Kenyan manufacturers have been rocked by months of global economic turmoil, with many struggling to deal with a perfect storm of high import costs and dwindling US dollar liquidity. But there is hope the new continent-wide trade area and the recent admission of the Democratic Republic of the Congo into the East African Community will offer some form of relief. Felix Thompson reports.

In Kenya, East Africa’s largest economy, there had been signs in the early months of 2022 that the manufacturing industry was ready to shake off the deleterious effects of the Covid-19 pandemic and return to growth.

The Stanbic Bank Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI), which offers an overall score on the performance of private companies in various sectors, registered a positive reading of 52.9 for Kenyan businesses in February, up from 47.6 the month before.

The PMI figure, which came in above the 50 threshold that signals expansion, was driven by a resurgence in consumer demand and a strengthening in new orders, with manufacturing and agriculture seeing the strongest output increase.

Any optimism was soon extinguished, however, by the economic blow dealt by the Ukraine war. Companies in the East African nation are now facing a range of problems, including disruption to the trade of key commodities, soaring import costs and dwindling access to finance.

The Kenya Association of Manufacturers (KAM) warned in May that its members were unable to obtain sufficient US dollars to buy raw materials from abroad, with a commodity price spike prompting a scramble for foreign currency.

By June, local media reported that a Kenyan producer of edible oils, Pwani Oil, had shut down a processing plant in the town of Kilifi, citing difficulties sourcing US dollars, which it needs to buy raw materials from suppliers overseas. That same month, Bloomberg reported that dollar issues were also hampering the operations of a competitor edible oils company, Kapa Oil.

“Dollar liquidity is strained,” says Mariam Shikanda, a treasury executive at Mabati Rolling Mills, a Kenya-based producer which buys steel from abroad, mostly Japan, before producing roofing sheets and other construction products.

“Most of our imports are dollar denominated, so we need US dollars to buy raw materials. We service about 30% of our needs through export collections, but then we need to go to the market and buy the other 70%,” she tells GTR.

Dollar demand has outstripped supply, experts say, so while a healthy amount of hard currency is flowing into the country via exports of tea, coffee and other goods, or through tourism and remittances, constraints are still being felt.

In the meantime, larger corporates are proving able to service their dollar requirements, at least partly, but the cost of doing so has shot up. Importers have been forced to pay well over KSh120 to the dollar, far above officially quoted rates.

“It is expensive getting dollars from banks,” says Shikanda. “You get different costs from different lenders, ranging from KSh121.60 [to the dollar], up to KSh124. With the lower end, the lender will provide about US$15,000 maximum, while KSh124 will get you around US$500,000.”

Financial institutions are working to help import clients secure the dollars they require, but multiple banks have told GTR the Kenyan market is overstretched and they are having to think carefully about who they lend to.

“The escalation of commodities prices has really impacted our trade business, particularly oil, wheat and palm oil, and steel as well,” says Timothy Mulongo, senior business development manager at KCB Bank Group.

“We do not have enough foreign currency to meet demand from our customers, so we have to prioritise and allocate what is available. We are trying our level best just to ensure that we have sufficient foreign currency to take care of our clients – particularly, clients that we have funded, or provided trade solutions to,” he tells GTR.

New bank solutions

In the wake of these problems, international lenders operating in Kenya say they are evaluating new solutions to help domestic importers – as well as the wider trade finance market – manage booming costs and currency issues.

“From a US dollar requirement perspective, what we’re trying to do is just look at off-balance sheet solutions or things like letter of credit (LC) issuances,” says Carol Kihuna, vice-president, treasury and trade solutions at Citi in Nairobi.

“For someone who is looking at trade loans, rather than make that advance payment right out the gate, we look to offer an off-balance sheet item. Then we are able to bring in the goods, but with no cash outlay at the very beginning.”

She tells GTR that Citi is using swap instruments to boost foreign currency, but the “forwards market is not what it used to be” and is “quite tight”. She says the bank is also looking to boost liquidity through structured LCs.

Nonetheless, local Kenyan banks that serve smaller corporates and small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), warn they are being shunned by larger financial institutions that in the past funnelled hard currency down the chain.

“The big banks have kept their dollars for their customers, and they are the main suppliers of foreign currency in this market,” says Eunice Monzi, a trade finance specialist at Victoria Commercial Bank.

“The tier-two and tier-three banks are struggling. Unless a development bank comes and finances that gap, I do not see the market working in the short term, because we are becoming very limited for dollars ourselves,” she tells GTR.

Manufacturers make up a large chunk of Victoria Commercial Bank’s business, with the lender helping firms finance the import of raw materials and inputs from major markets, such as India, China or Europe.

