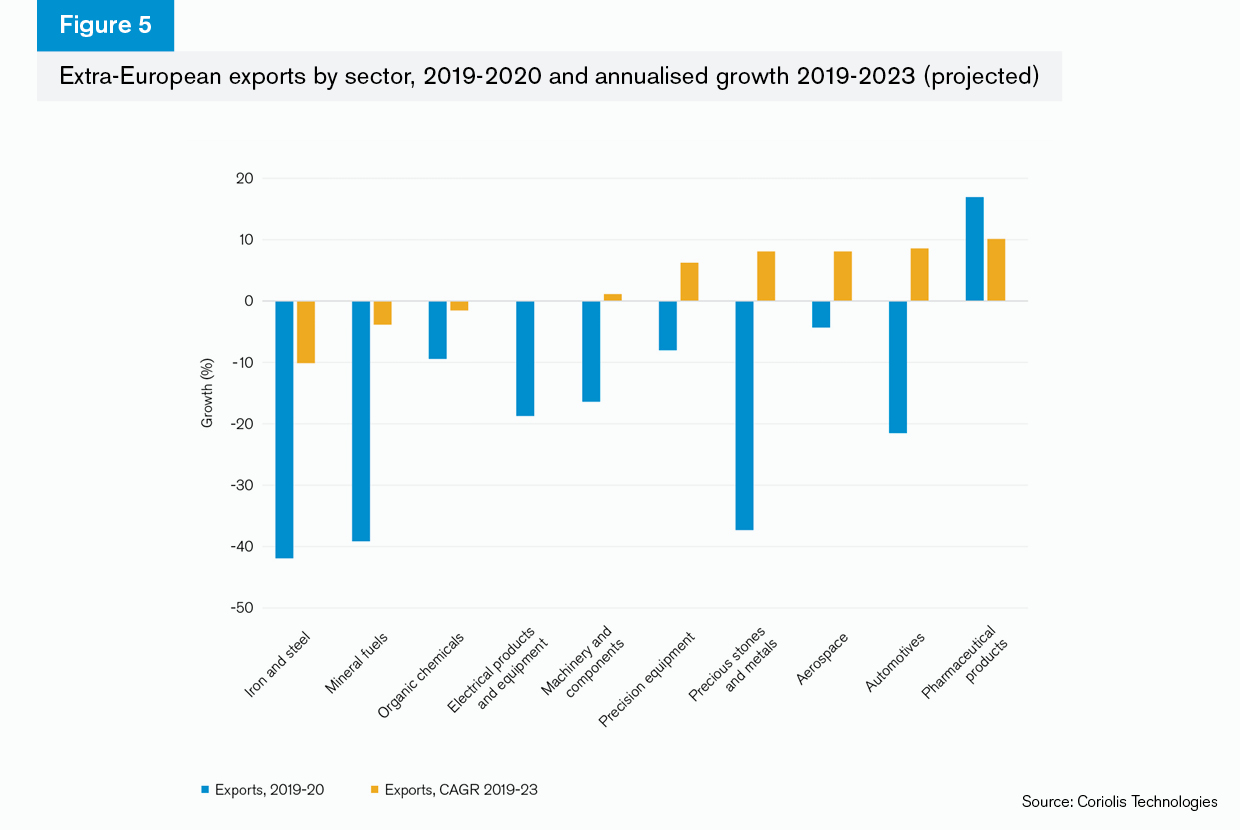

Harding: Europe’s exports are heavily dominated by manufacturing sectors. Some of these, together with commodities, such as iron and steel and mineral fuels, as well as organic chemicals, look like they will fare badly and struggle to recover significantly in terms of their extra-European export values (Figure 5).

However, we are expecting European pharmaceuticals, automotives and aerospace exports to the rest of the world to grow over the four years to 2023. Given other trends in the airline industry, the slight drop in aerospace exports this year could be explained by the fact that the sector does not only include aircraft but also satellites and surveillance equipment, all of which are growing globally.

