The textiles industry is notoriously fickle, volatile and hard to predict. Companies and financiers need to be able react quickly if they’re to survive. Finbarr Bermingham reports on the efforts of two countries trying to improve their industries.

Every industry that is dependent on commodities can expect to have its ups and downs. With its reliance on everything from cotton to silk, wool to nylon, leather to viscose, the textiles market is exposed to more than one. And commodity exposure is just one consideration for those in the fabric game. Given the fickle nature of fashion trends, a textile that sells well one season can find itself obsolete the next. People are also arguably more conscious about the source of the clothes they wear than the food they eat or the fuel they burn. Social and ethical considerations and, thus, reputational risks are more amplified in the textiles trade than almost any other.

In April of this year, the eight-storey Rana Plaza garment factory complex collapsed in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Images of limbs protruding from rubble and dust-caked bodies being hauled free of debris haunted social media, shocking all who saw them. It was a very human tragedy, causing 1,129 deaths and more than 2,500 injuries. And, as the deadliest accidental structural failure in modern human history, it was one that stemmed from manmade errors: negligence and poor regulation.

It sparked an outpouring of soul-searching among western consumers. Companies who had sourced or were suspected of sourcing stock from suppliers based in the Rana Plaza complex were named and shamed (including the UK’s Primark, Italy’s Benetton and American apparel provider Children’s Place). It also emerged that in 2011, Wal-Mart, H&M, and the Gap were among the companies that refused to sign an agreement that would “establish an independent inspectorate to oversee all factories in Bangladesh, with powers to shut down unsafe facilities as part of a legally binding contract signed by suppliers, customers and unions”. Many consumers vowed to boycott the brands indefinitely, or at least until they revised their policies in Bangladesh.

Incidents such as Rana Plaza and the ‘sweatshop’ scandals that plagued the likes of Nike in the 1990s highlight the precarious business of textiles supply chains: nobody wants to be seen to be wearing a garment that was unethically sourced or manufactured. It has placed Bangladesh’s textile industry in a precarious position and by virtue of this, its economy too.

Rags to riches

In 2012, the textiles industry provided employment for 45% of Bangladesh’s 72 million-strong workforce. It accounts for 13% of GDP and 75% of total exports. The industry is growing at 12% a year on average and many international retailers, particularly those in the value sector, have been sourcing from the country since the 1980s. It is the third-largest exporter of apparel products to Europe and fourth to the US. A 2011 study by consultancy firm McKinsey found that 89% of chief purchasing officers named Bangladesh as a “top three sourcing country hot spot in the next five years”.

Edward Faber is a relationship manager at the Asian Development Bank (ADB) covering Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Indonesia, Pakistan and the Philippines. Speaking to GTR shortly after returning from a trip to Bangladesh, he suggests that the real problem with monitoring safety conditions in factories is down to subcontracting. “A big buyer will have a contract with a certain factory, which could then subcontract and the ultimate buyer won’t know about that. Once it’s subcontracted, the standards may not be as high as the buyer would expect.” Faber says that on his visits to Dhaka, he’s seen nothing that he’d consider to be sub-par in terms of safety. But with the eyes of the world now trained on Bangladesh, strict governance and monitoring is essential.

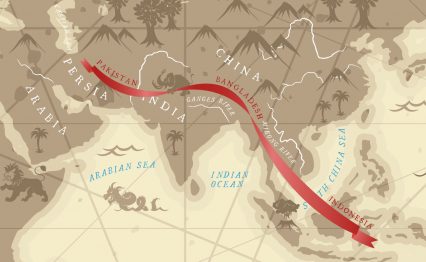

Bangladesh’s textiles growth spurt can be partly attributed to a change in the Chinese market. China is still the largest exporter of textiles in the world – in 2010, it accounted for 40% of readymade garment imports to the US and Europe. In his book Tiger Head, Snake Tails, Jonathan Fenby writes of the historic city of Shaoxing, which “houses more than 40,000 textile-exporting companies operating in a main market with a floor area of 600,000 square metres”. But as China’s economy develops, many workers are seeking the next level of employment, away from crowded textiles factories. Wages are rising too, meaning the cost per unit in China is higher than it has ever been before. Buyers are seeking new and cheaper markets.

The unit cost in Bangladesh is extremely low and the people have a long history of textiles manufacturing. “Bangladeshis are very skilled in this area,” explains Faber. “They’re very dextrous and the cost of labour continues to be very low. The population is so large and for the most part, underdeveloped. In Dhaka you still see people trying to ferry you around on rickshaws, which you don’t see in Manila or Karachi. You really feel that Bangladesh is a few stages behind in its development compared to many other countries – their cost of labour will continue to be one of the lowest.”

As befits the national exports portfolio, Bangladeshi commercial banks are heavily exposed to the textiles sector – sometimes 30% of their entire credit lines go to the industry. The ADB too is very active. “Primarily we’re providing guarantees for letters of credit (LCs) issued by the local banks,” Faber says. “We’re seeing a lot of import of capital machinery for spinning mills, cotton to be made into thread in the mills and fabrics from China. The machinery comes from parts of the EU and you see a lot of cotton from West Africa, Ukraine, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Zambia, Greece and Australia, as well as accessories from Singapore. We’re supporting these imports with the idea that they then get turned into exports.”