“We tend to find our correspondent banks, even the local financial institutions we relate with, have caps on how much they can give us,” Monzi says, adding the amounts are generally very small. “We cannot even service our clients.”

Even before the start of Russia’s war in Ukraine, local trade finance lenders across East Africa were struggling, with a May report from the African Development Bank (AfDB) showing the trade finance gap in Kenya and Tanzania stands at about US$3bn and US$1.3bn respectively.

The analysis was based on data collected from over 800 companies and nearly 60 banks in both East African countries between 2012 and 2020, and reveals that trade finance application rejection rates remain troublingly high.

On average, 17% of applications in Tanzania and 20% in Kenya were turned down by financial institutions between 2018 and 2020, for reasons including insufficient collateral, weak creditworthiness and hard currency shortages.

About a quarter of exporters in Kenya and 20% in Tanzania fail to meet some export sales due to a lack of access to trade finance each year, it says. “We estimate the average value of lost trade due to unmet trade finance demand at US$80,107 and US$24,966 a year per firm in Kenya and Tanzania, respectively,” the report reads.

No supply crunch, yet

While companies are clamouring for US dollars to manage surging import costs, the Central Bank of Kenya and the National Treasury have dismissed concerns, arguing there is sufficient foreign currency.

As reported by Bloomberg, central bank governor Patrick Njoroge said in May that Kenya’s foreign exchange market generates and distributes about US$2bn a month, which is enough to meet all demand in the economy.

According to the same news agency, National Treasury permanent secretary Julius Muia said in June that some manufacturers were buying more dollars than they need and therefore creating an “artificial shortage”.

Experts say Kenya’s neighbours are also feeling the crunch – much of which has been driven by Russia’s war in Ukraine.

Daniel van Dalen, a senior country risk analyst at advisory firm Signal Risk, tells GTR that Burundi is “really battling” higher commodity prices, given it has lacked foreign currency reserves for years. “They are having supply chain issues for fuel and importers cannot buy food. You are seeing country-wide shortages that have persisted since March.”

Malawi, too, faces similar problems.

“There is a possibility for dollar shortages for them in the medium term if they don’t get their ducks in a row and make sure they can afford fuel imports. They are trying to navigate an IMF deal, but a lot of it comes down to structural reforms.”

Signal Risk’s van Dalen believes Kenya and Tanzania are unlikely to face major supply issues in the next few months, given that while current account pressures are growing, their economies are “more resilient” and there are sufficient forex reserves for fuel and food.

Kenya is sitting on forex reserves of around US$7.95bn and Tanzania’s stand at around US$5.1bn, he notes, adding that both countries have nearly five months’ worth of import cover, which is the threshold set by the East African Community (EAC).

But he says input prices are “going to rack up”, and Kenyan manufacturers and consumers will “feel the crunch” from bumper energy and commodity costs this year.

Building on regional opportunities

In the longer term, there are hopes regional and continent-wide trade agreements will help kick-start growth in manufacturing across East Africa’s largest economies, including Kenya, despite more immediate headwinds.

The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), which came into force in early 2021, aims to significantly boost intra-regional trade levels, which to date remain dismally low. Investors are increasingly eyeing up the benefits of an agreement that seeks to cut tariffs on up to 90% of goods produced on the continent.

As reported by Nikkei Asia in July, Japanese auto company Mitsubishi said it would begin producing vehicles in Africa after a 10-year hiatus, selecting Kenya as the location for its renewed manufacturing push.

The Associated Vehicle Assemblers (AVA), a Kenya-based manufacturing entity which produces vehicles on behalf of other automakers, has won the contract to assemble the new cars and will use knocked-down parts imported from Mitsubishi’s plant in Thailand.

According to the Nikkei report, the Japanese firm’s decision was partly driven by a desire to capitalise on the AfCFTA and, while the initial plan is to sell to the Kenyan market, the ultimate goal is to export to buyers elsewhere in Africa.

Banks and companies are also contemplating opportunities related to Democratic Republic of the Congo joining the EAC, with the country having been ratified as the seventh member of the regional intergovernmental organisation in July.

The agreement brings a wealth of benefits to DRC’s population of roughly 90 million people, who will now be able to enter visa-free when travelling to fellow EAC countries: Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Burundi, South Sudan and Rwanda.

Import taxes on DRC-made goods will also be slashed or removed, while Congolese companies should eventually face fewer administrative barriers when exporting into other EAC countries, meaning faster clearance of goods.