The European car sector is going through a major transition after the diesel emissions scandals of recent years. Exports of vehicles based on the internal combustion engine are set to decline over the next four years across the board, with larger engines (greater than 2500cc) set to fall at an annualised rate of over 13%. Meanwhile, the electric car sector, although in its infancy, has grown since the first exports were recorded in 2017 to represent 8% of all European car exports in 2019. We see this trend accelerating, with growth set to be around 30% on an annualised basis by 2023. In effect, within the space of just four years, this segment of the sector will grow from making no contribution to automotive exports to accounting for nearly 11%.

Covid-19 has the capacity to drive innovation and technological change in Europe, and many car manufacturers across the region are using the time to accelerate an already emerging transition towards electric vehicles. This is very evident in the emerging data and although it is still too early to say whether or not the growth rates will materialise, it does suggest that Europe’s car sector is likely to adjust to the new reality of electric vehicles in the future.

GTR: How important is China as a trading partner with the EU and other trading partners in Europe like Russia and the UK?

Harding: It is hard to understate the importance of China as a trade partner with Europe generally, and the EU in particular. Excluding Russia, China has invested some US$411bn in Europe since 2005 and the UK was the recipient of around US$87bn of that investment.12

Meanwhile, China accounted for around US$260bn of Europe’s exports in 2019 and US$329bn of its imports. Germany is the largest individual exporter to China and exported around US$110bn in 2019, largely in the automotive sector, but also in machinery and components (engineering) as well as precision equipment and pharmaceuticals.

Russia’s trade relationship with China is somewhat different. It is overwhelmingly in oil and gas and was worth around US$59bn in total in 2019. In spite of the collapse of oil prices between 2014 and 2016, Russian exports have been growing since the Siberian gas pipeline became operational since 2019.13 Although the current price of oil has rendered that pipeline uncompetitive, largely because of the high cost of construction, the message that it sends to the US at a time of sanctions against Russia and trade tensions with China is clear: the two countries are prepared to create a strategic partnership in order to show unity against the challenges of the less multilateral undertone to global trade at present. This is a ‘marriage of convenience’ since Russia and China are very different and do not readily ally with one another. Nevertheless, both feel the pressures of their deteriorating relationship with the US and the UK. The pipeline is both a statement and, in China’s case, another mechanism for ensuring its energy security, a policy which has dominated its approach towards Eurasia and eastern Russia.

China is similarly important for the UK as its 10th-largest export partner, accounting for some US$21.1bn in 2019. The UK imports more than double the amount it exports to China at nearly US$50bn in 2019, and, as the UK begins the process of trading by itself outside of the framework of the EU from 2021, the role that China plays in its trade will be critical.14

For the UK, this is more than a trade relationship, however, and speaks to the strategic direction that the UK will want to follow now that it has left the EU. Its automotive exports to China were, between 2013 and 2015 at least, the flagship for buoyant UK exports at the leading edge of globalisation. Arguably, however, they more closely represented a phase of acceleration after the investment in the UK car sector by BMW in 2011. Since 2015, UK automotive exports have fallen back and the growing sectors in the country’s trade with China have been oil and gas, precious metals and works of art. The UK’s capacity to service China’s energy requirements given geographical proximity and the relatively small scale of its oil sector compared to, say, Russia, Angola or Saudi Arabia is, of course, limited. Meanwhile, trade in works of art and precious metals is volatile and does not suggest longer-term sustainability.

The UK is increasingly aligned with the US rather than the EU in terms of its approach to China. The EU will ultimately have to make an equivalent choice on use of Chinese technology and in terms of foreign policy if it is to conclude trade negotiations with the US post-Covid-19. The situation has been worsened by Covid-19: President Trump views China as the aggressor that should be held to account for its lack of transparency on the virus’ origins and has threatened more tariffs and sanctions as a result.

However, the UK is not like the US. It accounts for just 2.5% of world trade, and, come 2021, will not be aligned with any trading bloc. It is a military power, and contributes 2.14% of its GDP to Nato, in line with Nato guidelines. But can it afford to lose an average of almost US$5bn a year in inward investments from China since 2005 if it aligns with the US? Within this world of shifting spheres of influence, success will be driven as much by a capacity to bring economic weight to the table as it will to bring military weight.