The ADB’s guarantees are particularly important when you consider that Bangladeshi companies are top of the International Cotton Association’s (ICA) list of those that fail to make payments to suppliers. The ICA lists 93 defaulting firms, compared with 89 in India and 50 in Pakistan. There has also been a big increase in the number of non-performing loans in Bangladesh, which Faber puts down to the volatility of commodity prices. “Companies engaged with commodities lenders don’t do any hedging,” he explains. “It’s not permitted for starters, but if it was I doubt they’d know how.”

Quite often, Bangladeshi spinning mills will decide to import a lot of cotton when the price is high as it drives up the price of the subsequent yarn. However, if prices fall when it’s sitting in their inventory, then that will be borne out in the market rate for yarn, meaning they’re running a loss. It’s a common issue in countries which are reliant on the import of raw commodities.

Spinning a yarn

1,600 miles across Indian territory, Pakistan has the luxury of not having to deal with this issue. In 2012, the country produced 13.6 million bales of cotton, a year-on-year increase of 18.6% and theoretically, enough to supply its textiles business. Like Bangladesh, Pakistani textiles are crucial to maintaining economic health. It employs around 30% of the workforce (second only to agriculture) and contributes 9.5% of GDP.

The country is currently experiencing a boom in its denim exports, mostly because the fabric finds itself in vogue in the western world. Naveena Exports, for instance, is a supplier to Levi Strauss and recently utilised a US$30mn export refinancing package from Habib Bank Ltd (HBL) to fulfil its orders. Gul Ahmed, a manufacturer of finished garments, supplies US department store Macy’s and provides bed linen products to some of the world’s top hotels, including the Weston and Starwood groups.

Pakistan’s industry is further along the line than Bangladesh’s. It produces higher-end products and its banking system is more mature. “The CEOs of companies know how to manage their inventories,” Saad Abdul Aziz, a senior relationship manager in HBL’s corporate and investment banking group tells GTR. “They know when to invest and procure. There was a cotton pricing issue in 2011 and after this, they’ve been very careful in stocking up to meet orders. The variability is essential for companies. We provide them with cotton hedging opportunities, where we lock in cotton rates, which stabilises their streams.”

But Pakistan’s attempts to move towards a more value added economy have been affected by the policy actions of a neighbour to the north: China. In 2011, the PRC embarked on a hedging mission of its own when it began purchasing cotton from its own farmers at premium prices in order to keep the rural market afloat. As of June 2013, it had bought some 10 million tonnes of raw cotton at above-market prices, keeping domestic cotton prices up to 40% higher than the global benchmark. It’s thought that at one point, the government held around 60% of the world’s cotton in reserve.

The initiative has attracted the scorn of cotton traders and textiles companies which have accused China of distorting prices. “The longer China holds on to its policy, the worse and direr the situation will become,” Joe Nicosia, global head of cotton at Louis Dreyfus Commodities told Reuters earlier this year. It’s been criticised in Pakistan too, where it’s had a negative effect on the exports portfolio.

“In 2012, cotton yarn exports increased by 100%,” says Aziz. “But we would prefer to export value-added goods. In the same financial year, textiles exports fell by 51% and bedware by 7.1%, all because there’s more cotton being exported. The spinning industry has benefitted, but it’s a low margin commodity and you can’t thrive on the export.”

Local companies are finding it more difficult to access affordable yarn for manufacture, since so much is leaving the country. At the moment, the new Pakistani government isn’t in a position to counteract the trend. Foreign currency reserves are low in the country and the exports to China are a good way of adding to the coffers. But it’s been mooted that in the medium-term, the new textiles minister Maqbool Rahimtoola will place a levy on the export of yarn – or even ban it outright. Sanctions such as these would enable Pakistan’s manufacturers to purchase the yarn at a fair price, as opposed to it being exported for relative pittance.

In Istanbul this year, GTR listened to Turkish businesspeople talk about the government’s efforts to graduate the economy to full value add status. “I love the strategy to reduce their import dependency,” Cihat Takunyaci, BNY Mellon’s country manager in Turkey said at the time. “It’s important to stop importing things that don’t create value add.” He mentioned the import of thread to cheap make t-shirts, urging Turkish vendors to source and create internally (Turkey is the eighth biggest cotton producer in the world).

Turkey’s economy is light years ahead of Pakistan’s, which in turn, is significantly larger than that of Bangladesh. But these nations all find themselves at differing points on the textiles lifecycle. Graduation to value add status brings higher wages and better-trained workforces – clear indicators of economic and social development. Once they’ve gone up a notch, there will be less-developed countries (perhaps in East Asia or West Africa) to take their place.

It’s something to strive for and HBL’s Aziz is confident that Pakistan will get there soon. “The investment in the textiles industry shows that it could happen,” he says. “The 20 largest companies have vertically integrated – they have control over the entire chain. Companies right now are putting US$10mn into capital expenditure. Living off yarn is futile. Over the next five to 10 years you’ll see a change in direction. The new government is more industrial and has a large investment policy. There’s a clear path outlined.”