The deal offers DRC better access to the Indian Ocean ports of Dar es Salaam and Mombasa, and theoretically will allow EAC countries to move goods cheaply across the breadth of Africa and ship from the Atlantic coast. Earlier this year, DRC started construction of a US$1.2bn deep-water port that is slated to be completed by 2025.

“In the longer term, it’s a very interesting move, because it effectively connects one side of Africa to the other,” says Signal Risk’s van Dalen. “You are seeing Uganda going in and saying we need to build roads; Tanzania has a lot of port infrastructure development… There are plans to link Mozambique, Tanzania, DRC and Angola.”

Mulongo at KCB says the bank has seen “a lot of interest” from Kenyan investors and customers in the manufacturing and extractive industries looking to establish themselves in the DRC. “In the next couple of years, we should see a flurry of activity,” he adds.

But security risks remain a major factor in the Central African country and could hinder attempts to bolster trade between the DRC and its EAC neighbours.

Many of the roads used to ferry goods into the DRC run through areas rife with violence.

“For manufacturers in those countries, it’s always difficult to count on those trade routes. As recently as July, a key route connecting DRC to Uganda and Kenya got shut for a week because a lot of armed banditry was taking place in DRC,” says van Dalen.

Broadly, there is a general lack of trade infrastructure in DRC, such as roads or rail routes, which Kenyan manufacturers fear could ultimately stymie efforts to capitalise on both the newly expanded EAC, as well as the AfCFTA.

Tobias Alando, KAM’s acting chief executive, said during a webinar in August that the AfCFTA could well help Kenyan manufacturers diversify into non-traditional export markets, such as West and North Africa – and grow jobs in the country.

But he flagged various challenges both within, and outside of, Kenya. He urged the Kenyan government to create a conducive business environment, citing currently high taxes, regulatory overreach, logistics costs and trade barriers.

“The transport and logistics system is undeveloped across the continent, with some countries having almost no roads, air or rail systems,” he said, specifically pointing to DRC. “Accessing that market, in terms of infrastructure, is a challenge.”

In numbers: Kenya’s manufacturing woes

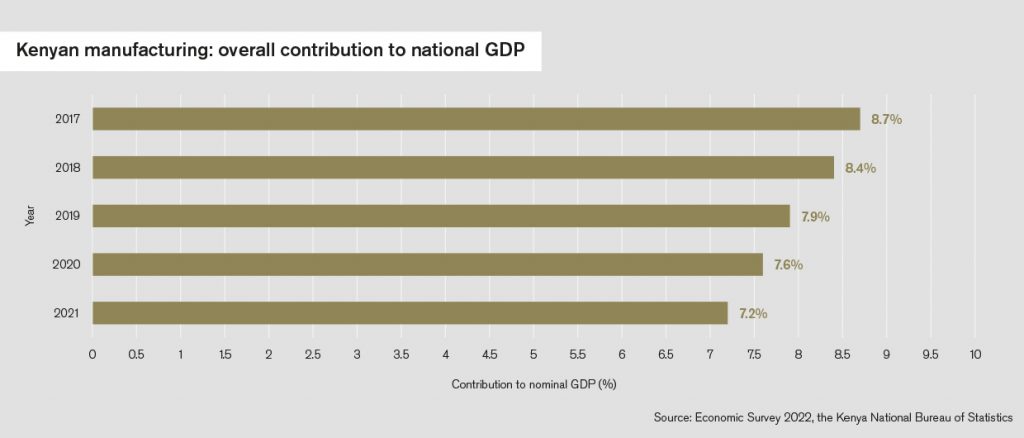

The Kenyan government had high hopes for its manufacturing sector in 2016 when it launched its ‘Big Four’ agenda, a blueprint which laid out plans for strengthening the country’s economy, food security, housing and healthcare sectors.

Key to this plan was a target to boost the manufacturing industry’s contribution to GDP from around 9% to 15% by the year 2022. But with the deadline having now passed, the East African nation has fallen well short of the mark.

Even before the Covid-19 pandemic battered African manufacturers and forced many to shutter factories and slash jobs, the Kenyan government’s lofty goal had already been slipping ever further out of reach.

As detailed in an April report from Deloitte, the sector’s share of GDP has progressively declined in recent years and fell to 7.6% in 2020, a plunge that can be attributed to a drop in the number of food products being produced locally and competition from cheap imports.

Covid-19 worsened the situation, with the pandemic and related restrictions leading to a significant contraction of the manufacturing sector’s output by 3.9% in the second quarter and 3.2% in the third quarter of 2020, Deloitte says.

According to World Bank data, the manufacturing sector’s contribution to GDP in Kenya has since dropped further, to 7.2% in 2021.