GTR: How is the EU’s policy towards China likely to have to change to achieve an EU-US trade deal?

Harding: The EU’s multilateral approach to trade has been the embodiment of globalisation since the early 1990s. The single market, with its four freedoms of movement – capital, people, goods and services – is almost its definition. Importantly, however, a fifth “freedom” has become evident during the 30 years of globalisation that led to the GFC – that of the free movement of innovation, or the combination of technology and ideas. It is here that the US is feeling the strategic competition with China the greatest and it is in this space that Europe itself is increasingly categorising China as a “systemic competitor.”15

The EU27 as a single trade entity constitutes some 32% of world trade and is China’s largest trading partner. The discussion so far has clearly highlighted where much of this trade is taking place – in automotives, pharmaceuticals, aerospace and precision equipment – in other words, the traditional manufacturing sectors where Europe has known strengths.

The problem that both the EU and the US have is that China is increasingly operating in that space as well. This strategic approach has been the mantra of President Xi’s Made in China 2025 strategy and has resulted in rapid progression towards viable aerospace, automotive, pharmaceuticals and precision equipment sectors that compete directly with European businesses in their own markets. Ironically, the strategy was based on the tactic of Germany’s industrial strategy Industrie 4.0 and lays out similar approaches to creating growth in the digital economy through artificial intelligence, big data and the internet of things. Backed by undisclosed but large amounts of investment behind Chinese entities in European markets, alongside the more antagonistic approach taken by the US, the EU has had little choice but to modify its stance towards China.

That stance was first embodied in the 2016 EU-China 2020 strategy document which laid out the importance of a strategic relationship with China. Since the bulk of China’s investments in Europe were made in the first few years after the GFC, the intention was clearly to protect inward investment by Chinese companies while ensuring that Chinese export markets were open for European businesses.16

The consequence has been a substantial increase in services trade. For example, up to the end of 2017, the three-year annualised growth in exports of intellectual property (IP) licenses from the EU27 (excluding the UK) to China was nearly 44%. Since then, with the onset of tensions between the US and China, especially around IP, rolling three-year annualised growth in IP exports have fallen, albeit still standing at an annualised growth rate of 20% in 2019. In comparison financial services exports from Europe to China have grown by around 5% annually between 2016 and 2019.

The challenge now is that the EU27 is in the middle of a dangerous strategic stand-off between China and the US. Italy has signed up directly to the Belt and Road Initiative, even as France’s President Macron and Germany’s Chancellor Merkel were agreeing their combined, and more moderate, approach in 2019. Finding a collaborative approach to China across the 27 nations will be very difficult, particularly as Europe comes out of the Covid-19 crisis with more nationalism and protectionism that could threaten its overall unity.17

What has been clear for some time however is that the US is increasingly impatient with Europe. Its view of China’s threat to its hegemony, particularly in the financial and technological spheres of influence, has hardened in the run-up to the US presidential election and there is little sign that a Democratic president in Joe Biden will be materially different in his stance.

Trade relations between the US and the EU have been strained for some time, ever since President Trump ended any further dialogue on the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) when he came to power. At the level of goods, the issues are centred around the trade surplus that the EU has with the US – particularly in agriculture, automotives and general manufacturing. Small peace offerings on agriculture have been made, but there has been little progress since February 2020. Meanwhile, the European Court of Justice’s decision to limit the data transfer agreement between the EU and the US (and between the EU and the UK) has put further strain on relations and will have repercussions, not just for intelligence and security, but also for the development of data-related technologies outside of the EU.18

It is the security element that in the end may hold the key to a trade deal with the US, although this will have to be clarified after the US election. Joe Biden’s campaign literature suggests a slightly more emollient tone towards Europe (and Japan), but there is still a general frustration at Europe’s low contributions towards its own security in the form of payments to Nato. This has become explicit over the past two years since the G20 summit in Canada in 2018. If Germany in particular contributes its promised 2% of GDP to Nato, then there is potential to unlock discussions on both goods trade and, increasingly critically, digital trade as well.

GTR: Can the European export credit agencies (ECAs) compete with China in their domestic and export markets?

Harding: As has already been discussed, the strategic approach to China taken by the EU until recently has been to allow China to enter markets and invest in the mutual interests of multilateralism. As trade has become increasingly more nationalistic in its premise over the years since Brexit and the election of President Trump, individual European ECAs have discussed between themselves the role they can play in supporting European businesses in overseas markets against the backdrop of large-scale investments from China in Chinese businesses. Discussions with European ECAs over the past few years have suggested that this makes their role outside of Europe very difficult because they simply do not have the budgets to compete with the resources of their equivalents in China. Like their counterpart across the Atlantic, US Exim, they feel that they are in more than a competition – that trade has been weaponised.19

Covid-19 will make this challenge more acute. Discussions with practitioners over the lockdown period suggest that both public and private export credit insurers have become more risk averse and pulled back from some of the support that they had provided to more risky projects, for example in difficult jurisdictions or by smaller entities. The problem is that there is currently a greater risk of non-payment within the system due to the effects of the Covid-19 lockdowns, leaving government entities to pick up the tab.

It is here that the differences between China’s state capitalist approach and the free market approach will become most evident. Competition in domestic markets may be muted in the near term because of the broader consequences of the recovery from Covid-19. Put simply, when there isn’t much trade around, if exporting businesses can build within their home base to create a strong footing, they may gain a competitive advantage over overseas businesses. However, as the economy and global trade resume, the longevity of government support to exporters will become critical. As yet, there is little evidence that there will be a sizable response to the challenge.

GTR: How will Europe be affected by Brexit?

Harding: There is a common perception in the UK that the EU needs the UK’s market and supply chains as much as the UK needs the EU. This is what underpinned the brinkmanship that was a feature of the Brexit negotiations. The UK is the EU27’s second-largest export partner after the US, with trade values of around US$370.3bn in 2019. Since 60% of EU-UK trade is in just five sectors – automotives, pharmaceuticals, electrical products and equipment, machinery and components, and aerospace – there is certainly a high degree of dependency.

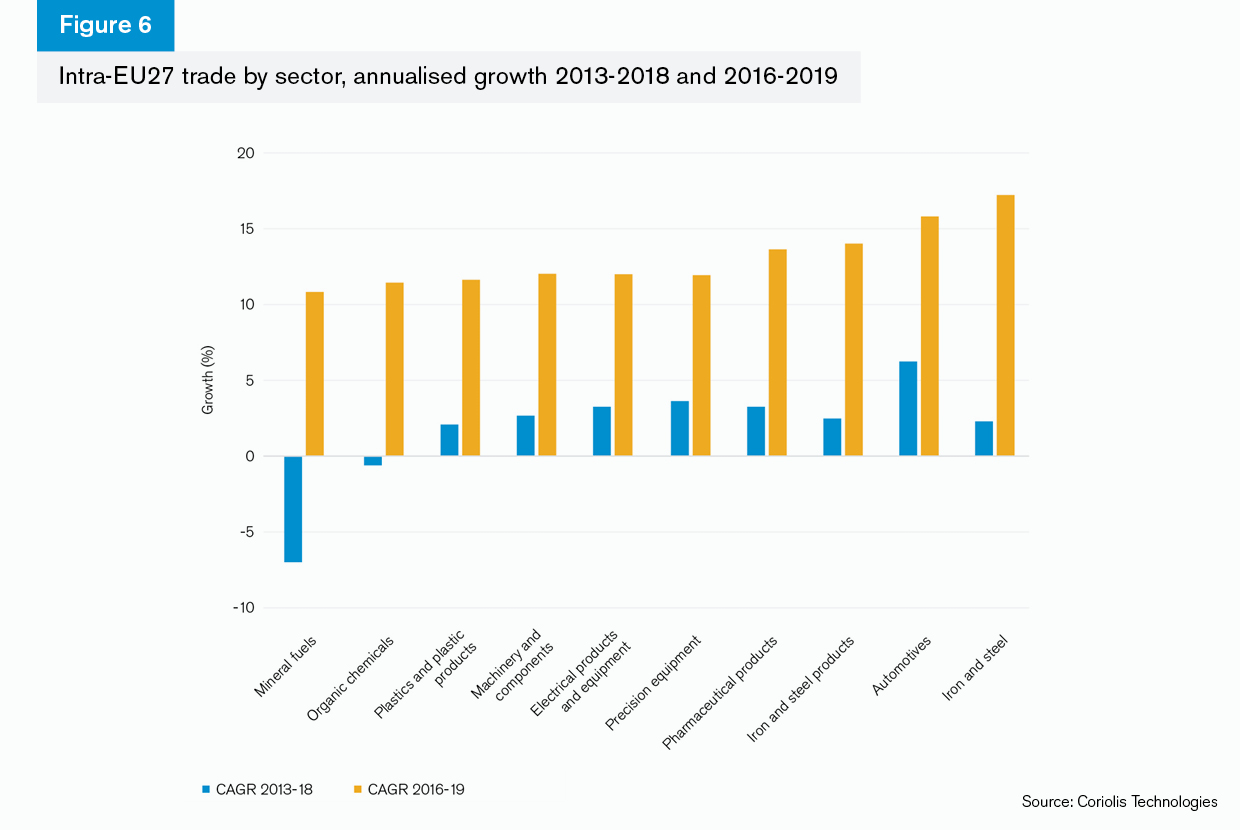

However, since 2016, when the UK’s decision to leave the EU was made, the relationship between the two sides has changed. In particular, the EU’s intra-regional trade had grown moderately between 2013 and 2018, but accelerated considerably across nearly all sectors between 2016 and 2019 (Figure 6).

Each of the top sectors for trade within the EU27 grew more rapidly on an annualised basis after 2016. For some, such as automotives, the rate of intra-regional trade growth roughly doubled; for others, such as pharmaceuticals, machinery and components and electrical products and equipment, the rate of growth nearly trebled.

Meanwhile, over the same period, the UK’s trade with Europe has grown by under 3%. This suggests that the more rapid growth in intra-EU trade was a result of a reshoring of supply chains from the UK to mitigate the risk of the UK’s exit without a deal.

Much of that growth was driven by increased oil and gas exports, which are set to fall back because of the drop in oil prices in 2020. Growth in automotive exports was negative, at -3.4%.

The conclusion is obvious – at 32% of the value of world trade, the EU has considerably more power, and greater scope to widen its supply chains across Europe without requiring the UK. The drop in automotive trade between the two parties is a warning sign: the EU’s automotive sector is restructuring around electric vehicles and moving away from diesel engines; the UK does not appear to be part of that process. It may be difficult, particularly in pharmaceuticals where the need for transnational co-operation at present is self-evident, but the EU can surely survive without the UK.

GTR: Which will be the biggest influence on UK trade – Covid-19 or Brexit?

Harding: The UK faces challenges that are the same as those for the whole world: how to exit from lockdown in a way that re-floats the economy without creating a wave of further infections that have an even greater impact on economic growth. These are well-documented challenges that will hinge on the government’s willingness to retain its support to employment and businesses, its financial commitment to rebuilding the economy sustainably in terms of social, environmental and transport infrastructure as well as its capacity, or indeed willingness, to continue to borrow at the current rate. At some point, there has to be a reduction in spending. This is unlikely to be because of the threat of near-term inflation and high interest rates, but rather because the government will naturally return to its small-state roots. This will raise the spectre of austerity again once Covid-19 is no longer the issue it is.

But it is fair to say that the UK also faces some unique pressures of its very own. It is an open economy and highly dependent on trade. During the financial crisis its exports fell back by 5% more than was the case for the rest of the world. Today, with a projected collapse of up to 32% in world trade, the UK should brace itself for the worst.

Trend forecasts would suggest that exports will pick up towards the end of 2020 and start to grow significantly into 2021. But this assumes, by definition, that the UK’s supply chain relationships and the costs of trade remain the same. This will not be the case unless a quick deal on trade can be reached with the EU. At present, this cannot be taken for granted howsoever much economic forecasting models may assume this smooth transition.

Trade will not be the same after the Covid-19 pandemic, of that we can be quite sure. We are already seeing greater distribution of inventories around the world to reduce reliance on single suppliers in a just-in-time inventory system. The role of China as the world’s factory will change as a result – there will be more sources of intermediate manufactured goods around the world so that supply chains do not grind to a halt. That said, while its role may change, its economic and technological influence will remain. This is one of the reasons why we cannot expect to see a reduction in the trade tensions between the US and China – if anything, trade will become more of a strategic game built on the quest for control over flows of finance and data. Expect the WTO to become weaker still as a result. Nations have already broken the principle of a level playing field in trade by increasing state aid and imposing export restrictions on medical and food supply chains. It will be hard for it to resume its authority after the pandemic.

Can the UK survive all this? It can if it recognises that its supply chains will change. The role of manufacturing in the UK economy may become less significant. Its allies, including the US and the EU, are engaged in the same, existential, strategic competition with China alongside a national battle for survival. The consequence could be that the UK may slip to the back of the queue for no other reason than that there are other strategic priorities. A lot will depend on how others behave.

That is the essence of where the UK is now: in a strategic competition between blocs of interest – Russian, Chinese, American and European – alongside weakening international governance. The behaviour of others matters because they will affect the UK’s plans, not just in terms of its economy but also in terms of its security. British exceptionalism in this landscape is not sustainable and the UK will need to think, and plan, for its post-Covid-19 place in the world against this backdrop of increased nationalism and shifting spheres of influence. Covid-19 should demonstrate how interdependent the world is; the UK should not be frightened now of re-affirming its commitment to multilateralism in trade and foreign policy if it is to keep its seat at the table.

- https://www.macmap.org/en/covid19; At the time of writing Bosnia had not changed its tariff rates during the crisis.

- https://www.wto.org/english/news_e/pres20_e/pr855_e.htm

- Source: Trading Economics

- Around 80% of the full data for 2019’s trade was available at the time of writing. Therefore, the method uses the Coriolis Technique for estimating to the full percentage given growth during the year as a base for 2019.

- Coriolis Technologies 2020: Trade Outlook 2020

- IMF World Economic Outlook, January 2020: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2020/01/20/weo-update-january2020. Subsequent outlooks have been significantly more negative

- https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-us-canada-53412598

- Harding, R. (2020): “On the Bright Side” Deutsche Bank, Flow Magazine, https://cib.db.com/insights-and-initiatives/flow/macro-and-markets/on-the-bright-side.htm

- https://www.cleanenergywire.org/factsheets/germanys-dependence-imported-fossil-fuels

- https://www.ft.com/content/ff3edd61-a404-48b0-adb8-65b91bc90486

- https://notesfrompoland.com/2020/05/21/poland-could-be-among-europes-biggest-beneficiaries-of-post-pandemic-production-shift-from-china-report/

- China global investment tracker dataset, accessed July 2020: https://www.aei.org/china-global-investment-tracker/

- https://www.scmp.com/comment/opinion/article/3050751/real-aim-gazproms-new-siberian-gas-pipeline-get-china-board-major

- Allen, B. and Chadha, J et al: “China and the United Kingdom – Economic Relationships” NIESR, 2020 https://www.niesr.ac.uk/sites/default/files/publications/NIESR%20Landscape%20Series%20-%20China%20and%20the%20United%20Kingdom%2C%20Economic%20Relationships_0.pdf

- https://carnegieendowment.org/2020/02/19/eu-and-china-in-2020-more-competition-ahead-pub-81096

- http://eeas.europa.eu/archives/docs/china/docs/eu-china_2020_strategic_agenda_en.pdf

- Harding, R. and Harding, J. (2019): Gaming Trade: Win-Win Strategies in the Digital Era London Publishing Partnership

- https://www.telecomtv.com/content/security/european-court-strikes-down-eu-us-electronic-data-transfer-agreement-39241/

- https://www.exim.gov/sites/default/files/reports/competitiveness_reports/2018/EXIM-Competitiveness-Report_June2018.pdf